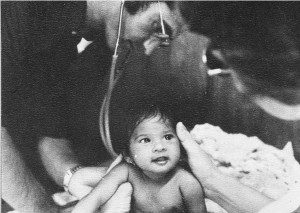

Photo source: Jonestown brochure

(The following is an excerpt from the first chapter of a book-in-progress, And No One in this Town Burns Bright Enough, by Sherrie Tatum. Some scenes in this chapter were included in Sherrie Tatum’s Remembrance of Larry Schacht, from last year’s edition of the jonestown report. Her other article in this year’s edition of the jonestown report is “Your dear voice . . .” She may be reached at sherreleven@yahoo.com.)

Larry is with a group of shadowy figures at the foot of the massive marble steps. We are outside of a sort of temple, and I am with my dad and my sisters and brothers. In the dream I am young, and when Larry sees me, I glance down, feeling the old familiar shyness. But his gaze is steady and keen, with an intensity I had forgotten. That is what makes it all so real, the way he used to look at me, that look that contained so much, a teasing sense that he could see through the shyness, a sense of promise. Just the look, and he is gone … I don’t want to wake up … I’ve waited so long.

It is Christmas time, a time when the veil is thin between our world and theirs, a time when dreams become visitations. Larry has been dead for 31 years …

It is the dead,

Not the living, who make the longest demands:

We die for ever …

Others have often visited in dreams, but why is Larry here? Larry, who I’ve barely thought of for so long? In fact, I spent many years suppressing my memories of him. Did I try to forget out of a sense of horror at what had happened in a remote jungle 31 years ago? Or was I not able to face the sorrow and regret for mistakes made by a confused girl more than 40 years ago? Perhaps nothing could have been changed. Perhaps fate had already set Larry’s footsteps on a path that my feeble power could never have diverted. Maybe I never allowed my memory to dwell on this time merely out of a reluctance to make too much of a relationship that floated in and out of my life for five years, then was gone.

Why does Larry haunt my dreams after all these years? As I slowly wake I notice the printed pages next to my pillow. Pages that contain the jumbled thoughts I started typing up after watching the documentary.

As I watch, I eagerly scan the multitude of faces, sure that I will recognize even after so long, that wide forehead above intense dark eyes gleaming with intelligence. Most of the old footage is grainy, with washed-out colors. The people in the congregation seem to be moving in slow motion as they sway to the music and look up adoringly at the dark-sideburned preacher. He is wearing a suit with the wide lapels and wide tie fashionable at that time. To me he looks too slick in his cheap suit, too much like, well, a preacher. In one short clip he gestures toward himself and says with false modesty, “Many people say they can see God in me.” I cannot imagine Larry, the sharp and insightful boy I once knew, being taken in by this man. I cannot imagine him joining in the revival-style emotion displayed by the mostly black congregation. Still I search, but the camera moves too quickly over the crowd, and I do not spot him. When the preacher speaks again, he sounds like an old-style Bible-thumper, but his words are of those of a revolutionary: “I represent divine principle, total equality, a society where people own all things in common, where there is no rich or poor, no races.” His voice rises to a shout, “Wherever people are struggling for justice and righteousness, there I am.” The few white members of the congregation look like me at that time, idealistic Children of the Revolution, searching for a better way to live. The preacher seems to offer a life of purpose and a chance to be a part of something bigger than themselves. Interspersed with the vintage footage of the congregation in San Francisco are tight close-ups of the present-day faces of Deborah Layton, Grace Stoen, Stanley Clayton, and others, as they talk about the early years of Peoples Temple and the idealism and brotherhood that bound them to “the cause.”

As the documentary draws to a close, I feel disappointed that there was no mention of my friend, but also somehow relieved. Just seeing the film has reawakened a sense of tenderness and protectiveness of his memory, and I’m glad that his role in the tragedy is not mentioned. That night I feel overwhelmed by sadness. Sadness that so many died. That he died. Years of unshed tears for someone so blessed, yet so flawed. The elegiac lyrics of a Richard Thompson song fill my mind, “And there is no rest for the ones God Blessed / And He blessed you best of all…” Years of remorse for all the feelings that went unspoken … I feel compelled by a desire to go back and reclaim what was lost … sadness and regret for something unfinished …

In the days after watching the documentary, I find myself obsessed day and night by insistent but half-remembered feelings. As I drive to work I think of the time long ago when Larry and I were drifting in and out of each other’s lives. Again regret, sometimes so strong and unbearable that it pushes memories aside. When was the first time I ever saw Larry? The feelings are there but no details. I slow down on the narrow back lanes of Tarrytown and reach for the remote that opens the heavy iron gates. I park on the other side of the low stone wall and walk into the dark, story-book mansion where I care for the pale, motherless children of Austin aristocracy. They are still sleeping when I arrive, so I have some time to myself in the kitchen. I turn on the radio and listen to John Aielli while I have a cup of tea and look over my day-planner. The quiet opening words of a song from long ago barely enter my consciousness and even when I hear “Love is the o – pen – ing door / Love is what we came here for / . . .” I do not recognize that it is Elton John, just that it is a song that Larry would have known. Again the regret … for what was never said … “Love is the o – pen – ing door / Love is what we came here for . . .” In the silent old house full of the memories of generations, I sense a subtle vibrational shift, a response to my longing for connection expressed in a song from a gentler time. “Love is the o – pen – ing door / Love is what we came here for . . .”

I know through sad experience that the bonds of love are stronger than fear, stronger than death. Perhaps the subtle response is that of a lost but gentle soul. Is there still love in this world for one who has been condemned by history? Will his memory be associated always with poison and mass death? A jungle night, the screams of women, the cries of dying children? Photographs that shocked the world: remnants of purple liquid in a metal tub, hundreds of bloated bodies lying face down around the pavilion? Even the many who loved Larry long ago, had perhaps, like me, forgotten this gifted boy after his final actions. Many others who never knew him have judged harshly.

As the song continues I notice a tiny bird in the winter sunshine. It is a reminder that another spirit haunts me – the girl I was in 1965. Although the words are softly sung, there is a persistent urgency in the lyrics that perhaps is better understood as one grows older. I feel that I am hearing the song for the first time, that the simple words express profound meaning and purpose:

May well be simple but they’re true

Until you give your love

There’s nothing more that we can do

Love is the opening door

Love is what we came here for

I have taken the first steps through that opening door – a cool fall night, the intriguing boy who didn’t go to our school, but showed up with his guitar. I also remember the girl who quietly watched, taking in every detail. I feel great tenderness for that shy girl, who did not realize her power. Did not know how great a gift it was to simply bring a boy to his feet and across a room on the pretext of asking for a cigarette.

And so the turbulent beginning, tangled memories and emotions come tumbling out, threatening to overwhelm me. Just getting it all down helps, no matter how vague, the process will eventually bring at least some order to the chaos. As the days following the documentary go by, in addition to long-forgotten emotions, I also begin to feel tremendous curiosity and hunger for information about Larry and his involvement with Peoples Temple. What might have influenced the brilliant and talented 16-year-old boy I first met in 1965, to take up his fatal role in the tragedy 13 years later? This is the question that drives me to find answers. At first I find a few newspaper articles written at the time of the suicides, but there is almost nothing about his life before Jonestown.

Early reports reveal that even the number of dead was a mystery, as reported in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette:

Nov. 22, 1978 Houston (AP) The camp doctor who reportedly brewed and administered the poison that killed more than 400 people in Guyana had written to his family of “the satisfaction of assisting poor people, many of whom have never seen a doctor in their lives.”

In the days following the shocking and sad events in Guyana another subject of interest was the lure of California for young “seekers.” In a New York Times article dated November 29, 1978, entitled “How California Has Become Home for a Plethora of Cults,” John M. Crewson wrote: “[O]ne of those seekers was Larry Schacht, a young Texan who, in the turbulent summer of 1969, packed a few belongings and left behind his troubles in school to join the tens of thousands of other young people who were moving westward.”

Coming across this information brings another scene to mind – the very last time I ever saw Larry. But the article has the date wrong. It was May of 1970, the day after the Kent State shootings. By this time I had left Houston and was attending the University of Texas in Austin. Still very involved in student political movements, I was hurrying across the UT Co-op parking lot with a group of friends on our way to a big protest on campus. At first I didn’t see Larry leaning against his car, but just sensed that he was there. He called out to me. In that instant, all the forward momentum of my life, all the good things – leaving the heartaches of Houston, enrolling at U.T., finding a stable relationship – stopped. All the old feelings came back, and my world seemed empty again. Seeing Larry opened up the wounds, the regret, the sense that there was something unfinished between us. Larry too was leaving the heartaches behind – he had stopped briefly in Austin on his way west. I looked in his eyes for that old look, the look that promised that he would be back, that our story was not over. This time his eyes were veiled, looking off in the distance as he told me he was headed for California. We held each other in a parting embrace, but I never imagined that that would be the last time I would ever see him.

As the Crewson article continues it gives me some of the information for which I have been searching:

Lonely and confused, frustrated by the Vietnam War and profoundly unsure of his future, the earnest young man, like so many of his contemporaries, finally came to rest in nearby Berkeley. There, according to his friends he tried drugs, dabbled in meditation and Chinese philosophy, experimented with macrobiotic diets and took an active role in political protests.

I had sometimes wondered what his experience had been in California. A boy so loved, sad to think of him “lonely and confused.” If only things had been different for us … that night he showed up at my door … that last night he came to see me in Houston … The article is wrong about something else too: he had “tried drugs” long before going to California. That was the problem. Those who knew Larry in Houston had been alarmed for quite a while by his growing paranoia and were concerned for the physiological and psychological well-being of this gifted boy. For this reason, I was happy, but quite surprised when I heard sometime later from his brother Danny that Larry was attending medical school in Guadalajara. The article confirms that information: “But it was not until the young man was introduced to Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple that Larry Schacht gained a sense of purpose that had eluded him for years. Encouraged by Jim Jones, he re-enrolled in school and became a doctor.”

However, this statement only opens up more questions. Exactly when and how did he meet up with Jim Jones, and why did he decide to go to medical school? Larry had always been an artist and a musician. As I think about this, another early memory returns of Larry and me in the garage apartment. As he leafs through the pages of Gray’s Anatomy, I can sense his fascination as he shows me some of his favorite illustrations. In using the medical book to make his drawings more accurate, he had become enthralled with the intricate beauty of the underlying bone and muscle structure of the human body. He said that the book had inspired in him an interest in anatomy and he had even considered the possibility of becoming a doctor. He would have been about 18 when he told me this. I remember thinking at the time that he certainly was brilliant enough for medical school and also had the compassion to be a great doctor. This was all before the devastation of his addiction.

I too, had been one of those “seekers” venturing to California in the 1960’s. I guess I exemplified Joan Didion’s observation in Slouching Towards Bethlehem:

San Francisco was where the social hemorrhaging was showing up. San Francisco was where the missing children were gathering and calling themselves “hippies.”… We were seeing the desperate attempt of a handful of pathetically unequipped children to create a community in a social vacuum.

“Social hemorrhaging”? Perhaps. All I know is that at 17 when someone offered me a ride to Berkeley, I didn’t even think about it, I just went. My own sense of community had been fragmented long before by those I trusted., Didion goes on to describe the romanticism that motivated me and many others including Larry to head west:

… It’s a social movement, quintessentially romantic, the kind that recurs in times of real social crisis. The themes are always the same. A return to innocence. The invocation of an earlier authority and control. The mysteries of the blood. An itch for the transcendental, for purification. Right there you’ve got the ways that romanticism historically ends up in trouble, lends itself to authoritarianism. When the direction appears. How long do you think it’ll take for that to happen?

How long did it take for that to happen? Joan Didion wrote these words just a few years before Jim Jones began recruiting “missing children” off the San Francisco streets and turning them into dedicated followers of “the cause,” so dedicated that their sense of self became, as Crewson described it, so completely “entwined with that of his personal savior that when Jim Jones decreed the mass suicide it was, by all accounts, Schacht who mixed the poison that the faithful, himself included, used to end their lives.”

As for my California experience, perhaps it is symbolic that the bass notes of 96 Tears came pounding out of the car radio just as we arrived at the Golden Gate Bridge. I leaned back in my seat and watched the dark beams alternate with the bright sky as Question Mark and the Mysterians sang, “Too many teardrops for one heart to be cryin’ / Too many teardrops for one heart / To carry on . . .,”

I only stayed a few months, never feeling at home in California. Without the built-in social network of school and family, it was hard to get to know anyone. I was mostly approached by older men who offered me various drugs and seemed to sense my aloneness and vulnerability. Not once did anyone look at me and say, “Hey, she’s just a kid, she might be scared and lonely.”

Perhaps Larry’s experience four years later was similar to mine in some ways. The article from 1978 about “seekers” concludes, “Sooner or later, most of them discover that California, with its supermarkets, freeways, giant apartment complexes, shopping centers, huge universities, and other monuments to impersonality, can be one of the loneliest places on earth.”

My California adventure ended when my dad tracked me down and sent me a bus ticket home. Arriving back in Houston a few months into what would have been my senior year, it felt strange to me that most of my friends, including Larry were still in high school.

© 2010 Sherrie Tatum