“Would you write something about Stan? He is one of the only ones that has nothing about him; no memories or remembrance.”

“Would you write something about Stan? He is one of the only ones that has nothing about him; no memories or remembrance.”

I am surprised when the editor of this site made this request about my brother – why he asked me to do it, why no one else had contributed a memory – and then it hits me: I am now one of the only ones left who can remember him. I sadly am now truly one of the only ones left who can remember Stanley.

For the 40th anniversary I wrote:

When I no longer remember those we have lost they will no longer exist… so I must remember.

I must remember who they were, what they strived for and lived for. What they dreamed of.

I must remember their laughter, their love and their incredible will to create a new world.

I must remember the world they dreamed of, of peace, no war. No injustice, no racism. A place to raise our interracial children and families. To be together and build this dream together.

I must also remember that to believe blindly without question is not true belief but rather another form of trading one’s freedom and liberty away. I must also remember to question all manner of belief and to search myself for blindness of all types.

In doing that I remember our people who forged a life together, bound together, so precious till the end, so precious that they laid down those lives together.

I must remember them and who they were, what they stood for, what they believed, and when I remember,

I am saying, I remember you, I remember what you dreamed of, I remember your life.

I remember you and you lived a life that mattered.

You still matter, as long as I remember.

You still exist, as long as I remember.

But that was more about the entire Jonestown community than any one member of it. In order to write something about Stan, I asked around to those who may have had contact with him during the two years he and my other brother Cliff were in Jonestown. I had no direct contact, though I did receive pictures and heard from others how my brothers were doing. I wanted to know more about how he was perceived, how he worked and got along with others. More about him as a person. I didn’t want to write something glowing or what a great guy he was and then hear he as a jerk. Cliff, who did come back from Guyana, didn’t talk much about Stan, so I was really surprised when I read the interview Cliff did on the 30th anniversary with a local newspaper, and what he said about Stanley. I will also say that Cliff later told me how he regretted that interview, felt his words had been twisted and misquoted. He never spoke publicly about Stan again.

In writing about Stan, I want to also acknowledge and be sensitive to the fact that he was identified as the driver of the tractor to the airstrip that day and that he is considered an accomplice in those murders.

So with all that said…

To know Stanley, you probably have to know more about his family, our family and that has been something I’ve been reluctant to share, but for Stanley I will.

Our family joined Peoples Temple in Redwood Valley in the 1960’s, during peace, love and hippie days.

The fight for Civil Rights was not in the rearview mirror, even though the Civil Rights Act was signed in 1964. Segregation was still real, MLK was murdered in 1968, and interracial families, marriages, relationships were still hard fought for.

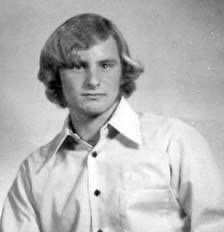

Stan was 9 when we joined the church. This is the only picture I have of Stanley in Redwood Valley. He was probably 6 or 7 here.

Stan was 9 when we joined the church. This is the only picture I have of Stanley in Redwood Valley. He was probably 6 or 7 here.

People say family units were purposefully and methodically dismantled and destroyed in Peoples Temple but that was not the case for us. Our parents had divorced, and my stepdad – Stan’s dad – had left the church, leaving our mom to care for and raise three rowdy boys while working two jobs. I was in college, living in the college dorms during the week and at the Ranch on weekends. There were always other children and teenagers staying with my mom and the family on Road H, but the boys were often too much for our mom to handle. Stanley eventually went to live with Jack and Rheaviana Beam, where he got the structure and attention he needed during those early teenage years. Our mother left the church shortly after. We had no contact with her for the six years before Jonestown happened.

As an older sister, I didn’t pay much attention to Stanley (or my other brothers either) except in how they got me into trouble by not doing their chores. In the early years he was a typical middle child, quiet and just kinda “there,” though he did have this amazing knack, as even a toddler, of how to take things apart – like clocks and machinery – and then figure out how to put them back together. In the church, though, he was “Stan the Man,” with a “I can do this” cocky attitude about fixing cars and the buses that wasn’t always appreciated coming from a 12-year-old, but I think he eventually grew into himself and his talents in Jonestown.

As an older sister, I didn’t pay much attention to Stanley (or my other brothers either) except in how they got me into trouble by not doing their chores. In the early years he was a typical middle child, quiet and just kinda “there,” though he did have this amazing knack, as even a toddler, of how to take things apart – like clocks and machinery – and then figure out how to put them back together. In the church, though, he was “Stan the Man,” with a “I can do this” cocky attitude about fixing cars and the buses that wasn’t always appreciated coming from a 12-year-old, but I think he eventually grew into himself and his talents in Jonestown.

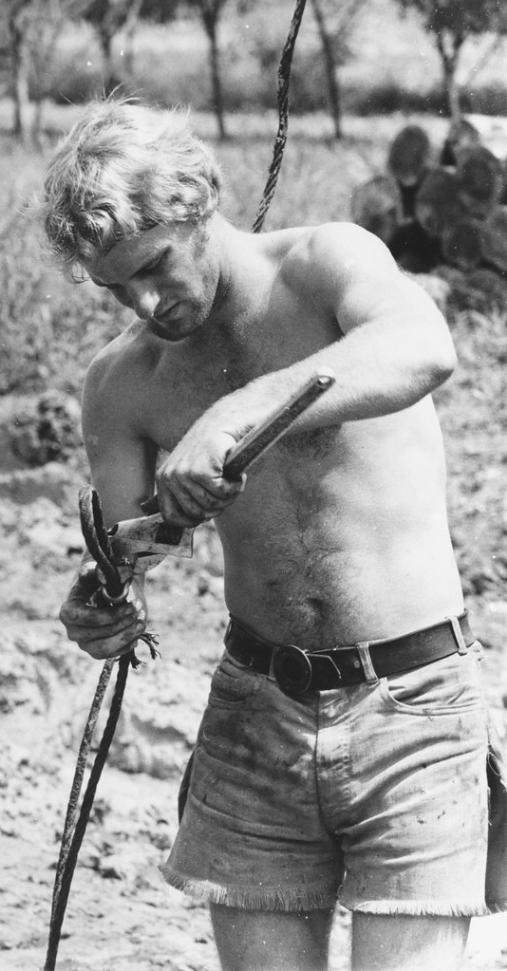

Stanley left for Guyana in 1977 at age 17. He seemed to have found his niche as an equipment mechanic, tractor driver and construction worker. I would get reports from Marcie and letters from others telling me about his work and how much he loved Guyana. When I checked that with one of his peers/ one of the survivors who returned, he said:

Stanley left for Guyana in 1977 at age 17. He seemed to have found his niche as an equipment mechanic, tractor driver and construction worker. I would get reports from Marcie and letters from others telling me about his work and how much he loved Guyana. When I checked that with one of his peers/ one of the survivors who returned, he said:

Thinking of Stan I can picture his face as if it was yesterday. Stan always had a big smile on his face (much like yours J ) and I think he was happy. Stan was most happy being productive but mostly helping others. When I knew him in the Valley he was polite and would say hi but keep to himself. In Jonestown, it’s as if he found inner peace and Stan flourished. You could always find Stan on a tractor driving people around and pulling heavy equipment to start a construction project. He was always waving and saying hello to everyone and making sure whatever task he was doing had his full attention and then be off doing something else. If something needed to be done you could hear Stan say “I’ll do it.” I’m sure Stan enjoyed his free time but it seemed (to me) that Stan was happiest doing his work and being a man around JT that got things done.

The one note I got from Stan along with several pictures was short and to the point. “We’re getting it ready for you, sis,” he wrote. “We’re building the promised land.” Those pictures still hang on my wall.

The one note I got from Stan along with several pictures was short and to the point. “We’re getting it ready for you, sis,” he wrote. “We’re building the promised land.” Those pictures still hang on my wall.

Stan lived more than half of his life in Peoples Temple. It was his family and his world. I believe he felt he had a place and a purpose there.

Stanley was 19 years old when he died in Jonestown that day. There are accounts that Stan was driving the tractor of the gunmen to the airstrip that day, and some even say he was one of the gunmen. I couldn’t speak to that then nor can I now, 40 years later.

That said, Clifford, my other brother who was there and did survive, struggled with the guilt of surviving when over 900 members of our family did not. Cliff rarely spoke about Jonestown, but when he did he talked about how paranoid Jim had gotten and how badly things had deteriorated in the last few months. He also said Stanley loved it there, and it was the promise of the future and the potential of what was being accomplished in the jungle that kept them going.

This piece isn’t about Cliff, but I can’t talk about Stan without Cliff. They were 13 months apart in age and worlds apart in looks and demeanor. Both grew up in homes of Peoples Temple members, both went to Guyana and were there for over two years. They were salt and pepper. Clifford was 18 when he returned from Guyana. He married twice, and had children of his own, who are themselves now grown. He passed away in 2017, the same year as our other brother Danny Curtin and our mother.

So when I was asked to write something about Stanley, I realized I am one of the only ones left that can remember him … but as long as I can remember, he and all the others still exist.

(Deborah Harper and her family joined Peoples Temple in Redwood Valley in 1968. Her brothers, her cousin, his wife and son and her adopted son died in Jonestown. She may be reached through this website.)