Theological interactions are always personal interactions, and personal interactions are always theological interactions. Thus is the nature of being human. We reflect on what is, in order to ponder what was or what might be. Words run together. Words run apart. Nothing is clear. Everything is clear. Thus is the nature of running into God.

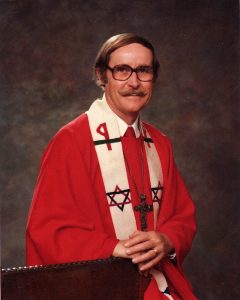

Few collections of words reflect the truth of such thoughts more than the sermon that Rev. John Moore delivered at the First Methodist Church of Reno, Nevada on November 26, 1978. Eight days prior, two of Moore’s daughters, Carolyn and Annie, and his grandson Kimo died in the mass suicide/murder that transpired in Jonestown.

Few collections of words reflect the truth of such thoughts more than the sermon that Rev. John Moore delivered at the First Methodist Church of Reno, Nevada on November 26, 1978. Eight days prior, two of Moore’s daughters, Carolyn and Annie, and his grandson Kimo died in the mass suicide/murder that transpired in Jonestown.

Truth be told, his daughters were more than just victims. They were also perpetrators, having been part of the mechanism that made the suicides/murders happen. I have no doubt that Moore knew that there was more to the story than just the deaths, that his daughters were too high up in leadership of the community and too enamored with Jim Jones, not to have been part of what had taken place. No doubt, these were confusing days. Yet, Moore still proclaimed what he knew to proclaim, the personal and the theological, the theological and the personal, the divinity of the human, and the human of the divinity.

Barbara and I were on a retreat last Sunday when I was called out of a meeting. I returned my sister’s phone call and was told of the assassination of Congressman Ryan and the others. Mike and Foofie Faulstich brought us home. On the way, Mike said: “John, this is your calling.” I knew what he was talking about.

We have been called to bear witness to the word God speaks to us now. I say “We,” because you are as much a part of this as I am. There is no witness to the Word apart from the hearing of it.

Barbara and I are here by the love and strength of God which we have received through your caring and your prayers. I never imagined such a personal blow, but neither could I have imagined the strength that has come to us. We are being given strength now to be faithful to our calling.

Moore spoke from the cross that day. I’m not talking about a theoretical cross, I am talking about the actual cross, the very place where Jesus died. Dangling, somewhere in hopeful disbelief of the “love and strength of God.” Intermittently, swinging between loved and forsaken. “My God!! My God!!” In those moments, Moore invites us on the cross. Only the foolish would go. Yet, perhaps that is exactly what love is.

So I stand. The Word is not separate from the words of Moore. I feel them calling my name. I’m not sure I believe in prayer as much as Moore did, but I want to. I desire to believe that whispers of others could get me through such a moment. Only on a few occasions have I known a slight glimmer of Moore’s strengths. They were similar times of tragedy. I guess that’s when people were praying for me too.

I am a sponge. If my voice breaks or there is a long pause, I want you to know that it’s all right. I am preaching this morning, because we alone can make our unique witness, and today is the day to make it.

“If my voice breaks…” How in the hell could the voice of Moore not break when he had been dealt such pain? “My God!! My God!!” Moore knew that this was his cross to carry. Moore knew that this was his place of crucifixion. Moore knew that there had to be more than this. Moore stayed upon that cross, “faithful to his calling,” and the people cried out, “remember me when you enter the realm of God.” Few had dared journey to such a space before. These were his damn daughters. This was his grandson. Everything was dead, and Moore was dying.

Following the sermon, we shall join in prayers of intercession for all of the people involved in this tragedy, from those first shot down to all who died, and all who grieve.

During these past days, we have been asked frequently: “How did your children become involved in Peoples Temple?”

In Moore’s first indication that something more might have happened than a bunch of altruistic suicides, he encourages his audience to pray for those who had been “shot down.” Surely, in the midst of such a statement, Moore was aware of who the shooters might have been. Yet, from the cross, Moore still offers prayers for the murderers, knowing that salvation can only be found in an ability to find forgiveness for the worst of these as much as one finds forgiveness for the least of these. Surely, the cross was also for Jonestown’s death row. Surely, Moore could see them all from his cross.

There is no simple answer. We are given our genetic ancestry. We are given our families. We are all on our personal journeys. All of these, along with the history of the race, converge upon the present wherein we make choices. Through all of this providence is working silently and unceasingly to bring creation to wholeness.

Many people thought that Jesus was crazy for not removing himself from the cross. “If you are, then get your own ass down.” Moore could hear the taunts. Moore knew the pain of the questions. Moore chose to remain. Moore chose to offer the path of “creation to wholeness” as something more than just “living and dying.” Moore chose to offer the path of “believing and doing” to a skeptical people. You see, Moore raised his children to be doers, and doers often die doing. Moore refused to get down from his cross.

I will talk only of our children’s personal histories. The only way you can understand our children is to know something of our family. In our family, you can see the relationship between the events of the sixties and this tragedy, just as there is a relationship between the self-immolation of some Americans during those years and the mass murder-suicide of last week.

The revolutionary suicide of Jesus pops up in Moore’s ponderances of the suicides of Jonestown. I believe him with all my heart. I know that my life will never be a life unless it goes through the cross. I hear Moore calling me forward. But not so fast. In his descriptions of his children, Moore reminds us that there are things worth holding on to. There are people at the foot of the cross worth looking at a little longer before everything is finished up. In the space between living and dying, Moore begs us to remember all that he is telling us.

Our children learned that mothering is caring for more than kin. Dad talked about it from the pulpit. Mother acted it out. More than fifteen teenagers and young adults shared our home with our children. Some were normal, but others had problems. One did not say a word for three months. At least two others were suicidal. One young man had come from a home where his father had refused to speak to him for more than a year. From childhood, our girls saw their mother respond to people in need, from unwed mothers to psychotic adults and the poor.

Carolyn loved to play, but as president of the MYF [Methodist Youth Fellowship], she pushed the group to deal with serious issues. She had a world vision. She traveled to Mexico with her high school Spanish class. Four years later, she spent a year studying in France. At UCD [University of California, Davis], she majored in international relations. As a member of Peoples Temple, she stood with the poor as they prepared for and stood in court. She expressed her caring both in one-to-one relationships and as a political activist.

From 1963 until 1972, when Annie left home, Annie and Becky walked with us in civil rights and anti-Vietnam War marches. We were together in supporting the farm workers’ struggle to organize. They stood in silent peace vigils. In high school they bore witness to peace with justice in our world. Their youth group provided a camping experience for foster children. When Annie was sixteen, she worked as a volunteer in Children’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. She worked directly with the children, playing with them, playing her guitar and singing. The children loved her. She decided that she wanted to work on a burn unit, which she did at San Francisco General Hospital before going to Guyana.

Our children took seriously what we believed about commitment, caring about a better, more humane and just society. They saw in Peoples Temple the same kind of caring for people and commitment to social justice that they had lived with. They have paid our dues for our commitment and involvement.

From the feeding of the five thousand, to the teenagers who stayed for months, to the psychotic adults, to the healing of the lame, John Moore reminds us of what the journey to the cross has been like. The story is not as simple as one moment in time, just as the story is not as simple as a bunch of bodies littered about in Jonestown. “The story is complex, damnit!” “Carolyn!” “Annie!” “Remember!” In that moment, I looked up to see Moore on his cross with his two daughters beside him. They shouted in unison: “Remember the farm workers we struggled with!” “Remember our fierce opposition to the war in Vietnam!” “Remember how we bore witness to peace with justice!” “Remember!” They took the cross seriously, because Moore took his cross seriously.

In fact, Moore led them to Peoples Temple. Perhaps their deaths were part of the cross that Moore showed them. While it is easy to cast blame, it is harder to look the way of Judas and bestow righteousness, realizing that he is necessary for the salvation of the world. God is in Judas as much as Judas is in God. Moore refuses to let us forget our interconnectivity, our need to follow the cross in order to bring salvation to the world. Moore reminds us to have mercy on those who cannot understand the violence of love.

The second question we have been asked is: “What went wrong?” What happened to turn the dream into a nightmare? I shall mention two things that were wrong from the beginning. These are idolatry and paranoia. I speak first of idolatry.

The adulation and worship Jim Jones’ followers gave him was idolatrous. We expressed our concern from the first. The First Commandment is the first of two texts before me. Our children and members of Peoples Temple placed in Jim Jones the trust, and gave to him the loyalty that we were created to give God alone.

It’s not that they were so different from other mortals, for idolatry has always been easy and popular. The more common forms of idolatry are to be seen when people give unto the state or church or institution their ultimate devotion. The First Commandment says “No!” and warns of disastrous consequences for disobedience. The truth is that the Source of our lives, the One in whom we trust and unto whom we commit our lives is the Unseen and Eternal One.

To believe the First Commandment, on the other hand, affirms that every ideal and principle, every leader and institution, all morals and values, all means and ends are subordinate to God. This means that they are all subject to criticism. There was no place for this criticism in Peoples Temple.

Idolatry does have consequences. Moore is well aware. Over time, Moore saw his children give their lives over to Jim Jones, thinking that they were actually giving their lives to God. Such a perversion took a huge shit on justice and almost completely buried it. Yet, Moore helps us dig down a little bit and find justice once more. Though the justice still had a stench, there was no mistaking it. The idolatry couldn’t mask the righteousness. The “disastrous consequences” were averted. Death couldn’t live forever. There was beauty to be found beneath the cross. Idolatry was dead.

The second thing that was wrong was paranoia. This was present through the years that we knew Peoples Temple. There’s a thin line separating sensitivity to realities from fantasies of persecution. Jim Jones was as sensitive to social injustice as anyone I have ever known. On the other hand, he saw conspiracies in the opposition. I remember painfully the conversation around the table the last night we were in Jonestown. Jim and other leaders were there. The air was heavy with fears of conspiracy. The entire conversation on Jim’s part dealt with the conspiracy. They fed each other’s fears. There was no voice to question the reality of those fears.

“Jim Jones was as sensitive to injustice as anyone I have ever known.” I bet nobody expected him to say that shit. This cat had just led more than nine hundred people to their deaths, and here Moore was extolling his virtues. But one has to listen. The problem is that most people can’t accept complexity. Most can’t listen. But Moore was not going to be denied. The cross is too powerful to be ignored. Moore had been to Jonestown. Moore had talked to Jones. Moore had breathed the complexity of it all. Whether he admitted it to himself or not, Moore knew what idolatry and paranoia always birthed: death. Surely, there is a lesson here. Surely, over nine hundred crosses speak beyond the jungles of Guyana. How sensitive are we to injustice?

As their fears increased, they increased their control over the members. Finally, their fears overwhelmed them.

The death of hundreds and the pain and suffering of hundreds of others is tragedy. The tragedy will be compounded if we fail to discern our relation to that tragedy. Those deaths and all that led up to them are infinitely important to us. To see Jonestown as an isolated event unrelated to our society portends greater tragedy.

Jonestown people were human beings. Except for your caring relationship with us, Jonestown would be names, “cultists,” “fanatics,” “kooks.” Our children are real to you, because you know and love us. Barbara and I could describe for you many of the dead. You would think that we were describing people whom you know, members of our church. If you can feel this, you can begin to relate to the tragedy.

If my judgment is true, that idolatry destroyed Peoples Temple, it is equally true that few movements in our time have been more expressive of Jesus’ parable of the Last Judgment of feeding the hungry, caring for the sick, giving shelter to the homeless and visiting those in prison than Peoples Temple. A friend said to me Friday, “They found people no one else ever cared about.” That’s true. They cared for the least and the last of the human family.

“There is no fear in love.” The people of Jonestown were love, not fear. Not because they were perfect, but because they were made in the image of love. And fear can never beat love.

Moore speaks from his cross once more, reminding us of the love that such a cross holds. The humanity of love. The humanity of Jonestown. The humanity of a better tomorrow. From the cross, Moore helps us to look beyond the moment and to actually see the souls gathered in front of us. There are hundreds of beautiful creations of God gathered to declare in unison, “Love wins! Love wins! Love wins!”

Then, Moore urged us to look closer. Gathered amongst the people of Jonestown were the hungry, the sick, the homeless, the imprisoned. I could hardly believe my eyes. The name of the multitude was Jesus and Jesus was the name of the multitude. “Holy shit! They did it! They actually became that which they set out to be, the very incarnation of love.” “They found people no one else ever cared about.” They found the Christ. Death was dead. Life was alive. Moore cheered from the cross.

The forces of life and death, building and destroying, were present in Peoples Temple. Death reigned when there was no one free enough, nor strong enough, nor filled with rage enough to run and throw his body against a vat of cyanide, spilling it on the ground. Are there people free enough and strong enough who will throw themselves against the vats of nuclear stockpiles for the sake of the world? Without such people, hundreds of millions of human beings will consume the nuclear cyanide, and it will be murder. Our acquiescence in our own death will make it suicide.

The forces of death are powerful in our society. The arms race, government distant from the governed, inflation, cybernation, unemployment are signs of death. Nowhere is death more visible than in the decay of our cities. There is no survival for cities apart from the creation and sustenance of communities within. Cities governed by law, but without a network of communities which support members and hold them accountable, these cities will crumble, and will bring down nations.

This is what made the Jonestown experiment so important for us. It was an effort to build this kind of common life. Its failure is our loss as we struggle against the forces of death in our cities.

I have talked of history and our personal histories, of our journeys and our choices. Providence is God’s working with and through all of these. God has dealt with tragedy before, and God is dealing with tragedy now. We are witnesses to the resurrection, for even now God is raising us from death. God whom we worship is making all things new.

Our Lord identified with the least of humans. Christ is present in the hungry and lonely, the sick and imprisoned. Christ, the love and power of God, are with us now. In Christ we are dying and are being raised to new life.

My last words are of our children. We have shared the same vision, the vision of justice rolling down like a mighty stream, and swords forged into plows. We have shared the same hope. We have shared the same commitment. Carolyn and Annie and Kimo served on a different field. We have wished that they had chosen ours, but they didn’t. And they have fallen. We will carry on in the same struggle until we fall upon our fields.

No passage of scripture speaks to me so forcefully as Paul’s words from Romans: “Nothing, absolutely nothing can separate us from the love of God we have known in Christ Jesus our Lord.” This week I have learned in a new way the meaning of these words of Paul: “…love never ends.”

Successes of common life are all of our successes. Failures of common life are all of our failures. Moore leads us constantly to death to find life. I guess Jesus did too. Tragedy cannot be disentangled from triumph. Moore got down off the cross. We were taken to a high mountain. From there, we watched as the souls of Jonestown ascended to the heavens, forming the new creation. In unison we shouted, “Nothing, absolutely nothing can separate us from the love of God we have known in Christ Jesus our Lord.” I had never believed those words more than I did in that moment. In a short personal/theological interaction, Moore spoke as clearly about love as anyone has since Jesus walked the earth.

Now may the Word which calls forth shoots from dead stumps, a people from dry bones, sons and daughters from the stones at our feet, babies from barren wombs and life from the tomb, call you forth into the new creation.

The bones of Jonestown can/will live. John Moore made sure of it.

Amen.

Amen.

(Rev. Dr. Jeff Hood is a Baptist pastor, theologian and activist living and working in Arkansas. Dr. Hood’s extensive work has appeared in numerous media outlets, including in the Dallas Morning News, Huffington Post, Fort Worth Star Telegram, Atlanta Journal Constitution, Los Angeles Times, WIRED magazine and on ABC, NBC, CBS, CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, and NPR. He writes regularly at https://www.patheos.com/blogs/jeffhood/.

(Jeff’s other article in this edition of the jonestown report is Bringing the Death Tape to Life: A Homily. His complete works for this site may be found here. He can be reached at jeffrey.k.hood@gmail.com.)