A Conversation with Stephan Jones and Mike Touchette

1974: The Pioneers Arrive in Guyana

When 21-year-old Michael Touchette first saw the jungle stretching out alongside the road between Port Kaituma and Matthews Ridge, there was nothing to indicate that within three years, there would be a road leading into a community of 1000 people, and that he would have been an integral part in building it. Trees rose above him like outstretched hands, their foliage clustered into thick canopies that shielded him from the sun. There was already a crew of Amerindians working tirelessly to clear the jungle, but most of it remained untamed and inhospitable.

Mike disappeared into the thick vegetation until he reached a clearing, where the sky seemed to open above him. He was stunned.

Nearly 50 years later, he reminisces about that moment as his friend, Stephan Jones, the natural-born son of Jim and Marceline Jones, quietly listens.

“I was in awe,” Mike begins. “The first time I went in there, it was just a footpath in the jungle. I consider it a privilege. I got to go in and see the progress of the Amerindians, who had cut the trees down. I got to see all that happen! I don’t think you can really appreciate how thick and how dense the jungle is unless you go into it. You’re walking through jungle, and then you walk into a clearing. It’s like the sky opened up in a way. During the day in the jungle, you’re shaded from the sun, you don’t even hardly see the sun.

“It was amazing to me to have that experience,” Mike adds. “And it’s still very dear to me.”

In early 1974, a handful of young men who referred to themselves as the pioneers – Mike Touchette, Phil Blakey, Tim Swinney, Greg Frost, Les Mathison, and Anthony Simon – arrived in Guyana, a country in South America known for its majestic waterfalls and winding rivers. They made the 24-hour journey by boat from the nation’s capital of Georgetown to Port Kaituma, a village on the banks of the Kaituma River. There they took up residence in old barracks that were built by the government for an unsuccessful farming project – an antecedent to the Temple’s agricultural venture.

Every day, Mike and his compatriots traveled the six miles from Port Kaituma to the point of entry into the jungle, and then walked the three-and-a-half-mile trail to reach the area that eventually became Jonestown. For most of the first settlers, living in Guyana was a thrilling adventure. Rather the dangers of the jungle frightening them, they were fascinated.

Going down there, even though I had no clue or anything about it, it was like a dream come true to me. I’ve always been an outdoor person. I’ve always enjoyed going out into the woods. So I got to see Jonestown from start to finish, and it was an amazing time.

Throughout the process, the pioneers worked with Bernie Matthews, the government surveyor tasked with assessing the site. Matthews explained his process for selecting suitable land for Jonestown’s development: he chose elevated areas along the road that avoided low, swampy spots. This provided them with drier, more stable ground to work on.

By the time the pioneers arrived in Guyana, work on the settlement had already begun. Working by hand, the Amerindians cleared dense jungle, cutting down trees and thick serpentine vines. These were left to dry on the ground, piled into windrows and burned.

Evolution of Jonestown

The three-mile path to the settlement was slowly widened with 1000 feet of cleared land on either side. Guided by stakes planted in the path’s centerline, Mike learned how to operate a bulldozer and began to remove debris. Just a few years after leaving an idyllic life in Indianapolis, 21-year-old Michael Touchette was building the road to Jonestown.

There are many pictures of the pioneers from those early years. In nearly all of them, Mike is sitting on a muddy Caterpillar machine. He ignores the camera, focusing only on the incredible task that lies ahead of him. A few more photographs taken from a distance capture a tiny figure in the vehicle, both man and machine nearly lost in the chaotic mixture of fallen trees, muddy stumps, and tangled roots. That’s Mike, too.

Decades later, Mike talks about his old bulldozer with a sense of awe and longing, as if he were remembering an old friend:

I’ve always wanted to operate heavy equipment, like a bulldozer. Even though I lied through my teeth about it, I’ve never gotten on one of those machines before in my whole life, until the first day that we got our bulldozer there. It was something about it. It was like natural to me. It was like the machine was an extension to my soul.

“He did drive a bulldozer like it was an extension of him,” Stephan confirms, then recalls the moment Mike taught him how to operate the muddy machine himself.

The way he did that is he put me in a bulldozer, showed me how the leverage works, and pointed at a pile of seashells and said, ‘make that flat.’ And man, that was a painful experience, but by the time I was done, I could drive a bulldozer.

The two of them worked as a team.

I remember operating a bulldozer side-by-side with Mike, as we were pushing the trees that we’d felled months earlier and then burned. At one point, he climbed out of the bulldozer as it was pushing a big load, stood on the roof of the bulldozer, and put his fists in the air as it was pushing trees down this steep bank.

The road they constructed ended at the center of the clearing, expanded by the Amerindians who had removed the vegetation from an additional 30 acres. They erected a simple building with six beds and a makeshift stove and used it as their temporary living quarters. As Mike described it:

The first building was what they called the shoe factory. That was the first building that we built. That was the first building that some of us stayed in, instead of going back to Kaituma.

It was a challenging task to build a city from scratch, but the pioneers worked day and night to make it happen. They relied on their own ingenuity to make their living conditions tolerable. For light at night, they used handmade kerosene wicks to provide light. They collected rainwater in an old metal drum for bathing. And when they needed to relieve themselves, they simply walked into the bush.

In the summer of 1974, as their utopian dream slowly materialized, the pioneers made arrangements to bring more workers to the settlement. Mike and his uncle, Tim Swinney – a burly, tattooed man with a hearty laugh and sharp wit – took the smaller Temple boat, the Cudjoe, to pick up additional settlers and supplies in Miami. Among the new arrivals were Mike’s wife, Debbie Ijames; his parents, Charlie and Joyce Touchette; and his siblings, Albert and Michelle. Charlie and Joyce Touchette took on the roles of overseeing the construction, and with the larger crew in place, the pioneers made significant progress in their work.

A photograph from 1974 shows just how radical the changes in the settlement were: 40 acres of unobstructed land surrounded by lush tree canopies. The panoramic shot of the rich verdant landscape captures the allure of the jungle, so beautiful in its isolation yet full of foreboding. Four buildings nestle against the outskirts of the jungle, as plumes of smoke from burning windrows rise to the sky.

*****

1974: The First Buildings

Evolution of the Main Building

Before full-scale construction could begin, though, the pioneers needed to sketch a site plan for their property. They discussed the layout of the land, including the size and location of the cottages, the buildings, and all the farms and gardens they hoped to build.

Albert Touchette, Mike’s younger brother, was crucial to Jonestown’s development. He took charge of the fledgling city’s zoning efforts, which included designating land area for specific facilities and purposes. Mike recalls his brother’s strong will and resolute dedication to their community:

I believe in my heart that the majority of that – the credit’s given to Albert. Albert had a knack about him with that place where, ‘we need to do this here, we need to do that there,’ and some of the people would want to argue, and Albert would stand by with what he had to say. That’s how we did it.

Mike still holds his family close to his heart. They were all pioneers – the Touchettes and the Swinneys – and they had poured all their heart and soul into building the Promised Land.

Mike’s Family: The Touchettes and The Swinneys

“I enjoyed it. We had fun. We always had fun,” he recalls working with his family. He lovingly remembers his maternal grandparents, Helen and Cleave Swinney, who played an important role in his upbringing. “I loved my grandparents. They gave me a lot of the values and the beliefs and how I feel about different things. They gave that to me. They helped raise me.”

For Mike, it was never about Jim Jones. It was about his own values. It was his love for his family and the Temple community that spurred him to work from sunrise to sunset. He envisioned a better life for his family, in a place where people from all walks of life could live harmoniously.

Once the pioneers completed their site plan, they – along with their Amerindian laborers – immediately got to work. One of the first buildings they erected was the banana shed, a spacious structure elevated on a wooden platform. Its open framework was made of tree poles, with side panels constructed from troolie thatch. Amerindian tribes traditionally used the troolie palm, with its large rigid leaves and its water-resistant qualities, to build their own homes. The pioneers adopted this practice, incorporating troolie palm fronds into their cottages and buildings. In fact, when Mike’s grandparents, Helen and Cleave Swinney, moved to Jonestown, they lived in one of the troolie cottages.

Next to the banana shed stood the main building. Elevated on stilts to minimize the risk of flooding during heavy downpours, it contained the kitchen and dining area and served as a makeshift dormitory for the early settlers. The original showers in Jonestown, akin to a corrugated tin shed, were built on the side of this building.

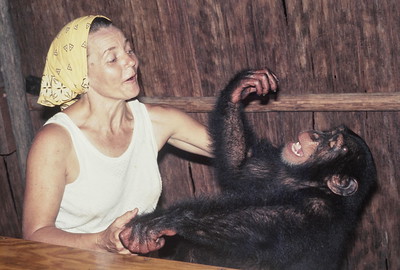

Just a very short distance away from the main building and the banana shed stood a spacious enclosure for a very special resident – Mr. Muggs.

In December 1974, the plane that carried Mr. Muggs, the mischievous chimpanzee cared for by Joyce Touchette and family, landed at Timehri Airport in Guyana. His cage featured two tubs, a swinging rope, and a small enclosure in the upper-right corner. Then-U.S. Ambassador to Guyana Max Krebs, who visited the settlement about a year after Jonestown was established, described Mr. Muggs’ house as a “comparatively sumptuous roofed cage.”

Mr. Muggs’ cage, before and after it was refurbished with a new roof and wooden slats. Credit: MS-3791_00197, California Historical Society Collection in Stanford; The San Diego State University Library, Special Collections and University Archives

Like most structures in Jonestown, Mr. Muggs’ cage was built almost entirely out of tree poles. The original roof was made with thin corrugated metal sheets that extended to the sides, likely in a bid to protect the enclosure from torrential rains. Later on, the cage received a much-needed upgrade: a pitched roof with thicker rafters, along with sturdier wooden slats.

A short distance away was the plant nursery, managed by Greg Frost. This was an important component to the community’s cultivation of crops, which followed on the heels of clearing away the jungle. The farmland eventually provided more than 20 crops to feed Jonestown, and its orchards of citrus and coffee trees testify to the Temple’s long-range plans. But Greg started small, growing avocadoes, papayas, and mangoes, from seed.

As former Temple member Don Beck wrote about Greg Frost:

[He] was fascinated with growing mangoes. He read about techniques to jumpstart their growth. People saved seeds from any citrus or papaya we ate, to start seedlings. Greg had jars and bottles of them growing.

*****

1975-1976: Electricity and Generators

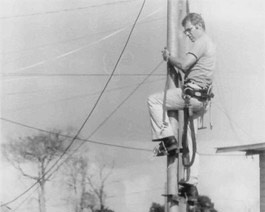

Tom Grubbs working on electrical wiring for the shortwave antenna. Photos courtesy of The Jonestown Institute.

The next step was the acquisition of generators to power the entire settlement, equipment procured by Charlie Touchette and engineered by Tom Grubbs.

Norman Ijames, Mike’s brother-in-law, negotiated a contract with a British firm to purchase two generators – a 300 kW unit and a 100 kW unit – along with a boiler, its feed system, and spare parts. The total cost, not including shipping fees and supervision, amounted to $55,000. It is unclear whether the negotiations for this specific contract fell through, but by the mid-’70s, the pioneers had acquired two fully functioning generators, albeit smaller in size.

Stephan remembers the process of generating electricity in the middle of the wilderness:

“It was poles and lines. Generators, and lines coming from those generators, poles and lines on transformers. After everybody was down there, the two main guys that worked the poles were Chris Rozynko and Chuck Kirkendall. They would climb up and do whatever work was necessary. But power was run, similarly, to how power was run through a town in the States.”

The interior of the generator housing can be seen in one of Jonestown’s promotional videos. In one recording, the camera slowly pans to the left, revealing the wooden poles and corrugated metal panels that enclose the building. An electrical control panel is mounted on the wall, directly behind a large metal drum that stores oil for the power plant. The camera then focuses on a large noisy machine – a 38 kW generator unit – buzzing with jarring electrical sounds.

The man filming the video – either Charlie Touchette or Mike Prokes – explains why they need two energy sources:

For economic reasons, right there behind the oil drum, you’ll see a smaller generator. That’s the one we ran at night. When we shut down the workshop and we do not need all of the electricity required to run the workshop and the clothes dryer, we switch over to the smaller generator, thereby saving on our fuel consumption.

Generator Housing

In the event a unit or two broke down, Jonestown had a secondary power system to avoid prolonged blackouts. “We had multiple generators – it just wasn’t one or two. We had backups as well,” Stephan recalls.

A note from a resident named Lisa underscored the importance of always having functioning generators:

It is essential for our survival that we have a good water supply. I don’t like our complete dependence on generators. Parts or fuel may not be available one of these days. For that reason I feel that we should shift to the use of windmills, which would pump water directly into storage tanks without the use of generators.

*****

Water Wells and Explosive Tanks

After the pioneers installed electricity, the next step was to dig wells to provide water for the community. It was a difficult, time-consuming job. First, Mike operated the backhoe to scoop out soil from the ground, “as far as the backhoe could reach.” Afterwards, the workers dug by hand. The hand digging often resulted in messy, albeit hilarious, incidents.

“The first well that we dug, Davis Solomon and another guy were in the well, and they were digging, and it collapsed on ’em,” Mike recalls with a laugh.

“I think what Mike is laughing at is you do all that digging – it didn’t fall on them, but it all fell in around them – ” Stephan begins diplomatically.

“All that work for nothing!” Mike adds.

“Disheartening at best,” Stephan agrees.

After they successfully excavated their first well, the pioneers sent a water sample to Georgetown for testing. “It came back okay,” Mike says. “So that’s all we did. We just had it tested, and that was it.”

Stephan trusted the earth’s ability to filter its own water. “Water is pretty effectively filtered when it has to run through the earth, and it’s not like pesticides or anything like that were being used down there, which is what can greatly – or animal manure or that kind of thing – we didn’t have any of that around our wells, and that is what can really taint well water.”

And as far as Mike remembered, no one in Jonestown ever fell ill from its drinking water.

After Jonestown had generators, wells, and clean water, the pioneers needed to connect all the components together. It was perhaps the most challenging step of the whole process.

“We had to have generators to do it,” Mike says. “They pumped them into tanks to pressurize it, to get it up to wherever the water was going like to the kitchen or the laundry. To tell you a funny story, if you know anything about pressure, you know your hot-water heater has to be round, so it can take pressure. A square tank with square corners or angles cannot take pressure. Well, one day, a bunch of us – Charlie, Tim Swinney, Jim Bogue – decided one day to pump water into a square tank and pressurize it to get it to the building, to see how it was going to work. And when they did that, the tank blew apart. It sounded like a bomb went off! It knocked Charlie several feet back, it knocked Tim on his butt, Jim Bogue, it all knocked them down. And then Jack Barron, who was the genius of the bunch came out and said, ‘well you can’t do that.’ I think we’d all figured it out by then, we couldn’t pressurize square tanks.”

With 40 settlers now living on-site, Jonestown had come a long way from its meager beginnings as a footpath. 100 acres of land had been cleared and planted with cassava, a staple in Guyanese households. The pioneers had electricity and their own water supply. The farms grew enough bananas, so much so that the settlers sold them to Guyanese soldiers, leaving the spoils for their pigs. The chickenry, which was supervised by Anthony Simon, expanded into several buildings.

*****

The Little Pioneers

In the summer of 1976, Tom Grubbs, a schoolteacher, returned to Guyana with Don Beck to establish an educational program for children. A few young faces can be seen in publicity materials from the early years: Ronnie Beikman, son of pioneers Chuck and Rebecca Beikman; Tommy Kice, son of Wanda Johnson and Tom Kice Sr.; Darren Swinney, son of Wanda and Tim Swinney; Thomas Bogue, son of Jim and Edith Bogue; John Victor Stoen, son of Grace Stoen – and whose conflicting paternity claims led directly to Jonestown’s demise – and Vincent Lopez Jr., a young teenager under the guardianship of Grace and her partner, Walter “Smitty” Jones.

The children appeared in several promotional films for Jonestown recorded in the mid-’70s. In one, the children sit in a schoolroom with Tom Grubbs, studying math equations and writing their answers on a chalk board. In another, they huddle together to examine plants in the field. In a different segment of the video, the children, accompanied by Jim Jones and several adults, walk along a narrow pathway in the jungle that leads to a small creek. One of the children swings on a vine as rays of light pierce through the thick canopy of the rainforest.

The children also harvested sweet potatoes in the fields and tended the garden. They were often in the company of David George, a Guyanese boy adopted by Joyce and Charlie Touchette. Two of the children later took on leadership roles: Kevan Grubbs, then a teenager, oversaw the banana crops, while David George managed the piggery. They all acquired hands-on skills beyond anything taught in a traditional American classroom.

As Stephan recalls, “The kids that were there early had a great support network. Tom Grubbs – well, all of us – we looked out for them. We looked out for the younger people. It was not a fearful environment, which is what it became when my father was there, at least in my opinion. Early on, kids were really looked after and watched out for, so they weren’t thrust into anything that would have been hugely frightening for them. They were introduced to it in a way that was thoughtful and sensible.”

Jim Jones often claimed that the people sent to Jonestown in its early years – both children and young adults – were in danger of being sent to jail if not for his intervention. Mike takes exception to that: “In the early years, they would send down people who were supposedly problems – Paul McCann, Ronnie Dennis, some of the other people who were supposed to be really problem people – and they turned out to be the most lovable, hardworking people that we had.”

*****

Lumber

The arrival of new residents necessitated the construction of additional cottages and facilities, and the demand for lumber increased. The pioneers harvested their own wood, but it was not enough to meet the commune’s growing needs. Left without options, the pioneers were forced to procure lumber from outside sources.

“That’s the reason why the basketball court existed, because we had run out of wood,” Mike explains. “And they had sent the other boat – the Albatross – to Venezuela to try to get some wood.”

The Basketball Court

“That was the floor of a building that never was,” Stephen adds. “Dad was pinching pennies, so he might not have wanted to pay for the wood. We did go upriver a couple of times to get lumber, and eventually we did put in what was an Alaskan sawmill. The sawmill had table saws, which we used to cut timber into boards. But most of the wood we needed, we could not have gotten from around us and from the people that we had, so we had to go upriver to get it.”

The Saw Mill

In one of Jonestown’s publicity videos, Jim Jones appears in an open field before a stand of leafless trees. “They are dying,” he says, “but we’re purposely allowing that. This is marketable lumber, very expensive lumber. The trees back with foliage, of course, that is the way all vegetation looks here – rich – but we’re letting this happen purposely, so we can cut them down for our sawmill, process them for housing for you. And then later, to sell to make a living for us.”

Unfortunately, this approach was not sustainable, and Jonestown continued to face difficulties harvesting wood.

*****

1977: Stephan Jones Moves to Jonestown

Stephan Jones was one of Jonestown’s pioneers who worked long, hard hours on its construction, but he never intended to live there.

“I had left the Temple and had an apartment of my own,” he says. “My mother had gotten it for me. Dad came to me and wanted me to move back into the Temple, but I refused. So his strategy became to ask me to make one more trip, which I also refused to do. And then he talked to my mother and promised her that he wouldn’t keep me down there, so I agreed to go. But once he got me down there, he said, ‘You’re not coming back.'”

Despite being the son of the Temple’s leader, then, Stephan had no say in his own future. That was February 1977.

“When we were in Guyana at that time, it was virgin bush,” Stephan recalls, his voice tinged with remembered awe. ” Just a story to give you an idea of how thick it was: Gene Chaikin one time had gotten separated from a group of us. We were in a clearing and he was not ten feet away from us, and he was hollering for us, because he couldn’t see us. We couldn’t see him either. Eventually we learned from the Amerindians – a man named Jupiter, in particular – how to move through that bush. I’m 6 foot 4, and he was 5 foot 4, but he moved a lot quicker and more lively than I did. We eventually learned how to kind of find our way through, and where the openings were and the paths were. But that jungle was astounding. It was magnificent.”

Mike agrees. “You could be in a clearing and all the trees are gone and all that. You could walk inside a bush – it literally looked like a wall – and you could walk a few feet in, turn 360 degrees, and you have no clue where you were. That’s how thick it was.”

For a young man like Stephan whose choices had been made for him, it must have felt freeing to disappear in the dense thicket of the jungle. In fact, it wasn’t too long before he fell in love with his new home. It was similar to his experiences as a child, when he escaped his father’s attempts at control by running deep into the woods, finding solace in the wilderness.

My experience with my father and what I saw behind-the-scenes and behind-the-curtain – just how outraged I was by it, frankly – getting down there with a group of people who had a mission and were focused on that mission, working hard side-by-side with people that I loved, and building a town essentially for the only community I had ever known, was hugely meaningful to me. I was thrilled to be there with the people that were there.

*****

Welcome to the Team

After moving to Jonestown, one of Stephan’s first tasks was to dig wells. His recollections remind him of a story of a water well, a possum, and Tim Swinney:

We were digging a well near town. I was pretty new to the team at that point, and we left it overnight. When we came back, there was a possum in there. Now I don’t know if you know about possums, but they’re pretty gnarly creatures when they’re cornered – they got some big ol’ teeth in their mouth! We’re all looking down at that thing in there with Tim Swinney, who was a big burly guy that you did not want to get on the wrong side of. And we’re looking down there, and I said, ‘Man. Well, what are we going to do?’

He said, ‘We’re going to have to go down there and get it.’

And I said, ‘Who’s going to go down there?’

And then Tim threw a bag into the well. And I said, ‘Well, who’s going to go down there and get that?’

And he reaches over, and with one finger, gives me a push and says, ‘You are.’

Next thing I know I’m getting in the well with a possum and a bag! But I managed to get it out of there.

*****

Housing

Like the pioneers before him, Stephan learned a multitude of skills. When he was not dodging possums in a well or laying fire to the bush, he built cottages with his friend, Albert Touchette, and the other young men in Albert’s construction crew. When Thomas Kice Sr. relocated to Jonestown, he became the Wood Shop’s Master Carpenter and took charge of building the houses.

Building houses by hand was not an easy task, but the residents had become good at it. First, felled trees were sent to the sawmill where a crew that included young men like Paul McCann and Al Simon – and young-at-heart men like Jack Beam – cut the trunks into lumber by hand.

The lumber was measured and cut with a saw before being assembled into floor joists, supported by sturdy posts on the ground. The structural supports of the cottage were assembled on-site, while the walls were prefabricated by a different crew. Later, the men installed slanted roofs made of corrugated metal, measured to extend beyond the walls to provide shade from the sun and protection from the rain.

Housing Construction in Jonestown

Stephan recalls what it was like building a cottage in the jungle, which had unpredictable weather: “Digging postholes, for example, for the cottages out in the open field – you wanted that rain to come. Sometimes when the rain came, it came like a wall. I mean, you could see it coming, and I would just stand there and put my arms wide open and let it hit me ’cause it was so hot down there.”

Most of the houses in Jonestown were simple structures built with wood paneling. A few were constructed using troolie palm leaves, which were harvested, trimmed, and woven into panels to form the walls of a cottage. The settlers also used the fronds, which could measure up to 30 feet long, for thatching roofs.

The troolie cottages were located near a small cluster of medical offices, away from the overpopulated cottage complex. The kitchen, dining area, and shower building were also nearby. The troolie cottages offered its inhabitants more privacy and convenience than the average resident, who lived in overcrowded cabins.

Troolie Palm Fronds in Construction

Five large buildings, called dormitories, housed 30 to 50 people each. Three dormitories were designated for seniors, one for toddlers and infants, and one for young adults, such as teenagers assigned to the Learning Crew. A shower building stood between two dormitories, a welcomed convenience for the residents.

Jim Jones had two living quarters, the earlier one was called the East House, which was located past the cottage complex and dormitories. A photograph identified as the East House shows a small wooden bungalow with a porch, surrounded by bright flowers and tropical plants.

As Stephan recalls, “His first cabin was built around the same time that other cottages were being built. We were building what we called the dormitories, which were big buildings nearest to the pavilion. Mom’s cottage, or what became her cottage – I don’t think it was made for her – but there were a number of cottages that were made on the other side of the main road from the pavilion, alongside the kitchen area, the dining area, and where they later put the infirmary.”

As Jim Jones’ increasing paranoia began to consume him, he ordered Stephan and the construction crew to erect a new house on the other side of Jonestown. This house, known as the West House, had two bedrooms and a porch. It was built in a private area beyond Mr. Muggs’ cage and the troolie cottages.

“Dad, for some reason – you know, concerned about threat, paranoia, or just to create drama that there was a threat when there wasn’t – he wanted another place built on the other side of town, and that happened when everything else was built, or close to it anyway.”

*****

Outhouses

The outhouses were built around the time of the mass exodus, when hundreds of people arrived in Jonestown en masse during the span of a few months in 1977, overwhelming the settlement and strained its resources.

This is how, Stephan explains, they built an outhouse: “Dug a big hole and put a building over it.” And that is exactly what the pioneers did. The communal toilets were built over a deep pit, which measured 15 feet from top to bottom.

The outhouse was divided into two rooms: one for men and one for women. Each room had a bench with six oval-shaped holes that served as makeshift toilets. With hundreds of new residents now living in Jonestown, the latrines were built with simplicity and efficiency in mind.

The differentiation between men’s and women’s facilities didn’t always apply. “Sometimes women sit next to men. Unfortunately, the women’s lines are always longer than the men’s lines, and when somebody could not wait – and there are times when you couldn’t wait – the women would come in and sit right down next to you and do their thing.”

As for the waste, it remained in the hole. The stench and flies discouraged residents from lingering in the area. There was little concern about human excrement seeping into the water system, as the soil’s tough composition prevented that.

“When you got down to about four or six inches of top soil, the rest of it was hard, hard clay,” Mike explains. “And even though we didn’t experience it at the short time that we were down there, it would have to be a big deal for any waste to get into the water system just because of the clay.”

*****

The Temple Boats

As Mike notes, “There are only one or two ways of going into Jonestown. You either take a 24-hour boat ride, or you take an hour-and-some-odd-minute plane ride. When we were down there, the only way Port Kaituma got food was from the government boat. The government boat would bring up supplies and all that stuff, but that boat would break down.”

Throughout its brief history, Jonestown relied almost entirely on imports of supplies, and did not want to complicate its efforts to sustain itself with unreliable transportation. Since its primary access to the outside world was down the Kaituma River, the Temple leased two boats, the Albatross and the Cudjoe, for the community’s supply runs. The pioneers also used the Cudjoe, to help local Guyanese people.

That was consistent with the how the pioneers and – later – the larger population of Jonestown interacted with their neighbors. Despite their own hardships, they did their best to help the local community. They distributed bags of rice in Port Kaituma and provided medical services as best as they could.

“We would use the Cudjoe to bring up food supplies and whatever else was needed to the community,” Mike adds. “The other thing is, at one time, we employed more than 200 Guyanese people on building the project. Most of them were farmers that would help plant the crops and all that stuff, and we also provided medical assistance, as best we could.”

The size and nature of the cargo could prove to be quite dangerous, especially when the pioneers unloaded gasoline drums, stacks of lumber, sacks of food, and heavy equipment from the two boats.

When Jim Jones and Mike Prokes visited Jonestown in 1975, the pioneers recorded audio letters for their loved ones back home. In a tape recording of that meeting, Albert Touchette described the near-fatal accident that occurred when the crew unloaded 27 drums of gasoline from the boat:

On the second to the last barrel, Tim [Swinney] looked at his rope, and it had frayed. It was cut, and there were only two strands holding the whole rope, and he said it’s good for at least two more barrels. The barrel was almost set down on the dock, and just as it got three or four inches from the dock to rest on it, the rope snapped. We were picking the barrel up with a set of barrel hooks, which is a metal chain and metal hooks, and these flew off of the barrel and they missed Davis Solomon’s head by just inches.

Years later, Stephan, Albert, and other young men became part of the dedicated crew that routinely unloaded supplies from the boat. They would form a human chain and throw heavy bags at each other until the early hours of the morning.

As Stephan recalls: “The joke was you were trying to get the guy before he turned his back to you. You were trying to go fast enough that you caught the guy in front of you in the back? It’s a big game, because if you’re not moving fast enough, you’re going to catch a bag of flour in your lats. We made a sport out of it. And on top of that, we did incredibly hard work, quickly and efficiently.”

“Those sacks of flour, beans, rice, and sugar – those things are heavy, they were like a hundred pounds or so,” Mike remembers.

“The sugar was two hundred pounds,” Stephan says. “But when we got done we’d be walking dough boys – we had flour, and sugar, and rice, just caked to our bodies. We’d drape ourselves over that last tractor load, we’d get back, we’d walk into the shower which was just a pipe sticking down from the ceiling. It was only cold water. We would gladly walk under that cold water! With my clothes on.

“I would get them completely drenched, get ’em cleaned that way, so I rarely had to use the laundry. I would clean my clothes on my body and then strip as I was showering until I cleaned my body. Pick it up, wring it out, and go to my cottage.”

Mike recalls a similar experience: “I got used to that the first couple of years, because we had no laundry. What we did, we would stand out in the rain and actually, before we had the showers, we’d sit there and started cleaning our clothes off. Put ’em on the next day and go to work.”

By the time the crew unloaded the last bag of supplies from the boat, the sun was shining on them.

*****

Brotherhood

Jonestown Pioneers

Stephan likes his solitude.

I used to go into the bush when it was still dark, really dark inside, and I would make myself a part of it and watch it come alive. You’d be amazed what I would see in there because the animals wouldn’t know I was there. The only thing you would think exists were birds and monkeys, ’cause everything else would just get the heck out of there. They’d know you were coming long before you got there. But when I could make myself a part of it, it was really magnificent.

Losing himself in the vast wilderness must have brought him a sense of peace, especially when he found himself so deep in the thicket that he could no longer hear his father’s voice on the loudspeakers.

At long last, he could escape him.

Stephan admits that during his childhood, his father’s tight control resulted in difficulty for him to form friendships. That changed when he arrived in Guyana, where he finally found the camaraderie and brotherhood that had eluded him for most of his life.

In Jonestown’s happier, earlier days, when the settlers “ate like kings,” Stephan awakened every morning with an eagerness to begin a day of arduous yet satisfying work.

“The way I remember it is we didn’t have any alarm clocks,” Mike explains. “We just woke up with the sun, got dressed, ate, and went to work. It was that simple. Come rain or shine, we worked. There was a lot of days down there where it rained and rained and rained. We’d come back at night, wring our clothes out, hang ’em up, and put them back on the next day.”

“We did a lot of different things,” Stephan adds. “I worked in the bush, where I would bring down trees. I would work on crews that dropped large areas of bush that would sit for six months. Then we would go through two-men teams – one guy with a torch, one guy with kerosene – and just burn as we were running through, laying down the fire. Sometimes when the boat came in with supplies we’d have to work all night and then get up and work the next day. And of course I remember Charlie Touchette going around in the morning sometimes, tapping on the door, smacking on the door, if we had a late night working.”

Before the mass exodus to Jonestown took place, Stephan and Mike enjoyed the freedom they experienced in the jungle, when work was tough but purposeful, and food was abundant.

“When we got off, we ate really well and did what we wanted to do,” Stephan explains. “Sometimes we’d only get six hours of sleep, but there was a freedom in that. We were working together, we loved each other, we loved what we were doing, we loved who were doing it for.”

At the time, there were about 60 people living in Jonestown. Jim Jones and his leadership group were not yet a permanent fixture in the settlement, which allowed the young men to foster genuine friendships with each other. They wrestled, played cards, or gathered around a big screen and watched a film. Stephan fondly recalls one such evening:

“One night, when we got off work, they were going to have a movie night. They had a big screen pulled up, and the movie we were watching was Dirty Harry–” He pauses as Mike laughs. “If you know the Temple, you know Dirty Harry was taboo, right? There’s no way it would have been okay with my dad to watch Dirty Harry. And not only were we watching Dirty Harry, some of these guys would watch it so many times they were reciting the dialogue.”

Stephan and Mike hold the memories of their fallen friends and families close to their hearts. Albert Touchette, Ronnie Dennis, Vincent Lopez, Emmett Griffith – they all come to life when Stephan and Mike talk about them and the brotherhood they shared.

“A bunch of us – Mike and I, his brother Albert, Emmett Griffith, Ronnie Dennis, Vincent Lopez, and Mark Cordell – would all sit on our little stoop, and our stoop looked right at the main path so people would just have to go by. We would talk about people as they walked by, something along the lines of, ‘He’s cool,’ or ‘She’s cool,’ or ‘Boy, there goes Miss Goody-Two-Shoes.'”

There was no catcalling from the young men, or carousing with girls in Port Kaituma, as some detractors have alleged. That’s something that Stephan is proud of.

“One thing we would never do – and this is something I feel good about, and it’s one of the many values that I took away from my Temple experience that’s very meaningful to me – we would never think of objectifying a woman to each other. Women were to be revered and respected–”

“And not only that,” Mike adds, “they weren’t going to walk out there and then walk back. All we had was a couple of tractors. We had a jeep and a pick-up truck. They couldn’t have gone in there to do that. I don’t see how it could have happened.”

The pioneers and their friends mostly stayed in Jonestown, a place as remote as any could be. With their limited mode of transportation, it was difficult for anyone to leave the settlement and carouse in Port Kaituma. If residents thought about leaving Jonestown on foot, it was going to be a taxing challenge.

“It’s a long walk,” Stephan says. It reminds him of an experience that terrified a few of the settlers who had walked the road to Jonestown:

Right after you get into our road, we had banana trees on both sides and the bats would fly back and forth constantly between the bananas. So if you walk that gauntlet, you had bats just flying all around your head the whole way. Now that didn’t bother me – I thought it was incredible – but it freaked some guys out, understandably.

So the young men stayed in Jonestown and made it their own world.

“Many of us became men down there,” Stephan reflects.

Mike, who spent his early twenties in the jungle, agrees. “That’s right, you really didn’t have a choice.”

“Not just emotionally but physically,” Stephan continues. “When Albert came down there, he ended up looking like a body builder. Towards the end, it changed, because our diet changed once Dad was down there. Ronnie Dennis is an example. Ronnie was just this skinny, scrawny little kid, and he ended up looking like a gymnast. So not only transformed emotionally, but physically. And you know, as young men, you feel good about that.”

When Jim Jones ordered the mass exodus to Jonestown, everything changed. Dirty Harry was replaced by Soviet propaganda films, and the camaraderie and brotherhood the early settlers experienced was replaced by paranoia and fear. As the populace grew, housing facilities overflowed with residents, and resources were stretched to their limits.

“I’ve said this before to other folks,” Stephan says, “but when Dad got down there, we worked fewer hours, but when you got off, your time was his time. He tried to control everything you did at all times, and work largely went from a means of production to a means of control. Once he got down there, everything about it changed for me. It was vastly different when Dad was there.”

“It wasn’t fun like it was in the beginning,” Mike agrees emphatically.

“Yeah, incredibly oppressive. Oppressive would be the word for me,” Stephan adds.

“To this day, I feel very, very lucky that my job was to run a bulldozer,” Mike admits. “I tried to put behind every excuse to put lights on the machine, where I could work at night rather than plowing the fields or working on the road, just to avoid having to go into some of those meetings. Hell, those meetings went on til what, 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning sometimes? Sometimes all night. So with my job I didn’t have to worry about as much as what Stephan and everybody else did.”

The brotherhood the early settlers shared was strengthened by the increasingly oppressive environment they lived in. Stephan still thinks of his old friends as his “safe people” – the kind who would know where to find you if you disappeared into the dense jungle foliage, or would grudgingly lower themselves into a pit of human waste to retrieve a pair of false teeth, and who would subject you to a never-ending barrage of Dirty Harry one-liners – all part of building their shared vision of the Promised Land.

Quietly, Stephan reminisces about his friends and his days living in Jonestown:

We did a lot of different things together. Sitting on a stoop talking about folks, hanging out. Incredible camaraderie. And I think that’s one thing that comes from living in an oppressive environment – you find your community, you find your safety, you find your safe people. I feel blessed that I had that before Dad got down there, because I really formed these wonderful relationships.

It is heartbreaking to note that Jonestown’s tragic end has overshadowed the vibrant memories of the men, women, and children who built and lived in Jonestown.

Despite the infamy Jonestown is often remembered for, the legacy of the pioneers cannot be forgotten: their camaraderie and resilience in their shared pursuit of a utopia free from hate and injustice.

Sources:

The Jonestown Institute

- Anthony and the Jonestown Chicks, Don Beck

- A Peoples Temple Life, by Don Beck.

- Snapshots from a Jonestown Life, by Phil Blakey

- Ruth’s Teeth by Stephan Jones

- Mike Touchette Interview with Katherine Klapperich.

- A Place Like No Other: Jonestown’s Early Years, by Mike Touchette

- Construction, Power, and Transportation Department

- Housing in Jonestown

- Map of Jonestown

Audio Recordings from The Jonestown Institute:

- Albert Touchette, Q570 Tape: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27467

- Norman Ijames and Generators, Q674 Tape: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28235

The Peoples Temple Flickr site

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/50010214703/in/album-72157714726377762/

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/50011005677/in/album-72157714726377762

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/50011005602/in/album-72157714726377762

- Bernie Matthews with Archie Ijames: https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/50011006162/in/album-72157714726377762

- 1976-1978 Construction in Jonestown: https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/albums/72157625011868273/with/49694941197

- Children and Adults Sorting Beans, Peoples Temple Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/50014368856/in/album-72157714726377762

- Aerial view of Jonestown in 1974, Showing the First Buildings and 40 Acres Cleared: https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/49835518731/in/photolist-2jcC415-2iVN4tz

- Banana Shed and Main Building in 1974: https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/49835824172/in/photolist-2iW9QRz-8eYXL9-2iW8hra-2iW5w1N-2iW8hL8-2hFcRC2-2hFcZWg-2jnzp5K-2iDXWKk-2iW5wpU-2iDZnSy-2iDGmoe-9oMoTm-2hYFE6p-2iVKkdt-2iVPCgN-2iVNUBq-2iVN4tz-2iDEjwj-2jnAwAj-2iVGT4i

- Muggs’ Cage: https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/49835684022/in/photolist-2iDZnHk-2iVMKv5-2iVJcgD-2iVGT4i-2iVNUBq-2iVNsXe-8dwpmf-2iWqyVF-2iHmDJs-2iVNuDW-2jcC41W-8ddmDX-2iVK1Zz-2iVMKud-2iVLTTK-2iVKVnt-2iVMv7B-2iVJQDe-2iVJBCz-2hFcRC2-2oP9JqC-2ikt5F7-2iDVrET-2iDXWhM-2iFyL7a-2hFcRuM-2iDGmoe-2hFfyvi-2iDEjwj-2hFfy7c-2jcAH23-9oMoTm-2iVN4tz-9oMnDf-8dWRbB

- Muggs’ Cage, New Roof and Side Slats: https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/49834846453/in/photolist-2iDZnHk-2iVMKv5-2iVJcgD-2iVGT4i-2iVNUBq-2iVNsXe-8dwpmf-2iWqyVF-2iHmDJs-2iVNuDW-2jcC41W-8ddmDX-2iVK1Zz-2iVMKud-2iVLTTK-2iVKVnt-2iVMv7B-2iVJQDe-2iVJBCz-2hFcRC2-2oP9JqC-2ikt5F7-2iDVrET-2iDXWhM-2iFyL7a-2hFcRuM-2iDGmoe-2hFfyvi-2iDEjwj-2hFfy7c-2jcAH23-9oMoTm-2iVN4tz-9oMnDf-8dWRbB

The Jones Family Memorabilia Collection, San Diego State University:

- Road to Jonestown, 1974: https://digitalcollections.sdsu.edu/do/3fd69954-c7d7-42a3-93b4-13471bcffc55

- Children Sorting Sweet Potatoes, SDSU: https://digitalcollections.sdsu.edu/do/e0760b6a-182b-44e1-9fd1-33a3e4c6b6c8

- Children Gardening, SDSU: https://digitalcollections.sdsu.edu/do/2ee28638-1d89-4e9e-acc3-1f4d116df508

- Photograph identified as that of the East House: https://digitalcollections.sdsu.edu/do/e39c66b0-f8ce-416d-9e96-f240996a7e74

Books:

- Guinn, Jeff. The Road to Jonestown. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

- Hall, John R.Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick: Transaction Books,

- Reiterman, Tim with John Jacobs. Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People. New York: Dutton, 1982.

Films Archived by Transmissions from Jonestown:

- Generator Housing, Jonestown Promotional Film

- Jim Jones and Leafless Trees, Jonestown Promotional Film

- School Children in Jonestown, Tom Grubbs Quizzing Children, Jonestown Promotional Film

The Internet Archive

- Tom Grubbs Quizzing Children in Jonestown: https://archive.org/details/chi_000117

(Danielle Redifer became interested in the early years of Jonestown and the people who built it. She maintains an account on the Jonestown Pioneers on Instagram that documents the work of the pioneers, and honors the victims of the tragedy: https://www.instagram.com/thejonestownpioneers/. She is also the author of The Touchettes in Indianapolis: A Life Before the Temple. She lives in Alabama with her husband.)