Over the years since the tragedy on November 18, 1978, there has been much discussion about what happened on that day, as well as what happened in the history of Jim Jones, Peoples Temple, and Jonestown prior to that final day. With the 40th anniversary of the tragedy now at hand, there have been countless documentary films that center upon the numerous people and events involved that have been made and shown; undoubtedly, many of those documentaries will be aired again this November.

The A&E Network got a jump on everything to follow. Its documentary, Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre included a device which raises both artistic and journalistic issues: the use of re-enactments of both people and events. There were moments in the film in which re-enacted events were seamlessly merged with actual footage and photos of Jonestown and the people who resided there. Unfortunately, the filmmaker didn’t bother to indicate any differentiation between the footage that was real and the film that wasn’t.

This article then will attempt to delve into those issues that exist in the making of re-enactments in order to better understand what, if any, standards exist within the genre for the use of such re-created film and sound. It will also discuss how such re-enactments may very well misinform viewers rather than inform them.

A Brief History of the Medium of Film

The new medium that came to be known as Motion Pictures or Films was first introduced to the public on a commercial scale by the Lumiere Brothers on December 28th, 1895, in Paris. Receiving a fee from each viewer to watch their production, the brothers screened 10 short films for their audience.

Three years later, in 1898, the concept of documentary films was introduced by Boleslaw Matuszewski in his book Une Nouvelle Source de l’Histoire (A New Source of History). According to Matuszewski, the new art form of the “motion picture” allowed historians to do better than to merely observe an event and describe it to others who weren’t present: historical events could now be on caught film, and presenting that film would be far more effective and accurate in explaining events, rather than asking viewers to imagine them. However, once early moviemakers realized that people were willing to pay to see their work, film changed from the recording of historical events to entertainment, which promised to be far more lucrative. The positive reception to films made for entertainment led to the creation of the Motion Picture Industry in the United States; by 1910, American-made films dominated this new artistic medium, and by 1920, Hollywood, California had become the center of the industry.

Three years later, in 1898, the concept of documentary films was introduced by Boleslaw Matuszewski in his book Une Nouvelle Source de l’Histoire (A New Source of History). According to Matuszewski, the new art form of the “motion picture” allowed historians to do better than to merely observe an event and describe it to others who weren’t present: historical events could now be on caught film, and presenting that film would be far more effective and accurate in explaining events, rather than asking viewers to imagine them. However, once early moviemakers realized that people were willing to pay to see their work, film changed from the recording of historical events to entertainment, which promised to be far more lucrative. The positive reception to films made for entertainment led to the creation of the Motion Picture Industry in the United States; by 1910, American-made films dominated this new artistic medium, and by 1920, Hollywood, California had become the center of the industry.

The Genre of Documentary Film

A documentary film is defined as “a movie that provides a factual record or report of an event, person, or place.” Originally meant to tell the ”non-fiction,” or truthful, version of an event or a person, documentaries were once considered as a bland movies genre, and compared to other forms of cinematic offerings – Romantic Comedies, Musicals, Action and Horror/Thriller – they were once not all that common or popular. Every now and again, though, a particular documentary has had a cultural significance that explained a certain “Zeitgeist” correlated with a time and place in history. Such documentaries also dealt with the people who either participated in the phenomenon that occurred, or who were touched on some sort of a personal level by what had happened.

Documentary films which drew from both tragic and uplifting real-life events were not like their fictional cousins in many ways, but primarily because they were seen as more of a teaching tool, and most movie-goers were looking to escape reality. Education was for school, not for recreation.

The first documentary film to actually garner public attention was Nanook of the North, a silent picture filmed by Robert Flaherty and issued in 1922. The film purported to detail the daily life of a native Inuk man living in the Canadian Arctic. It’s important to note that Nanook of the North was marketed as a documentary, but was in actuality a “docudrama.” The director interfered in the purity of the documentation process by making certain shots easier for the cameras of the time to film; in addition, there was flat-out scripting of how certain events should look when filmed, such as when Flaherty asked “Nanook” to use a spear while hunting, even though “Nanook” and his people were using guns for hunting at that time. Those who saw the film came away believing that they now knew what life was like for the Native Inuk people in the Canadian Arctic. They didn’t question the veracity of what they had seen on screen. They didn’t even think that they might need to do so. They believed that they had seen a true (i.e., truthful) documentary.

The first documentary film to actually garner public attention was Nanook of the North, a silent picture filmed by Robert Flaherty and issued in 1922. The film purported to detail the daily life of a native Inuk man living in the Canadian Arctic. It’s important to note that Nanook of the North was marketed as a documentary, but was in actuality a “docudrama.” The director interfered in the purity of the documentation process by making certain shots easier for the cameras of the time to film; in addition, there was flat-out scripting of how certain events should look when filmed, such as when Flaherty asked “Nanook” to use a spear while hunting, even though “Nanook” and his people were using guns for hunting at that time. Those who saw the film came away believing that they now knew what life was like for the Native Inuk people in the Canadian Arctic. They didn’t question the veracity of what they had seen on screen. They didn’t even think that they might need to do so. They believed that they had seen a true (i.e., truthful) documentary.

In the century since Nanook, documentary films have drawn in more viewers and become more and more profitable, to the point that major movie companies now make them an important part of their budgets and schedules.

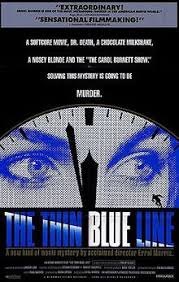

One of the most influential documentaries of all time was The Thin Blue Line, released in 1988. Made by Errol Morris, the film – like Nanook – steered from being a true documentary of historical events by using a great deal of “re-enactment footage” to tell the story. Randall Adams had been falsely convicted of the murder of a Dallas Police Officer in 1976. The film revealed that another individual was present at the time of the murder and could’ve been the shooter instead of Randall Adams. In addition, the re-enactments Morris made for his film sowed doubt as to whether Adams could himself have actually committed the crime. The numerous re-creations of events and witness interviews were so persuasive and the resulting public outrage over Adams’ imprisonment so great, that he was released from prison in 1989, one year after the documentary was released, and the Dallas Prosecutor decided to drop the case. This meant that Adams, after having spent 13 years of his life in jail, could finally live his life as a completely free man.

Morris’ use of scenes depicting the crime were seen not just as being important for the subject at hand, but for all documentaries. In 2008, Variety Magazine called the documentary “the most political work of cinema in the last 20 years.”

* * * * *

The public’s sentiment towards the documentary film has changed greatly from the years in which documentaries were viewed as nothing more than “boring teaching tools.” Some of them have become a box-office success on a par with the fictional movies that are released alongside of them. Given this rise in popularity, is there anything to be concerned about with what was once seen as merely “an educational tool” enjoying such a boost in popularity?

Indeed, there is. There are certain things that go into the making of documentaries that viewers may not even be aware of, and which could lead to great misunderstandings about the people and events featured in them. Of these, perhaps the thorniest issue is the use of re-enactments.

The purpose of re-enactments is usually to provide a context, to show what things looked or sounded like in regards to an event or person. The intent of a documentary is to explain what occurred historically, and to make their film more interesting and accessible to the viewers – especially where there is a lack of actual footage of the event – re-enactments can reveal cinematically what actually occurred (or at least, what occurred from the director’s point of view). But the very use of this device can cause the audience to come away with a false impression about what actually happened. For example, the filmmaker in 1922’s Nanook of the North was interested in showing the audience what it had once been like for the native Inuk people, rather than how things were currently, because he thought that subject was extremely interesting: clearly, though, he didn’t make any attempt to insure that those who saw his film would know the difference.

The Issues Inherent in the Use of Re-enactment Footage in Documentaries

Chief amongst the issues within documentary filmmaking, many documentaries do not make a point of delineating between what footage is re-enacted versus what is actual, historic footage. A fair number of documentary films use whatever real footage that they can find of the event, person or place, even as they use re-enactment footage in an attempt to “fill in the gaps.” Mixing the two types of film footage isn’t problematic on its own. It does become an issue, however, when the filmmaker doesn’t make it abundantly clear what is real and what is re-enacted. It’s far too easy for the viewer to believe that everything on the screen is exactly how things happened, if the filmmaker doesn’t make the effort to differentiate between the two. To their credit, many documentarians will make certain that all re-enactment footage is labeled, such as placing the term “Re-enactment,” in the corner of the re-created portions. Unfortunately, the practice is not universal, nor are there industry requirements or even guidelines for such labeling. The result often leaves the viewer believing that everything that they saw was a legitimate occurrence of the historical event. At the very least, the viewer often has to struggle to try and figure out what is actuality footage and what isn’t.

Those who watch modern documentaries don’t seem to mind the use of re-enactments, even when they’re badly staged or obviously incorrect. As a matter of fact, most viewers don’t even realize why a re-enactment could be an issue in a film that purports to show true and actual events. As blog author Jason Bailey wrote in 2015, “that once-controversial device is something [that] no one seems to mind all that much anymore.”

This is not to say there is no role for re-enactments. The acting out of historical scenes and/or events can indeed give one a feel for what it was like for the individuals who were present at the actual occurrence, but there’s a big difference between re-creations of events in film versus those re-enactments which can be viewed live. People going out on a summer’s day and watching the re-enactment of a Civil War battle are well aware that they are not seeing an actual battle, and maybe not even a second-by-second account of what literally happened. Rather, they know they are watching a re-creation, an interpretation of the event. In contrast, re-creations of events presented without disclaimers in documentary films curtail the ability of one to understand the differential.

The Effect of Public Acclaim for Morris’ The Thin Blue Line

After The Thin Blue Line was received with such public acclaim, would it be fair to say that other documentarians began to think that their films could do more than “illuminate an unknown truth” by using re-enactments of events? Is it possible that documentarians were drawn to the genre thinking that they could perhaps “make a difference” in the lives of those who were the focus of their films? It is true that the use of re-enactments began to rise, but to what purpose?

After The Thin Blue Line was received with such public acclaim, would it be fair to say that other documentarians began to think that their films could do more than “illuminate an unknown truth” by using re-enactments of events? Is it possible that documentarians were drawn to the genre thinking that they could perhaps “make a difference” in the lives of those who were the focus of their films? It is true that the use of re-enactments began to rise, but to what purpose?

Three different points on the spectrum of filmmaker intentions emerged as to the reason to use re-enactment footage: what this author calls Positive Intention, Neutral Intention, and Negative Intention re-enactments.

Positive Intention: Filmmakers of this genre might believe that they can genuinely help others with their works. Perhaps, with the use of re-created scenes, they can bring justice to long-suffering individuals and families, or give the public at large a better idea of what had truly happened. An example of a Positive Intention might be the example provided by The Thin Blue Line, for a filmmaker to clear the name of a wrongfully convicted individual by demonstrating how a witness’ account of what happened during the commission of a crime simply isn’t possible. Once exposed, the invalid testimony might encourage the public to demand the release of the falsely accused.

Neutral Intentions: These are the filmmakers who use re-enacted scenes without any intention of affecting the audience’s opinions, but rather to simply fill in “gaps” in the story that they are documenting. The creation of a scene with people boarding a train at a station in 1910 would have no other purpose than to show the dress and appearance of train passengers, the types of trains used, and the architecture of a train station. Such re-created film would be used only as a visual device, and adds nothing either positive or negative to the overall story.

Negative Intentions: The temptation in the use of re-enactments is to recreate historical occurrences that aren’t completely faithful to the facts or which speculates or goes beyond what is known about a subject, and some documentarians have yielded to that temptation. Some have gone even further by using re-enactments in order to push a personal agenda, to present a view of a piece of history that corresponds to how it could have been or, indeed, how the truth about the event has been suppressed. Again, without labeling, the viewer is often left without a means to discern actual truth from opinionated distortion.

The Issues Inherent in the Use of Voice-Overs in Documentaries

Documentary filmmakers are also given to hiring actors/actresses to read letters and documents that relate to the subject of the film, in an attempt to bring the impact of a human face or voice to the words. The voice-over could be of a letter of a historical figure, or perhaps an anonymous internal memo located within an organization’s or company’s files. Oftentimes – especially with letters or other texts written by a specific individual – the person himself or herself is dead, so the viewer is only hearing the words that the author wrote. The individual’s actual voice is missing.

Not being able to hear a person’s actual voice can be problematic for many reasons. The actor might not be getting the correct inflection of speech, or he might emphasize the wrong words in the letter/statement. This is not due to any ill intent, but it can still be wrong. As innocent of a mistake as that would be, it could still have unforeseen consequences: the documentary audience hearing that misinterpretation might form an opinion of an individual based upon what they hear in the voice of the actor, versus what is actually known about the author of the letter. That would certainly be enough input for the audience to make assumptions about the document’s author, and those beliefs formed would be incorrect.

There is, however, an even greater danger for misinterpretation, if a documentarian takes the liberty of deciding what the tone of the letter should be, based upon what the filmmaker personally believes about that individual being quoted. Even worse, filmmakers could – and have – intentionally had actors reading from letters use such tactics as manipulating tone of voice, etc., in order to get a personally desired effect out of the voice-over. As Joseph Lanthier wrote in 2011, “[It’s possible to] shepherd the audience into belief [of a subjective opinion] by implying the intensity of the interviewee’s authenticity.”

This cherry-picking of exactly what is emphasized in a letter or statement will influence how the viewer forms an opinion about the person who is “speaking.” Simply put, the tone of voice used by the actor is likely to give the audience the impression that the individual quoted was, indeed, given to the emotion associated with that tone. According to journalist Richard Brody, “[Verbal/read] Re-enactments aren’t ‘what-if’s,’ they’re ‘as-if’s,’ replete with approximations and suppositions” (Brody 2015). This means that voice-over re-creations can never accurately translate the intentions of those who wrote the documents highlighted in documentary films. These “approximations and suppositions” can have quite the negative affect on how historical individuals are perceived.

The Reason that Voice-Overs are Effective in Persuading Audience Opinion

The way that we interpret what we see and hear, and use it as a guide to the personality of another person, can shape our opinion of that person not just in that particular moment, but overall. Think about how you interpret the personality and intentions of strangers on a daily basis by interpreting their body language – especially facial expressions – and tone of voice. All humans do this. We’re programmed to do it. At the most basic levels of our cognition, that is how we determine whether or not someone is a danger to us. This rudimentary brain process is a survival mechanism, and survival is our most core drive as human beings. We cannot turn off this part of the brain, and oftentimes we don’t even realize that we are using that particular mechanism to figure out the intentions and general personality of another.

How greatly can what we hear read out loud in a documentary film affect our perception of others? Richard Brody of The New Yorker Magazine explains the impact of voice-overs in documentary films this way: “It’s the iconic connection of the physical world in the present tense to the past event in question… The bearing of witness is sacred, even in profane circumstances, because of this connection. It’s an act of virtual reincarnation, which is why the cinematic interview, the word brought to life on camera, has such dramatic force.” More bluntly, what we hear read aloud – and exactly how it’s read – in documentary voice-overs can literally define how we perceive the author of a letter or document.

Formal Criticism of Re-enactment Footage and Voice-overs in Documentaries

How do documentarians feel about the use of re-creations in the genre? Do they feel they have a “moral duty” to represent what they film in a truthful manner? And what do film critics think? According to Susan Kougall: “The use of re-enactment in documentary films has filmmakers, film theorists and critics divided. Some believe the use of re-enactments brings historical accuracy into question, while others feel it enhances history” (2015). Richard Brody, a film critic writing for the Culture section of The New Yorker magazine in 2015, said, “The re-enactment is the bane and the curse of the modern documentary film… [The re-enactment is] an act of virtual reincarnation, which is why the cinematic interview, the word brought to life on camera, has such dramatic force.”

The director of The Thin Blue Line commented himself on criticisms of his ground-breaking documentary work some 20 years after its release, defending it from those critics who argued that his reliance upon re-enactment footage was too great. Errol Morris said, “Critics don’t like re-enactments in documentary films, perhaps because they think that documentary images should come from the present, that the director should be ‘hands-off’. But a story in the past has to be re-enacted… There is no ‘veritas’ lens: no lens that provides a ‘truthful’ picture of events. There is… no cinematic truth” (Bailey 2015).

Final Thoughts

Does the use of re-enactments in documentaries affect how the viewers of such films view historical people, places and events? In the opinion of this author, yes, they do, without a doubt. The very fact that numerous documentaries do not delineate plainly which footage in a documentary is a recreation, and what is actuality footage, illustrates that the intent of those who use such recreations is not to tell the truth. It could be – and should be – a very easy thing to edit in the words “Re-enactment” over these scenes that are re-created for a documentary film, and yet a great majority of the filmmakers don’t do so. More times than not, it’s only logical to assume that re-enactments are not delineated from actuality footage because the documentarian wants to convince the audience that the re-created footage and voiceovers have the same amount of authenticity as the actuality footage does.

This is an issue that is both more characteristic and problematic in documentary filmmaking than other types of film media. Documentaries are supposed to be as truthful as possible, so people assume that any film that is labeled as a documentary is exactly that: the documented truth. With that belief in mind, people don’t question what they see or hear, but rather they implicitly trust that the filmmaker is sticking to the truth in educating and enlightening the public on a subject. We are often not aware of how re-enactment footage and voice-overs can misguide us in regards to our beliefs about both historical individuals and events. As human beings, we know we like to have clean-cut answers for our questions. This can lead to a myriad of issues for the movie-going public who receives the misinterpreted history – whether by design or accident – and who can actually spread misinformation Documentary filmmakers who engage in “guessing the answer” to the question of “what happened?” with re-enactment footage do a disservice to their viewers on a larger scale. Their theories and opinions of one individual become the truth, spread to thousands of people through a single film. These subjective ideas take away from actuality, and can give power to false information, conspiracy theories, and harmful misunderstandings.

Proceeding with Documentary Films in the Future

It is urgent that documentary filmmakers cease their harmful behavior of using inaccurate re-enactments of events in film footage and voice-overs within the documentary genre before too much damage is done to the understanding of historical individuals and events. I believe strongly that some sort of universal standard for re-enactments in documentaries be created and enforced, preferably by a group or board such as the Motion Picture Association of America. Documentaries should be rated for their veracity, so that the public knows what sort of weight should be given to the information disseminated within them; indeed, the rating system could be as simple as to note what percentage of the documentary film uses re-enactment footage and voiceovers, so that the viewer knows when the actuality of a person/event could be in question.

Without some sort of guide for the documentary film viewer to go by, each film might as well begin with a standardized warning on the screen that says reads: “Caution: Historical inaccuracies in this film may be greater than you think.”

Work Cited

Bailey, Jason. “The Case for Reenactment in Documentary Cinema.” 5 February 2015. http://flavorwire.com?503086/the-case-for-reenactment-in-documentary-cinema.

Brody, Richard. “Why Reenactments Never Work.” 20 March 2015. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/just-say-no-to-reenactments-jinx-robert-durst.

Kougall, Susan. “Reenactments in Documentary Films: Is there an Authentic Truth In Documentary?” 17 April 2015. http://scriptmag.com/features/reenactments-documentary-films-authentic-truth-documentary.

Lanthier, Joseph. “Do You Swear to Reenact the Truth? Dramatized Testimony In Documentary Film.” 1 May 2011. http://documentary.org/magazine/do-you-swear-Reenact-truth-dramatized-testimony-documentary-film.

Svetvilas, Chuleenan. “Hybrid Reality: When Documentary and Fiction Breed to Create a Better Truth.” 30 June 2004. http://documentary.org/feature/hybrid-reality-when-documentary-and-fiction-breed-create-better-truth.

(Bonnie Yates is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. Her other article in this edition of the jonestown report is Filling in Gaps in Jonestown Video with Re-Enactments. Her previous articles may be found here. She may be reached here.)