(Edward Cromarty is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. His complete collection of articles is here. He can be reached at edwardcromarty@hotmail.com.)

As even the most casual student of a modern historical event will quickly come to learn, there are two styles of writing that define it: the memories and insights of those who lived through the experience, and the analyses and interpretations of academics who draw upon the former for their deeper and more contextual meanings. The writings of survivors are often less formal and polished, but undeniably more heartfelt, even visceral. In contrast, the scholarly approach to the subject tends to be more professional, but also dispassionate and seemingly aloof. This academization sometimes goes so far as to make itself incongruous from the narratives of the lived event.

So it is with Jonestown.

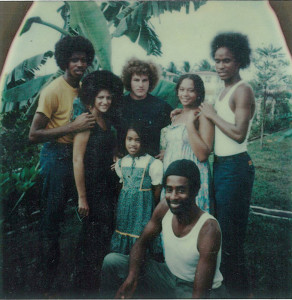

One academic effort that tries to bridge the gap is the article “Jim Jones and Black Worship Traditions,” by Milmon Harrison, published in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America (2004), which explores the spiritual foundations of Peoples Temple in the traditional Black style of worship. While the original members of the church were working class Whites from Indiana, it grew to an overwhelmingly Black congregation – 90% in California, and 70% in Jonestown – with large majorities of women and urban residents. Jim Jones himself was from a working-class background and was influenced in youth by Pentecostalism which was a working-class multicultural movement.

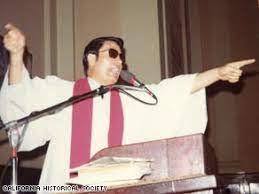

Peoples Temple found its origins in Black Pentecostal worship, which included a strong focus on social justice issues and community activism. Worship services involved active communal participation through music, singing, free expression, and body movement such as dance and clapping. Jones created an emotional experience, rather than an intellectual reading of scriptures. Rather than just preaching on the cruelty and injustice of a capitalist system, Jones backed up his words with church-sponsored social programs to improve the lives of Temple members and local community. This provided practical aspects that supported the social activism of Jones’ sermons and made Peoples Temple culturally relevant through to the lives of Temple members (Harrison, 2004).

Peoples Temple found its origins in Black Pentecostal worship, which included a strong focus on social justice issues and community activism. Worship services involved active communal participation through music, singing, free expression, and body movement such as dance and clapping. Jones created an emotional experience, rather than an intellectual reading of scriptures. Rather than just preaching on the cruelty and injustice of a capitalist system, Jones backed up his words with church-sponsored social programs to improve the lives of Temple members and local community. This provided practical aspects that supported the social activism of Jones’ sermons and made Peoples Temple culturally relevant through to the lives of Temple members (Harrison, 2004).

But what informed Harrison’s insights? Let us begin with the words of Jim Jones himself, recorded on May 3, 1978, as he spoke from Jonestown’s radio room six months before the mass deaths (Q 385). In a wide-ranging talk, Jones speaks of the social and political issues of Guyana, the USA, and the global socialist cause. He mentions the free health care and education offered in Jonestown and the need to clothe and feed the population. He describes the need for Jonestown residents of being scientific Marxist-Leninists to self-provide through mental and physical labor, and to achieve the collective consciousness and goals of the group process in coming to the knowledge of communism to participate in a new socialist society. Jones also quotes articles from One World, a journal of the World Council of Churches, which praised Peoples Temple in two recent editions as a socialistic church living the communal principles of early Christianity and of being one of the most socially active ministries in America.

But the tape includes contradictions, as Jones himself academicizes the Temple’s own lived life. He talks extensively of political and social issues through academic terms and seems to have lost touch with the working-class realities of the people of Jonestown. The experience Jones was creating had lost its cultural relevance to the lives of the people; he was no longer talking with but jargoning at the people of Jonestown.

We can see the direct connection between some of Jones’ rhetoric and the analysis of the Temple in Harrison (2004). But how do those views of the Temple reflect the experiences of the survivors? To gain some insights into this question, I chose to review some of the poetry and essays of four Jonestown survivors – Laura Johnston Kohl, Dawn Gardfrey, Jordan Vilchez, and Teri Buford O’Shea – who, among them, provide a diverse representation of viewpoints of the Jonestown population.

I begin with Survivors’ Rights by Teri Buford O’Shea. In this lovely poem Teri expresses her rights to her life experience, to disclose and extricate herself from situations that become painful. She has the right to live without guilt and to self-disclosure at her own pace. She has the right to be loved and to fall in love. She has the right to her opinions, to interpret the past, and the freedom to determine her own future. This wonderful poem expresses the human rights that all people deserve, heightened by Teri’s sensitivities to the experience of guilt, grief, and her search for meaning following Jonestown. It closes with the following lines.

I begin with Survivors’ Rights by Teri Buford O’Shea. In this lovely poem Teri expresses her rights to her life experience, to disclose and extricate herself from situations that become painful. She has the right to live without guilt and to self-disclosure at her own pace. She has the right to be loved and to fall in love. She has the right to her opinions, to interpret the past, and the freedom to determine her own future. This wonderful poem expresses the human rights that all people deserve, heightened by Teri’s sensitivities to the experience of guilt, grief, and her search for meaning following Jonestown. It closes with the following lines.

I have the right to be loved and to love again

Love for my fallen friends does not diminish my love for others now

I have a right to my own interpretation of the past

I have free will

Two Poems – No Chance for Tomorrow and Didn’t Mean by Dawn Gardfrey illustrate the simplicity and memories of children living in the rainforests of Jonestown, and the memories of love for family and friends who exist in the images of the mind but can never be seen again. She remembers experiences with loved ones and describes the sorrow and guilt of leaving without having said “I Love You,” one last time.

Didn’t realize the value of hugs

That kisses are priceless

Didn’t know

Didn’t know

That our little world in the rainforest

Would someday be gone

Three essays by Jordan Vilchez clearly depict her experiences and emotions in Peoples Temple and Jonestown. In the first essay Caught Up in Living a Lie, Jordan points out the contradictions of Peoples Temple, claiming, for example, to be an inclusive socialist organization yet staying separate from the community, espousing equality but having a mostly white leadership; and opposing human rights abuses while permitting the abuse and manipulation of Temple members. In Remembering Liane, Jordan remembers her friendship and shared life experiences with Liane Harris, who died in Georgetown on November 18. “I am grateful to have had her as a friend,” she concludes. In her earliest essay, Insight and Compassion: Vestiges of Peoples Temple, Jordan acutely describes the activities and events she experienced, and the sacrifices she made in it, such as being limited by a lack of skills usually learned in the teen and young adult years. However, she continues to describe the compassion and human insight gained. The human skills are among the most complex and important skills we can develop. As she mentions, it was a gift to have the opportunity to develop the human skills, compassion, and ability to view the world through diverse perspectives.

In Coming Out of the Peoples Temple Closet and in Seeing the Faces, Laura Johnson Kohl paints a picture of her life in Jonestown and the personal and social traumas of trying to survive in the years that followed. But it is her poem Sisterhood that is the most personal, in which she speaks of the trust and mutual protection that comes with love, the caring and responding when asked and remaining available at all times, the ability to open up and love, even when there is no mention of blood ties. The poem concludes:

In Coming Out of the Peoples Temple Closet and in Seeing the Faces, Laura Johnson Kohl paints a picture of her life in Jonestown and the personal and social traumas of trying to survive in the years that followed. But it is her poem Sisterhood that is the most personal, in which she speaks of the trust and mutual protection that comes with love, the caring and responding when asked and remaining available at all times, the ability to open up and love, even when there is no mention of blood ties. The poem concludes:

Sisterhood is the ability to open up and love.

We survivors of Peoples Temple, with all of our baggage

Want to give and take from this strong current

And that is why we gather together.

There is a clear delineation between the experiential narratives of the survivors of Jonestown, and the academicized writings about the events. The survivors of Jonestown are concerned with the human experience, the emotions, the relationships formed, the love, the work, the sacrifice, the friends and family, the living memories, the trauma, and the social good performed on a human level that are of value to working people. Academics, although performing an important task, are too often concerned with the larger social, political, and psychological issues. In doing so they may become detached from the realities of Jonestown as a working-class movement, and the needs and issues of its people. Academicizing the human needs of the Temple may have been one of the mistakes made by Jim Jones, in that he became detached from the people and the roots of the movement.

(The author thanks Rebecca Moore for her editorial suggestions in writing this article.)

References

Gardfrey, D. (October 2018). Two Poems. the jonestown report. Volume 20, A Special Section: 40 Years After Jonestown.

Harrison, M., F. (2004). Jim Jones and Black Worship Traditions. In R. Moore, A. B. Pinn, and M. R. Sawyer (Eds.) Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America. pp. 123-138. Indiana University Press.

Kohl, L., J. (October 2008). Seeing the Faces. the jonestown report. Volume 10, Personal Reflections.

Kohl, L., J. (October 2010). Coming Out of the Peoples Temple Closet. the jonestown report. Volume 12, Special Section: 1979 and Beyond.

Kohl, L., J. (October 2011). Sisterhood. the jonestown report. Volume 13, Personal Reflections.

O’Shea, T., B. (October 2010). Survivors’ Rights. the jonestown report. Volume 12, Personal Reflections.

Q 385. (May 3, 1978). Transcribed by Fielding McGehee.

Vilchez, J. (November 2007). Insight and Compassion: Vestiges of Peoples Temple. the jonestown report. Volume 9, Personal Reflections.

Vilchez, J. (October 2011). Remembering Liane. the jonestown report. Volume 13, Remembrances.

Vilchez, J. (October 2018). Caught Up in Living a Lie. the jonestown report. Volume 20, The People of Peoples Temple.