(This blogpost was originally published on 26 October 2019.)

I recently saw a tweet referring to Jim Jones’ followers – the members of Peoples Temple who died at Jonestown in 1978 – as brainwashed zombies. Every time I hear this, I feel saddened but not surprised. Whilst the people who died at Jonestown have been maligned for 40 years, the media narrative which started in the days after the massacre and has continued ever since of zealots mindlessly slaughtering their children before taking their own lives is very far from the truth. Like everything in life the real story is far more complicated.

So here it is: why everything you know about Jonestown is wrong (and why you should never joke about “drinking the kool aid”). Strap in, it’s going to be a long one.

This began as a Twitter thread in response to the disparaging tweet, but I wanted to expand on some of the points. Why do this? Because almost everyone who died at Jonestown was a good person working hard for a better, more equal future. They deserve better than the racism and slurs which have tainted the discourse of their lives and deaths for 40 years. Jonestown was only the final year – the final day – in a story of Peoples Temple which stretches back over 20 years, across the US and South America. So we have to learn a little bit of the history.

Jim Jones, started his preaching career as part of the Assemblies of God (Pentecostal) Church in Indiana in the 50s, whilst still in his early 20s. From the beginning he stood out: he preached the socialist gospel and a racially integrated church – unheard of in the Midwest at the time. Services were advertised as full gospel, interracial interdenominational services with “miracle healing” services.

Jones quickly gained a high profile in the local area. But due to the interracial membership of the congregation, there was much local opposition to the church in the conservative Indiana of the 1950s. Meanwhile, it was the height of the Cold War; Jones read a magazine article on the Earth’s safest places in the event of a nuclear explosion. By the mid 1960s, he decided to move the church to a more conducive location in Ukiah, California, named as one of the safest places to see out a nuclear apocalypse. Several dozen loyal followers accompanied Jones and his family on the road trip across America. Some of these families were there till the end.

In Ukiah, California, Peoples Temple set up as more than a mere church: they ran aged care and day care facilities, group homes for foster children and communal living. There were crops, a community centre and pool.

At some stage in the 1960s Jim Jones visited South America for some years. We don’t know exactly where he went or why, though it seems he was visiting some of the other sites named as places to ride out the aftermath of nuclear war. He visited locales in Brazil and at some stage Guyana.

Back in California, Jones grew restless. He had bigger ambitions for Peoples Temple than Ukiah. In the early 1970s he moved Peoples Temple to San Francisco, and established a satellite church in Los Angeles. This is when Peoples Temple really took off. Jones preached from the Bible, but also a message of total equality: shared wealth and resources, no racism, no sexism. Not just for a small group, but for larger society. In the fraught America of the 1970s, it was a message that appealed.

It’s important to remember Jones was no Charles Manson. He was not a scruffy ex con speaking of portals in the desert. He was an educated, articulate, extremely charismatic man. This is not a defence of Jones, as I’ll get to.

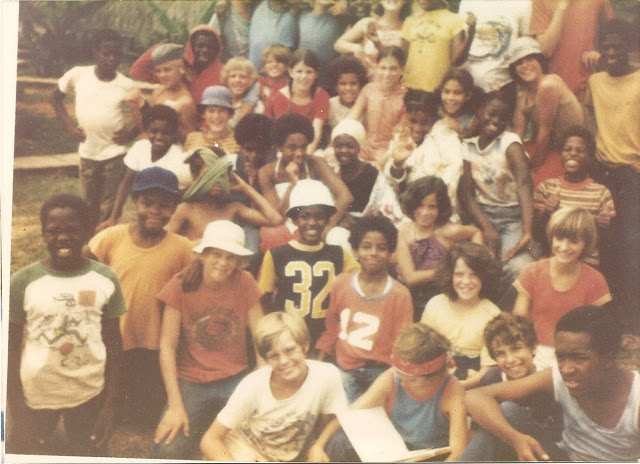

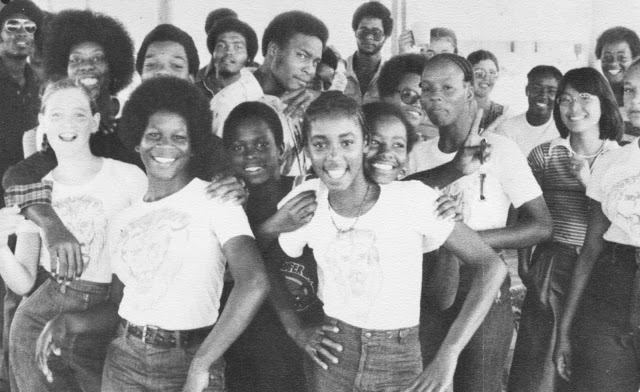

Peoples Temple held several weekly services, members travelling between SF and LA on buses the church owned. They also began cross country trips where Jones would preach, recruiting members to come to California and join the project in social living. Membership soared. Jim Jones offered something for everyone. To young educated whites, he offered a chance to join work for the betterment of humanity. The mood among civil rights and social activists in the 1970s was one of malaise. America was out of Vietnam, at an appalling human cost. Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated, the economy was tanking amid global oil shortages, and the dream of the 1960s was dead. Peoples Temple gave the socially active a reason to hope again, working for the betterment of society.

For young black people from the inner cities, Peoples Temple offered financial security, equality and hope, free from the poverty, crime and racism of the ghettos. For elderly black women from the U.S. South – some born to parents who had been slaves – he offered the revivalist preaching they were used to, a message of racial equality, and a chance to avoid lonely old age by choosing communal life.

Many people signed over their houses and life savings to join and live communally with Peoples Temple in California. Numbers are disputed, but by the mid 1970s the church had at least several thousand members – and had accumulated great wealth.

Jones gave thundering sermons and performed faith healings. But not all members were there for the religion. Many atheists and agnostics joined for the chance to be part of the project. Peoples Temple offered shelter, medical care, counselling, aged and child care, drug and alcohol detox. Most of the members by this stage were urban African Americans from a Christian background. Everyone shared the belief in re-distribution of wealth, racial equality, and a belief a better society was possible.

In 1974, a small group of Temple faithful traveled to Guyana to establish the Peoples Temple agricultural project. It was imagined that eventually this would be a place for temple members to live in a purely communal society away from the violence and racism of the US. A rotating group of around 50 people would work on establishing Jonestown over the next few years.

But we can’t discuss Peoples Temple without talking about its dark side. The Church took care of its own. The good and the bad. The church had strict rules for members – no drugs or alcohol, polished appearance, permission required to start relationships, and very long hours of work. Many members would work their full time day jobs then spend all night at the temple – in services, cleaning, on food drives, overnight at church care facilities, producing Temple media. This endless work was a running theme through the life of the movement. And the Temple handled its own discipline. Members lived communally and were expected to report on each other – for drinking, illicit sex, complaining. Punishments were severe – humiliation and beatings in front of group meetings. Temple members who wanted to leave often could not. They’d signed their property over to the church. The Temple had a record of harassing and threatening former members, who formed support groups.

Despite the ethos of racial equality, and that the membership was around 75% African American, the leadership group was mostly white, mostly women, many from the original Indiana church families. Almost inevitably, Jones has sexual relationships with many of them. He had a long term relationship with a woman, Carolyn Moore Layton, who bore his child and headed much of the day to day management work in the life of Jonestown. Jones also pursued sexual relations with other young women, and men, in and out of the Temple. In 1973, he was arrested on a lewd conduct charge for propositioning an undercover police officer in a Hollywood adult theatre. Temple lawyers were able to get the charges dropped and the scandal hushed up. The general membership of Peoples Temple were unaware of any of these proclivities of their beloved leader.

By 1976, Jim Jones was a powerful man in San Francisco, elected housing authority chairman, regularly in the media and seen as vital in George Moscone’s mayoral victory. Peoples Temple was seen as a model of social service and justice, succeeding where the government and social services couldn’t. The governor and lieutenant governor of California attended a testimonial dinner for Jones, where he was toasted as a combination of Mao Zedung, Martin Luther King Jr, Angela Davis and Albert Einstein by a California assemblyman. What’s that about power corrupting? Jones even met with VP candidate Walter Mondale and First Lady Rosalynn Carter (Mrs Carter also met John Wayne Gacy – that woman was not a good judge of character).

Peoples Temple members attended rallies for left wing issues in their hundreds. By now the Temple wasn’t a church, not a cult – it was a social movement. Of course, all this adulation and activity is going to attract media attention.

Investigative journalists in San Francisco had been studying the Temple for years. It all came to crisis in mid 1977, when New West magazine published an expose where former members alleged they were physically, mentally and sexually abused in Peoples Temple. That’s when Jones decided to blow this popsicle stand. The week the article was published he left the US for Guyana, giving orders for many hundreds of his followers to join him. They would live in the Peoples Temple agricultural project – Jonestown.

Why did Jones abruptly leave the country instead of defending himself and his church? Fear of loss of face and status? We don’t know, but it’s a theme that would recur. We do know that by now, Jones was heavily using drugs, a combination of amphetamines and barbiturates. Temple members outside the inner circle, however, never knew any of this, nor of Jones’s sexual peccadilloes with young women. But the drug use holds the key to his increasingly erratic behaviour and downward physical and mental spiral over the next, last year.

A small group of Temple members had been working the Jonestown site for years – clearing the jungle, establishing crops, building houses and outbuildings. Members back in the US were shown footage of what was a beautiful place – pure community.

Jonestown would be free of the violence, racism and poverty of the States. It was a jungle utopia where Temple members could live a peaceful communal life. Most members were keen to go, to live this life. They did not go to Guyana to die.

But Jonestown was not ready for an influx of 1000+ members over a few months. It was never intended to house more than a few hundred. When members arrived, housing was crowded, food monotonous, long work hours a constant. Still many were happy. Jonestown quickly established a tightly run and efficient community. Members with college degrees and experience took over running of the medical department, school, day care, agriculture, construction, food service and security. Jonestown functioned, on many levels. I’ve read the learning plans for the grade levels in the school. They’re thorough. Even the day care had a detailed program of play times, addressing key learning areas and milestones. In the evening the community had classes, film nights, talent shows. The people who went to Jonestown weren’t following Jones because they thought he was a God. They didn’t go there to die. They went there to live, to build a better community.

So why did they die, and how could they poison their kids? We’re getting there.

As I mentioned, Jim Jones was taking a lot of drugs. What does amphetamine use make you? Paranoid. He became paranoid the community would be attacked – by the Guyanese army, the CIA, even members’ relatives. He beefed up security. There were now armed patrols. To create a siege mentality, an increasingly paranoid Jones and his small inner circle devised a series of staged attacks on the settlement. Members were told they would be captured, shot, their children sent to re-education camps in the US.

In his sleepless amphetamine-induced manias, Jones would recite speeches that went on for many hours, haranguing members with tales of the tortures being committed back in the US, concentration camps for Black people. Lacking access to the outside world members had no way of knowing how much of any of this was true. At regular community meetings Jones delivered the same reports of fascist horrors in America. Members were left terrified of what might happen if Jonestown was attacked.

The punishments for infractions continued, more severe than ever before. Residents who broke rules or were heard to be complaining about Jones and wanting to return to the US could be assigned to perform hard physical labour on the “learning crew” or sentenced to spend hours or days sealed in a coffin like box devoid of light (sometimes with the added threat of snakes). For the recalcitrant and severe agitators, the worst fate was being sent to the “extended care unit”, a medical facility where victims were medicated round the clock with large doses of Thorazine and other anti-psychotics to keep them docile and sedated.

But I do want to point out that there were no religious services once the Temple was in Guyana. Jim Jones threatened horrors of the real world, not a fantasy world. There was no imagined space ship to take them away, but the very real US military.

Despite all this, many were happy in Jonestown. They escaped the racism and poverty of ghetto life in the US to a place they were building with their own hands, every day.

For others, it was hell on Earth, one with no escape. Residents’ passports were confiscated on arrival at Jonestown. There were no phones, all mail was censored, armed patrols of the site, the nearest town 7 miles away on a muddy road through thick jungle of north west Guyana.

In the last months, conditions deteriorated. Food got worse – a diet of mostly rice and beans – work was endless, with all except the very old and very young expected to work in the fields at least sometimes. Jones’ sermons on threats and horror played on the loudspeakers. Incidentally, there was no reason for such limited food. The land of Jonestown was poor for growing crops, thin and rocky. But the Temple had money. Around 1/3 of members were elderly and the church received tens of thousands a month from their social security checks. Seems Jones was hoarding money… Like he was hoarding his people. Anyway, survivors have reported morale got worse in the last months. Everyone was hungry, scared, depressed and so exhausted they couldn’t think straight.

Amid all this, relatives back in America were desperate for news of their loved ones and agitating to know what was happening. They contacted Congressman Leo Ryan, from San Francisco, who agreed to lead a congressional delegation, accompanied by journalists. Jones was terrified, but was persuaded to let them in.

Leo Ryan and his group arrived on November 17, 1978. Ryan was given a tour of Jonestown, declaring himself impressed with what they’d achieved with their community in the jungle. That night, the community gave a reception for Ryan in the pavilion. Everyone was perked up by a rare, decent dinner with meat. There were speeches and dancing. A band played. Children clapped and cheered.

There’s video from that evening which I share because Jonestown’s main vocalist, Deanna Wilkinson, seen performing here, has one of the most amazing voices I’ve ever heard. She deserves to be remembered.

But during the concert, several members quietly told members of Ryan’s party they were being held prisoner and wanted to leave. Ryan covertly told them he would lead a group of anyone who wanted to escape the next day.

On November 18, 1978 after some staged niceties Ryan informed Jones that several defectors wanted to leave. Jones, ashen faced, went into a frozen panic. He was terrified of any threats to his community. Trucks were arranged for the defectors. Only 20ish members left with Ryan – 5% of the total residents of Jonestown. But Jones didn’t see it that way. Someone had taken his people. Where there was one exodus, there would be others. Jones and his lieutenants decided to put into action a plan which had been brewing, unbeknownst to residents, for a long time.

Whilst the Temple was still headquartered in San Francisco, a New Year’s Eve party was held for the most loyal followers. At the party, Jones offered the attendees wine – a rare treat, as alcohol was usually forbidden for Peoples Temple members. Once everyone had a glass of wine, Jones informed them the drink was laced with poison, and in 15 minutes they would all die. After time for the attendees to react with stunned horror, Jones explained that the wine was not tainted; this was merely a loyalty test, to see who was ready to die for the Temple.

In Guyana, another suicide drill was held in February 1978. This time, it involved the entire Temple membership, who were told in advance that outside forces were threatening the Temple and they must take a drink of poisoned punch to avoid falling into the enemy’s hands. Temple member Edith Roller, a former college professor and Jones loyalist (although not a member of the leadership group) who kept a detailed journal of her time in Jonestown, described the experience:

At length Jim stated that the political situation showed no signs of clearing up and that we had no alternative but revolutionary suicide. He had already given instructions to make the necessary arrangements. All would be given a potion, juice combined with a potent poison. After taking it, we would die painlessly in about 45 minutes. Those who were leaders and brave would take it last. He would be the last to die and would make sure all were dead. Lines were formed as a container with the potion in it with cups was brought in by the medical staff. At the beginning those who had reservations were allowed to express them, but those who did were required to be first. As far as I could see once the procession started, very, very few made any protest.

I shuddered. I regretted dying as I feel I have years of work and experience ahead of me, not least of which is the writing I wish to do about this whole remarkable story. It seemed bad luck that just when I had come to Jonestown and had a chance to use my talents as a teacher, I should be cut short. Nevertheless, I am 62 and I think of those who are younger, especially the children, with all their potential. I looked around me. Many had glowing eyes. It was awesome. Even the children were very quiet. I looked at the beautiful sky surrounding us.

The most poignant thought of all was that the greatness that is Jim Jones would not come to fruition. Was this movement he had nurtured to come to naught, to a pile of dead bodies and an abandoned agricultural experiment in the small country of Guyana? He is the most remarkable man who has ever lived. Is this what he will be remembered for?

At intervals as the line went down the pavilion and crossed the room and came down the middle, I contemplated the experience of death. Another Shakespeare character, I believe it was, said, “We owe God a death.” I had to die sometime. But I must say I didn’t look forward to it with joy. At that particular moment I neither wanted to cease to exist, to be absorbed in to the Universal Essence, nor to be re-incarnated and start all over again.

However, it was a new sensation and in a certain and peculiar way, I was enjoying it, just the experience. Everything was very vivid. I was fonder of those around me than I had ever been. It was remarkable how disciplined and obedient they were. The look in their eyes showed they knew the importance what they were doing. I especially noticed the children, who were very quiet

Diane told us the next day that many parents came up to their children to give them a last embrace.

Some people were beginning to collapse. I saw one woman being carried out. I didn’t know the passage of time. It must be about 45 minutes since we have started taking the potion. I was annoyed that I did not have my watch. Then I was amused at myself. When one is about to die, what difference does it make what time it is? I couldn’t very well write in my journal: “I died at 5:30 p.m. on the 16th of February 1978.”

I had only a few minutes left until I would take the potion. I was going to be a credit to myself. I would take the potion without hesitation. I would just like to sit down on the grass and in a few minutes, I would pass out. That would be the end.

Then I heard Jim’s voice, quite quietly he was saying, “You didn’t take anything. You had only punch with something a little stronger in it.” He went ahead to explain the people who were passing out or feeling dizzy. “The mind is very powerful.” He told us we should have known that though revolutionary suicide might be sometime necessary, he would have had much more to say about it, had it been real.

One little boy, Irvin Perkins, I believe said, when he learned of the potion, “Oh boy, I’ll get off learning crew.” In a way, a great many of the seniors said that they were grateful to die. They had suffered so much. I think many people regretted that they weren’t going to die. In a way, I too, regretted that I was not going to be off learning crew. Back to the sound and fury of life.

Following the suicide drill, the membership got on with the sound and fury of their lives as best they could, but mass suicide became an obsession for the inner circle. Extant notes and letters show numerous discussions between Jones and members of the leadership on the practicalities and necessity of mass death of Jonestown residents. At Jones’s instigation, the Jonestown doctor, Larry Schacht, began ordering large quantities of cyanide under the guise of using it to clean gold. Jones and Schacht discussed testing the poison on pigs to determine the best method to kill people. Schacht devised a potion where the cyanide would be mixed with barbituates, to lessen the pain and terror of death. On November 18, that failed to work – the cyanide began working on human bodies long before the valium in the punch could take hold.

Jones had a plan in place for mass death. And at some point during Leo Ryan’s visit and the defections, he decided it was time for Jonestown to die. As with the New West article, when faced with a threat, he decided to escape – only this time, he was leading his followers not to a new life, but to their deaths. He gathered his loyal deputies and told them it was time to enact their horrific plan. The punch was prepared.

We will never be sure of the exact events but at some stage, Jones sent a group of armed, loyal followers to murder Ryan and the journalists as they waited to board aircraft out of the jungle. Accompanying Ryan on his trip was his assistant, Jackie Speier. She was shot 5 times on the jungle airstrip and waited 22 hours for medical help. She ran for Congress in 2008 and still sits there today.

Back at Jonestown, a demoralised and worried membership gathered for a community meeting. Jones informed them that the gunmen had in fact shot the Congressman’s aircraft down. The Guyanese army would be arriving soon to capture the residents. They would all have to die.

Some residents announced they were ready to follow Jones to the next plane. Others… Who knows. But they didn’t have a choice. Armed guards surrounded the pavilion. Everyone had to die, whether they wanted to or not. A vat containing purple flavour aid (NOT kool aid) laced with sedatives and cyanide was brought to the pavilion.

The very few survivors have reported the poisoning started with babies pulled from their mother’s arms, purple death squirted down their throats. The leadership figured once the children died, the rest would lose the will to live and go willingly. And there were 304 children murdered that day. Please don’t joke about drinking the kool aid. It wasn’t brainwashed zombies. It was murdered children.

I’m deliberately leaving out some of the most horrifying parts, but the leadership were forcing children to drink. The elderly – who made up another 1/3 of the members – were forcibly injected, some still in their bunks where they lay unable to make it to the meeting.

So that’s – at least – 2/3 of the deaths at Jonestown that were murder. What of the adults? They’d seen their kids die. They were exhausted to breaking point. They sincerely believed they would be captured and interned or killed. Some did choose the death. Some did administer the concoction to their own children. But I can’t see them as evil. I certainly don’t see them as mindlessly murdering their kids on the orders of Jim Jones.

And if Temple members themselves weren’t convinced, there were the armed guards making sure everyone died. The only survivors were a very few people who played dead, or were given tasks to leave the community to deliver messages of the end of Jonestown. If the deaths at Jonestown were completely voluntary, you would expect that out of a thousand people, at least a few would have chosen not to take the poison, and been able to walk away. But nobody did. Not one. The only survivors were those who hid during that last meeting, were able to run off after creating a diversion, or were given tasks by the Jonestown leadership to relay cash and messages to the outside world. Try getting a thousand people to agree on anything. Heck try getting your colleagues to agree on a team lunch. But nine hundred people in Jonestown all agreed with Jim Jones’ horrific decision to end Peoples Temple in a bloodbath? Not a single dissenter was allowed to refuse the cyanide and survive to tell about it?

In the end, 909 people were dead. 304 were children. 186 were seniors. For all his talk of bravery, in the end Jim Jones did not share the cyanide laced drink that killed his followers. He died of a gunshot wound to the head; it’s unknown if he pulled the trigger himself, or asked an aide to do it.

The indignities for Jonestown continued after death, due to the US government’s horrendous mishandling of the crime scene – making it impossible to know exactly how people died. None of the usual protocols for disaster scene recovery were followed. The Guyanese chief pathologist, Dr Leslie Mootoo, arrived in Jonestown late on Monday 20 November 1978, and spent several hours the next day – and after the bodies had been laying in the tropical heat for nearly three days – examining the site. Dr Mootoo visually inspected the bodies, apparently performing some limited dissection on Jim Jones and Ann Moore, and taking toxicology samples from sixy four bodies, according to his initial testimony (Dr Mootoo’s accounts of his actions that day would change over time). Two American doctors, Dr Bruce Poitrast and Dr Lynn Crook, attended the Jonestown site, and examined the bodies visually, but took no samples from the bodies and performed no chemical analysis of the empty containers and syringes they found at the site. Drs Poitrast and Crook nevertheless concluded all the Jonestown victims, with the exception of Anne Moore and Jim Jones, died from cyanide poisoning, and recommended the bodies be buried on site. No autopsies of any of the people who died at the Jonestown site were performed in Guyana.

Apart from these cursory examinations, the bodies were left in place for days, rotting in the tropical heat, whilst bureaucrats argued what to do with them. The Guyanese government rejected the proposal to bury the bodies on site, fearing the notoriety such a mass grave would cause. The U.S. Army was eventually sent in to retrieve the bodies, some of which had been lying in the rain and sun for up to ten days before they were transported to Dover Air Force Base in Delaware.

Once the bodies were repatriated to the United States, and almost a month after the deaths, 7 bodies were selected for autopsy. By this stage, the effects of decomposition, the kerosene poured on bodies to reduce insect infestation, and embalming carried out at Dover made the autopsies almost useless. Of the remaining 902, we will simply never know who swallowed the poison willingly or under duress, who was forcibly injected, or indeed who may have been shot.

This was possible in the immediate aftermath, when the narrative of crazy cultists took hold. The Jonestown dead were no longer people with families and dreams and lives. They were a unified mass of Jones devotees who’d blindly followed him to death.

There was a great ugly streak of racism in this. 2/3 of those who died at Jonestown were black. Many were from impoverished backgrounds. Their surviving family members were a less privileged group in access to the media. The narrative was set.

There was a great ugly streak of racism in this. 2/3 of those who died at Jonestown were black. Many were from impoverished backgrounds. Their surviving family members were a less privileged group in access to the media. The narrative was set.

The government announced it would charge families to transport the bodies from Dover to California, where most relatives lived (this act of petty cruelty was justified by the sadly familiar refrain that “taxpayers’ money” shouldn’t be wasted on crazy cultists). Many could not afford to claim their relatives; others were too ashamed. The unclaimed bodies languished for months before Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California offered to take them. Over 400 bodies – including the vast majority of Temple children, unable to be identified due to the absence of fingerprint records – were buried there in a mass grave in May 1979. A simple tombstone marked the site for many years. In 2011, a new memorial was unveiled, with panels featuring the names of all those who died in Jonestown.

In the years since, the tale has become muddied, confused with cult deaths since. Jonestown? Isn’t that where they wore white sheets and died to follow a space ship? After they murdered their kids? That’s not what happened.

There was Jones, out of his mind on drugs, paranoid and possessive. Terrified of loss of his people, his movement, his reputation as a great man, he decided to unleash a massacre. There were his inner circle who for their own unknown reasons worked to made his plans reality.

But most of those in Jonestown were people prepared to work for a dream of equality. They were good people who don’t deserve to be remembered this way. Here are the faces of those who died in Jonestown. Please remember them this way, and not as brainwashed zombies. I plan to tell the stories of some of those people in another post soon.

In the meantime, please don’t joke about drinking the kool aid.