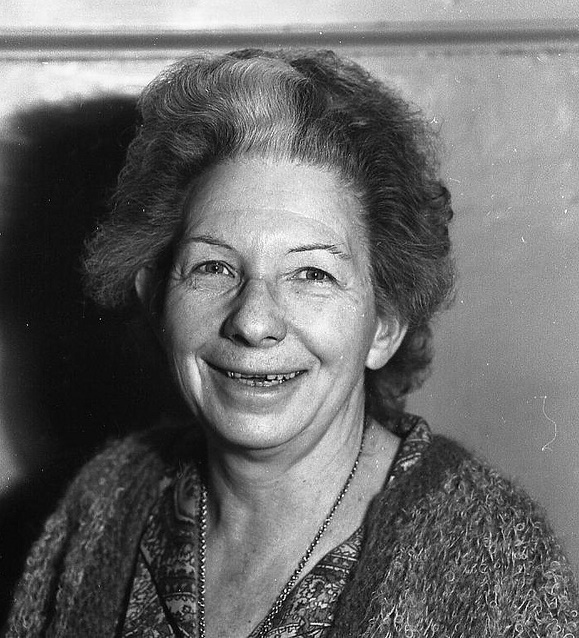

Edith Roller was my great-aunt, the sister of my maternal grandmother. She died in Jonestown shortly after I turned seven, and I never met her. But my mother remembered Edith and occasionally talked about her when I was growing up. As Edith’s journals seem to have become a significant source of information about what occurred in Peoples Temple and at Jonestown in the years before the tragedy, some of the family lore about Edith, particularly about her work as a covert agent for the CIA, might be of interest to Jonestown researchers.

Edith Roller was my great-aunt, the sister of my maternal grandmother. She died in Jonestown shortly after I turned seven, and I never met her. But my mother remembered Edith and occasionally talked about her when I was growing up. As Edith’s journals seem to have become a significant source of information about what occurred in Peoples Temple and at Jonestown in the years before the tragedy, some of the family lore about Edith, particularly about her work as a covert agent for the CIA, might be of interest to Jonestown researchers.

Stories about Edith’s connections to U.S. intelligence agencies circulated both before and after the deaths – Jim Jones teased her from the pulpit about her association with the CIA – but they aren’t mentioned in her online biographical sketches. This is understandable. Because Edith’s work was covert, it is by its nature difficult to document to the standards required by historians.

I’m afraid that I cannot produce hard evidence that Edith worked for the CIA, but I have very little doubt that she was so employed for a number of years. It was taken as a given by the family. It is perhaps worth noting that my mother’s family were not naifs when it came to the secretive side of Cold War Washington. My maternal grandfather – Edith’s brother-in-law, Duncan Clark – was Director of the Division of Public Information for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission at a time when its work was sensitive. Duncan was well-versed in secrecy, despite his rather Orwellian title, and would not have been easily deceived by a fabulist.

I am not completely sure how Edith became connected to the CIA, but I believe she worked for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II. The CIA was established as the successor agency to the OSS a year or two after the war ended, and a lot of OSS people came over, Edith likely among them.

Edith was given a cover job and sent overseas, where she remained for many years, first in India and then in Cyprus. At one point her ostensible job was with the UN High Commission on Refugees. She returned to Washington at least once in the 1950s and once in the 1960s, and worked at Langley on both occasions.

I think that Edith left the CIA before she worked for Bechtel. That job was something of a severance package, I imagine. Why she left is a mystery, but I think she had come to have fundamental political differences with the agency. My mother passed away a few years ago, so I can’t ask her for details, but she told me that Edith had not been entirely loyal to the agency, and had been passing information in both directions in Cyprus. “Double-agent” was the term my mother used, but she had a flair for the dramatic.

There were other reasons, though, for thinking that Edith’s disenchantment was likely longstanding. When she was in India, she was involved in an automobile accident. Another passenger in the car was a married government official with whom Edith was having an affair. The agency was not happy about this, and it remained a black mark on her record.

I don’t think Edith’s work for the CIA was terribly sensitive. If I had to guess, I’d say that the CIA noticed that she had a talent for observation and for writing down her observations. It was a talent she later pursued during her years in Peoples Temple in producing hundreds of pages of diary entries. So I suspect that they sent her places to observe and report. I consider it a rather amusing twist that Edith apparently once became rather angry with the agency for refusing to give her access to a report that she herself had written because she did not have sufficient clearance to view it.

There is a suggestive quote of Edith’s that I have at third hand. After President John Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Edith indicated that she thought it was a CIA job that had not gone well. “Assassins,” she said, “are just not reliable people,” suggesting that she had known a few. Make of that what you will.

What I’ve written above is grounded in fact, even if not documented to a historian’s standards. How relevant it is to Edith’s involvement with Peoples Temple is an open question.

My mother wondered if Edith’s involvement with the Temple might not have been professional. I don’t think that was the case. I think Edith was sincere in her devotion to Jim Jones. I have been told that Edith fell in love twice, once with the Indian official, and once with Jones.

My mother was fond of Edith, and I think she would have preferred to believe that Edith was not really one of Jones’ adherents, but her diaries indicate there is much reason to believe that she was. My mother did say that Edith’s last letters to the family were uncharacteristic, and that she thought they might have been a way of signaling that she was being held against her will. But my mother had reasons to want to think that after the deaths in Jonestown, and those letters no longer exist. Again, make of that what you will.

One question that still remains a mystery is how Edith first came into contact with the Temple. Did that start out as a work assignment? If so, did she abandon that assignment or – conversely – did she continue to work undercover? Certainly the record that she left behind – the diary that she didn’t expect to become public – does not suggest that be the case, and I have no good reason to believe that she was anything than she seemed to be: a loyal member of Peoples Temple who emigrated to Guyana with 900 other members in the group and who died with everyone else.