Setting the Stage

In one sense, the significance of the fortieth anniversary of the deaths in Jonestown – or of any other event – is arbitrary. None of the central facts of the Peoples Temple story changes as we pass from one anniversary to the next. That said, as a literary scholar, I do understand and believe in the symbolic power of something like a fortieth anniversary in bolstering the narrative structure of history, that story that we are always forgetting we are telling.

With this in mind, I want to consider the ways in which the Jonestown story is very much a part of a larger American psycho-drama. Normally, the story is offered as a strange, outlying event, as the tale of a cult, led off into the wilderness by a madman and into the abyss. The ethics of this version of the story place the blame on those who have gone on and are by virtue of their deaths unable to present the subtleties of their experiences. Peoples Temple and Jonestown are American stories, as American as apple pie, pilgrims and astronauts dancing on the moon. All of these things come from our shared traits, our American fantasies and personalities that tend always toward the sentimental and the extreme. The example offered to us by those who died in Guyana on November 18, 1978 proves the point, but no more than the image we have of pilgrims landing on Plymouth Rock or of Armstrong and Aldrin dancing on the moon.

In what follows, I would like to explore the uses of traditional narrative structure that we typically associate with the arts on our own sense of history and politics. I will insist on the distinctions that I see operating at the heart of American culture. The most central of these characteristics will be its tendency toward extremism, its utter sentimentality and its attraction to personality.

Jonestown does not tell the story of a cult living on the margins of society. It is one of many American dramas centered around the cult of personality.

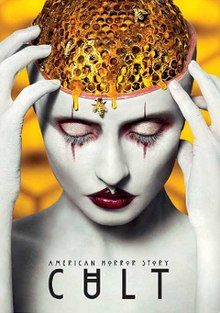

American Horror Story

Ryan Murphy’s television series, American Horror Story (FX Networks), is about to enter its eighth season, which is entitled Apocalypse (2018). As followers of the series have come to expect, little is known at the moment about the plot or direction of this season. Murphy will probably draw on his cavalcade of actors from past seasons to populate Apocalypse, which will be, in equal parts, distinct from and bound up in plot lines from seasons one through seven. In other words, viewers will be offered an entirely new plot line in Apocalypse that, if it is anything like other seasons, will allow for moments of intertextual dialogue with past seasons. With that in mind, I will be especially interested to see how the social and political commentary offered by this particular doomsday narrative relates to and deepens the conceptual work of season seven, Cult (2017).

Ryan Murphy’s television series, American Horror Story (FX Networks), is about to enter its eighth season, which is entitled Apocalypse (2018). As followers of the series have come to expect, little is known at the moment about the plot or direction of this season. Murphy will probably draw on his cavalcade of actors from past seasons to populate Apocalypse, which will be, in equal parts, distinct from and bound up in plot lines from seasons one through seven. In other words, viewers will be offered an entirely new plot line in Apocalypse that, if it is anything like other seasons, will allow for moments of intertextual dialogue with past seasons. With that in mind, I will be especially interested to see how the social and political commentary offered by this particular doomsday narrative relates to and deepens the conceptual work of season seven, Cult (2017).

These two ideas – cult and apocalypse – are obviously related to one another in several ways. Leaving aside the role of religious doctrine and sentiment that govern these distinct but complementary forces, it would be difficult not to acknowledge the somewhat over-determined Americanness of this conceptual pairing. Americans are a sentimental people who are historically susceptible to the manipulation of their feelings. We are given to extremes (and to extremism, that character trait that we might perhaps say was invented on our own shores) and this fact has made it easy for us to find ourselves, over time, swayed by larger-than-life figures who know just how to appeal to our sentiments.

AHS: Cult provides its own historical narrative of this very American phenomenon. Mixing realism with grotesque fantasy, this last season of the show began with the inauguration of Donald Trump and, more specifically, the extreme reactions (for and against) this phenomenon that, to American readers, will be all too familiar. Characters in the AHS world take their reactions to their logical limits, offering viewers a way to imagine what the world would be like if every voter acted out his or her worst political fantasies onto his or her imagined political enemies. The world of politics – and of the political marketplace of sentiment that is at the heart of American electoral rituals – is presented to AHS audience members as made up of cult members, blindly and energetically working to ensure their own demise. No wonder Americans have, in the course of our brief history, succumbed to so many Apocalypse panics. The election of Donald Trump seems to have set the stage for our recurring end-of-days nightmare, or so the writers of American Horror Storywould have us believe.

Over the course of the Cult narrative, we are offered a fascinating array of charmers and cult leaders. Some are obvious: Charles Manson, Marshall Applewhite, David Koresh, Jim Jones. But there are others.

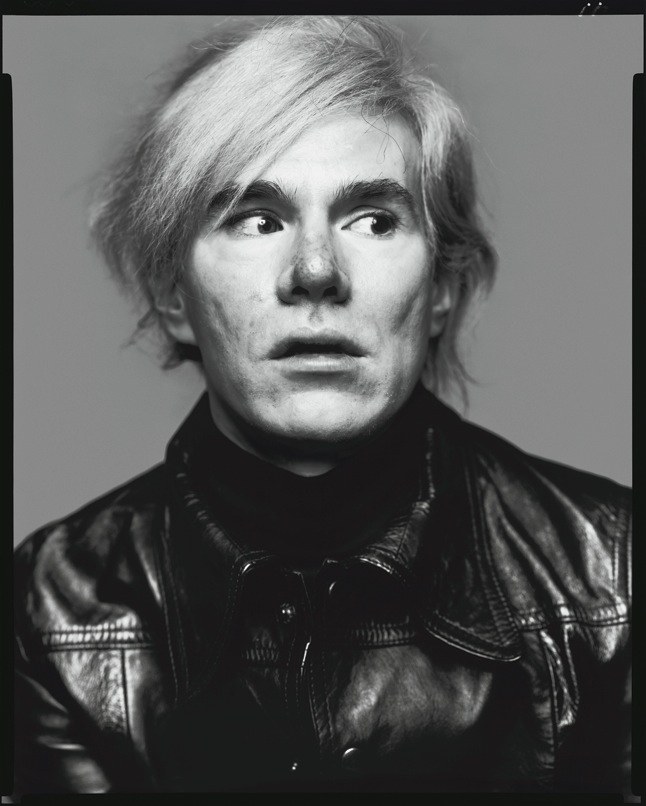

One of those anomalous examples is Andy Warhol. But let us consider AHS’ choice for a moment. Warhol, of course, was the center of a kind of cult (The Factory) and certainly can be praised (or blamed) for contributing to the almost theological significance of personality in American culture. Without knowing it, Warhol’s jokes – about superstars, fifteen minutes of fame in the future, celebrity for the sake of celebrity – have come true, and it could be argued that we are, for better or worse, living his fantasies out to their logical extremes.

One of those anomalous examples is Andy Warhol. But let us consider AHS’ choice for a moment. Warhol, of course, was the center of a kind of cult (The Factory) and certainly can be praised (or blamed) for contributing to the almost theological significance of personality in American culture. Without knowing it, Warhol’s jokes – about superstars, fifteen minutes of fame in the future, celebrity for the sake of celebrity – have come true, and it could be argued that we are, for better or worse, living his fantasies out to their logical extremes.

Like Reverend Jones, Warhol was the emotional center of his own universe, which revolved in both instances around these men. Warhol may have lacked Jones’ charisma and energy, but both figures understood how to transform themselves into something larger. For Jones, this meant overcoming the facts of his life and identity by creating a fictional self. It was not enough for him to be who he was. In order for him to create a religious following, he needed first to create a mythology, one that was tied directly to his own sense of power and divinity. In other words, Jones’ ability to sell himself as faith-healer required him to invent another version of himself that allowed him to be more than who he already was.

So many people look back at members of his congregations, at his followers, and ask how they could be fooled, why they didn’t see through the charade. But what about Jones? Common wisdom tells us, in hindsight, that he was a master manipulator, that he understood that he was hoodwinking people, fooling them into believing in his divinity. In spite of this, I would like to suggest that we look at Jones as the first person to fall into his own trap, to become charmed by and believe in his own myth.

After all, a cult of personality can operate only if it centers its attention around a clearly designated figure whose affection is totally desired by all in its orbit. One way to characterize this central figure is as the bamboozler, snake oil salesman, master manipulator, etc. This kind of thinking is useful enough and easy to understand, especially from afar and in hindsight. In this case, the cult leader is the villain, the source of pain and control; the members, on the other hand, are the victims. The cult itself is the structure enabling this interaction.

But what if we look at the center of the cult of personality – the “cult leader” – as the first person to fall into the trap? It’s too easy, in the end, to think about cults of personality as governed primarily by the needs of villainous leaders who want nothing less than control over us all. The real problem, and power, of structures of cult sentiment is in the primacy of the leader’s belief in himself or herself. Jones (like Koresh, Manson, Applewhite, etc.) was the first person to believe in his divinity. In lying to others (about – you name it – his background, healing powers, race, sexual powers, and so many more), Jones also lied to himself. His control over others allowed him to believe that what he was saying was true. Trickery was always a means to an end for Jones, but, as time went on, it is hard not to see him as his own most enthusiastic and devout follower. He was the first, and last, to believe in his own supremacy. This is perhaps what is most troubling about the example of Jim Jones and his own self-fulfilling cult of personality.

Of course, talking about Jones as the central figure in a “cult of personality” is perhaps less loaded than it would be to apply more familiar terms to him simply as a “cult leader.” Even though these two descriptors are neither mutually exclusive nor perhaps even at odds with one another, it is important to understand the differences between these lenses if they are to be of any use. When we refer to cults and cult leaders, we are already distancing ourselves from the objects of our analysis. This is because cults are always already marginalized from society. They are understood to be at odds with cultural norms and defined by their own particular forms of extremism. If there is such a thing as an American history of cult activity, then Peoples Temple and the story of its Jonestown experiment are a central part of its narrative. And, it almost goes without saying, if this is so, then Jim Jones has a very important role to play in establishing the cast of characters in this historical drama. He is the quintessential American cult leader whose fantasies of domination became the stuff of nightmares. Casting Jones as a cult leader allows us to understand him and the history of Peoples Temple as somehow exceptional, on the fringe of the American story. Understanding Peoples Temple – and Jonestown in particular – as the by-product of a particular cult of personality surrounding Jones allows us to see this case as it relates to so many others in U.S. history.

Of course, Jones was neither the first nor the last preacher to find fame (and infamy) as a result of his purported healing powers. He is also not unique in the history of American political and cultural icons that have captivated the imaginations of their fellow citizens by claiming to have the one truly radical take on what ails us as a nation. He is not even the most extreme example of a powerful man who has become intoxicated on his own delusions of grandeur. There are so many examples – and so many contemporary examples at that – that spring to mind as I write this that it would be too easy to mention.

The creators of American Horror Story: Cult were obviously thinking about this when they were designing the drama that would unfold from week to week. No one figure is singled out as the most heinous or prime example of cult leader, and the writers of the season were careful to introduce very familiar figures from American history in ways that might estrange viewers’ sense of the present. Cult icons like Manson, Jones and Applewhite are introduced throughout the season to interrupt the flow of the more contemporaneous main plot, which, again, begins with and concerns the immediate aftermath of Trump’s election in 2016. Using artistic license, the show removes these cult leaders from the dustbin of history and gives them new life in the present: not only as shadows cast on the contemporary world, but reanimated ghosts reentering and haunting the future. We don’t see Donald Trump, but rather his followers, who, episode by episode, become more deranged and more violent. Cult leaders like Charles Manson and Jim Jones are not memories. Because the genre before us is horror, the show is able to creatively address matters of time (life and death, past and present). Brought back to life, entering the fray and offering words of counsel to their rightful heirs, the two zombie kings of personality return to oversee the cultivation of a new army of followers.

AHS: Cult does not want us to imagine that we are immune to the dangers facing the souls populating its show. Much like the America it conjures up, we live in a country that is haunted by its own contemporaneous cults of personality. And, as the title of the upcoming season,AHS: Apocalypse, seems to suggest, we may be blindly leading ourselves to our own doom. While the prominence of cults and cult leaders waxes and wanes in U.S. history, the unfolding megadrama of our fixation on and participation in cults of personality remains.

(Taylor Black is Assistant Professor of English at Duke University. His book, Time Out of Mind: Style and the Art of Becoming, is forthcoming. His previous article for the jonestown report is A Reckoning: Five Examinations of Tim Carter’s Essay. He can be reached at t.black@duke.edu.)