Based on the 2015 novel of the same name, White Nights, Black Paradise by Sikivu Hutchinson was produced by the Museum of the African Diaspora on August 29, 2020 as a dramatic reading. The play it was meant to be was waylaid by the circumstance of the Covid pandemic, and truthfully, the Zoom platform didn’t do justice to Hutchinson’s work. But to their credit, the actors’ handling of the script left one longing to see the play fully realized on stage.

Based on the 2015 novel of the same name, White Nights, Black Paradise by Sikivu Hutchinson was produced by the Museum of the African Diaspora on August 29, 2020 as a dramatic reading. The play it was meant to be was waylaid by the circumstance of the Covid pandemic, and truthfully, the Zoom platform didn’t do justice to Hutchinson’s work. But to their credit, the actors’ handling of the script left one longing to see the play fully realized on stage.

This was only one of the hungers the play introduced. Metaphorically, White Nights, Black Paradise feels like a story about hunger and what one might do to have it fed. It attends to what author Sikivu Hutchinson identifies as an erasure of black women in the historical record about Peoples Temple. Although black women made up nearly 50% of the congregation’s membership and the majority of those who died on November 18, 1978, Hutchinson points out their investment in the dream that was Peoples Temple and the storied Jonestown is not proportional. Another hunger—this absence. But what would the women who lived it say? What was their hunger? This is what Hutchinson feeds us.

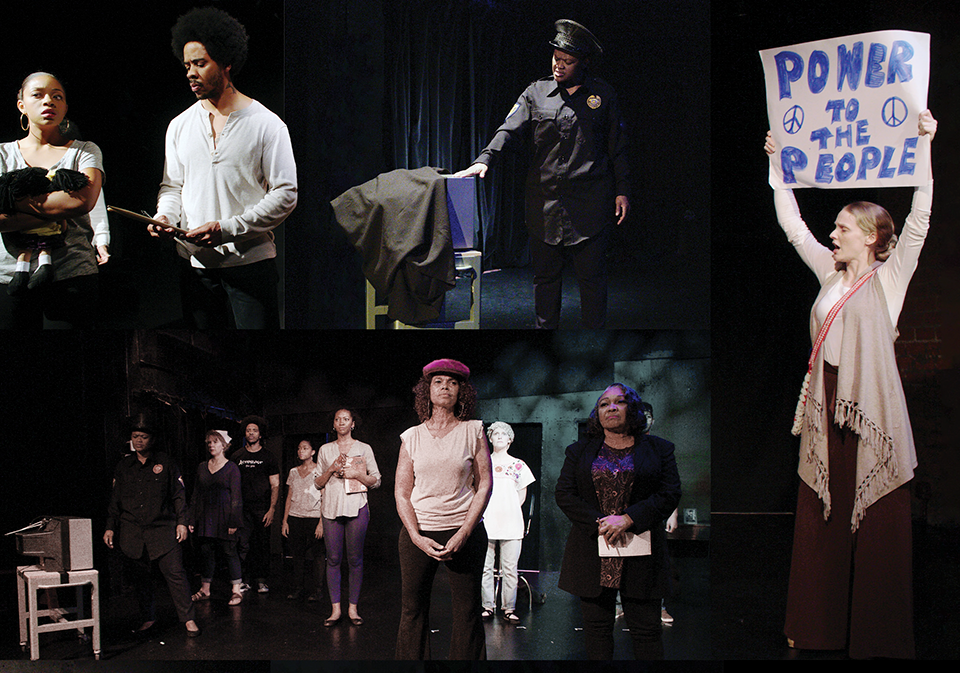

Black women are centered in the play, making up at least that much of the cast. Hutchinson’s efforts to embody and humanize them is palpable and carefully, even tenderly rendered. They are nuanced and imperfect: the women are believers and reluctant cynics and sometimes a little of both; sometimes they are victims and other times victimizers. They are lovers, truth tellers and truth seekers, sisters.

The play opens on the relationship between two sisters, Hy and Taryn, who have recently moved to the Bay Area. Poor and looking for employment they are both hungry—literally and figuratively. Their circumstances inevitably lead them to the Temple where they are lured and held by free meals and eventually, the love and belonging that has eluded them both in the home they left and the new one they claim in the Bay Area.

In fact all, of the black women to whom the viewer is introduced are hungry for un-named but alluded-to community like the sisters, a hunger that is not part of the ambition the West Coast of popular imagination promises to fulfill. Hutchinson’s narrative lays bare the specter of racism and sexism that intersect in these women’s lives, and that inform the ethos of the West Coast, and that illustrates a fuller picture of what might’ve drawn black women to Peoples Temple. She also feeds the viewer’s hunger for an answer to the question: what led black people to the follow a charismatic but still white spiritual leadership? The question-and-answer session that followed the production with Dr. James L. Taylor, Wanda Sabir, the author, and members of the cast provided an informative historical and theoretical outline that the dramatic reading filled and colored.

On offer from Peoples Temple are opportunities to feed the various hungers that are part of this ethos shown byWhite Nights, Black Paradise. For example, the Temple provides solutions to the women’s challenges like lack of affordable housing; the Temple offers communal housing; the Temple solves the issue of limited employment prospects by availing both meaningful work within the Temple and opportunities for work with their community “partners.” Finally, the Temple offers community—all the congregants working, at least in theory, toward a common goal. This is probably the most riveting hunger addressed and its fulfillment proves especially dangerous. Emotional connections tend to tether us as humans; we crave them, find them, gorge on them, and become immobilized. This is what hunger can do.

Each of the sisters find romantic love that binds them to the Temple even when they are most distrustful about the fulfillment of its mission. By the time the women have left the Bay Area to live in the Jonestown community in Guyana, they are attached not only to their romantic partners but to fellow Temple members who we discover sometimes share the skepticism. But there are no plans or means to leave.

What is masterful about Hutchinson’s portrayal of the women even in their lack of plans or means to leave Jonestown, and before that, the deficiencies that lead them to the Temple in the first place, is that the women are not without agency, even in their exploitation. They are women who are aware of the racial and gender-based politics of the Temple and vocalize their awareness. Conversations between the women reveal their awareness that these issues are borne of racism and sexism.

When we first meet Hy, she is recovering from her second abortion in as many years after sex she “enjoyed every minute of.” Taryn lets her lover Jess know, despite the dangers of expressing dissent especially to a lover who is high ranking in the church’s hierarchy, that she is not down for Reverend Jones’ antics. The viewer who is familiar with Peoples Temple knows that the hunger for answers is often filled by the unsubstantial suggestion that black women found their way to the Temple and participated in its demise mindlessly. And to them and certainly uninitiated viewers, these may seem like minor details. But they demonstrate the nuanced view of black women in the Temple that Hutchinson argues is necessary.

Hutchinson’s work is a critical addition to the buffet of material about Peoples Temple offering what black women in Peoples Temple must have hungered for and how the Temple fed those hungers.

(Poet darlene anita scott is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. Her other article for this edition is Marrow: An Origin Story. Her complete collection of writings and poetry for this site may be found here. She can be reached at darleneanitascott@gmail.com.)