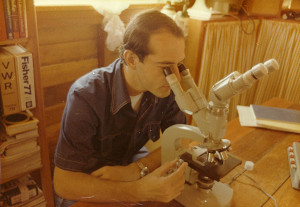

Photo Courtesy of California Historical Society, MSP 3800

(This article evolved out of research for Sherrie Tatum’s book in progress, And No One in this Town Burns Bright Enough, an excerpt of which can be read here. She may be reached at sherreleven@yahoo.com.)

My search for information about my old friend, Larry Schacht began after I saw the PBS documentary, Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple, and led me to the Jonestown Institute website. One resource I discovered was the site’s tape archive, and of course what really drew me in were the notations “Larry Schacht (speaks)” on some of the transcripts.

Initially, I just wanted to hear his voice again. It was a voice I had not heard since May of 1970, the very day he left on the fateful journey that took him to California and eventually to Peoples Temple. I recalled Larry’s voice as one of his most distinguishing features – one of the qualities I found most attractive about him, his absolute conviction and strength expressed in deep and righteous tones. He always sounded so certain of everything, sure that he was right, that he spoke the truth. As a young girl I found this very reassuring. Others must have felt the same, since Larry was quite often the central focus of the loosely-knit group of budding young political, artistic and poetic types that comprised his friends in Houston in the mid-60s.

After wading through a few of the tapes – which I found very disturbing for a variety of reasons – I faced the difficulty of finding a focus for writing about them. The immediacy and intimacy of eavesdropping on selected slices of the life of a dynamic community invites an emotional interaction between the imagination of the listener and what is revealed on the audio. Using this historical resource differs greatly from the reading of scholarly analyses or even first-hand accounts of survivors. Each listener will come away with unique insights based on one’s expectations and visualization of the scene.

I decided to compare two recordings from the point of view of someone who was acquainted with Larry before he joined Peoples Temple. My impressions might differ from the perspective of others because I was looking for evidence of Larry’s state of mind expressed through his words and voice.

Several factors contribute to the sense of crisis preserved on tape Q 635, the first of several tapes from the White Night of April 12th, 1978. These include the denial by the Guyanese government of a medical license for Larry, who by then was Jonestown’s medical doctor, an impending press conference via radio to answer new accusations from the Concerned Relatives in San Francisco, and worst of all, the fear that action will soon be taken to enforce the custody ruling in the John Victor Stoen case. To an outside observer, with all of this going on, the “tawdry little interrogation” [1] of Stanley Clayton seems a petty and bizarre concern.

It seems that Stanley has been called before the gathering to answer charges that he cheated on his girlfriend, Janice, with a white woman. It also seems that Jim Jones has decided that, in order to punish Stanley, Janice should now “relate” to the doctor, Larry Schacht.

The events recorded on this tape bring up such strong emotions that I cannot approach them with any kind of scholarly detachment. I feel an impotent rage as I listen. Stanley seems an easy target for humiliation, and I feel embarrassed for him as his exploits are offered up to the community as a cheap source of amusement. I feel an even stronger anger at Jim Jones’ casual and disrespectful manipulation of the personal lives of the members. I bristle at his egotistical assumption that he has the right to usurp their choices, and that he can demean the power of their sexuality so that he can use it for his own ends and salacious entertainment. Jones takes several opportunities during this discussion to indulge in a long, rambling and vulgar monologue on sex and relationships, at one point referring to himself as “the maestro of revolutionary sex!” After much questioning and cajoling of the young Janice by Jones and some of the audience, it becomes obvious that, despite Stanley’s shortcomings, she prefers him to the doctor. The community then moves from the specific to the general as they philosophize about the possibility of love relationships in a revolutionary society.

Some of the women encourage Janice and others to have respect for themselves and to break free of the slavery of demeaning relationships. One of the men agrees saying, “[T]he thing that you need to do, and a lot of sisters need to do, is stand up on your own two feet.” Another voice labeled “Man” also makes several comments on this topic, at one point saying: “A lot of you are in relationships, you think you’re wanted. But you’re not wanted. Nobody’s wanted… You’re needed. And that’s something you’re going to have to recognize.” I recognize the voice as Larry’s and, despite its cynical tone, am relieved to hear the passion that I remember was once used to express rebellion against war and oppression.

Analyzing the tape at this point becomes difficult because at times the sound cuts out or is covered by other noises. The listener has to guess at parts of conversations and piece them together, sorting through the threads of several issues being addressed during this gathering. I listen to the tape and read the transcript several times in an attempt to follow the progression of this story within a story, and perhaps my emotional reaction colors my interpretation of underlying issues.

One of the subplots in the ongoing interrogation of Stanley is the character of Janice and the focus she provides for the issues of the night. She speaks quietly and is obviously embarrassed by the questioning. But my concentration on this unfolding little drama is of course on Larry and my sense that he, unlike their leader, would never force himself on someone who does not want him. After more questioning, mostly by Jim Jones, Janice eventually concedes that she does “feel something for the doctor, because – Okay, last night, when I was talking to him, he didn’t – he showed his sensitivity to me,… – so like um, he – you know, he even told me, you know, why don’t you just go on home, ‘cause I know you’re tired.” Interestingly, as soon as Janice seems to waver in favor of the doctor, Larry steps in with his own statement. I can hear the familiar fire and anger in his voice, tinged with a new bitterness as he says:

Life is shit. And Dad’s been saying a long time, that any life outside this collective, is shit. And what he – What Dad says about relationships is true, too, every – every bit of what dad says is true about it. And I’m grateful to him for teaching me, because I’m not getting involved with a relationship, because I hope – ‘cause I want to die a revolutionary death.

In his next utterance, however, the longing and loneliness in his voice is obvious: “And I– I believe– I been– I’ve been (Pause) hesitant and afraid, but boy it looked good. It looked good, it looked good.” Even though his words are sad, I sense a certain triumph in them. Is this a subtle way to retain some control of the situation? By using Jones’ own argument in favor of “revolutionary death,” has he found a way of not going along with the arrangement? This is mere speculation on my part, but I like to think Larry retained some small bit of resistance to authority. Even though he was part of the leadership of Peoples Temple, at this point Larry had not completely lost his humanity. Of course, in light of his subsequent actions in November, this small instance of independence and decency might seem a trivial concern.

In many ways the 29-year-old Larry on this recording sounds very much like the boy I knew. What is missing is the complexity, the sensitivity and idealism that once lit up his spirit, leaving only cynical anger in its place.

We hear a very different Larry on Tape Q 182, recorded on October 9, 1978, six months after the White Night recording, just a few days after Larry’s 30th birthday, and six weeks before the deaths. This was actually the first of the tapes I chose after reading some of the transcripts because Larry seemed to be featured prominently at this gathering of the community. It was with great anticipation that I clicked on the recording, imagining that hearing his voice would be like a communication across the decades. However, even as he exhaustively recounts instance after instance of Jim Jones’ healing “miracles,” I am disappointed at the lack of energy in his voice. The only remnant I hear of his once-expressive intonation is the emphasis he places on certain words that are indicated by italics in the transcript. In contrast to the earlier tape, his voice sounds high-pitched with no depth of emotion, and his tone is mostly flat.

As one of the first authors to listen to the audiotapes, James Reston Jr. had a harsh assessment of Larry Schacht. In his 1981 book, Our Father Who Art in Hell, he refers several times, with obvious disdain, to the Jonestown doctor as a “fabulist” who steps in as needed to bolster the extravagant claims of Jim Jones.

Being enlisted to back up their leader’s grandiose assertions perhaps explains the lack of energy or conviction in Larry’s voice. However, it is not just his tone that sounds wrong. Hearing my once skeptical Jewish friend speak of Jim Jones in Christ-like terms is jarring. Larry warns those who “don’t accept Dad as their savior” and reminds them of “Dad’s” injunction to those who would be healed: “look to me and live.” The interesting truth is that there were amazingly few deaths in Jonestown before November 18th, 1978. I had read elsewhere that after the membership moved to Guyana, the theatrically-staged faith healings which had once been such a dramatic feature of Peoples Temple services were no longer on display in Jonestown. These events had always been an effective way to draw in new members, which of course was no longer necessary in their jungle isolation. Perhaps Larry’s address to the community on this night was meant to be a reminder of those former times, a reminder that “Dad’s” healing power was undiminished. Maybe this explains why Larry sounds as though he is speaking by rote and, if you listen carefully, seems to hesitate at times while Jim Jones’ voice can be heard in the background, prompting him.

Larry’s jarring use of Biblical language continues in his references to “Babylon” and “those who look back to Babylon.” Although he is merely echoing Jim Jones’ terminology, when I first saw this on the transcript, I wondered if Larry thought of me as part of the Babylon of America, one of those lost in the illusions of a decadent society. Or did he ever think of me at all? Hearing these words on the tape – not in Larry’s deep clear voice, but spoken flatly, as if memorized – makes me realize with great sadness that it is he who is lost, he has lost himself.

What is even more sad is that after Larry’s reference to Babylon, he castigates “those who… think they have their own life to live.” This statement is a stark indication of what was expected of those who joined Peoples Temple. Although many, like Larry were given the opportunity to follow their revolutionary dreams, it is also true that they no longer had “their own life to live.” This declaration is a chilling reminder of another of Larry’s statements, not spoken but typed by his own hand, “[T]he more I hear and learn about the real events in the world the less I tend to be Illusionary about life. Thank you for pointing out that I am holding on to life too much.” These are the words of a young man, not yet 30, typed up as part of the incriminating “Cyanide Memo” to Jim Jones. I am not sure of the date of this memo, but because of the references to Deborah Layton’s defection, assume it was written shortly after that traumatic event in May of 1978. If so, that perhaps explains why there is so little passion left in his voice by that night in October recorded on Q 182. Sadly, by November, Larry would have had time enough to let go of his final “Illusionary” ideas that life was worth holding on to – time enough to deny the medical training and human instinct to save life rather than to take it.

Footnote

[1] James Reston, Jr., Our Father Who Art in Hell: The Life and Death of Jim Jones (New York: Times Books, 1981) 262.