Memories of an Old Friend

Let’s talk about the Touchette brothers. One brother survived; the other did not. Albert Touchette’s life was cut short nearly 50 years ago in Guyana – a place he and his brother, Michael, envisioned as a refuge from American society. Together with their fellow pioneers, the brothers built a community for 1000 people in a Guyana jungle where they staked their dreams for a better future.

Then, one day, it was gone.

The history of Jonestown cannot be told without acknowledging the Touchettes, and their story inevitably leads us back to where it all began – Indianapolis, Indiana – during the turbulent 1960s.

Except it was not turbulent, at least not in the tidy neighborhood where the Touchettes lived, where manicured lawns and cookie-cutter houses belied the social, economic, and cultural upheavals that swept through the rest of the country. They also looked the part of what many would now consider an idealized and unattainable image of America.

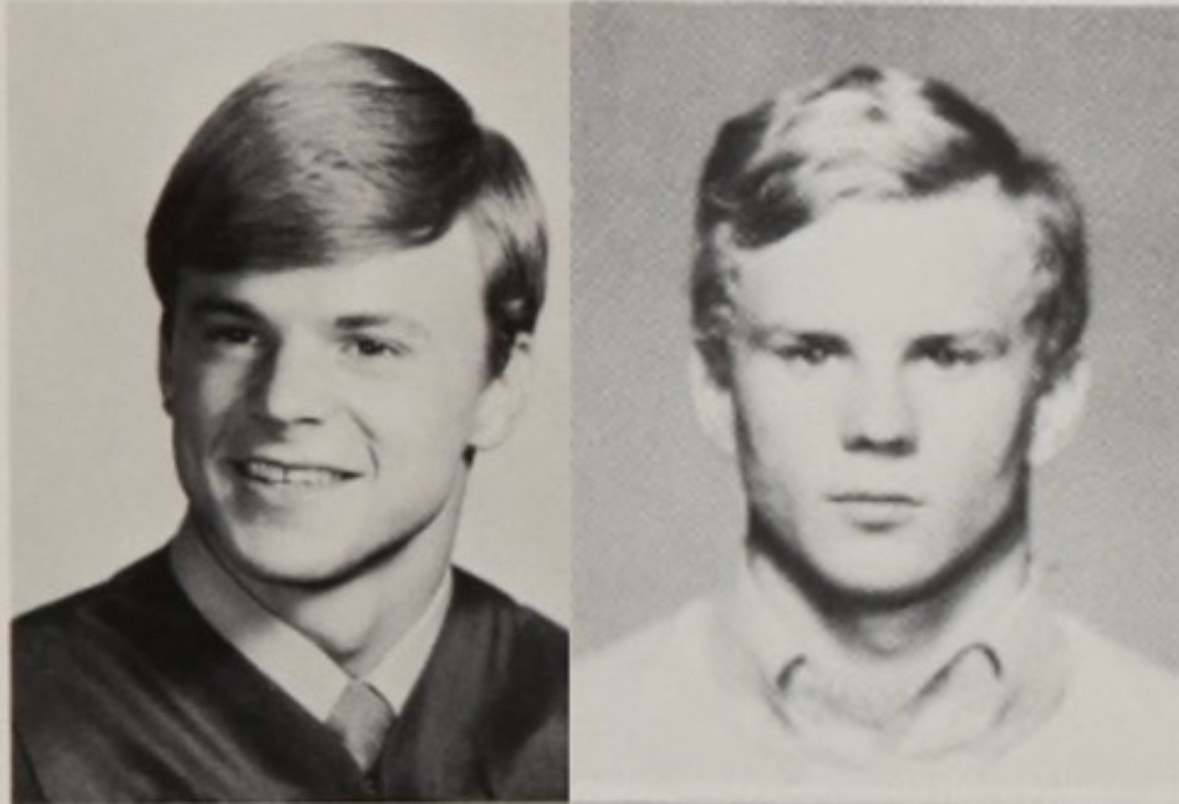

All four children of Charlie and Joyce Touchette – Mickey Jean, Michael, Albert, and Michelle – were clean-cut and well-groomed.

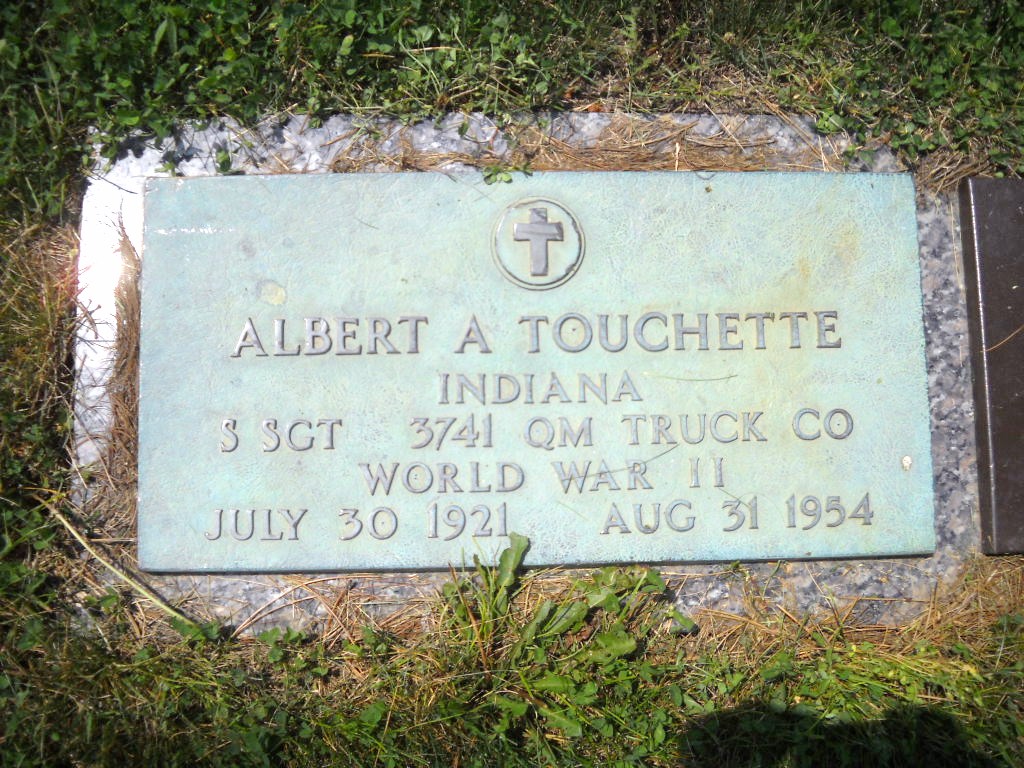

Tragedy first struck the family on August 31, 1954, when Albert Ardell Touchette, who had served in World War II as a Staff Sergeant, died less than two weeks before the birth of his nephew. In honor of his late brother, Charlie named his newborn son after him, perhaps in the hope that someday he would grow up to be just like his uncle: a brave soldier, a hero.

But the younger Albert, whose short life was full of potential and promise, died in Jonestown just two months after his 24th birthday.

Beyond their shared name, lineage, and untimely deaths, another fact linked the two Alberts. Indianapolis was where the elder Touchette is buried and where the younger one was born.

An All-American Family

In the 1960s, the Touchettes lived in a delightful house on Frontenac Road, in a clean, well-kept neighborhood where everyone knew each other.

Denise McDowell, a childhood friend of the Touchettes, proudly declares that their neighborhood was home to 37 houses and 73 children. They lived just a short distance from school #98, where Mike and Albert attended classes along with their younger sister, Michelle. In fact, living so close to the school allowed the kids to dash home during breaks for a quick meal before racing back for their next class.

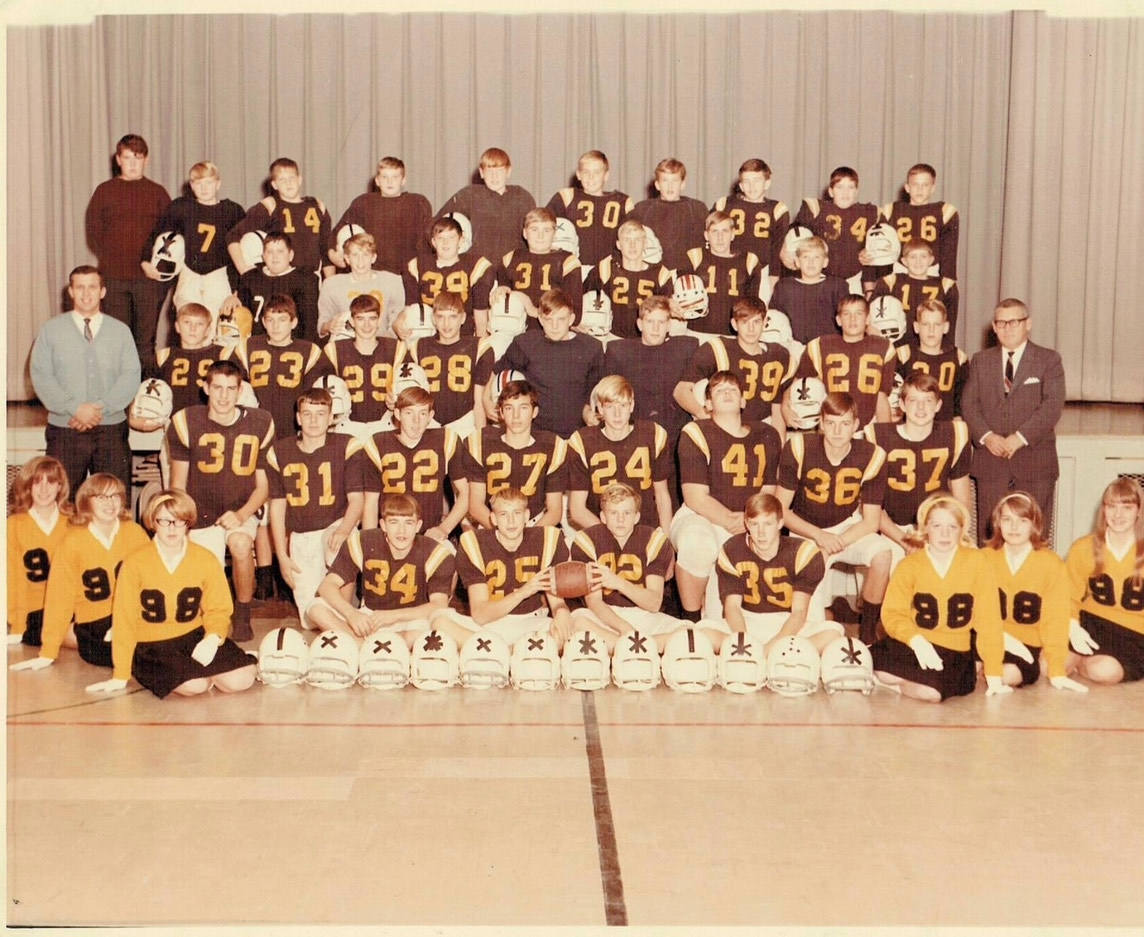

“That meant quite a few of the neighborhood kids were very athletic – Mike and Albert especially – and very visible to the school staff.”

Both brothers excelled in sports, which made them quite popular with their peers. As an old schoolmate attested, “I went to high school with Al, class of 1972. I was not on his social level, but I did take some guff from him for being a nerd.”

Albert might have teased a “nerd” or two, but he was a bit of a whiz himself. His teachers in middle school recognized his intellectual capabilities early on and placed him in a split-grade classroom with other achievers. On top of his academic accomplishments, he played football and basketball for his school.

“Albert had to be achieving at a considerably higher level than many of his friends – those not in his split class – so for him to maintain his accolades and spend time in sports, he had to be gifted and someone who could push himself to fulfill both requirements,” McDowell recalls. “Enter an achieving older brother whose athletic ability shines in multiple sports – and his own scholastic and athletic demands became way more complex to keep up. These years are when I remember Charlie doing a lot of shouting.”

After the tragedy in Jonestown, Albert’s grandmother, Mrs. Emily Touchette, paid tribute to her late grandson. In an interview with the Indianapolis Star, she remembered Albert as “very, very intelligent, but ashamed of it. He didn’t want to excel over the other boys.”

A former teacher described him in the same interview as “a happy-go-lucky guy. Always a smile, friendly, extremely personable.”

In the wake of Jonestown, Mrs. Touchette bitterly lamented the loss of her family and the life they once shared. “We had such a beautiful family life until that man [the Rev. Jones] came along. They all enjoyed swimming.”

From the outside, it appeared like the Touchettes had it all: an enviable family life that played out like a wholesome TV show, complete with corny clichés and predictable storylines. Charlie was a successful salesman, Joyce was a wonderful hostess, and all four kids were involved in cheerleading, football, basketball, or camping.

As McDowell describes it, their neighborhood was home to many athletically gifted teens: football players, cheerleaders, band members, and members of the cheer squad. That included the Touchette brothers – “our football stars,” McDowell declares – and the boundless energy and determination they brought to the field would later take them thousands of miles to South America.

Life on Frontenac Road

The string of charming tract houses with manicured lawns formed a U-shape along Frontenac Road, where at least ten families embraced an open-door policy. The trust between neighbors was so high that walking into a family’s home and asking to use their restroom was not out of the ordinary.

“We either walked or rode bikes everywhere,” McDowell remembers. “And you did not need bike locks – no one tried stealing them. You threw them on the front lawn in between use.”

It was the Touchettes’ home where McDowell, the third oldest of eight children, sought refuge whenever she felt sick or unwell.

Joyce was her confidante in these private matters – a gentle, motherly figure who treated her as if she were one of her own daughters. “I loved sitting and talking to her,” she fondly recalls. “I ran track and placed first in basketball in 8th grade – Joyce was the one who hugged and congratulated me like I was her daughter (my mom had just left the event).”

McDowell also considered Joyce’s youngest, Michelle, her best friend in those days. They spent Saturday mornings playing on the same bowling team and spent every weekend in the summer camping together. “Michelle was my summer buddy. She went camping every weekend with us and helped me on the nanny job… Charlie used to tease her that she was starting to take on the traits of a McDowell.”

When Mickey was away, their freckled, red-haired young neighbor would spend the night with her best friend and the rest of the family. Dinnertime called for a seat at the round table with a Lazy Susan in the middle, where everyone gathered to eat and catch up with one another.

Today, McDowell regrets putting her friendship with Michelle on the back burner. She was two years older and juggling the demands of school alongside her responsibilities at home.

“Time with her took a backseat to school, and that is why summers were so important.”

A Simpler Time

The Touchettes and their neighbors fostered genuine relationships with each other by taking part in fun recreational activities.

On weeknights, the Touchettes, McDowells, and their friends spent most of their time outdoors until the streetlight came on. Weekends, however, gave the rambunctious kids a little more freedom. That is, until Charlie Touchette’s whistle echoed across the street or the front light of the McDowells’ home flashed twice. “You never wanted a third flash to happen.”

There was an innocence to life in those hazy summer days that was gradually lost over time. Now, it is nothing more than a fleeting moment in the town’s history, a beautiful memory tucked away in the back of McDowell’s mind.

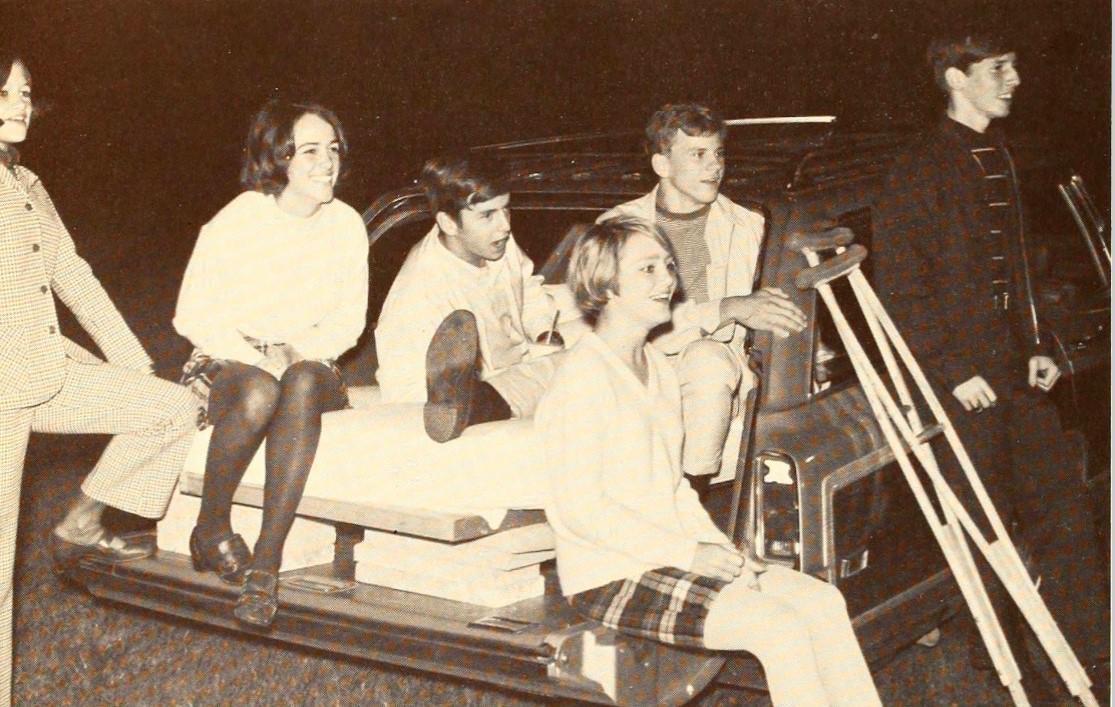

As she remembers it, sock hop parties with live music occurred once a month. A square ball tournament took place once a weekend, reflecting the neighborhood’s passion for sports. On any given day back then, a band played on the patio of the McDowell home or a game of baseball took place in their yard.

But the most exciting activity was reserved for Sunday nights, when the McDowell family would load up their van and station wagon with kids from the neighborhood – Albert and Michelle included – for a 40-minute drive to the Rainbo Roller Rink, a popular skating venue with a distinctive rainbow-colored trim along its upper facade. Anyone who made it before the McDowells departed was welcome to squeeze into one of their cars and join the road trip to Noblesville.

The Rainbo was the place where childhood friendships were made, boosted by snack bar treats, lively music, and skating to the Hokey-Pokey. The Touchettes, McDowells, and their classmates from school #98 would lace up their rollerskates and rush onto the rink as the organ player joyfully announced, “It’s an all skate, all skate!”

When families were not making the long drive to Noblesville for an all-night skating party, there was a community pool nearby on 38th Street where social activities were held. In fact, the Northeastwood Club was a popular hub where the neighborhood kids gathered for teen parties and swimming lessons.

In a remembrance written for Michelle on this site, an old classmate recalled seeing Mike and Albert there: “I remember her brothers were very good swimmers and divers at the Northeastwood Swimming pool and enjoyed watching them dive.”

On other nights, the Touchettes simply stayed home. They played a variety of games – ping-pong, baseball, basketball, pool – while Charlie and Joyce, along with the family who lived behind their house, pulled out their lawn chairs and watched the kids play. Mike, Albert, and a few friends took part in the backyard games as the adults sipped on their evening cocktails.

The Touchettes could be quite intense, McDowell admits. That was particularly true of Charlie, when the kids were involved in a competitive game of sports.

“Charlie and basketball mostly – I remember getting yelled at (just like he did Michelle) when I didn’t react the way he wanted me to. I played volleyball and basketball in junior high and high school, thanks to him.”

McDowell feels that Albert took the brunt of Charlie’s biting criticism. Nevertheless, there were no outward signs of violence, and the Touchettes seemed like any other family living on Frontenac Road.

Life Lessons

While their neighborhood may not have been rough and tumble, it did provide its residents with some dangerous and exciting moments.

Every now and then, a few pigs would break free from their pens on the farm located behind the McDowell home. If there was ever a time for the neighborhood boys to prove to themselves – and each other – that they had finally become men, this was it. Mike, Albert, and the rest of their pack would round up the four-legged runaways and bring them back home. One can imagine how the brothers, ever steadfast in overcoming difficult tasks, welcomed this challenge.

“I remember laughing until I peed my pants watching Albert wrestle a pig to the ground so it could be taken back home.”

“He made fun of me forever,” McDowell recalls. “I always loved – I am using an adult term, not an adolescent one – being around Albert; he was a good friend who looked out for others. He was loyal, compassionate, and someone that you wanted in your ‘Red rover, red rover – send Albert right over’ line!”

Glory Days

While Albert was heavily involved in sports, even dating a cheerleader (“We used to kid them Al and Al,” McDowell says), the true star athlete in the family – the one whose achievements the school chose to splash across its yearbook pages year after year – was his brother Michael.

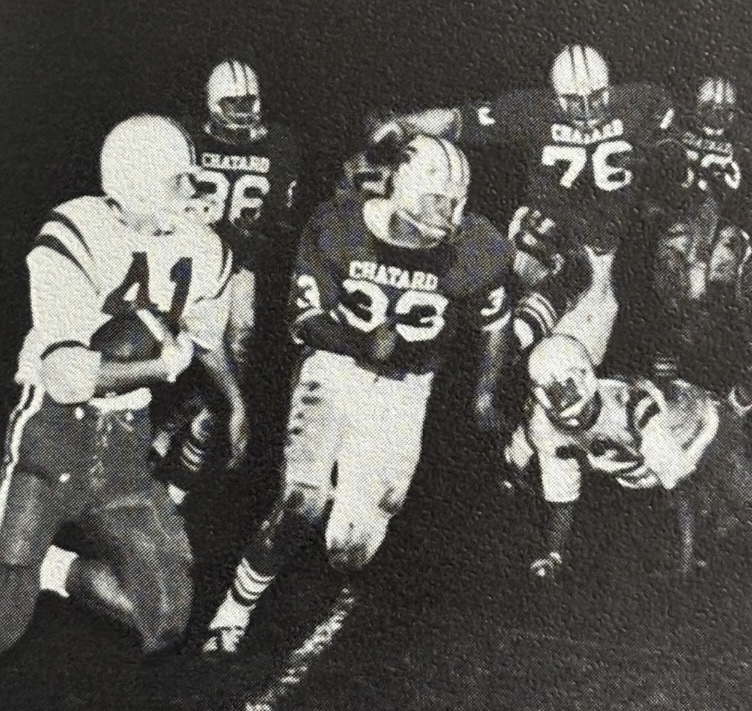

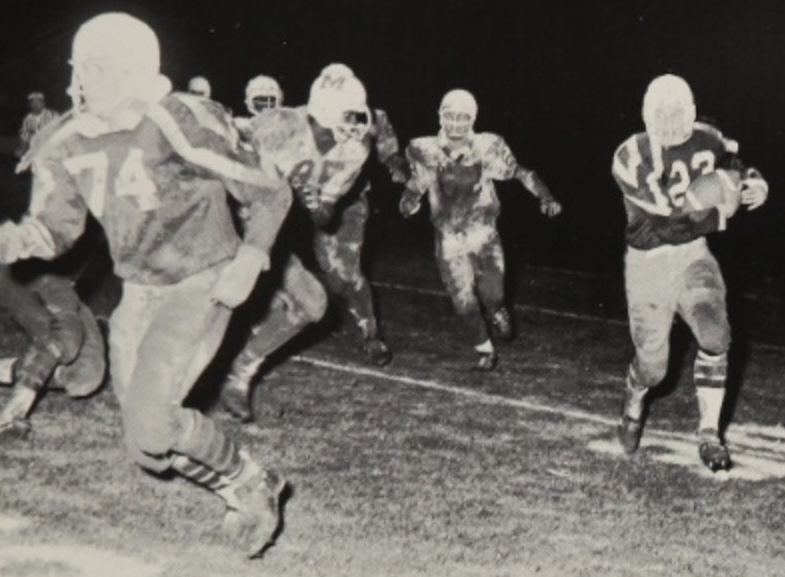

In the 1968 Marhiscan yearbook, Mike, then a freshman in high school, was listed as a Booster Patriot. The following year, he secured his position as the school’s football star, appearing in no fewer than three glossy pictures on the 1969 Athletics section. It was almost as if his arrival had ushered in a new era for the team, as the yearbook proudly declared: The Pats Aren’t ‘Patsies’ Anymore.

The dramatic retelling of that thrilling Indianapolis high school football season didn’t end there.

Facing a tough schedule head-on, the injury riddled footballers surprised four teams this year with brilliant wins. A coach’s dream of all returning lettermen made this season’s prospects look bright…

Mike Touchette, running hard before his injury in Terre Haute, outruns his tough Chatard opponents.

The next year, Mike was once again featured in the school’s 1970 yearbook, now immortalized in Pats history.

[S]peed merchant Mike Touchette races downfield for valuable yardage.

Mike suffered an injury that put a halt to his football career. That, however, did not dampen his shine. As part of the track team, he set a new school record in 1969, completing the 100-yard dash in a little over ten seconds.

New Beginnings

Emily Touchette told the Indianapolis Star that Charlie and Joyce sold everything they owned and moved to California in 1970 to join Peoples Temple. “I used to tell him those fly-by-night religions never last,” she told the newspaper shortly after the tragedy. “We all talked and prayed and begged and tried to get him out of it.”

The family did their best to adjust to a new life in California. However, it was not without its challenges. Although Mike played football at his new high school, the change proved to be too much. The new school, his new coach, and his fractured relationship with Charlie ended his desire to play sports.

Mike remembers his feelings at the time: “As far as I know, my athletic career, if you want to call it that, was over when I joined Peoples Temple in 1971. I no longer had desire to play football or run track or whatever. I did not like the high school that I went to in California, I did not like the coach. There were a lot of things I did not like about it. When they had me in a room with a bunch of recruits from different colleges, and when they told me that I was going to have to go to a junior college with my present head coach, I said ‘no, I’m done’ and I walked out of the room. I just had enough of it.”

Instead of dancing at sock hop parties, chasing pigs, and basking in football glory, the Touchettes’ relatively short time living in California was marked by bus rides, communal living, and orchestrated protests. In a way, it began the loss of innocence for the brothers.

As Mike recalls, “It was really an eye-opening experience, because the first day of school, I had some guys that I had met, and they picked me up and took me to school. When we parked the car and got out of the car, all you could do was smell weed. I had no clue what it was, so it was an eye-opening experience moving to California.”

Mike eventually adjusted to life in the Golden State. He married Debbie Ijames and forged genuine friendships with people from all walks of life. The Temple had many faults, but it was good at hiding them. It was also one of the few churches in America that dared to open its doors to absolutely everyone, providing those who had been rejected by society with a place to belong. Mike, who at a young age was taught the principles of equality and integration, embraced this change.

Even in the safety of their Indianapolis suburban bubble, Joyce Touchette made sure that her four children understood the social injustice and racial disparities that existed beyond their idyllic neighborhood. “My mother raised us where there was no color,” Mike told Katherine Klapperich in a 2021 interview.

This philosophy seemed just as deeply ingrained in his brother Albert. In a security team report recovered by the FBI after Jonestown, Albert conveyed his hatred for “racism and fascism,” and expressed guilt “for the years of oppression white people have forced on black people.”

She may not have realized it then, but Joyce was preparing her children for life in the Golden State and beyond.

Old Friendships Lost

McDowell confirms that after exchanging a few letters with Michelle, she lost touch with the Touchettes. “Michelle and I wrote a few times, but she was very involved in the church there and the letters dwindled down and finally ceased. It was too expensive to call long distance, so we lost touch.”

If there is anything life guarantees, it is change – and with it comes the loss of old friendships. While it cannot be known for certain how Albert felt about leaving his friends behind in Indianapolis, we do know that, at least for a time, his old friends had not forgotten him. In the 1971 edition of the Marhiscan yearbook, they dedicated a page to Albert titled “BIG AL – OUR PAL”.

In the years after Jonestown, the families on Frontenac Road gradually moved out, starting new lives and new jobs elsewhere. The schools they once attended have since closed, leaving the memories of the Touchettes’ scholastic and athletic achievements preserved in yellowing yearbook pages. Sock hop parties were a thing of the past, much like roller rinks.

As for the old neighborhood – it is still there, a little worn, but trying its best to carry on like the rest of America.

Sources:

Emily Touchette and Faculty Members Interview with The Indianapolis Star, November 22, 1978.

Dan Young Remembrance Entry for Albert Touchette

Anonymous Remembrance Entry for Michelle Touchette: “I remember her brothers were very good swimmers.”

Rainbo Roller Skating Rink: https://forgottenrollerrinksofthepast.com/Rainbo IN.html This site is currently offline.

An Interview with Mike Touchette, by Katherine Klapperich, The Jonestown Institute.

Mike Touchette, Booster Patriot: 1968 Marhiscan Yearbook, Page 136

Mike Touchette Football Photos, “Pats Aren’t Patsies Anymore”: 1969 Marhiscan Yearbook, Pages 68-69

Mike Touchette, Speed Merchant: 1970 Marhiscan Yearbook, Page 76

Mike Touchette, Track New School Records: 1971 Marhiscan Yearbook, Page 76

“BIG AL – OUR PAL” Dedication to Albert Touchette: 1971 Marhiscan Yearbook, Page 153

Al Touchette, S.A.T. Personal Reports, The Jonestown Institute.

Albert Ardell Touchette, Uncle of Albert Touchette, Find-A-Grave.

(Danielle Redifer became interested in the early years of Jonestown and the people who built it. She maintains an account on the Jonestown Pioneers on Instagram that documents the work of the pioneers, and honors the victims of the tragedy: https://www.instagram.com/thejonestownpioneers/. She is also the author of Chronicling the History of the Pioneers in Jonestown. She lives in Alabama with her husband.)