[Editor’s note: This article was originally published in Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Volume 22, Issue 2, pp. 65-92 (2018) and is republished with permission.]

ABSTRACT: Peoples Temple achieved impressive objectives as an organization, the most impressive of which was establishing and maintaining an agricultural community—the Promised Land—in the remote jungle of Guyana. An activity theory analysis of work oriented to the Promised Land reveals that texts—everyday genres such as forms and lists—were important tools used by the group to achieve this objective. A study of these textual tools helps us to understand how Peoples Temple was able to meet its collective organizational goals and how individual members achieved personal transformations within the organization. Examining the group’s textual practices adds depth to existing studies of Temple history by showcasing the efficacy of organizational labor that members themselves might have taken for granted. In addition, this methodological approach provides a view of Peoples Temple work unencumbered by the social problems paradigm, offering instead an approach that is compatible with a social possibilities paradigm.

Plain and simple, we built a city out of nowhere. —Mike Touchette[1]

For wee must Consider that wee shall be as a Citty upon a hill. The eies of all people are uppon Us, soe that if wee shall deale falsely with our god in this worke wee have undertaken, and soe cause him to withdrawe his present help from us, wee shall be made a story and a by-word through the world.

—John Winthrop[2]

Peoples Temple began in Indiana in the 1950s as a racially integrated social gospel church. This was no small feat considering the social climate at the time. Eventually Peoples Temple—an integrated group of working class whites and blacks from Indiana—migrated to Northern California, where membership grew considerably and further diversified. Upper-middle class whites dedicated to community activism found their way to Peoples Temple, as did urban youths interested in political revolution. Older blacks were drawn to the social gospel message offered by Peoples Temple, as well as to the social services the organization provided, such as assistance with healthcare and housing. The late Mary Sawyer characterizes members’ motivations for joining: “People joined Peoples Temple for one of two reasons: in order to give help, or in order to receive it. . . . In practical terms, Peoples Temple was a movement that offered sanctuary from racial discrimination, [and offered] opportunity for education and employment, and the promise of lifelong economic security.”[3]

Minutes from an 8 October 1973 meeting of the Peoples Temple board of directors describe a report delivered on “the agricultural and church extension” and the board’s decision to “establish an agricultural mission in the tropics,” and names Guyana, South America, as “the most suitable place to do so.”[4] The minutes include a formal resolution to establish the mission, and outline the financial and legal powers with which the board authorizes “James W. Jones, pastor and president of said corporation and church.”[5] The resolution would result in the community variously known as the agricultural mission, Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, freedom land, the Promised Land, and Jonestown.[6]

As noted by Rebecca Moore, the popular canon on Peoples Temple is largely restricted to a limited set of images and narratives about the group, and those images deal with the final events at the agricultural community: photographs of bodies piled on the ground in Guyana, the corrugated metal vat of poison nearby juxtaposed with images of the group’s dark-haired charismatic leader, eyes cloaked in aviator shades, hiding evil intent.[7] Moore rightfully laments the stability of the reductionist popular narrative and the difficulty that scholars confront in widening this scope to allow for a more nuanced understanding of Peoples Temple. Her concerns also invoke larger disciplinary conversations about the need to shift the paradigm that unites research on new religious movements. Sociologist David Feltmate uses the term “social problems paradigm” to describe the current orientation, which arose as researchers advanced counterclaims in response to arguments depicting new religions as cults or social threats.[8] It could be said, perhaps, that researchers of new religious movements—especially those seeking to offer robust analyses of those movements—were necessarily in a defensive posture. To elbow out room for non-dominant stories to be heard, they had to first push against existing dominant views of their objects of study. The trouble with this, Feltmate explains, is that we cannot “understand these groups and find multiple ways to dignify the human beings who engage with the worlds they create” if our starting point is rooted in the social problems paradigm.[9] Feltmate seeks a solution in a reorientation that takes “social possibilities” as its unifying concept. This new paradigm would align with the underlying existential inquiries of these groups, which address a question fundamental to human activity: “How then should we live?” New religious movements, he observes, “are experiments in addressing this question. Sometimes they are failed experiments, but that does not mean we should dismiss them. When religions are new they provide us with a wide variety of answers to the question of how people have lived and how we should live. This is not a social problem; it is an invitation to social possibility.”[10]

For a number of reasons, Peoples Temple lends itself to being examined from a social possibilities perspective. To begin with, researchers have already made a good case that the scope of Peoples Temple, both in form and function, is too capacious to be encompassed by the term cult.[11]In addition, when we look across the Temple’s history, we see two constants: a focus on social justice objectives and an organizational structure that facilitated the Temple’s internal and external work.[12] As an organization, Peoples Temple was generative, ambitious, forward-looking, engaged with society, and productive. In describing the group’s overarching objective, one former member states, “[W]e were going to convert the world to brotherhood. And that was it. That was the dream.”[13] Together, members pursued goals rooted in social justice efforts meant to address class-, race-, and sex-based inequalities and were a small part of a larger movement in the United States seeking to right the course of history.[14] They continually asked in word and deed, How then should we live? The Peoples Temple Agricultural Project was their most ambitious answer to that question. One of the most unfortunate downstream consequences of the popular narrative’s dominance is that it cuts off the instructive capacity offered by a monumental project such as Jonestown. Although it is understandable that a good deal of what has been written about Peoples Temple takes as its starting point the group’s end—much of it is threaded through the eye of the needle of 18 November 1978—this focus, whether overtly stated or implied, seems to needlessly stymie lines of inquiry that could be more productive. After all, Peoples Temple beat back the jungle to build a town in a foreign country.[15] In doing so, members reinvented themselves as a group and offered a transformative experience to individuals. Mary Maaga captures the awe inspired in some observers: “Jonestown as a physical site was a miracle of construction and dedication, a fact that is not widely appreciated when one only sees it in photographs with dead bodies strewn about.”[16] The Rev. John Moore, father of two Temple members, visited the Guyana settlement, and he described it in terms that convey the scope of the group’s achievement:

“Impressive” was the first word to come to mind when I was asked what I thought of the project. The clearing of more than eight hundred acres from the midst of the jungle, and the planting of crops is impressive. To imagine more than a thousand Americans migrating to Guyana and working in the project is impressive. Every aspect of the work and life there I found impressive.[17]

How did Peoples Temple achieve such an impressive feat? This is the question that seeded my research. When I began to investigate the building and maintenance of Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, I discovered that the “how” was a matter of member contributions (labor and money), timing, and—significantly—texts.

ANALYTICAL APPROACH

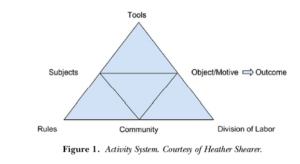

To examine complex work within organizations, researchers have made good use of activity theory, which despite its name is not a theory, but a framework developed by Aleksie Leont’ev, Alexander Luria, Yrjo Engestrom, and others from Lev S. Vygotsky’s distributed theories of psychology.[18] Activity theory takes as its object of study goal-directed human labor, and defines that labor as social (conducted with/in relation to others), historical (developed over time), and mediated by the use of artifacts (tools). Furthermore, because of its origins in Vygotsky’s work, activity theory conceives of consciousness not as “a set of discrete disembodied cognitive acts (decision making, classification, remembering),” but instead as “located in everyday practice: you are what you do. And what you do is firmly and inextricably embedded in the social matrix of which every person is an organic part.”[19] This matrix, what researchers refer to as the activity system, includes not just people pursuing an outcome, but also the tools they use as part of their work. Thus, activity theory is a systems-based approach to studying human labor that privileges human intention and views cognition as being embodied, tool-mediated, and distributed. We don’t work alone; we work with others through tool use in pursuit of achieving some end. Work is governed by rules relevant to the community or communities involved. This framework is appropriate for investigating Peoples Temple’s work from a social possibilities perspective because of its focus on goal-directed action; people are assumed to have agency and intention. Figure 1, Activity System, depicts the components of the activity system.

Key to this framework is the definition of tools as “instruments, signs, procedures, machines, methods, laws, [and] forms of work organization” that mediate the work in a given activity system.[20] Tools are not only the things we might traditionally think of (hammers, paintbrushes, bulldozers, saws), but also abstract “objects” (frameworks, customs, language, methodologies) that facilitate our work with other people. Texts are one tool used by humans in the pursuit of achieving goals, and some would even say texts are the most important tool.[21] That is, to research the work of an organization is to research the communication produced by that organization. Although participants in an organization might be unaware of the complex meaning embodied in the mundane, routine texts they produce in the course of “doing business,” there is, in fact, great value in our examining the texts not just for what they say, but also for what they do—what they permit, proscribe, or make possible. This outlook rests on the claim that to separate out “communication” from “work” is faulty; communication is a fundamental part of the organization’s work. Maryan Schall, in her oft-cited article on the social nature of organizational communication, makes this point when she explains that “like cultures, [organizations] have been considered communication phenomena, that is, entities developed and maintained only through continuous communication activity—exchanges and interpretations—among its participants. Without communication and communicating, there would be no organizing or organization.”[22] This is true for collective work (writers and readers coming together as “we”) and individual work (individuals carving out space for the “I”). The benefit of activity theory is that it requires us to account for tool use, and this allows us to arrive at new understandings of how work is accomplished. In this case, it highlights the important role that texts—paperwork of many stripes—played in building and maintaining the Promised Land.

Indeed, even a cursory examination of the Peoples Temple archives at the California Historical Society (CHS) makes it clear that Temple members made use of writing in pursuit of their organizational goals.[23] The collection of texts they left in their wake is an entity unto itself. According to the CHS, the collection of Peoples Temple records alone occupies 145 linear feet. Fielding McGehee’s description of the variety of items contained in the collection suggests its heft and richness:

[T]hey saved everything. There are the business records of Peoples Temple as a corporation, including receipts, tax records, bank accounts, and internal memoranda. There are the trappings of the Temple as a church, ranging from Jim Jones’ robes to donation envelopes, from prayer requests to testimonials of Jones’ healing powers. There are the ephemera from the community at large, such as copies of Peoples Forum, the Temple’s newspaper, membership and passport photos, handwritten requests for extraordinary purchases, and of course, more receipts. There are individual writings, such as the private journals of at least one Temple member, confidential memos to Jim Jones and other Temple leaders, papers with signed confessions to unbelievable crimes and just as many pages which are blank except for a signature at the bottom. There are flyers for political demonstrations protesting the treatment of minorities in capitalist America, and brochures heralding a new life in Jonestown. There are letters to the editor condemning the approaching police state in America, and internal surveillance reports of Temple members.[24]

The size of the collection is not as important as the types of documents contained within. Specifically, this collection is replete with examples of “homely discourse,” such as internal memoranda and the like, that are examples of “‘de facto genres,’ the types we have names for in everyday language” (e.g., memos, letters, progress reports, applications).[25] These genres function as “a typified rhetorical way of recognizing, responding to, acting meaningfully and consequentially within, and thus participating in the reproduction of, recurring situations.”[26] The important words here are “typified,” “rhetorical,” and “recurring.” By typified, we mean that genres have identifiable features that allow us to recognize them. For example, the appeals for money I receive from nonprofit groups tend to arrive in a United States business-sized envelope decorated with images of dire situations (caged, abused animals in need of my assistance; downtrodden children who are hungry). The appeal letters contained within also carry physical markers that would allow me to immediately identify the texts, without even reading them, as appeal letters from a specific kind of organization: letterhead with an organizational logo; use of short paragraphs with certain passages emphasized through the use of bold, underlining, italics, and/or uppercase letters; a detachable portion with pre-selected contribution amounts to assist me in replying; and a self-addressed, postage-paid envelope (in most cases) to make my return reply as easy and painless as possible. I know what these items are as soon as I pull them from the mailbox.

However, genres cannot be defined simply through reference to their physical features. Any given genre needs to be understood in terms of the “the action it is used to accomplish.”[27] That is, when we identify a genre, we consider the rhetorical function it serves in conjunction with its features to make that identification. All texts are rhetorical, but genres are rhetorical in a special way. Specifically, they are recognizable textual tools that help us to respond to recurring needs (as in the case of funding an organization by soliciting money through the mail). The specifics of how one makes the appeal will depend on one’s audience, purpose, and context, and this is why we see variety when we look at instances of genres (an appeal letter from a nonprofit group looks and “sounds” different from the appeal letters from my alma mater), but there are essential similarities across instances that allow us to identify them as belonging to a specific genre—in this case, the appeal letter.

Because of their rhetorical nature, genres are social “sites” where writers and readers gather to conduct work—where writers and readers “rely on shared texts and knowledge” to participate in the co-creation of meaning. For writers, this involves “assert[ing] meaning, goals, actions, affiliations, and identities within a constantly changing, contingently organized world,”[28] which is made a bit more predictable due to the relative stability that genres offer through design and discourse conventions. For readers, this means piecing together meaning from their interpretations of texts. For both writers and readers, genres provide a guide that invokes—but cannot require—social rules and reader responses. The appeal letter might suggest certain actions to me, but I am in no way bound to fulfill those actions. In addition, although the genres afford certain actions (such as mailing in a contribution), they do not preclude, necessarily, all other actions; I can, for example, choose to use the postage paid envelope to mail something other than a contribution to the group.

All of this is to say that genres are not just forms of writing: they are discursive spaces that “situate and distribute cognition, frame social identities, organize spatial and temporal relations, and coordinate meaningful, consequential actions within contexts.”[29] Writing Studies scholar Charles Bazerman sums this up nicely when he states that “[g]enres typify many things beyond textual form. They are part of the way that humans give shape to social activity.”[30] He also emphasizes that because writing “partakes of and contributes to” the contexts and cultures from which it arises, it “bears the characteristics of the cultures it participates in and the histories it carries forward.”[31] Consequently, when we examine any given instance of genre use within an activity system—that is, when we look at how writing mediates activity—we can begin to understand how we connect our “private intentions” with “the public” and singular experiences with collective, recurrent experience.[32]

In studying the kinds of texts the Temple used to achieve its objectives and in analyzing the ways that individual Temple members used these texts to navigate the Temple’s structures, we can see more clearly how the Temple was so effective at accomplishing the ambitious objectives it set for itself. This type of analysis is significant because it forces us to look at items (or characteristics of items) that we normally look past, such as layout, font, or connections to other texts. Furthermore, because genres are social sites that connect individuals with larger social structures, we can gain insight into personal agency, the possibilities and promises, available to Temple members as they participated in building and maintaining the Promised Land.

TEXTUAL TOOLS: MEDIATING COLLECTIVE AND INDIVIDUAL ACTIVITY

Almost any project involving Peoples Temple texts needs to carry a qualification similar to that provided by Rebecca Moore in Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple. She uses the word “problematic” to describe the source materials available. This has to do with the conflicting views of Temple life—those who left the Temple have a different view of it than those who remained—and the fact that survivor accounts are “written looking backward, through the prism of the deaths in Jonestown. The event altered memories and reflections so that people saw things in a different light.” More to the point is the fact that there are not nearly enough survivor accounts; all those who died were silenced, and it is impossible to reconstruct their thoughts from the materials left behind. Still, this analysis is useful because it examines items intended for routine business use or internal Temple work, which means that some of the concerns about truth and audiencemight be less central. However, we do confront the distance of time and the limits of text.[33]

To understand how the work of building and maintaining the Promised Land offered possibilities to Peoples Temple members, I provide an analysis of emigration texts used in the process of deciding who to “send over.” Although it would be possible to focus on any number of texts from the Temple’s history by way of conducting this analysis,[34] those dealing with the Promised Land are compelling because they involve a turning point in the Temple’s history.

A formal lease for 3,853 acres was signed with the Guyanese government on 25 February 1976, although work on finding an appropriate location had begun in 1973.[35] Timing was important. The contract with Guyana moved quickly because the country felt that having a United States presence on the unsecured border with Venezuela could be beneficial in preventing encroachment. The influx of United States citizens into the remote jungle territory would bring with it other benefits, including proof that the interior could be developed for the economic benefit of Guyana and its citizens.[36]

Much physical labor was needed to build and maintain the Promised Land. Even if we set aside all of the stateside work that supported the agricultural community’s development, we still find cause to be impressed. Mike Touchette, one of the settlers, recalls:

When we started . . . we went out with our surveyor. I’ll never forget it. They had a little footpath that they were following. There were so many trees. They had maybe three or four Amerindians in front of us, and there was three or four of them behind us. All of them had machetes. And what they did, as we’re walking in, they were cutting, making a trail. . . . When you walked through that jungle, you could turn 360 degrees and have no clue where you’re at. That’s what I saw. . . . At the end, we had over fifteen hundred acres in cultivation of every type of tree, plant, food, anything that we could eat was growing. . . . Plain and simple, we built a city out of nowhere.[37]

And build a city they did, one that included all of the trappings we would recognize as being necessary to a community, including those providing education, policing, housing, medical care, consumables (food, soap, clothing), and utilities (including power and communication).[38]

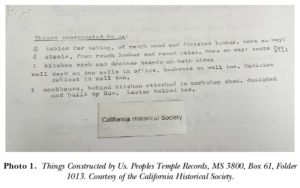

However, from the beginning of the project, textual labor was important to introducing and building the agricultural community. In fact, the quote in the title of this article—“Verbal orders don’t go—Write it!” appears on a memo pad used by Temple members during the construction of the Promised Land. Internal Temple documents were used to formalize intention, such as the resolution to establish the agricultural community. Texts also allowed the Temple to coordinate with outside entities, such as members of the Guyanese government, in securing the land and taking other legal steps to safeguard the community’s presence.[39] Progress reports written by Temple leadership and settlers communicated key information to establish future plans. Some of the early textual work provided not only a report on progress, but also an indication of the satisfaction and joy settlers felt. One of the best examples of this in the records—one of the most genuinely joyful texts in the entire collection—is the short missive from Guyana depicted in Photo 1, Things constructed by us.

The function of this passage—at once a progress report and an evocation of many good things to come—is suggestive of the potential the move to the Promised Land offered to members.

The fact that the Temple attracted members from different walks of life indicates that people were able to find what they needed at the time.[40] Odell Rhodes’ experiences reflect those who were encouraged, and perhaps for the first time invited, to find value as a productive member of an industrious group effort. Not only was he able to address his substance abuse problems through his participation in Peoples Temple,[41] he also found a new identity as a worker whose contributions were valued. Recalling his early work with the Temple as a helper in the day care center and the subsequent praise he received for this work from Jim Jones, Rhodes reflected,

I guess at that point, I couldn’t even remember the last time somebody told me I was doing good at anything, and for Jones to take the time from everything else he had to think about to notice me—well, it meant a lot to me right then.[42]

Other Temple members, people who were no stranger to past praise from teachers or supervisors, found relief from themselves. Dick Tropp, a Temple member who collected oral histories from members for a never-completed book about the history of the group, offered the following assessment of how his perspective had changed and what he gained from that change:

I have found a place to serve, to be, to grow. To learn the riddle of my own insignificance, to help build a future in the shadow of the apocalypse under which I felt I was always living. . . . I look back on the past as if to another world, a dead and dying world. A new center of gravity has been established in my life—and, to my great relief and happiness, it is not me.[43]

In speaking about their experiences, many former members offer descriptions that reveal a tension between something gained and something lost. Jean Clancy recounts her own reluctant transformation, which was prompted by aspects of the Temple that spoke to her sense of personal responsibility regarding social justice:

So why did I stay? I stayed. I got gradually re-formed or reshaped into this. Also there were some very heavy pulls. . . . Such a sense of good committed people really trying to establish an alternative way of being together— economically, socially—it really did have a strong pull. It was not an easy integration on my part, but I felt like I was supposed to be there. This is my job. This is my duty.[44]

In the end, though, she experienced this process as one of submission: “Pretty soon you are no longer thinking your own thought or being your own person: you are a penitent in this process of becoming the socialist entity.”[45] Another member, Janet Shular, describes the “dichotomies” of the “Peoples Temple experience.” On the one hand, most members “were the ‘living dead’ until they were on that final tract [sic] that led them to becoming the ‘dead dead,’” but on the other hand, “[m]ore people, just as a result of meeting and joining PT, had a true rebirth in terms of a greater zest and love for living than you could possibly imagine. I mean, they were energized to serve their fellow man at every level.”[46]

Participating in the Promised Land was an opportunity that distilled and concentrated the possibilities of the Peoples Temple experience. According to Tanya Hollis, a former archivist at the California Historical Society, “The move to Guyana might have encompassed, on the part of the rank and file, both their aspirations for self-determination and their loss of faith in the secular democratic system, with its legal assurances of their rights and systematic denial of those rights.”[47] The textual tools used by the Temple to process members’ emigration applications reflect the transformative possibilities present in Temple life and the tensions of being reshaped into the image of a productive member.

Applying to “Go Over”: Pledges and Preferences

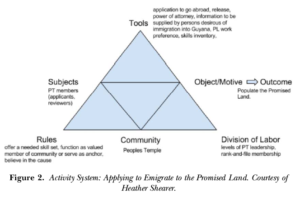

Travel to Guyana was not possible—quite literally—without texts. At the very least, travelers would need a passport, proof of immunizations, and the required immigration forms.[48] To apply for emigration to the Promised Land, members also needed to make use of documents that served Temple needs. Figure 2, Activity System: Applying to Emigrate to the Promised Land, depicts the activity system of members seeking to “go over” to the Promised Land, with a focus and emphasis on texts internal to the organization. Subjects are Peoples Temple members involved in the emigration process, either as applicants or as reviewers of applications. The community would include the larger organization. The object/motive of their goal-directed activity is to facilitate emigration to the Promised Land, and the tools used to mediate their activity include a core set of texts developed by Peoples Temple over time and in response to the group’s needs.

For members “going over” a standard set of texts was used. This set included applications for travel, forms that collected information about travelers’ health, paperwork that limited the liability of the organization in case of adverse events occurring during travel or in Guyana, forms that assigned power of attorney to Temple leadership, and forms that collected work-related background information on applicants. Taken as a whole, this set of texts required members to express their commitment to the Temple and validate its mission, offered members the opportunity to express a desire for the kind of work they hoped to contribute to agricultural community, and provided the organization with ways of surveying and managing the human capital available.

To an outsider, the amount of paperwork—and the personal nature of the paperwork—required for consideration as a Promised Land ´emigré might seem daunting. Yet, Temple members were used to information being collected about their personal lives, including financial and medical information. Such information was used to guide members through government bureaucracies involving Social Security Administration (SSA) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI), obtain health care outside of the Temple, apply for and attend college or certificate programs, and manage communal living arrangements. To a great extent, personal identity was part of the group’s collective resources. People’s lives were managed by the group, including aspects typically assigned to nuclear family structures, such as the care of children. These arrangements of members’ personal lives were bound up with the organization’s textual practices. For instance, the legal responsibility for Temple children was signed over by parents to other Temple members through guardianship paperwork.

Figure 2. Activity System: Applying to Emigrate to the Promised Land. Courtesy of Heather Shearer.

As we consider the textual work used in conjunction with emigration to the Promised Land, it is worth remembering that when the project was proposed, a mass migration was not intended. Because it was, at least initially, believed to be something to which not all had access or equal access—yet something that for many was desirable—it is interesting to consider the ways that members used the means of persuasion available to them in completing the application paperwork. Additionally, because the Promised Land was viewed as the apotheosis of Peoples Temple work (the name is telling), the texts used for emigration purposes are interesting in what they reveal about Temple values and what they might disclose about the aspirations of individual members.

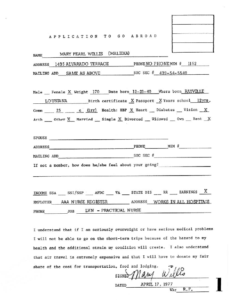

The document titled “Application To Go Abroad” is a useful place to start (see Photo 2, Application To Go Abroad).[49] Based on the layout of the document and the nature of the information collected, we see that this one-page document clearly belongs to the genre of “application,” and, like most instances of that genre, serves the needs of the applicant and those reviewing the application. For the applicant, it was a way to begin the emigration by signaling interest to those who shared power for authorizing that travel. The form also offered opportunity for persuasion. For example, there was opportunity to signal greater integration in or commitment to the group in the section of the form that solicited information about the applicant’s spouse. Not only was spousal information requested, but if the spouse was not a member, a characterization of his or her attitude toward the member’s emigration was also solicited: “If not a member, how does he/she feel about your going?”

For reviewers, especially before the mid-1977 rush to send as many members as quickly as possible to Guyana, the information collected through the application allowed the organization to prioritize based on applicants’ integration in the organization, financial means, health profile, and existing ability to travel. For instance, the form allows applicants to indicate if they have a passport or birth certificate (the former would be needed for travel and the latter to secure a passport). Spousal information could certainly be useful in avoiding (or perhaps heading off) unnecessary conflict. Questions about finances could assist the Temple in identifying those with a desire to go who could provide financial support to the project. The issue of finances is directly invoked in the bottom portion of the form, which contains a warning about health concerns and the cost of emigration:

I understand that if I am seriously overweight or have serious medical problems I will not be able to go on the short-term trips because of the hazard to my health and the additional strain my condition will create. I also understand that air travel is extremely expensive and that I will have to donate my fair share of the cost for transportation, food and lodging.

Photo 2. Application To Go Abroad. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown&Peoples Temple. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/04-05-GoabroadApp. pdf[CW1] .

As with many Temple forms, a signature of the member was required, which created a potential textual link to a network of legal practices. This form allowed members to signal interest, to maneuver for consideration, and to indicate commitment to Temple rules (including the handing over of personal information). In addition, the form, taken in consideration with a host of other texts, sanctioned the Temple to facilitate the emigration process.

Still more interesting is a small cluster of documents represented by the following texts: “Information to be supplied by persons desirous of immigration into Guyana”; “Questionnaire”; “Skills Inventory”; and “Promised Land Work Preference.”[50] The first of these (“Information to be supplied . . . ”) appears to have a direct external audience: the Guyanese government. The form’s title includes the phrasing “desirous of immigration,” which sounds odd to those who speak American English. And some of the questions are strange, if indeed the form was created by the Temple and intended mainly for internal use. For example, the form asks for “country of origin” of applicants, but Temple members were from the United States. Moreover, it includes a request for the applicant to “submit . . . a certificate from the police authority of the country (or countries) where he (she) has been resident during the last ten (10) years, to the effect that there has been no conviction against him (her).” At the same time, the form does include questions that seemed to target Temple members specifically, such as its question asking applicants to “[s]tate whether [they] are prepared to work and live in the interior of Guyana,” details of applicants’ farming experience, and information about “assets (including cash).” With reference to the latter, one standard response, generally typewritten—which means that it could have been prepared ahead of time for those completing the form—is this phrase: “All assets are to be imputed to the Peoples Temple Agriculture Project which has leased land from the government of Guyana under the F. C. H. Program.”[51] Each of these items directly speaks to the Temple’s work at the agricultural community in Guyana’s interior and to the Temple’s ongoing financial needs.

By comparison, the document titled “Questionnaire”[52] seems to be intended wholly for an internal audience. The two-page document contains forty-four questions and, like many Temple forms, solicits detailed information about the general demographic, health, and financial status, including monies contributed to Peoples Temple. It also asks questions specific to the management of the individual’s international travel as a member of the group (e.g., “Do you have a passport? Have you turned it in to Grace?”), and underscores the need for accurate information that could be used to secure travel documents if need be: “What is your full name? Your date of birth? Your place of birth?”[53]

In addition, the form provides opportunities for applicants to express interest in the agricultural project and position themselves as a desirable candidate. Item forty-two directs applicants to

[l]ook at the attacheet [sic] of Skills and tell me which of the things listed you can do, how many years experience you have at each, or how many years of college you have in each. Be detailed. List out to the right in the blank space, for example, the vegetables you know how to cultivate, etc.

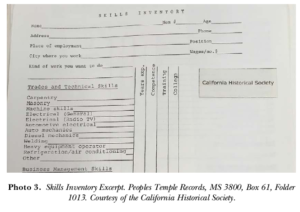

I could find no item in the records titled “list of skills,” but there is a document called “Skills Inventory,” which is designed in a two-column table format with headings and subheadings. Two versions of this inventory appear in the CHS collection. The skills listed are identical, but one version contains a header on the top of the first page that solicits information about the member (name, member number, age, address, phone number, employment and current position, location of job, and wages per month). This version also includes a small space for the member to indicate the “[k]ind of work you want to do.”

Photo 3, Skills Inventory Excerpt, presents a portion of the first page of this form. Both versions provide opportunities for the applicant to position himself or herself as a desirable candidate for emigration to the Promised Land. After all, certain skills, especially early on, were highly valued and more in demand. In addition, the version of the form with the header invites applicants to express a desire in terms of the labor role to which theymight be assigned. The space provided to describe the “kind of work you want to do” is comically small. Nevertheless, its inclusion is significant. The Promised Land was the next stage in the organization’s history, and it offered a fresh start for those who moved there. The work in the Promised Land would differ in scope if not always in kind from the work at Temple sites in California. Being asked what one wanted to do was a call to reinvent oneself—a call that most Temple members in the United States recognized, even if they did not seek it themselves.

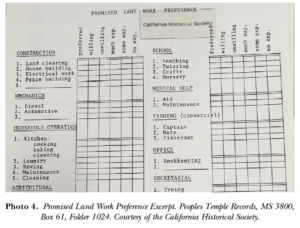

The “Promised Land Work Preference” (PLWP) form is more obvious in its promise of possibility. To begin with, the title seems to offer personal agency. Not only does it name the site of the labor (Promised Land), it also explicitly indicates that preferences will be taken into consideration. Moreover, unlike the “Skills Inventory,” this form asks applicants to describe not only what they have done, but also what they hope to do. More than two pages long, the form provides applicants with a list of items related to tasks that would contribute to the building and maintenance of Jonestown, and it solicits their interest in conducting labor associated with each item (preferred, willing, unwilling), as well as their experience with tasks associated with each item (much exp., some exp., no exp.). Photo 4, Promised Land Work Preference Excerpt depicts the first page of the PLWP. Of the forms available to Peoples Temple members—and here I mean all forms available to members, not just those related to emigration to the Promised Land—this one stands out for its relative flexibility and the diversity of responses it elicited.

In reviewing completed forms in the records, one can see members negotiate the social space opened up by the PLWP in different ways. It is clear that some members had assistance when completing the form. This is evident in the notes written on some of the forms that refer to the applicants in the third person. For instance, one hand-written annotation reads, “She wants to work with children.” Some applicants express a preference to conduct work with which they already have experience. One member with a background in construction, for example, expressed a desire to do “fence building” and “painting.” Others attempted to carve out a different identity for themselves or, perhaps, better position themselves as the kind of worker needed in the Promised Land. Two examples illustrate this: the applicant with experience as a nurse’s aide who expressed a desire to do electrical work and ended up doing that; and the applicant with experience as a teacher’s aide and office work who indicated that she wanted “to build.”

The ways of completing the PLWP form are also suggestive. Some people checked each and every box containing relevant information, sometimes stopping to cross out an initial checkmark and offer a revised response. This shows care and intention in completing the form, though we cannot know what that intention was. Other applicants marked only those things with which they had experience and indicated their willingness— or not—to continue with that work, leaving the rest of the items blank. Of course, there are members who, once in the Promised Land, ended up doing what they did not want to do (and this does not include agricultural work, at which everyone took a turn).[54] Here, I think mainly of the members with office experience who indicated a desire to do something other than “secretarial” work and who ended up, according to Temple records, in a letter-writing capacity.

The purpose of this analysis is not to suggest that there is a direct correlation between what people desired and what they ended up doing. However, the analysis does demonstrate that the organization designed an instance of a genre that afforded members the opportunity to express an individual desire and that members availed themselves of that opportunity. There is reason to believe that people could have viewed the invitation to express preferences as genuine. Although the Promised Land offered a distinct opportunity for transformation, the chance to change one’s sense of self through learning was part of the Temple culture. Eugene Smith, reflecting on his time in Peoples Temple, describes the mentorship he received from others. Through this mentorship, he learned about music, printing, and photography. He characterizes the easy way that practical knowledge was shared, sometimes with a dose of humor:

People were free with their knowledge. If you wanted to go into mechanics and get greasy, go down to the garage. The mechanics were an off bunch. They would make their coffee and they’d stir it with a wrench. That was their thing, “C’mon in, get some of this good coffee.”[55]

The data gathered though this application effort was massive. We see the community attempt to wrangle information like this in other texts, including a lengthy handwritten summary of the kind of information collected in the PLWP and the “Skills Inventory.” This summary, used onsite in Guyana, organizes people by their assigned work role in the community, indicated by a code. Resident names are listed, and many are accompanied by a brief write-up of skills and work experience.[56] One member’s entry reads: “Agriculture (banana grower), Lumberjack, Cement finishing, Carpentry, Industrial Painter, Hunter, Intensive farming, Hay Bailer [sic], Peanut Thrasher, high school graduate, age 53.” Many of these experiences could have been completed while in Guyana, though given the age of the member, it is likely that he brought previous experience with him. Another entry, this one for a 38-year-old resident, contains information that clearly includes experience from outside of the agricultural community: “food dietician 5 yrs, shoe factory, pillow & chair factory. Beauty shop, shampooing, dressing hair, worked bar serving food & drink, went to school for [unreadable], cashier, convalescent sanatorium maid, laundry, high school graduate.”[57]

In tracing the data through people’s stories and through Temple records, we do know that transformations in work identity occurred. It makes sense that organizing people’s labor roles would occupy so much of the Temple’s efforts. As Rebecca Moore aptly points out, it would take a lot of skilled labor to support the needs of the community. In addition, she observes that relocating to the Promised Land offered the opportunity for members to adjust their job status, either by taking on a role that would typically be viewed as a promotion, such as being assigned to a managerial role without past experience or to a role that might be viewed as a “step down the career ladder.”[58] As noted above, some people’s status remained the same, despite what seems to be (in some cases) efforts to shift roles. Linking one’s identity with one’s work role in the Promised Land was part of the tactics Jones used as part of the emigration process, broadly defined. Odell Rhodes recalls the gist of Jones’ “pitch”:

[H]e kept saying that over there a person wasn’t judged by the color of his skin or the way he talked, or who his parents were. Over there, you could be anything you wanted to be, do any type of work you wanted, make yourself the kind of person you always wanted to be—anything, just so long as you were working to help your brothers and sisters, that was all anyone was judged on over there.[59]

If the Promised Land offered a place to reinvent oneself in a community that valued, above all, one’s contributions to the cause, the textual tools with which members engaged offered one means through which they could attempt to enact that reinvention.

The network of texts relevant to emigration also included those that functioned as consent documents; the only self-determination these provide to members is in the decision to sign them or not. One example of this is the form for “Release of Medical Records and X-Rays and Lab Work,” which gave permission for the relevant medical paperwork to be sent to Dr. Larry Schacht.[60] But the consent genres often contained elements of assent, too, and these aspects were unique to the specific purposes of the Temple. For instance, embedded in a release form that absolved the Temple of responsibility for “any and all liability, claims, causes and causes of action arising out of and relating to” travel to and from sites in the United States and foreign countries, we find a passage that acknowledged that the applicant has consented to the trip and has assented—that is, “promised”—to “work diligently and in full cooperation with all leadership appointed by [Jim Jones] and to keep a cheerful and constructive attitude at all times.”[61] Several versions of the release document exist in the records, suggesting its development over time in response to the organization’s needs.

At times, instances of consent/assent genres demonstrate quite forcefully Jones’ preoccupation with control. One short form, about a half page in length, is simply titled “Statement.” It contains a statement of willingness to travel and of belief in the “aims and reasons for this mission,” a commitment to “work diligently and to be an integral part of this missionary program,” and a “pledge without reservation” of “eternal loyalty to Pastor Jim Jones and to the Peoples Temple.” It ends with positive words about Jones’ character and thanks “for all he has done for me.” The bottom of the form contains lines for the member’s signature and date of signing. There is no legal aspect to this text—this is simply a statement of rededication to the cause and to Jones. Yet, it is presented with the formality of a legal text; for instance, this could have been done verbally—as a more traditional pledge—instead of being offered as a document requiring a signature. In keeping with the Temple’s tradition of using written texts as a way to make personal information part of the organizational record, some members were asked to sign the statement. This form is not as common as are other forms, and so one has to wonder whether it was used early on (one of the completed samples was dated 12 June 1974) and then found to be redundant or unnecessary as the community progressed. The release form (described above) appears with much more frequency in the records and covers in spirit some of the same ideas regarding commitment to the Temple.

Packing and Travel (or, What We Need is a List!)

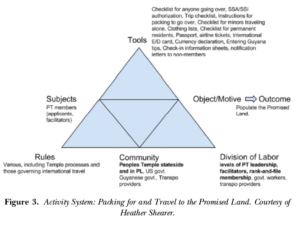

Group travel triggered a whole host of texts, many of them taking the form of a list. The level of organization required to move people to Guyana, especially beginning in late summer of 1977 when the pace picked up substantially, relied on textual practices. The stakes were higher here, as some of the textual labor had audiences outside of the Temple, and failure to succeed in meeting the audience’s needs would affect Temple operations—either in preventing the movement of members or in preventing much-needed financial support, such as that provided by SSA checks, from reaching members in Guyana.

Figure 3: Activity System: Packing for and Travel to the Promised Land depicts some of the textual tools in this activity system. In terms of getting a sense of what the process of emigrating might be like, the lists created to facilitate and ease travel are the most interesting. These were prepared for various audiences and served a number of needs. There were packing lists that told ´emigr´es what to bring and what not to bring (NO GUM OR CANDY, one intones in the top left margin). There were master lists that referred to emigration paperwork (a notecard sized “Trip Checklist” served this role) and to other lists (item #3 on the “Checklist for Anyone Going Over” is “Revised clothes list,” a list that was adjusted several times as the organization learned to better manage resources). The list titled “Instructions for Packing to Go Over” provides a catalog of rules that guided members’ packing processes. Item #2 on this inventory explains that members can take more personal items with them than can fit into their three pieces of luggage, but that these items “will have to go by surface and will not reach you for at least two months.” Another item on this list cautions travelers against transporting caffeinebased drugs considered to be over-the-counter stateside but prescription “in the P.L.” This item in particular suggests a shift in culture; what might have been normal in the United States (taking caffeine in pill form) would be viewed differently in the Promised Land. Sometimes the lists contain delightful moments, such as this item on the “Checklist of Additional Preparations,” which takes as its audience one of the people who will facilitate a group departure: “See that youngsters are washed and dressed.”[62]

The care taken to ease the process by legitimizing travelers, who, due to various factors might experience discrimination or unease when traveling, is also noteworthy. Internal Temple memos suggest that travelers’ nerves did need to be calmed. Letters of introduction were prepared for travelers. One sample letter in the records was addressed to Pan Am staff—Pan Am being the airline used by the Temple for emigration. Sample letters prepared for the airlines introduce the traveler (“Please permit me to introduce . . . ”), emphasize the nature of the organization and the reason for travel the business provided to Pan Am by Peoples Temple (“our members fly Pan Am and we ship air freight by Pan Am regularly”), and include a request to provide the “fullest cooperation” with the traveler.[63] Letters to Guyanese officials served a similar purpose. These letters were typewritten on Peoples Temple letterhead and were signed by “Michael J. Prokes, Associate Minister.” Using textual tools such as these formal letters of introduction, the Temple extended its organizational stature to individual travelers who on their own might not have carried that stature. Travelers were given directions that undoubtedly were designed to raise their public credibility. Among the instructions provided in “Instructions for Packing to Go Over,” men were advised to “have their hair cut or worked into French braids before going over.”[64]

External audiences were attended to in additional ways. Members sent personal letters to non-member acquaintances or family members ahead of travel. These were handwritten. Although they vary in content, the personal letters contain a statement about upcoming travel to the agricultural mission. The following excerpt was taken from one of the letters and is representative of the kind of language used:

[W]e are going with our pastor and some of the members to South America, [sic] we have an agriculture mission there, some of the members have been there for several months. I will write you a letter from there giving you my address, as I expect to be gone for several months. We are both well and hope you are the same.[65]

Another member wrote,

I am going to take a trip with our church and I will be gone for several months. I am going to our mission field. I will write to you when I get there and I will send you the address so you can write me. I never dreamed of having a chance like this at my old age (Ha Ha).[66]

Because of the similarity across samples, it is clear that although seeming to be a “personal” letter, these were, in fact, dual-natured and served personal and organizational ends. They were undoubtedly copied from templates developed as boiler-plate messages.

CONCLUSION

As we examine the available documentation concerning Peoples Temple, we can perceive a sense of optimism in the pages of the texts the group composed. In some cases, the optimism is obvious; in other cases, we can infer optimism and hope in the group’s industriousness, reflected on the pages of the everyday texts they composed—activity aimed at creating a new world and transformed selves that in its own way marks the group as very decidedly American. John R. Hall notes that Peoples Temple marked the end of “any interest in utopian reconstruction in American society,” despite the fact that the problems utopian communities aimed to remedy are still with us today.[67] Yet, between the time that Hall offered those words and the present, society seems to have witnessed events that make utopian reconstruction more desirable, perhaps even necessary. We are barreling toward an uncertain future under the specter of vast environmental destruction, a resurgence of white supremacy in the United States, and a return of fears about nuclear war. Members of Peoples Temple confronted similar issues, albeit in a different technological context. Many people find themselves asking, How then should we live? Just as failures can instruct, so can successes, and there are practical lessons to be learned from examining the labor of the group that created Peoples Temple Agricultural Project. One principle we can infer from Peoples Temple’s efforts is that building a successful organization requires its members to harness the social and rhetorical power offered by genres. Mundane genres matter because they mediate goal-directed activity within systems. Moreover, textual tools afford certain actions and hinder others. Understanding this can make organizations more effective and can give individual members agency within those organizations.

When we look closely at the coordination afforded by “homely” genres, we begin to understand why activity theorists put textual tools on an equal footing with things we traditionally think of as tools, such as hammers and saws. In addition, we see how activity theory might be valuable for examining the work that takes place in new religious movements because it asks us to examine the means through which people achieve objectives. Moreover, such an analysis highlights the means, such as the use of routine genres, that researchers and participants in organizations might typically take for granted. In the case of Peoples Temple in particular, we can begin to understand the fundamental role that textual tools played in mediating its efforts to send members over to the Promised Land. In addition, activity theory offers one framework for enacting Feltmate’s call to produce research from a social possibilities perspective. While activity theory is not ideologically motivated by “social possibilities” per se, its focus on goal-directed, tool-mediated activity within systems—as it occurs from the subjects’ viewpoints—nevertheless allows us to understand the social possibilities of organizations and aspirations of individuals within those organizations.

I would like to thank the reviewers and editors for their timely, insightful, and helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. In addition, I extend thanks to the research librarians at the California Historical Society for generously sharing their knowledge of the Peoples Temple collection. This research was funded through generous support provided by Montana Tech of the University of Montana and the University of California, Santa Cruz.

ENDNOTES

[1] Leigh Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 197.

[2] John Winthrop, “A Modell of Christian Charity” (1630), Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, at https://history.hanover.edu/texts/ winthmod.html.

[3] Mary Sawyer, “The Church in Peoples Temple,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004), 167.

[4] 8 October 1973, Minutes of the Board of Directors, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[5] Readers can view a copy of the minutes with the Resolution, as well as many other primary sources at Alternative Considerations of Peoples Temple and Jonestown, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/, last modified 2 July 2018.

[6] The diversity of names used to refer to the community in Guyana reflects the multiple identity of Peoples Temple, both secular and religious.

[7] Rebecca Moore, “Is the Canon on Jonestown Closed?,” Nova Religio 4, no. 1 (2000): 7–27.

[8] David Feltmate, “Rethinking New Religious Movements Beyond a Social Problems Paradigm,” Nova Religio 20, no. 2 (2016): 84.

[9] Feltmate, “Rethinking New Religious Movements,” 91.

[10] Feltmate, “Rethinking New Religious Movements,” 95.

[11] See, for example: Rebecca Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2009), 1–8 and John R. Hall, Gone from The Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History, 2nd edition (New Brunswick: Transaction, 2004). Many other scholars have discussed this issue, and other questions related to the problematic nature of popular conceptions about Jonestown—far too many to list here.

[12] This organizational structure changed over time. Most notable is the dissolution of the Planning Commission. The work of this group was taken over by administrative structures new to the agricultural project. See “Planning Commission Reorganized,” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35917, last modified 23 May 2014.

[13] Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown, 267.

[14] This is addressed in separate scholarly works by Mary McCormick Maaga, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown: Putting a Human Face on an American Tragedy (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1998), 6; Rebecca Moore and John Hall, previously cited, but also through accounts of the Temple provided by former members, including those who, looking back, are highly critical of the group. For one example, see Janet Shular’s contributions to Leigh Fondakowski’s Stories from Jonestown.

[15] Subduing the jungle landscape alone was challenging. Hyacinth Thrash, a former member who completed an oral history of her time with Peoples Temple, described the perseverance of the jungle plant life: “Grass and weeds grew so fast, you’d cut them down and two or three days later they’d be tall as you again.” Catherine Thrash and Marian Kleinsasser Towne, The Onliest One Alive: Surviving Jonestown, Guyana (Indianapolis: M. K. Towne, 1995), 86.

[16] Maaga, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown, 6.

[17] Rebecca Moore, The Jonestown Letters: Correspondence of the Moore Family 1970–1985 (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1986), 240.

[18] Aleksei Leont’ev, Activity, Consciousness, and Personality, trans. Marie J. Hall (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1978); Alexander Luria, Cognitive Development: Its Cultural and Social Foundations (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976); Yrjo Engestro¨m, “Learning by Expanding: An Activity- Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research,” The Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition, at http://lchc.ucsd.edu/mca/Paper/ Engestrom/Learning-by-Expanding.pdf, accessed 8 September 2017; Lev S. Vygotsky, Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978).

[19] Bonnie Nardi, “Activity Theory and Human-Computer Interaction,” in Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and Human-Computer Interaction, ed. Bonnie Nardi (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 4.

[20] Kari Kuutti, “Activity Theory as a Potential Framework for Human-Computer Interaction Research,” in Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and Human- Computer Interaction, ed. Bonnie Nardi (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 26.

[21] David Russell, “Rethinking Genre in School and Society: An Activity Theory Analysis,” Written Communication14, no. 4 (October 1997): 508–9.

[22] Maryan Schall, “A Communication-Rules Approach to Organizational Culture,” Administrative Science Quarterly28, no. 4 (December 1983): 560.

[23] Readers can find selections from the CHS Peoples Temple collection in Dear People: Remembering Jonestown, ed. Denice Stephenson (San Francisco: California Historical Society Press and Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2005). Additional primary source materials are available online at Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13052, last modified 25 February 2018.

[24] Fielding M. McGehee III, “Attempting to Document the Peoples Temple Story: The Existence and Disappearance of Government Records,” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/? page_id=16577, last modified 21 March 2014.

[25] Carolyn R. Miller, “Genre as Social Action,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 70, no. 2 (1984): 155. The term “homely discourse” is a pointed way of acknowledging the disdain with which some scholars regarded non-literary or non-scholarly forms of writing.

[26] Anis S. Bawarshi and Mary Jo Reiff, Genre: An Introduction to History, Theory, Research, and Pedagogy (West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2010), 212.

[27] Miller, “Genre as Social Action,” 154.

[28] Charles Bazerman, “What Do Sociocultural Studies of Writing Tell us about Learning to Write?” in Handbook of Writing Research, 2nd edition, ed. Charles MacArthur, Steve Graham and Jill Fitzgerald (New York: Guilford, 2016), 18.

[29] Bawarshi and Reiff, Genre, 95.

[30] Charles Bazerman, “Speech Acts, Genres, and Activity Systems,” in What Writing Does and How It Does It, ed. Charles Bazerman and Paul Prior (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004), 317.

[31] Bazerman, “What Do Sociocultural Studies of Writing Tell Us,” 11.

[32] Miller, “Genre as Social Action,” 163.

[33] Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 45.

[34] In fact, a comprehensive analysis of the textual work of the Temple is called for. The sheer power of the group harnessed through its textual work is relevant to the group’s general history, and such an analysis would also be instructive about activist organizational practices in the 1960s and 1970s.

[35] Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 42–44.

[36] Hall, Gone from The Promised Land, 192.

[37] Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown, 197.

[38] Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 46.

[39] See, for example, the Government of Guyana Documents available for viewing at Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, http:// jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13225. These sample documents only scratch the surface. The records contain additional texts, many of them letters written to various government officials and community members, used to establish the agricultural community and ensure its ability to operate.

[40] For a good discussion of Peoples Temple membership, see Chapter 1 of Maaga, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown, 1–13. For an analysis of the demographics of those at the Guyana site, see Rebecca Moore, “An Update on the Demographics of Jonestown,” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=70495, last modified 21 June 2018.

[41] John Nordheimer, “I Never Once Thought He Was Crazy,” New York Times, 27 November 1978, http://www.nytimes.com/1978/11/27/archives/i-never-oncethought- he-was-crazy-claims-of-superiority-unlimited.html.

[42] Ethan Feinsod, Awake in a Nightmare: Jonestown, the Only Eyewitness (New York: W.W. Norton, 1981), 92.

[43] Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown, 176.

[44] Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown, 160.

[45] Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown, 161

[46] Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown, 182–3.

[47] Tanya Hollis, “Peoples Temple and Housing Politics in San Francisco,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004), 98. Hollis also discusses the politics of living space. In the same passage, she notes that the move to Guyana could also “be seen in terms of the Temple hierarchy’s stake in the move as an extension of such an authoritarian politics of living space.”

[48] In truth, there were many texts that mediated “going over,” including airline tickets, paper currency, shipping invoices for members’ belongings, and so on. This is the nature of text in our time; one text leads to another text and to another. And of course, there were also many non-discursive tools that were integral to the group’s work.

[49] Application to Go Abroad, 18 April 1977, Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/ uploads/2013/10/04-05-GoabroadApp.pdf. A blank application can be found in Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[50] Information to be Supplied by Persons Desirous of Immigration into Guyana, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[51] Information to be Supplied by Persons Desirous of Immigration into Guyana, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society. The abbreviation “F. C. H.” refers to Prime Minister Forbes Burnham’s “feed, clothe, and house the nation” plan. For a description of this plan, see Marvin X, “A Conversation with Forbes Burnham,” The Black Scholar 4, no. 5 (February 1973): 27.

[52] Questionnaire, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[53] Included in the records are a number of requests for birth certificates for older residents. At times, the requests initiated a lengthy paper chase complicated by members’ ages (some born in the late 1800s or early 1900s), social class, and race. A number of sociological reasons account for this lack of documentation, including home births. See also the explanation provided in Peoples Temple Emigration Documents, at http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_ id=13104, last modified 15 September 2014.

[54] Feinsod, Awake in a Nightmare, 114.

[55] Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown, 238.

[56] Code II, for example, includes “Foods and Central Supply.” For a list of roles organized by code and supervisor, see “Personnel Codes,” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, http://jonestown.sdsu .edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/4b-ACAORomanNum.pdf, accessed 28 September 2017.

[57] Don Beck, Organization of Jonestown: Departments, Jobs & Activities, Residences, Courtesy of California Historical Society.

[58] Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 46.

[59] Feinsod, Awake in a Nightmare, 114.

[60] Release of Medical Records and X-Rays and Lab Work, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[61] Release, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[62] Checklist of Additional Preparations, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[63] Letter of Introduction to Pan Am, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[64] Instructions for Packing to Go Over, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[65] Adeleine and Madeleine to Hazel and Clarence, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[66] My Dear Thelma, Peoples Temple Records, MS 3800, California Historical Society.

[67] Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown, 183–84.