(Bonnie Yates is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. Her previous articles may be found here. She may be reached here.)

Even after 42 years have passed, the tragedy that occurred on November 18, 1978, in Jonestown, is well known amongst the modern-day American public, if not around the world. People know that there was a group down in Jonestown that died that day at the urgings of their leader, some people think of it as a murder, but many more see it as an example of a large-scale brainwashing, that when the people were ordered to commit suicide, and that they did what they were told without question. Many individuals in the here and now use the expression, “Drinking the Kool-Aid” when they want to insinuate that someone else isn’t thinking for themselves: whether they know it or not, the origins of that phrase come from the Jonestown tragedy. The name most associated with the jungle settlement, and the deaths that occurred there, is that of the leader of the group, the Reverend Jim Jones. The names of other individuals who played a significant role in what happened that day – chiefly, the decision by Jones that it was time for the membership of Jonestown to “commit suicide” in order to permanently evade the group’s detractors – are rarely mentioned outside of academic circles.

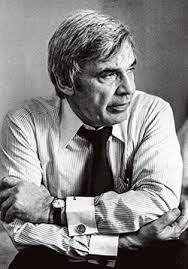

The purpose of this article will be to try to shed some light onto other individuals who, due to their actions or inactions, managed to affect Jim Jones and the membership of Jonestown/Peoples Temple in such a way as to galvanize the final, horrible moments of the 918 people who died that day in Guyana. This article will focus on Congressman Leo Ryan, and how his determination to investigate Jim Jones and Jonestown formed a link in that final chain.

Leo Ryan: His Rise to U.S. Congressman from California, and His Personal Investigative Style Regarding Important Issues

In November 1978, the same year in which the tragedy at Jonestown occurred, Leo Ryan was elected to his fourth term as a U.S. Representative from the 11th Congressional District in California. He had led an interesting life up to that point in time. He had been a submariner in the U.S. Navy during World War II. After the war, he moved to Nebraska and became a high school English and history teacher. Ryan would eventually move to San Mateo County, on the peninsula south of San Francisco, California. In 1956, he made his first foray into politics by winning a seat on the South San Francisco City Council, a position that he held for six years. Then, in 1962, he was elected to the California State Assembly. This was when he made himself known as a maverick fact finder on the issues that affected his constituents.

In November 1978, the same year in which the tragedy at Jonestown occurred, Leo Ryan was elected to his fourth term as a U.S. Representative from the 11th Congressional District in California. He had led an interesting life up to that point in time. He had been a submariner in the U.S. Navy during World War II. After the war, he moved to Nebraska and became a high school English and history teacher. Ryan would eventually move to San Mateo County, on the peninsula south of San Francisco, California. In 1956, he made his first foray into politics by winning a seat on the South San Francisco City Council, a position that he held for six years. Then, in 1962, he was elected to the California State Assembly. This was when he made himself known as a maverick fact finder on the issues that affected his constituents.

His first fact-finding mission came after the Watts riots in 1965: curious about what had caused the racial unrest, he moved in with a black family in the Watts neighborhood, and took a job as a substitute teacher in the community to see what schools and living conditions were truly like. They were less than ideal, to say the least. The schools were disadvantaged in regards to materials, the physical state of the buildings, and the rest of their infrastructure, findings that he reported back to the California State Legislature.

In 1970, as the chairman of an Assembly committee that oversaw prison reform, Ryan decided that the best way to study the conditions of incarceration in California was to experience prison just as a real prisoner would. Using a false name, he had himself admitted to Folsom Prison as an inmate. The experience was overwhelming. The conditions for prisoners were squalid, and upon his return, he reported to his colleagues in the legislature that he had actually feared for his life while behind bars.

In 1970, as the chairman of an Assembly committee that oversaw prison reform, Ryan decided that the best way to study the conditions of incarceration in California was to experience prison just as a real prisoner would. Using a false name, he had himself admitted to Folsom Prison as an inmate. The experience was overwhelming. The conditions for prisoners were squalid, and upon his return, he reported to his colleagues in the legislature that he had actually feared for his life while behind bars.

Critics of Leo Ryan’s Investigative Style

Leo Ryan’s decisions to immerse himself in Watts and Folsom were not universally applauded. Critics described the investigations as nothing more than publicity stunts. Although these critics didn’t necessarily object to his findings, they wondered whether he might get himself or others injured as a result of these missions, or whether he might inadvertently create an entirely different problem by his very presence in these places. What if his incarceration in Folsom had inadvertently led to a prison riot? Would Ryan and/or the State of California be liable for any deaths or injuries? For the most part, Ryan ignored the criticisms: in his view, his missions worked, because they drew public attention to issues which he felt needed to be handled in an urgent fashion.

Ryan didn’t slow down with these crusades with his election to Congress. During his freshman year, he traveled to Newfoundland, Canada, to investigate the clubbing of baby seals for their fur. Ryan didn’t just observe the action. Rather, when he saw hunters approaching a group of baby seals, he lay his body down on the ice to protect the seals. His action not only angered the hunters, but he also succeeded in making himself a nuisance to the people who lived there. Regardless of how he was received, he reported to Congress what he had experienced first-hand, and pressed his colleagues to move quickly on proposals to discourage seal hunting.

It had become a pattern. Leo Ryan was willing to take risks if it meant that there would be swift movement to change situations that he viewed as negative or as a miscarriage of justice. This was the way that he wanted to be viewed by everyone: he wasn’t someone who just sat back, but rather who acted decisively.

His reputation for quick action without necessarily considering the consequences would eventually lead him to decide to go to Jonestown. He just had no idea of how he would be received, or how many lives his decision would cost.

Congressman Ryan Hears about the Allegations against Peoples Temple and Feels a Personal Connection to the Issue

In 1977, with his reputation of being an investigative bulldog proceeding him, Leo Ryan was alerted to allegations of abuse and mistreatment by Rev. Jim Jones and Peoples Temple in the group’s agricultural project in Jonestown, Guyana. His sense of urgency about the matter didn’t truly become intense, though, until November 13, 1977, when San Francisco Examiner reporter Tim Reiterman wrote a story about a Peoples Temple member named Bob Houston who had died under allegedly suspicious circumstances, and whose children’s welfare was uncertain now that their father was gone. Bob Houston’s father, Sammy had been a college roommate of Ryan, and the congressman contacted his old friend to discuss what had happened. Sammy was concerned, not only because of the nature of his son’s death, but of his own inability to contact his two grandchildren living in Jonestown. Ryan found this odd and promised to look into the matter personally.

More information about the Temple would soon emerge. According to Reiterman in his book Raven, “Over the next six to eight months [December of 1977 to July of 1978], Ryan’s interest was aroused further by new developments reported in the press – the custody fight over John Victor Stoen, the defection of former member Debbie Layton-Blakey, [and] the emergence of the Concerned Relatives group” (457).

Formed in October 1977, the Concerned Relatives originally came together through Steven Katsaris, father of Temple member Maria Katsaris, who was part of Jim Jones’ inner leadership circle, both in the U.S. and in Jonestown. Katsaris contacted individuals and families related to Jonestown residents, as well as former members of Peoples Temple who had left the group, suggesting that they meet in order to discuss their common concerns. The group soon formalized its goals: to establish regular communication with family members; to make certain that there were no human rights abuses or horrific living conditions in Jonestown; and to assure that anyone who wanted to leave Jonestown could do so freely. The Concerned Relatives also expressed their misgivings about Jones, wondering whether his mental and physical health could affect their loved ones. Whatever their goals, however, the group was without true leadership until November 1977, when Temple defector Timothy Stoen joined their ranks.

Tim Stoen, Defector from Peoples Temple Wages a Personal War Against Jones

Tim Stoen’s defection from Peoples Temple in June 1977 sent shockwaves through the leadership of the group and devastated Jim Jones. Not just a member of the Temple, Stoen was a lawyer who had worked on behalf of the Temple and its leader on the many legal issues that the group faced. Jones and Stoen had formed a friendship during their time together, and Stoen had become privy to many of the dirty little secrets, both of the group and of Jones himself, especially in regards to how Jones operated. But there was more to the Stoen story than that.

Tim had married his wife Grace in 1972, in a ceremony officiated by Jones, and in January 1972, Grace gave birth to a boy named John Victor. Grace and Tim initially had no issue with their son being raised communally within the group, just as all of the other children were. Almost immediately after John Victor’s birth, though, rumors began to circulate that Tim Stoen was not the boy’s biological father, but that it was Jones himself. The rumors were given credence by an affidavit that Tim Stoen signed to that effect. He had asked Jones to sire John Victor, the affidavit said, because he wanted his child to have a father who was “the most incredible human being to ever exist.” The Temple staff held onto that affidavit, and played along with that story… until Grace defected in 1976. Once Grace left, Jones would tell a very different story: he slept with Grace and got her pregnant, he said, because she was acting as if she wanted to leave the Temple, and sleeping with her was the only thing he could do to “keep her involved in the movement.”

Even though Grace had left the Temple, Tim remained a loyal member, and would be so for another year, and in 1977, he took John Victor down to Jonestown. Grace filed for custody in California courts, but John Victor’s physical presence in Guyana created large complications in the case. Tim left Peoples Temple in June 1977, and by the following November, he would be acting with his former wife in the custody suit. He would also become the leader of the Concerned Relatives.

Congressman Ryan and the Membership of the Concerned Relatives; Pressure Put on Ryan to Act

Leo Ryan set out to speak with everyone in the Concerned Relatives to understand their concerns and complaints, and to address them during his eventual visit to the agricultural project. Not only had his friend Sam Houston asked him to look into the well-being of Sam’s grandchildren in Jonestown, but he learned that the vast majority of the Concerned Relatives members – like Houston – were constituents of his who wanted to know about the welfare of family members in Jonestown. Since Tim Stoen was now the head of the Concerned Relatives, it only made sense that Ryan would contact him. When the congressman met with the group, he learned about John Victor and other custody battles, about the frustrations of despondent family members in reaching their relatives in Jonestown, and about the defectors’ stories of abuse that they had either personally endured or seen others go through under the watchful eye of Jim Jones.

At first, the congressman had thought that members of Peoples Temple were behaving in a manner that he himself had already heard of, but from a different religious group: Scientologists. Ryan had a nephew who had joined Scientology, and who had cut off communication with his family. The Concerned Relatives told Ryan about more than alienation, though: they spoke about physical and mental punishments and abuses under Jones.

Adding to the pressure put on Ryan was a steady stream for requests for Whereabouts and Welfare checks that relatives were putting through to the State Department. From January to November of 1978 alone, there were 27 such official checks requested by stateside relatives, asking that officials of the American Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana, travel to Jonestown and make sure that the person listed was all right. The Embassy did its best to fulfill these requests, but failed to do so as quickly as the relatives wanted them done.

There was a very good reason for that, however.

It was very difficult for consuls from the Embassy to physically get to Jonestown: traveling to the jungle interior of Guyana was a logistical nightmare. Going to Jonestown required an entire day to complete both the trip to Jonestown and the Whereabouts and Welfare Checks, and that was if everything went smoothly. It also required a great deal of advance preparation, from chartering a plane, to requesting access to Jonestown, to ensuring that the individual would be present. It was simply impractical for the American Embassy to send someone to check on the state of an individual in Jonestown every single time that it received a request. As it was, the Embassy did indeed visit Jonestown on a regular basis, usually once every three months. Even the quarterly trips could be difficult to complete, though, if a large rain had come through and made the airstrip or road to Jonestown impassable. Nevertheless, the report from the quarterly visit to Jonestown on January 18, 1978, stated that the Consul had spoken with numerous residents of Jonestown, and had found no one who claimed that he or she was being held against his or her will. For all these reasons, the consul chose to move forward with quarterly visits instead of immediately responding to each individual request.

Further pressure to investigate Jonestown was also put on Ryan by Tim Stoen himself. In that same time period – January to November of 1978 – Stoen spoke often to the State Department regarding John Victor, including eight requests for Whereabout and Welfare checks for John Victor. The State Department sent another three messages to the Embassy inquiring about the progress on the custody battle within Guyanese courts. Eventually, Stoen apparently had had enough. In a cable of October 6, 1978 – approximately six weeks before the deaths in Jonestown – Stoen cabled his threat that “I will retrieve John Victor Stoen by any means necessary.”

Congressman Ryan Formulates a Plan to Visit Jonestown

After having spoken with the members of the Concerned Relatives, Leo Ryan told the group that he would plan on making a trip down to Guyana, but he asked the family members and defectors to keep this knowledge to themselves. Under no circumstances were they to let any members of the press know about the proposed visit. Even Tim Reiterman, who had been following the Peoples Temple saga for The San Francisco Examiner, didn’t know about the trip until it was announced in early November 1978 as part of the announcement of an official congressional inquiry. Reiterman had heard from a member of the Concerned Relatives a few months earlier that “something big was in the air” (476), but that was all that the individual was willing to say. Reiterman went so far as to ask Tim Stoen if he knew of anything in the works regarding Jonestown, but Stoen refused to respond. The Concerned Relatives managed to hold onto the secret until less than two weeks before Ryan’s departure for Guyana.

The Defection of Debbie Layton; Adding Fuel to the Fire that was Jones’ Fear

On May 12, 1978, a haggard looking young woman from Jonestown walked into the American Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana. Debbie Layton Blakey met with American Consul Richard McCoy and begged him to help her return to the U.S. by commercial flight. She didn’t have a passport, she said: it was back in Jonestown, as she was not supposed to be leaving the country on Temple business (or any business, for that matter). McCoy asked her why she wanted to leave Jonestown – where several relatives still remained – whereupon she catalogued the abuses that she had witnessed, the lack of enough food for everyone, and the deplorable living conditions. McCoy requested an affidavit attesting to what she had told him. The most critical aspect of the affidavit that emerged was her statement that she believed that “the loss of John Victor Stoen by Jim Jones would push Jones to force all of Jonestown to commit suicide.”

McCoy gave Debbie a passport and booked her a flight back home. Other Temple members from its Georgetown headquarters tried to dissuade her from leaving – she had been a Temple financial secretary and one of Jones’ most trusted aides – but she rejected the pleas and managed to board her flight home.

Debbie’s defection most definitely had a negative impact on Jones’ mood back in Jonestown. When he learned that she had left, according to Tim Reiterman, he “seriously considered poisoning/shooting all members of Jonestown out of fear. Stephan [Jones’ son who lived in Jonestown as well] managed to talk him out of it” (405). Jim Jones was terrified that Debbie’s exposure of conditions in Jonestown that would cause both the American Embassy in Georgetown and the U.S. government itself to investigate the encampment. This could lead to the end of Jonestown, and Jones knew it. Though independent of the U.S., the Guyanese government certainly wouldn’t risk angering the large and powerful country simply to protect the American expatriates who called Jonestown home. Jones would lose everything that he valued: custody of John Victor, the people who had followed him to Guyana and whose adoration he desperately craved and needed, and the sanctuary from the outside world that Jonestown provided for him (even as it was also becoming his prison). Debbie’s defection was very serious, and what she had told the American Embassy – as well as the press back in the States – represented a real and solid threat.

Despite requesting the affidavit, though, McCoy did not reveal its contents to anyone who should have been made aware of the allegations within it. Instead, he locked the document in an Embassy safe for nearly six months, until early November, shortly before Ryan’s arrival.

After returning home, Debbie took some time to rest and to reconnect with family and friends. She would also reconnect with the Peoples Temple defectors in the Concerned Relatives, and, of course, the leader of the group, Tim Stoen. Debbie gave and signed a second affidavit in June 1978, which was sent to three separate individuals by Jeffrey Haas, the lawyer working on the Stoen’s custody case. The second affidavit was not intended as a stand-alone document detailing what she saw in Jonestown, as the first one did, but rather as ammunition in the Stoen custody battle with Jones. Copies of it were sent to several State Department officials – Douglass Bennett, Jr., Assistant Secretary for Congressional Relations; Ms. Elizabeth Powers in the Office of Consular Affairs; and Stephen Dobrenchuk, Chief Emergency and Protection Service Division, among them – but they later claimed that they didn’t read it because it was attached to correspondence from the Stoen’s lawyer, and they assumed that it was just more information associated with the custody case. Their offices had already been inundated with correspondence from Jeffrey Haas, so this new information was considered just another letter in a series of many and wasn’t given the attention it deserved.

Debbie Gives a Second Affidavit and Tells Her Story to Congressman Ryan

On June 15, The San Francisco Chronicle published an interview with Debbie Layton, conducted by Marshall Kilduff, under the headline “Grim Report from the Jungle.” A few months later, Leo Ryan contacted her and asked for a meeting, which took place on September 1, 1978. As she wrote in her book Seductive Poison, Ryan “admitted that he had several constituents whose children were in Jonestown and that my information corroborated theirs [the constituents] and confirmed his fears” (283). Even though Ryan told Debbie that her story “was hard to believe” (Layton 285), he also said that he was seriously considering leading a delegation to Guyana to investigate Jonestown. In order to bolster his position with his colleagues, Ryan asked Debbie to repeat her story to a congressional committee. She agreed, and testified before Congress on November 9, 1978. Debbie describes herself telling the panel, “The American Embassy was unhelpful… and why, after I had signed my testimony in the consul’s office in Georgetown, hadn’t an official immediately visited Jonestown? They had told me that they would” (287). To say that the officials in the American Embassy – and therefore, the State Department – dropped the ball in regards to forwarding Debbie’s affidavit on to those who should have been made aware of it, is an understatement.

After Debbie’s interview was published, reporter Tim Reiterman began receiving letters from Jonestown residents, accusing Debbie and the Concerned Relatives of “prepping for a mercenary attack on Jonestown” (Reiterman 407). Clearly, Debbie’s defection had done a great deal of damage to the group, but the fact that she had reconnoitered with the Concerned Relatives and Tim Stoen seemed to cause the anxiety regarding an invasion at Jonestown to spiral into a deep fear.

Letters between Congressman Ryan and Jim Jones

Now more determined than ever, Leo Ryan wrote to Jim Jones on November 1, 1978, informing the Temple leader that, after having received numerous requests from his constituents concerning the well-being of their relatives, he was “going to visit Guyana/Jonestown in order to satisfy his constituents.” Although Ryan was quite firm about his upcoming trip, he did ask Jones to send him information about the agricultural project and what sort of work its inhabitants were doing both on site and with the external Guyanese community. The response to Ryan’s letter came on November 6, 1978, not from Jones himself, but from one of the Temple’s lawyers, Mark Lane. The letter had a defensive tone. Lane claimed that the Temple had only heard complaints from “persons hostile to the Peoples Temple” regarding their work in Guyana and on their own land. Lane also informed Ryan that Jonestown was a “private community,” and that the inhabitants who lived there were not required to let anyone come into their settlement. At the same time, the lawyer added, the people of Jonestown would be willing to host Ryan, but that “arrangements must be made in advance” for such a visit. The final subject that Lane touched upon was that two other countries – although not named, it is assumed that he was referring to Cuba and the USSR – had offered refuge to the people of Jonestown, and that it would certainly be an embarrassment to the U.S. if the group were to move to either of the two. This was clearly a veiled threat made in an attempt to make Ryan think twice about his plans.

Ryan was well aware that Lane was trying to intimidate him, and in a second letter, dated November 10, 1978, the congressman went after the Temple lawyer. He “respectfully dissents” from Lane’s allegations that Ryan only wanted to cause Peoples Temple more trouble by visiting Jonestown. He also wanted to make it clear that he wished to communicate directly with Jim Jones, not one of Jones’ lawyers. Ryan firmly reiterated that he was planning to visit Jonestown the following week, and that he intended to speak with those individuals in the Jonestown community whose family members were his constituents. Ryan admitted that he had spoken with the Concerned Relatives and had heard mostly negative things, but, he added, that was why he wanted to visit Jonestown himself. (Although Ryan may have just wanted to be honest in making this disclosure, this affirmation no doubt terrified Jim Jones and his leadership, considering the history between the Temple and the Concerned Relatives). Responding to Lane’s final remark, the congressman stated that the lawyer’s warning of potential embarrassment to the U.S. “does not impress me at all, if the comment is intended as a threat.” Ryan and his investigative committee would “leave as scheduled,” he concluded, to fly to Guyana.

Lane dutifully reported to Jones that the congressman was on his way, and that there was very little that he or anyone else could do to prevent Ryan from showing up at the gates of Jonestown, most likely with a throng of reporters with cameras to document the moment.

Reaction of the people of Jonestown to the impending visit by Congressman Ryan

When Jim Jones informed the residents of Jonestown that Leo Ryan and his entourage would arrive sometime in the next week, they drafted affidavits – many of them dictated by the leadership – and signed a petition of opposition to the visit. The November 9, 1978 statement, signed by hundreds of Jonestown residents, affirmed that there was a “Resolution of the Community” that those who lived in Jonestown “did not invite and do not care” to see Congressman Ryan, the media, or any members of the Concerned Relatives.

About the same time, the residents signed a couple of virtually-identical “Resolution[s] to Block Representative Ryan from Entering Jonestown” – one is dated November 10, the other is undated – which stated that they “will not see or communicate with members of Ryan’s party, Ryan himself, media members or members of the Concerned Relatives who come to Jonestown.” As Lane had noted in his first letter, the resolutions pointed out that Jonestown was the private property of Peoples Temple under Guyanese law, and that the community of Jonestown would “exclude therefrom all persons whose presence is not considered desirable.” The texts also noted that the residents had “requested police assistance from the government of Guyana” in order to keep any unwanted visitors out. The text of the November 10 draft is signed by Paula Adams, a member of Jones’ inner circle, whose loyalty to Jones led her to pursue a sometimes-tumultuous affair with Laurence Mann, Guyana’s ambassador to the United States, in order to stay current on the national government’s thinking about the Temple.

Yet another statement was released on November 13, in which Temple members charged that the Concerned Relatives was a malicious group who had been harassing them for a long time, and that it was now attempting to use Congressman Ryan to further inconvenience them. (I don’t doubt that individuals in the Concerned Relatives were indeed happy that Ryan was taking their concerns seriously; I also don’t doubt that the people living in Jonestown felt that the Concerned Relatives were harassing them). The document noted that Ryan had not agreed to any of the conditions that the people of Jonestown had requested for his visit, such as their demands that the media and members of the Concerned Relatives not accompany him. The statement ends with the proclamation that the community “will request GDF [Guyanese Defense Force] protection from attempts made to enter Jonestown.”

The existence of these affidavits, statements and resolutions plainly show that the people of Jonestown were both angry and afraid of Ryan’s proposed visit. This was a community that had been beset upon by the Concerned Relatives to the point that they felt they were under siege. According to Tim Reiterman, “The Concerned Relatives relentless pressure meant more strategy sessions, and longer hours on the radio transmitting messages [from Jonestown] without adequate sleep or relief from the constant crisis mentality… [M]orale declined” (419). Jones himself was also affected by the never-ending haranguing of the oppositional group, but he clearly wasn’t the only one. Whether it was to learn about their relatives, or to harass Jonestown’s leader, the Concerned Relatives were hurting the inhabitants of the settlement . And there is a deep irony in the fact that they were causing undue stress to the very individuals whom they claimed to care about and whose welfare they wanted affirmed.

Ryan and His Entourage Prepare for their Trip to Guyana, and the State Department’s Failure

As Congressman Ryan and his aides began to assemble a group to travel to Guyana, they chose certain journalists, including Tim Reiterman of The San Francisco Examiner, photo-journalist Greg Robinson, as well as a reporter and crew from NBC. Several members of the Concerned Relatives were also chosen, including Tim and Grace Stoen – whose custody battle for John Victor was still waging – and Steven Katsaris and his son Anthony Katsaris. Maria had charged that her father had molested her in her youth, so it was thought that the presence of her brother Anthony would be seen as less threatening to her.

In the aftermath of November 18, Reiterman would write that at the time that the congressman put together his entourage, “the State Department spent most of their time subtly discouraging Ryan [from making the trip] by talking about transportation difficulties and so on, while neglecting to provide crucial information – the apparent psychological state of Jim Jones” (460). The State Department further tried to dissuade Ryan by telling him that Jonestown was private property. According to Reiterman, “Representative Ryan had… ignored warnings and plunged ahead… despite the Temple’s discouraging letters” which Ryan had received from Mark Lane (481). Although Ryan had tried to calm the fears of others about going with him by telling him that they were “protected by his Congressional Shield” against any sort of attack, he was also “counting on the news media to help him get into Jonestown and to bring out anyone who wanted to leave… In a way, he viewed the Press as a key element in forcing out the truth about Jonestown and as protection; the glare of publicity might inhibit any Temple inclinations to cause trouble.”

At least, that was Ryan’s thinking. The State Department, however, knew more about the mental state of Jim Jones, his inner circle, and the general populace of Jonestown, but they failed to mention any of that to Ryan.

Perhaps, if the congressman had been privileged to the State Department information, he would have decided to hold off on his trip. Or perhaps he would have done it anyway, understanding that this fact-finding mission was indeed simply a publicity stunt. It’s reasonable to assume that Ryan expected to gain entry into Jonestown, just as he had requested, and be allowed to interact with the people there. It’s also just as reasonable to assume that Ryan traveled to Jonestown anticipating that he would be denied entrance at the gate, which the news cameramen would dutifully document. Ryan could then return to the U.S. safely and use the lack of access into Jonestown to pressure other Representatives to work with him for deeper investigations into Jonestown. (This writer would argue that the latter was far more in line with Ryan’s way of handling issues, and also far more logical of an assumption for Ryan and others to make, considering the strong resistance to a congressional visit that the people of the settlement had shown up to that point). Is it possible that Ryan, expecting to be denied entry, was unprepared to deal with the reality inside of Jonestown, especially in regards to Jones’ mental and physical health, and without knowing exactly how conditioned the inhabitants were to the possibility of committing mass suicide? That’s a question for another time.

Jones’ Mental State and how it Affected the Congressional Group’s Visit in Jonestown

Jim Jones did not mince his words with reporters. He looked tired and physically unwell, and was so nervous when he spoke, that it was obvious that his mouth was dry. “He spoke of himself as a prisoner,” Tim Reiterman later wrote. “He said that he needed the medical treatment ordered by Dr. Goodlett [his physician], but he could not leave Jonestown for fear John Victor Stoen would be kidnapped, for fear things would collapse in his absence” (497). Indeed, Jones had not left Jonestown even once in the 18 months since he had arrived. A Guyanese court had ordered him to travel to Georgetown and “present” John Victor so that the case could move forward, but Jones had refused to comply. At that point, the judge had issued an arrest warrant for Jones, but the sentinels at the community’s front gate had refused to physically touch the warrant. It was then nailed to the gate. From that moment onward, Jones believed he could not leave the confines of Jonestown without having to worry both about being arrested and kept away from his people, and about John Victor being kidnapped and brought to Georgetown, where a judge might very well take the child away from him. It was a risk that Jones simply couldn’t take.

Investigations into the Failure of Ryan’s Trip to Jonestown – The Crimmins Report

In the aftermath of Congressman Ryan’s trip, with 914 members of Peoples Temple dead, and Congressman Leo Ryan and three members of the media shot to death at the Port Kaituma airstrip (another nine individuals were wounded at the airstrip, but survived their wounds), the State Department and the American Embassy found themselves under the microscope. There were many who believed that the State Department and Embassy had failed in their jobs to give Congressman Ryan and his delegation all of the information they had on the behavior and psychology of the people who lived in Jonestown. State hired two retired Foreign Service Officers to investigate their actions. The Crimmins Report was published in May 1979, roughly six months after the tragedy. According to Rebecca Moore in her book, A Sympathetic History of Peoples Temple and Jonestown:

[The Crimmins Report] studied two main areas of State Department involvement. The first covered the relationship between the Temple and the Concerned Relatives. Both the department in Washington, D.C., and the Embassy in Georgetown viewed the conflict between the two – particularly in the dispute over the custody of John Victor Stoen – as a fight between two groups of Americans (368).

Because of that, the State Department and the Embassy decided not to get more directly involved, especially since they needed to be seen as impartial in the custody dispute. Indeed, in an effort to appear as impartial as possible to the two sides, they did not let Leo Ryan know that, “[t]he custody case came to be the primary focus of the State Department and Embassy… Overall, it consumed considerably more than half the total time and effort devoted by officials to the entire array of questions revolving around the Peoples Temple” (Crimmins 27).

There is no doubt that Ryan and his aides were not made aware of exactly how contentious the custody battle was between the Stoens and Jim Jones. That lack of information undoubtedly affected the congressman’s trip to Guyana, as well as how the trip was interpreted by Jonestown residents. Indeed, although they were not chosen to accompany Ryan and his group to Port Kaituma, it is important to realize that both Tim and Grace Stoen made the trip to Guyana along with his delegation, and stayed behind in the Pegasus Hotel while Ryan’s group made its trip to Port Kaituma.

In her assessment of the Crimmins Report, Moore continues, “The second area of the State Department’s responsibility in regards to Peoples Temple encompassed the preparation and handling of Leo Ryan’s visit to Jonestown. In this respect… The Crimmins report authors felt ‘the briefings for the Congressional visit were quite thorough in content and scope.’” Ryan’s aides disagreed with this interpretation, and “pointed out that the State Department made very few, if any, cables or documents available to them” (368). As it turned out, the State Department had information files on 912 members of Peoples Temple, but they didn’t offer any of them to Ryan or his staff.

The Crimmins Report concluded that Congressman Ryan was not given a warning about the possibility of the inhabitants of Jonestown being violent, and that this was simply because the Embassy officials never experienced any behavior that would lead them to draw that conclusion. However, we know this is not so because of what Debbie Layton swore to in her affidavits. The problem was that Embassy Consul Richard McCoy and State Department officials in Washington didn’t take the suggestions of a possible mass suicide seriously, whether from Debbie or anyone else. When Temple member Sharon Amos, who managed the Temple headquarters in Georgetown, specifically told McCoy that Jim Jones and the people of Jonestown “would die before they would give up custody of John Victor Stoen,” he ignored her statement. The willful disregard, based upon its policy of trying to appear impartial to the two parties involved, is even more baffling, especially when fully half of the cables between Georgetown and Washington in the first ten months of 1978 reported on the increasing tension over the Stoen custody case. As Moore notes, “The Crimmins Report really doesn’t analyze why the State Department ignored the suicide threats. In fact, its omissions reveal more than its contents” (369).

It is this writer’s belief that the Crimmins Report fails to explain why the suicide threats were dismissed because there is no tenable position that State Department or Embassy officials could take. Suicide refers to an individual who has caused his or her own death. Suicidal individuals are more prone not just to hurting themselves, but to hurting others, if that’s what it takes to complete the act. These threats alone should have been enough to give officials pause. The fact that they didn’t inform Ryan or his aides about the threats of mass suicide show an unconscionable lack of concern for others, and a dereliction of duty to ensure the safety of Ryan and his entourage during his visit to Jonestown.

The Crimmins Report noted:

The single most important substantive failure in the performance of the Department and the Embassy was the aborted effort by the Embassy to obtain authorization for an approach to the Guyanese Government. Although the June [1978] exchange of telegrams was mishandled at both ends, the decision of the Ambassador not to pursue the issue was ultimately critical. (94).

Other than criticizing the handling of the telegrams, the Crimmins Report ascribed very little blame for the mishandling of the Ryan trip to State or the Embassy, although Ambassador John Burke did receive a bit of a rebuke. Burke had the primary responsibility for alerting Congressman Ryan to any possible issues with his trip to Jonestown, the report found. And as Moore noted, the authors of the report felt that “[i]f Burke felt strongly about Jonestown… he should have protested State’s inaction on his request to approach the Guyana government. He did not” (372).

So why didn’t the State Department tell Ryan what it knew? Why, to the contrary, did the agency come up with ways to avoid sharing that information. The Crimmins Report lays out its thought process: State couldn’t give information to Ryan “because it would violate the Privacy Act.” The Freedom of Information Act was also blamed for “crippling” communication between State and Ryan, since the agency didn’t want its relations with Jonestown revealed to the public as a result as an FOIA request. Finally – and perhaps most curiously of all – the State Department claimed to be concerned about the First Amendment rights of the Temple, which the agency claimed would be violated with release of its information about Jonestown.

The State Department was too busy worrying about the privacy rights of those people who lived in Jonestown, the Crimmins Report found, and recommended that Congress amend the Privacy Act in order to prevent such a tragedy from happening again. However, according to Moore, “if Embassy officials knew, or suspected, something was wrong in Jonestown, neither the Privacy Act nor the Freedom of Information Act, nor the First Amendment prevented them from acting responsibly” (370).

Hindsight – Analysis of Ryan’s Trip and what Went Wrong

Hindsight – Analysis of Ryan’s Trip and what Went Wrong

In its November 2019 edition, CQ Magazine focused on the Jonestown tragedy some forty-one years earlier, with articles describing the mistakes that were made by the State Department and Embassy, the “What Ifs” that came from introspection on the Peoples Temple question, and an in-depth look at Congressman Ryan’s reasons for going to Jonestown.

Writing about how the State Department failed to act in regards to warning Ryan and his delegation about possible risks in traveling to Jonestown, lead author Mark Stricherz noted,

…a CQ Roll Call review of thousands of pages of testimony, diplomatic cables, letters, affidavits and federal investigative reports reveals how State Department officials for more than a year muffled their own suspicions, discounted appeals for help, and neglected to elevate reports about serious allegations of abuse to senior diplomatic officials.

In other words, it’s extremely clear, from looking at the vast array of sources in the State Department files in 1978, that Embassy officials – including Consul McCoy and Ambassador Burke – were well aware of the severity of the accusations being made against Jones and the Temple leadership. Nevertheless, no one bothered to make State aware. This writer believes that knowledge of these accusations would have no doubt altered how Congressman Ryan and his aides conducted their investigation of Jonestown. Of course, there’s no guarantee that knowledge of these threats would or could have prevented the tragedy, but the reality is that neither the Embassy nor the State Department passed along the plethora of information to Ryan and his entourage.

Another example of an Embassy misstep comes comes from a conversation that Consul Richard McCoy had with Grace Stoen during her trip to Guyana in the fall of 1977 – a year before the tragedy – to pursue her custody case. “If anyone else defects and corroborates her [Grace’s] stories” of abuse in Jonestown, McCoy promised her “the U.S. would take action and open an investigation into Jim Jones/Peoples Temple/Jonestown” (Stricherz 21). We know that there were numerous people who left Jonestown before November 18, 1978 – Debbie Layton, Yulanda Crawford, and Tim Stoen among them – all of whom either wrote affidavits or letters to Congress, or spoke to the press. Grace’s claims were that there was physical and emotional abuse going on in Jonestown, but there was no official investigation of the charges. What’s even more sickening about McCoy’s promise to Grace Stoen is that, as the American Consul, it was up to him to investigate these matters as far as he could go, before handing his information up the chain of command. The question we’re left with is, did McCoy ever mean to keep his promise? Did he and other Embassy officials intend to look further into matters, or were they merely trying to placate people and get them off of their backs? In the case of Debbie Layton, the Embassy and Ambassador Burke had already made a decision. “They ruled out going to Federal investigators [after Layton gave her affidavit], believing that Layton should take the initiative herself [back in the U.S.)]” (Stricherz 23).

What’s more baffling is that Richard McCoy had been on the same flight as Debbie was when she flew back to the U.S. She asked him repeatedly what the next step was, if she should contact the police, etc., but he gave her no direction about what she should do. So Debbie did nothing until she gave her second affidavit in June of 1978. If Ryan hadn’t seen the newspaper interview that she gave to publicize it, he might not have even known that she was a source of information for him.

Stricherz ends his article with a powerful statement on how the inaction of the Embassy and State Department further crippled Ryan’s knowledge of what he would be facing in Jonestown. “Without the benefit of cables or reports, Ryan and his team were unaware that the State Department hadn’t followed up on Layton’s allegations” (25). Informing Ryan that Layton’s statements had not been discounted was a serious error in judgment: without directly telling Ryan, and with Ryan believing that the State Department and Embassy were doing their jobs investigating Debbie’s charges, it’s safe to say that the congressman assumed that the charges had been found to be false. It may have been a false assumption on the congressman’s part, but considering how quickly the delegation was trying to move forward with their trip, it might have also just slipped through the cracks that there wasn’t a report denying the claims, either.

In an interview which also appeared in the November 2019 edition of CQ Magazine, Danny Coulson, former Commander of the FBI’s Hostage Rescue Team, spoke with writers Shawn Zeller and Marcia Myers about what had happened in Jonestown. Coulson was clear that the combined affidavits of Debbie Blakey and Yulanda Crawford were more than enough to warrant an investigation. But, as Coulson suggested as the best way to handle Jonestown would have been at that point, “It’s also possible to speculate that, with the benefit of hindsight, the way to avert the 918 deaths in Guyana was to have left Jim Jones and his followers alone… You don’t start a direct confrontation… That plays into their sermon. Their way of getting into heaven is to die in a fiery battle” (29). Although the group in Jonestown wasn’t looking to get into heaven, but instead had the goal of “making a mark for socialism,” it is indeed true that Jones was waiting for something to be a catalyst for the mass suicide.

No doubt, Ryan would’ve disagreed with that statement, as it wasn’t his normal modus operandi to leave things be. Ryan wanted both his constituents and the general public to see what he was doing and what results he was striving for. But his visit to Jonestown – especially if he left with a handful of members – was more than enough of a catalyst to push Jones over the edge. Once Temple gunmen returned from the Port Kaituma airstrip and announced that they had killed Congressman Ryan and others, Jones had the perfect narrative. There was no going back, he told his people, the congressman had been killed, and now outside forces would be coming for them. The decision to die was one of self-defense so that they wouldn’t be tortured. Simply put, Ryan’s visit gave Jones exactly what he needed to complete what he had seen as inevitable. As Coulson summarized it, “Ryan, accompanied by nine journalists and four Concerned Relatives, was a catalyst for Jones’ paranoia… Jones was looking for an excuse… [the visit by Ryan] probably triggered it” (29).

A second article by Mark Stricherz for CQ Magazine further evaluating Ryan’s trip opens with a quote by Stuart Wright, a Professor of Sociology at Lamar University: “Leo Ryan was the wrong person to go down there because he’d aligned with the Concerned Relatives.” U.S. Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif) – who in 1978 was working as an aide for Rep. Don Edwards, a contemporary of Ryan’s – agreed. “I wish Leo had not gone. I think it [Ryan’s decision to travel to Jonestown] was a mis-reading of the situation.” There is a great deal of truth to these statements. Ryan hadn’t personally spoken to Jones or anyone in Peoples Temple prior to his visit to Jonestown, but the Concerned Relatives group had been telling him their stories for months. At no point during those discussions was the Temple’s point of view offered to Ryan; he only heard the one side of the story. In reality, then, Ryan’s desire to investigate the settlement came from a point of undue bias that favored the Concerned Relatives and not the people of Jonestown.

Jackie Speier, Ryan’s aide who accompanied him to Jonestown and who herself was severely wounded during the attack at the Port Kaituma airstrip, has never criticized her boss’ decision to go to Guyana. Instead, Speier – who is now a U.S. Representative in her own right – places the blame for the mistakes on the State Department and the U.S. Embassy. Quoted in Stricherz’s second article, Speier said, “The State Department did not do its job – it had a duty to warn, it had a duty to investigate and it had a duty to protect, and it failed on all three of those [duties)” (Stricherz 31). Despite all these missteps – the errors of omission and commission by numerous parties – there was no real reason to rush to Guyana so abruptly. Ryan could have just as easily done more to try to speak with Jim Jones directly, if not initially with the people themselves, to better familiarize himself with the Temple and to consider its reaction to charges by the Concerned Relatives and other Temple opponents.

He didn’t. Nor did he heed any warnings given to him in the weeks before his departure and once he got to Guyana – he even apparently disregarded the statement that he would be considered another American citizen in Guyana, once he was on Guyanese soil – but rather decided to push forward. In the end, his lack of preparation would contribute to his ultimate downfall, and to the 918 lives lost due to his lack of foresight.

In the Aftermath of the Tragedy at Jonestown

The effect of the tragedy of Jonestown, and the failure of Leo Ryan to realize what he was up against, would change the way that government agencies interacted with groups, religious or not, that isolated themselves away from the general public. This became especially true for any incident in which a group considered hostile or violent was believed to have weapons, or was thought to have individuals who could be used as hostages, including children living in the group.

In 1977, the year before the Jonestown tragedy, FBI Agent John Douglas began working in the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit (BSU), where he taught the skill of hostage negotiation and created the forensic science that today we call Criminal Profiling. Criminal Profiling is most famous as a remarkable and powerful investigative tool to help investigators create a profile of an anonymous serial killer. This profile helps in narrowing down lists of suspects. It is now commonplace to amass as much information as possible about a potentially hostile individual or group before any government agency attempts to make an initial contact. Such profiles can be made on any individual, and this writer cannot help but to believe that a Criminal Profile on Jim Jones would have been extremely helpful to both Congressman Ryan and any investigative body that was looking at the Temple leader for possible illegal activities. However, at the time that he began to create Criminal Profiles, Agent Douglas wasn’t taken seriously by his superiors. Years later, with the addition of the Criminal Profile to the mix, the FBI has been able to handle hostage negotiations much better. But in 1978, no governmental agency was prepared for the kind of situation that Jonestown presented.

Discussion and Conclusion

By all accounts, Leo Ryan was a caring man who genuinely wanted to improve the lives of his constituents, and to help them when they needed the aid of a government official. His fact-finding missions served his own purposes, by getting himself and the issues he cared about in the media. However, his brash methods of investigation and the dangers that such actions posed for both himself and others eventually caught up to him in a way that he couldn’t have foreseen. After all, each of his previous fact-finding missions had worked to his advantage. Why would he think that his venture to Jonestown would be more dangerous than anything else?

However, there must have been something that told Ryan that this foray to Jonestown wasn’t like anything else. Certainly his aides knew there might be danger in the Guyana jungle: both Ryan aide Jackie Speier and House committee aide Jim Schollaert made out their wills before they left for Jonestown.

On the other hand, there were suggestions that might have led Ryan to think that he wouldn’t be in any real danger by making the trip. After all, Peoples Temple attorney Mark Lane had told him that Jones would not allow the congressional entourage into the community if it included the press or members of the Concerned Relatives. However, Ryan made certain to bring the reporters and two Concerned Relatives with him on his flight to the airstrip at Port Kaituma, along with U.S. Embassy Consul Richard Dwyer, Guyana government information officer Neville Annibourne, and two Temple attorneys, Mark Lane and Charles Garry. Under some interpretations of Ryan’s actions, there is reason to believe that he thought his group would not get past Jonestown’s front gate. In that case, he would stand at the entrance, confronted by Temple sentinels and being denied access, while cameras and reporters documented every second of it. After all, it was Ryan’s style to go for the headline and get a splashy story that would pressure Congress to take action on his issue. It would also explain why he didn’t make more of an effort to learn a fuller picture of Jim Jones as a person, and of Peoples Temple as a group: he didn’t think he would need that information, because he didn’t expect to be allowed into Jonestown. In addition, under that scenario, when Ryan’s bluff was called – when the Jonestown leadership in fact opened its gate – Ryan would have found himself unprepared for the interactions he was about to have with the Jonestown community. And that would have been just as much of a fatal error as any other action he had taken – or hadn’t taken – in his fact-finding mission.

This scenario begs the horrible question: Did 918 people die because of a Ryan-led publicity stunt gone wrong? In the final analysis, this is possibly the most viable explanation as any other for Ryan’s reliance upon a single source of information about Peoples Temple – the Concerned Relatives and other defectors – his lack of deep knowledge about his potential adversary, and his willingness to disregard warnings about his safety.

One cannot fail to recognize the impact that the Concerned Relatives had on Ryan to investigate Peoples Temple, and vice versa. A year before Jonestown, the Concerned Relatives was a small, still-ineffective group which had managed to attract some press coverage and recognition on the part of some policymakers of their existence. But they were nothing like Peoples Temple and Jonestown. So, when Congressman Ryan contacted them to hear their stories, they were ecstatic. The fact that they had a sympathetic ear in someone who had the power to act, who could encourage other agencies of local and federal government to act, was something that they had dreamed of since the group’s inception.

And they succeeded. The amount of pressure that the Concerned Relatives – and especially Tim Stoen – put on Leo Ryan, manipulated him to such a degree that he lost his objectivity about what he could do and how he could do it. Because of who he was, he had no other choice but to act on the issue.

With more than forty years passed now, and with hindsight making certain aspects of the situation now clear, it is obvious that Congressman Leo Ryan truly was the wrong person to go to Jonestown. What was going on between the two forces of opposition in Peoples Temple and the Concerned Relatives, wasn’t a basic disagreement; it was a game being played for keeps.

We can never know whether the deaths in Jonestown would not have occurred under other circumstances, that is, if Ryan had not decided to go to Guyana. We do know, however, that Jones was physically sick and – according to his own physician – didn’t have much longer to live. If Jones was going to persuade everyone else to die too, he was going to need a good reason, something he could use to convince his followers that there was no other way out.

The brashness and arrogance of Leo Ryan would suit his purposes just fine.

Works Cited

The Performance of the Department of State and the American Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana in the People’s Temple Case (The Crimmins Report), U.S. Department of State, Washington, D.C., May, 1979.

Layton, Deborah. Seductive Poison: A Jonestown Survivor’s Story of Life and Death in the Peoples Temple. New York: Anchor Books, 1998.

Moore, Rebecca. A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in the Peoples Temple. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1985.

Reiterman, Tim with John Jacobs. Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People. New York: Dutton, 1982.

Stoen, Timothy Oliver. Marked For Death: My War With Jim Jones the Devil of Jonestown. North Charleston, South Carolina: CreativeSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015.

The State Department Cables (1978 Jan-Nov)

Stricherz, Mark. “A Congressman’s Quest for Truth.” CQ Roll Call Magazine. November 18, 2019.

Stricherz, Mark, ”Jonestown: How the State Department Dismissed Red Flags Leading up to a Horrific Mass Murder in 1978.” CQ Roll Call Magazine. November 18. 2019.

Zeller, Shawn and Marcia Myers. “Haunted by ‘What-ifs’.” CQ Roll Call Magazine. November 18, 2019.