(Editor’s note: A chart with additional information on the Single Seniors of Jonestown appears as a PDF and as an Excel document. Both were prepared by Sarah Rex in conjunction with this article.)

One of the characteristics that differentiates Peoples Temple from many other new religious movements is the number of family units that filled its church pews in California and migrated to the jungle community of Jonestown. The number of individuals related to each other by blood or marriage in Jonestown – that is, of those for whom we have uncovered demographic information – was far greater than the number of people who were on their own.

Even some in Guyana who had no family ties within Jonestown – those described by this website as The Singles – had Temple relatives who were in the United States. This population includes children and young adults, among whom were: Daniel James Beck, the 12-year-old adopted son of Don and Bonnie Beck; Bof William Gallie, the 5-year-old son of Sue Ellen Williams and David Gallie; Monica Bagby, the 18-year-old daughter of Essie Clark; and Ricky Johnson, the 20-year-old son of Frances Johnson. It includes adults whose spouses were in the U.S., among whom were: Paula Adams, wife of Elton Adams; Daisy Lee, wife of Bobby Stroud; and Lee Ingram, husband of Sandra Bradshaw.

But by far, the greatest contingent of the Singles were elderly, a group of people who came to Peoples Temple – and to Jonestown – with no one, and who found a community there. These are the people of Jonestown who are the subject of this study.

*****

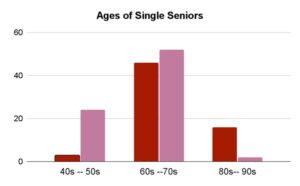

The Single Seniors of Jonestown are a difficult group of people to know definitively, because we can only really follow some of their backgrounds and stories of how they came to Peoples Temple. Just like with every aspect of research into Peoples Temple, the government and society of the early 1900’s makes finding accurate information about Black people from the South difficult. And the Single seniors of Peoples Temple were overwhelmingly Black (95.2%), women (92.5%), and from the South (68.7%). Most of these people were from poor areas and were children or grandchildren of freed enslaved people. So, for so many, there are no real records. In this article, we are going to explore what we do know. Even though we may not know too much about their backgrounds, what we do know is they found family in the Temple and in Jonestown, maybe not by blood but family nonetheless.

Peoples Temple was a Black church during its California years, with estimates that African-Americans comprised about 90% of its membership. While that percentage was significantly lower in Jonestown – about 69.2% – it was still a significant majority.

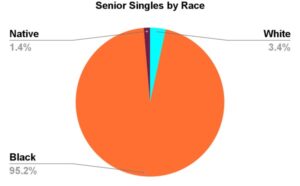

The most striking fact about the seniors of Jonestown is how much greater the percentage was for Blacks. Of the 143 identified Singles Seniors – defined here as Jonestown residents born before 1930 – 136, or 95.2%, were African Americans. (Another two people – or 1.4% – were Native American, with one of the two being Afro-Indigenous, a mix of Black and native.) The two factors that account for such a racial disparity are the laws, practices, customs and mores of the Jim Crow South; and the resultant Second Great Migration of Blacks from Southern States to the North and West between 1941 and 1970.

The most striking fact about the seniors of Jonestown is how much greater the percentage was for Blacks. Of the 143 identified Singles Seniors – defined here as Jonestown residents born before 1930 – 136, or 95.2%, were African Americans. (Another two people – or 1.4% – were Native American, with one of the two being Afro-Indigenous, a mix of Black and native.) The two factors that account for such a racial disparity are the laws, practices, customs and mores of the Jim Crow South; and the resultant Second Great Migration of Blacks from Southern States to the North and West between 1941 and 1970.

Jim Crow laws allowed state-sanctioned racial segregation. Enacted after the Reconstruction period after the Civil War – when the defeated Confederacy reasserted itself and clawed back much of its former power – the so-called “Black Codes” were effective in denying Black Americans the opportunity to vote, to live where they chose, to hold jobs, to receive a quality education, and otherwise to “rise above” their designated stations. As a result, the newly-freed Black Americans and their successive generations found themselves stuck in endless cycles of poverty and lack of opportunity.

In an attempt to try to escape the institutionalized violence and racism, many Blacks moved North and West in search of better opportunities. There were two movements known as Great Migrations: the First between 1910 and 1930, and the Second – which would have included those Blacks who eventually joined Peoples Temple – beginning with the outbreak of World War II in 1941 and extending to 1970. Unfortunately, many Northern states practiced de facto segregation by ghettoizing Black Americans into the inner cities – part of a process that became known as redlining – and granting their schools and local governments less state and federal funding. Blacks also paid home loans at exorbitant interest rates for dilapidated homes.

On a positive note, the concentration of Blacks in the core of large American cities led to cultural and societal revolutions. Places like Harlem in New York became cultural hubs. But probably the greatest result of the isolation and concentration of Blacks in these areas was the safety and mutual protection they found in the strength of their numbers.

A search for the background records and census locations of the seniors inside Peoples Temple reveals this Great Migration in real time. Many examples exist, but three groups will suffice as illustrative.

The first group comprises Inez Stricklin Conedy, Beatrice Dawkins and Mahaley Johnson.

- Born in Arkansas in 1909, Inez is presumed to have married the first time in Arkansas, as there is no marriage record in California for her. By the time of the 1950 census, she was living in Oakland, California. After she and her first husband divorced, she remarried in 1963, but eventually divorced again. By 1968, she was living in Palo Alto. She migrated to Jonestown in July 1977, where she was a kitchen worker and rice sorter who lived in Dorm 2.

- Beatrice Dawkins was born in Mississippi in 1918, and was married and living with her husband in Missouri when her husband died in 1961. She then moved to California and worked as a cook in a household before joining the Los Angeles Temple, and then moving to Jonestown in August 1977. Like Inez, she was a kitchen worker and rice sorter who lived in Dorm 2.

- The final member of this group was their friend Mahaley Johnson – also a kitchen worker and rice sorter who lived in Dorm 2 – who was born in rural Upshur County in eastern Texas in 1910. Records are scant on her – we do know she married while still in Texas – but by the 1970’s, she was living in Los Angeles with her children. She arrived in Jonestown in August 1977.

The next pair is Lucille Payney and Carrie Ola Langston.

- Lucille Payney was born in Illinois in 1899, married, and lived with her husband in California during the 1950’s. Her husband worked as a meat packer before his death in 1969. She went to Jonestown in August 1977, where she worked as a receptionist on the medical staff, in the Senior Citizen Center, and as a Rice Sorter.

- Carrie Langston was born in Diretta, Louisiana in 1923, where she married and had at least one son, who died while the family was still there. She and her husband had moved California by the late 50’s. Like Lucille, Carrie was on the medical staff of the senior center, and the two shared living space in one of the cottages.

The final pair comprises two Black men – Earl Luches Johnson and Theo Williams Jr. – who both lived in Dorm 1 in Jonestown. Although they had very different jobs within Jonestown – Theo was a rice sorter and Earl was a field worker – their backgrounds and former residences are their common factors.

- Earl was born in 1912 and raised in Eufaula, Oklahoma, before he moved to California by 1950 with his wife.

- Theo Williams Jr was born in Beaumont, Texas in 1915, married in 1944, and worked as a farmer and sharecropper. He had moved to California by the 1960’s.

Each of these groups shows the commonality within them: they moved for a better opportunity, and found like individuals with shared experiences within Peoples Temple.

*****

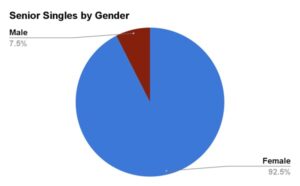

Like the racial component of the Single Seniors being overwhelmingly Black, their gender is overwhelmingly female, at 95.7 %. Also as with the racial component, the different reasons for this can be found in their background.

Like the racial component of the Single Seniors being overwhelmingly Black, their gender is overwhelmingly female, at 95.7 %. Also as with the racial component, the different reasons for this can be found in their background.

Historically, women are the backbone of most communities. They give birth to, provide primary care for, and educate the children, and are the emotional and physical support of their families. Even during the years of slavery, as Black women shouldered the major responsibility for the household and family, they were also expected to work at the same pace along with Black men. Because of their historic role in society, women have always thrived with the backing of other women in their community. It’s where the phrase – “It takes a village to raise a child” – originates. The Black communities between the 1930’s and 1960’s were no different. Women were a major factor and voice in the fight for racial equality. With all of these demands, the human desire for community turned into a need for that community support and help. Women found that in Peoples Temple.

Three groups of women illustrate the “found family” of women in Jonestown.

- The first is Hazel Horne, Mary Mayshack and Lillian Boyd Alexander. All were Black women, around the same age – Hazel was 63, Mary was 73, and Lillian was 72 at the time of their deaths – who seemed to do everything together. They all worked in the vegetable stand and the kitchen – both in Peoples Temple in California and in Jonestown – and lived in Dorm 5 together. Not much is known about their lives before they joined Peoples Temple, but it is apparent they built community where they lived and worked together and found people like them to lean on.

- The next group consists of three Black Southern women named Rosa Mae Hines, Pearl Land and Gladys Ammie Roberts. All three were in their 70’s, lived in Dorm 4 and worked as Rice Sorters in Jonestown. Rosa and Pearl were also divorced. Although, we know a bit more about their lives before the Temple than the first group, it is still clear that the community they built together was a close one.

- The final examples are Mary Be Baldwin, Isabell Minnie Davis, Ruth Whiteside Lowery and Roberta Lee Wade. All four were Black women from the South who worked as rice sorters together in Jonestown. But they had something else in common: All of them had suffered through the deaths of most or all of their immediate families shortly before entering the Temple. Their loss of their first family community must have been devastating, but it seems as though they found comfort in the Temple with women who had been through the same experience.

*****

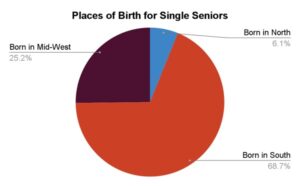

The birthplaces of the Single Seniors offers a bit more variety. Although most were in the South (68.7%), the Midwest made up a significant portion (25.2%). One reason for this geographic diversity likely stems from the fact that Peoples Temple had Midwestern roots of its own, having been founded in Indianapolis in the 1950’s. Known at the time as Wings of Deliverance, Peoples Temple was one of the only fully desegregated churches in the state. It’s easy to see how a number of Blacks – who would have been part of Peoples Temple long enough to become seniors – found their way to the church and found the refuge of a community there.

The birthplaces of the Single Seniors offers a bit more variety. Although most were in the South (68.7%), the Midwest made up a significant portion (25.2%). One reason for this geographic diversity likely stems from the fact that Peoples Temple had Midwestern roots of its own, having been founded in Indianapolis in the 1950’s. Known at the time as Wings of Deliverance, Peoples Temple was one of the only fully desegregated churches in the state. It’s easy to see how a number of Blacks – who would have been part of Peoples Temple long enough to become seniors – found their way to the church and found the refuge of a community there.

Emma Addie Kennedy and Odenia Adams Roberson, for example, were Black women from the South who lived in Dorm 4 and did letter-writing for the Correspondence of Life in Jonestown together. Emma was born in 1911 in Georgia, and Odenia was born in 1905 in Louisiana, two states with Jim Crow laws. They likely saw the world through the same lens and forged a bond in their shared experiences.

Emma Addie Kennedy and Odenia Adams Roberson, for example, were Black women from the South who lived in Dorm 4 and did letter-writing for the Correspondence of Life in Jonestown together. Emma was born in 1911 in Georgia, and Odenia was born in 1905 in Louisiana, two states with Jim Crow laws. They likely saw the world through the same lens and forged a bond in their shared experiences.- Millie Stearn Cunningham and Nevada Harris were Black women from Texas, born in 1904 and 1910 respectively, who worked in the bakery together. While they lived in different dorms, the bond they shared is still clear.

- Finally, consider “The Fannies”: Fannie Ford and Fannie Alberta Jordan. Fannie Ford is a bit outside of the age group laid out in this study (born in 1934, she is about four years too young), however, she was kept in because she fit all other “Single Seniors” criteria, being a Black woman from the South with no other family inside of Peoples Temple. She also seemed to have worked with and spent time with the Seniors. Both were Black women from the deep South, Ford from Mississippi and Jordan from Louisiana. They were mentioned often as friends and gossip buddies in Edith Roller’s Journals and other Temple documents. They apparently also shared a great passion for their work in the Herbal Kitchen, if the praises in Agricultural Reports for their creation of truly great dishes is any indication.

*****

Yet another point for self-grouping for seniors in Peoples Temple was a past association they had before joining Jim Jones and his church. This is the International Peace Movement of Father Divine who preached racial inclusion and diversity to his predominantly Black congregations – principally in New York and Philadelphia – for 50 years before his death in 1965. He had a predominantly Black following at first that grew more diverse until his death in 1968. (For the most complete background of members of Peoples Temple who had once been in Father Divine’s Peace Mission, see “Ever Faithful” by E. Black.)

There were numerous people, almost exclusively Black women, who eventually joined the Temple, including four who died in Jonestown. Their experiences with the Peace Mission had already exposed the to the benefits and solidarity of communal living. While all four were beloved members of the Temple, they retained a sense of that previous experience which remained important to them.

- Two of them were Ever Rejoicing and Love Life Lowe, who were 97 and 89 respectively. Mother Rejoicing was born Amanda Poindexter in Pittsylvania County, Virginia to freed enslaved parents, Peter and Sally Poindexter. She married Joseph Williams, who died at an unknown date. Her close friend, Love Life Lowe seemed to be her opposite in many ways, except for their Father Divine background. Mother Lowe was born Georgia Belle Owens in Kansas City, Missouri to George Owens and Sally Knox. She lived in Washington, D.C., where she married a man named Anderson Lowe, and when they divorced in 1935, she joined Father Divine’s movement. Despite their ages, they were both listed as workers in the Senior Citizen Center in Jonestown.

- Mary Love Black and Heavenly Love – also former followers of Father Divine – were also very close, even though at ages 57 and 78 respectively, they were a generation apart. Both worked as letter-writers for the Correspondence for Life. Although not much is known about their backgrounds, Edith Roller’s Journalsreveal how beloved they both were in Peoples Temple and in Jonestown. It was an attribute that all former members of the Peace Mission seemed to have in common.

*****

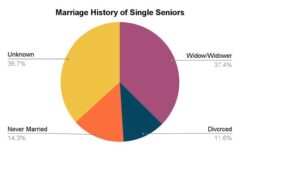

The final area of the lives of the Single Seniors worthy of study is their marital history, even if it is the puzzle with the most missing pieces. As the accompanying chart shows, neither Temple nor census records offer the status of more than a third of them. Of those we do know, however, about 60% were widowed, and most were Blacks who migrated during the Second Great Migration, and there is no reason to believe that statistic would change much as additional information comes to light.

The final area of the lives of the Single Seniors worthy of study is their marital history, even if it is the puzzle with the most missing pieces. As the accompanying chart shows, neither Temple nor census records offer the status of more than a third of them. Of those we do know, however, about 60% were widowed, and most were Blacks who migrated during the Second Great Migration, and there is no reason to believe that statistic would change much as additional information comes to light.

Consider Florine Dyson and Oreen Poplin, friends who roomed in the same dorm. Florine was born in Virginia in 1890 and migrated with her husband James to New York. They both were in the Peace Mission until the deaths both of James and Father Divine in 1965; soon afterwards, Florine joined Peoples Temple. Oreen was born in Texas in 1904, and in a common law marriage to Earl Poplin until his death in 1977. They had joined Peoples Temple together, and after he died, she remained in the community that supported her.

These stories are not unique. So many widows in the Temple – most of them seniors by the time they died in Jonestown – had migrated with their husbands for better opportunities in the North, leaving behind the family and life they knew. The deaths of their husbands, and the social partnership – and often the financial support – they had in marriage, left them searching for the safety net that they found in Peoples Temple.

Widowhood was not the only marital status that existed within the Temple. Among the 11.6% of the senior population who were divorced, two were Black men, Samuel Moses Anderson and Levatus V. McKinnis. Both were born in Mississippi – Samuel in 1911 and Levatus in 1906 – both married there, and both moved to California separately from their ex-wives after their divorces. In Jonestown, they both worked security and lived in Cottage 9.

The never-married seniors – comprising 14.3% – represent more of a challenge and some educated assumptions. All are women, all have their maiden names, and none have marriage or divorce records that we can trace.

Lillian Malloy and Eura Lee Moses provide examples of this. Both were Black women from the South around the same age – Lillian was 73 when she died, and Eura Lee was 79 – and neither married. They were friends and roommates, but just as important, they found like-minded people within the Temple and built their bonds there. The community they never had in marriage, they found with each other.

*****

This study of the Single Seniors who died in Jonestown – and in fact, any study of seniors in Jonestown – is not complete and will almost certainly never be definitive. The record-keeping on Black populations from the South, which covers an overwhelmingly high number of these seniors, was shoddy at best, and sometimes culled from county records or never kept. Nevertheless, we know more records are still out there that will fill in the gaps, and we continue to look for them.

In the meantime, we can draw some general conclusions about the Single Seniors. Many of them were Blacks born in the South who escaped Jim Crow laws during the Second Great Migration and who lost their original families through death or separation.

Other conclusions we can draw encompass the entire Temple membership. Like so many who joined, the initial attraction may have been Jim Jones, but the bonds the members forged – the bonds that let them stay – were not with the Temple leadership, but with the other people with whom they created relationships. They all found a group of thousands of people working together for a common goal and with common respect and love for each other.

In these ways, then, many members – not just the Single Seniors – were like Julie Birkley, a 69-year-old Black woman from Alabama who was remembered fondly as a constant calm presence within the Temple. Her beautiful singing voice earned her a place in the Peoples Temple choir. Not much is known about her life before the Temple. But thanks to Temple records and survivor stories, we know she was a kind and vibrant part of the community that she joined and called home.

In these ways, then, many members – not just the Single Seniors – were like Julie Birkley, a 69-year-old Black woman from Alabama who was remembered fondly as a constant calm presence within the Temple. Her beautiful singing voice earned her a place in the Peoples Temple choir. Not much is known about her life before the Temple. But thanks to Temple records and survivor stories, we know she was a kind and vibrant part of the community that she joined and called home.

(Sarah Rex is a 30-year-old epileptic disabled mother of two children. Her other article in this edition of the jonestown report is The People of Peoples Temple. She can be reached at Sarahelizabethrex@gmail.com.)