(Editor’s note: This review of Sikivu Hutchinson’s play was published in the October 28, 2020 edition of The San Francisco Bay View, a Black newspaper, and is reprinted with permission of the author. The original article may be accessed here.

I attended a remarkable and enlightening play reading and discussion at MoAD Aug. 29, 2020. Dr. James L. Taylor is such an erudite man and was so in his element as an expert on the history of San Francisco.

I attended a remarkable and enlightening play reading and discussion at MoAD Aug. 29, 2020. Dr. James L. Taylor is such an erudite man and was so in his element as an expert on the history of San Francisco.

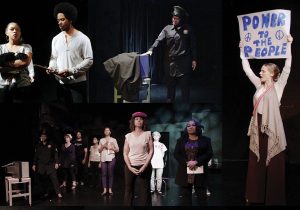

With notes in hand, he and playwright Sikivu Hutchinson, Ph.D., unpacked together with audience and cast members the phenomenon of Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple in the play “White Nights, Black Paradise.” The play looks at the perils of displacement and how when one feels as if she has nowhere to go and does not belong anywhere, kindness can be her undoing.

Jim Jones and his agents handpicked vulnerable people and took their wealth, promising care. Later, when funding ceased and the church lost its property, the vision was a new colony called “Jonestown,” in Guyana.

The massive out-migration into the jungles of Guyana was celebrated by some members, while others looked on with suspicion. Some families and friends tried to discourage the move.

Once in Guyana, people starved to death. [Editor’s note: The managers of this website are not aware of any deaths by starvation.] It was not the utopia promised. A few people got away; however, most participated in the mass genocide, where over 900 people were forced to drink the literal kool-aid at gunpoint.

Once in Guyana, people starved to death. [Editor’s note: The managers of this website are not aware of any deaths by starvation.] It was not the utopia promised. A few people got away; however, most participated in the mass genocide, where over 900 people were forced to drink the literal kool-aid at gunpoint.

What circumstances or conditions led to the massive homelessness and psychic, almost psychotic, instability? How did Jones get almost 1,000 Black people – a majority of whom were women, children and elders – to leave without protest? What was going on in San Francisco, in urban America and the West Coast that would make this antichrist get religious and political leaders to give him their blessing?

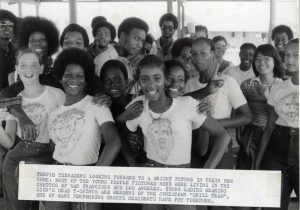

My friend, Sister Maryom Ana Al Wadi, a leading pioneer in the Black student movement at San Francisco State University – which established the first Black Student Union on an American campus and led to the resulting broader student movement establishing Black Studies courses and Black Studies programs at American institutions of higher education – told me that at that time, people were looking for answers and a place of refuge, and they found such at Peoples Temple.

Some people found answers in the Nation of Islam, located just next door to Peoples Temple, where Sister Maryom and I were members, while others found political agency in the Black Power Movement which was winding down, yet not fast enough for municipalities wanting to silence Black populations.

During this period in the Bay Area and in the country, Black folks were standing up, similar to now in the Movement for Black Lives. Black people were sick and tired of legislated violence. Watts (Aug. 11-16, 1965) in LA kicked off the revolt in California, followed by an uprising the night of Sept. 27, 1966, when policeman Alvin Johnson killed Matthew “Peanut” Johnson, a teenager, as he ran away from a stolen car. Fifty-one people were injured.

However, the country was burning from coast to coast – Kerner Report notwithstanding. Everyone with the power to stop the unrest did nothing except move up the bulldozing. This retaliation, headed by officials in the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, started pushing Black folks out of the Fillmore – among the casualties was Peoples Temple property, where members lived communally, with all their physical and psychosocial needs taken care of.

When the church lost its real estate, one would see people outside the building on Geary Boulevard begging. Sister Maryom said it was so sad, she’d walk around the block and come up Fillmore to attend the meetings at Mosque 26 on the corner.

For African Diaspora people living in the Fillmore and kicked out of their housing, a majority of whom were unhoused or incarcerated, hungry and unemployed, Peoples Temple was a refuge.

It was a place where people belonged. It was almost too good to be true, and, as many sadly learned too late – it was. Once urban renewal, or Black removal, was complete, Jones took his people to Guyana, a situation worse than anything people could imagine in San Francisco, worse than what they’d left – but the exit or stamped ticket read “one way.” Once in Guyana, people were stuck.

There are not many books that look at Peoples Temple through the lens of Black women. Not only does Hutchinson’s work spend the majority of time in the heads of Black women characters, she also makes these characters complex, adding a layer of sexual violence to the discourse as reason for much of the irrational belief in this man even when his sanity was called into question.

Thoroughly researched are the parallels between Jonestown and Hurricane Katrina – and now Hurricane Laura in Lake Charles, where people are not able to leave, according to Rev. Lennox Yearwood Jr., president and founder of Hip Hop Caucus, in an interview with Davey D on Hard Knock Radio.

What is it about Black bodies moving that generates so much fear? Is this fear a projection? If I had the horrific reputation white America has for Black Americans, I’d be nervous too.

These Black women members of Peoples Temple whom we come to care about are also vulnerable. They swim into deeper waters, unaware that the temperature is getting hotter, until they are cooked. Is Black America cooked? Is the current state one where ovens are preheated and we just tolerate the heat until we can turn it off or become consumed?

We have a similar situation now, except African nations are telling African Americans to come home – so far, there is no economic investment tied to this invitation as it was following the devastating earthquake 10 years ago, when President Abdoulaye Wade welcomed 163 Haitian students to Senegal to finish school there, an invitation that covered tuition fees, room and board, paid for by the government. We have options, if we can get there. I’d like something a bit more concrete.

If Africa is for Africans, after the numbers stop peaking in California, now might be a good time to make a move, especially if these African nations provide a bit of support. With the coronavirus numbers rising and the economic situation worsening for many people, a fresh start in the land of our ancestors might be just the thing to heal the ever-present persistent trauma that keeps Black people from realizing their full human potential.

We say no more Jonestown, but with the massive internal displacement normalized today, who’s to say?

Everything changed in the ’60s Black Fire. Then and now – there is a race war. We have to pay attention and think for ourselves, Sister Maryom told me. “Fear conditioning is really powerful. Free labor allows us to belong wherever we choose to be.” In other words: Don’t believe the lie(s).

(Bay View Arts and Culture Editor Wanda Sabir can be reached at wanda@wandaspicks.com. Visit her website at www.wandaspicks.com throughout the month for updates to Wanda’s Picks, her blog, photos and Wanda’s Picks Radio. Her shows are streamed live Wednesdays and Fridays at 8 a.m., can be heard by phone at 347-237-4610 and are archived at http://www.blogtalkradio.com/wandas-picks.)