“Jonestown” has come to stand for a failed American narrative, a failed utopian dream, a dream deferred. It was the mass murders and suicide of more than 900 people in an isolated jungle in Guyana. This happened over 33 years ago. Much has been written about it: testimonies of survivors, news reports, books, articles, movies, documentaries, even plays and novels have emerged. Passions around this event ran high. Annual memorial services have been held. A Jonestown website has been established at a university. A memorial wall has been dedicated. A new generation who never knew Jonestown has come to adulthood. Some survivors have died, others who were once silent are beginning to speak. Tensions exist within and between former participants, family members and survivors, on the one hand, and the new generation of those who were not there, on the other. Different versions of reality are emerging.

What should we believe? If memories of Jonestown are being passed on then who ought to speak? What stories should to be told, revised or withheld? What more can be said? These reflections are about these questions.

Memorials:

May 29, 2011 marked a decisive turn in the way we remember Jonestown. A group of about 150 survivors, former members of Peoples Temple, relatives of the Jonestown dead and friends met at the Evergreen Cemetery, Oakland, California in the afternoon of this Saturday to dedicate four granite plaques with the names of the Jonestown dead. According to Fielding M. McGehee III, “The memorial itself consists of four granite plaques laid side-by-side on the hillside where 409 unidentified and unclaimed bodies from the Jonestown tragedy rest on a mass grave.” Unfortunately, I was unaware of this memorial event. I was not present. I want to capture the sequence of my memory. I will begin with November 18, 2011. Then I shall return to comment further on this May 29th event. Perhaps a painful tension and split within the Diaspora Peoples Temple and Jonestown community and friends will be revealed.

Friday morning, November 18, 2011:

I was present at the 33rd annual memorial service to commemorate the Jonestown dead on Friday, November 18, 2011. It was an overcast morning at the Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland California. It had rained earlier. One person commented to me, “Finally, the rain has stopped!” About 28 people had gathered for the memorial service. A camera crew was present, and so were several other individuals with recorders, telelens and hand held cameras. Fewer still appeared to have been the direct descendants of the tragic Jonestown legacy. I recognized at least one other person, Rev. Dr. Jynona Norwood, CEO of Cherishing the Children/the Guyana Tribute Foundation and senior pastor of Family Christian Cathedral in Inglewood, California. She has been the organizer of the annual memorial service since 1979. Rev. Norwood lost 27 family members at Jonestown.

I wondered, where had all the people gone? In the early 1980’s there were upward from 50 people in attendance. There was singing. Instruments played. But today the audience was quiet. There were no instruments. It was the smallest gathering I had seen. What was going on? The numbers are dwindling, I thought. Before the service was over, the camera crew had departed. Has everything needful already been said?

What more can we say today about this tragedy that happened more than 33 years ago in the remote jungles of Guyana? I anticipated certain questions: Each year we meet. “But, why do we continue to gather?” Each year words are spoken. “What would be said this time?” Each year this crowd size dwindles. “Where will the focus be today?” I looked around. The sign posts hung on the surrounding iron rod fence announced the day’s focus. One sign post read in part, “The 33rd Official, Annual Jonestown Memorial Anniversary.“ Another read, “Remember the Innocent Children.” Yet another read, “Don’t honor Jim Jones, honor the children.”

Denouncements of Jim Jones were frequent throughout the service. He was castigated as “insane,” “mad,” “crazy,” “murderer of innocent children,” “the embodiment of evil,” Rev. Norwood equated Jones with Osama Bin Laden and Adolph Hitler (Schreiber, 2011). The focus of this memorial service was on celebrating the lives of the children, their families, Congressman Leo Ryan and his news crew. Those sentiments were also voiced in the other speeches.

Rev. Norwood had always been vehemently against including the name of “James Warren Jones” on the memorial stones, and filed a lawsuit to stop it. This attempt was unsuccessful.

I noticed that the slow dropping away of people at the memorial service could be part of a silent and silencing process. It raised further questions: “What will be remembered?” “What role will social amnesia play?” Silencing is a way that social amnesia comes about. When fewer people every year gather to remember the complex details of an event or even the event itself, then social amnesia succeeds. Eventually, no one is left to remember and tell the whole story. I recall certain words attributed to Martin Luther King Jr., “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter” (Context, Cover page). At the end of the service, the organizer asked us to come back next year.

I hope to do so. There is much more to say, and no one discipline (i.e. theology, psychology, sociology, anthropology, history, etc.) can say it all. “Jonestown” as an event is immense and has roots in everyday life, the soil of American history, social movements and the human condition. We need the collective minds of many thinkers to help interpret and wrestle meaning from this complex event. It bleeds into other events and continues to influence us over time, whether remembered or not. No one view or single perspective can adequately address all the concerns.

Black Draped Cloth: Symbol of a painful tension.

Following the deaths in Jonestown in 1978, some individual bodies were never identified, especially among the children who perished that fateful day. There were also a number of bodies which were never claimed by their families, or who had no families to claim them. These comprise the 409 bodies buried at the mass grave at Evergreen. Now, more than 30 years later, the names of all 918 people who died are known, and the four granite plaques which were placed at Evergreen the previous May lists them all. On this day, however, a black cloth with red lining was draped over them. Did the black draped cloth serve as a unifying symbol for all of the names, unidentified and unclaimed bodies, on the plaques? I wondered about its symbolism and meaning. Perhaps, this idea of a unifying symbol was my own romantic spin.

Was the black cloth draped over the new Jonestown memorial to cover it, a refusal to acknowledge the existence of the plaques? Further information from news reports of the new Jonestown Memorial from last spring suggests that to be the case, that the black draped cloth represented a painful tension and dispute concerning the names to be included on the memorial plaques.

Meanings can be multi-dimensional. The black draped cloth may serve as metaphor for a break with the past. It may represent an option to forge a different, alternative path. As metaphor, the draped cloth may serve as denial, concealment or attempts to cover over certain realities. It may also provide opportunity to insert one’s own account of things or forget them all together.

On Saturday, May 29, 2011, the Reverend John Moore gave the opening and closing prayers to this service of dedication. He acknowledged that God is the creator of everyone. Our commitments to do justice and love kindness is always in need of renewal. By beginning this way, no one is excluded, every future is included. His daughter, Professor Rebecca Moore, who lost two sisters and a nephew was among the participants. She said, “In ten, twenty or fifty years from now and when we are all gone, this tribute will remain to remind the world of that fateful day and the people who lived and died in Jonestown.” Her words will grow in significance as time goes by.

The significance of the Past: What is remembered matters.

I began to think about an address I gave at the Howard Thurman Lectures, Colgate-Rochester Crozer Theological School in October 2008. I frequently return to past ideas that have been triggered by the current situation in which I am living. Reflecting upon a current event with the aid of a past perspective may help us to see or notice some things we might otherwise miss. Time can be revelatory, especially when yesterday’s events sheds more light upon today’s engagements. New and perhaps deeper meanings can emerge. The following is what I said on that occasion in 2008.

Looking back, I wonder what continues to elude us about Jonestown? Was Jonestown prelude or postlude? Or – as I fear – has Jonestown been largely forgotten by the general public and its lessons unlearned? When we fail to learn the tragic lessons of the past, then we are likely to repeat them, unwittingly. In that sense Jonestown is prelude. Are there trends today in our presidential campaign, political and religious life that are reminiscent of the insular society that became known as “Jonestown?” We remember that in the end, Jonestown was characterized by a closed worldview, internecine battles, controlled communication, manipulation of thought, and a diminished capacity of members to think critically about their situation. Jonestown had evolved a closed cosmos and tunnel vision that played their part in sealing the fate of so many.

A new generation has now come to adulthood since the tragic events in Jonestown. I often draw a blank when I ask my theology students about Jonestown. A few have never heard of it. Jonestown was something that happened before they were born. If it did not happen in their life time, then is it myth? How can we transmit the tragic lessons of a failed utopian dream to the next generation of leaders, if we ourselves are lacking in insight and have failed to learn the lessons of the past? In short, it is important to remember. Remembering enables a way to see more deeply and to develop the capacity to look further than immediate needs or conventional wisdom dictates.

It was Jim Jones’ pragmatic interests that sought to make Martin Luther King’s utopian dream come true. Jonestown, in its ideal form, sought to create a utopian community where the barriers of race, class, gender, age and religion would be broken down and no longer serve to divide people into warring camps. But Jim Jones, a charismatic figure, may not have been sufficiently informed or influenced by Walter Rauschenbusch’s emphasis on the operation of supra-personal forces and entrenched moral evil that can invade and cause blindness even in the private sphere. He may not have been sufficiently informed about Reinhold Niebuhr’s realism and concern for collective egoism and corruption.

Howard Thurman, the philosophical theologian, though ill, was living in San Francisco when the tragedy at Jonestown occurred. Looking back, it was Thurman’s ideas about the interrelatedness of all things, call to community, kinship with all life and an ancient quest for harmony that made sense of the appeal Jim Jones held for idealists and social activists of the 1960’s and 70’s. “[T]he organic harmony in the interrelatedness of all creation becomes a part of the quality of life itself, a part of the experienced intent of all living things” (1971:13). Wittingly or unwittingly, Jones had tapped a deep hunger in people that drew them to his vision of a new, egalitarian, just and harmonious society embedded in the American dream. In such a society, Thurman offered the insight that the contradictions of life may not be overcome, but they do not have final say. Something deeper and universal stirs within the human condition and works to transform the powers that separate. This nameless “something deeper” and of infinite varieties can be cultivated and experienced in common struggle against the forces of oppression and work through human cooperation, religious and secular. It can nourish human resiliency. It gives rise to hope and utopian dreams.

But does not this “deeper hunger” that gives rise to utopian dreams also make us vulnerable to exploitation? Certain televangelists and mega church ministries can blind us with promises of prosperity and individual salvation in the here and now. Many souls have fallen prey to the claims of prosperity gospel to satisfy our deepest hungers.Americans want to be made safe, put back on a right track, secure, free and in charge. We all want to be millionaires. We want employment and health insurance for ourselves and kids. If God has placed the care of creation in our collective hands, then we cannot shrug off our responsibility by saying, “Don’t worry about it! God will straighten up our mess for us.” Does not this “deeper something” that is endemic to the human condition make us vulnerable to certain utopian claims in the current presidential campaign? In a few days, Americans will be making a decision, not only for themselves, but for the world, as a whole. The recent bank crisis and my non-American neighbors in London and elsewhere remind me, almost daily, that we share one inter-dependent world, a fragile web of life. What affects one directly affect all indirectly. We still have this lesson to learn (2008).

Though I spoke these words a few years ago, they seem even more relevant today in a Tea Party world. Tea Party politics has its own narrative on diversity, American society, utopian claims and spin on what can save us now.

What story shall we tell to future generations?:

Kenneth C. Davis once asked: “Why should we bother with history?” What difference does a historical consciousness make anyway? A generation of folk have grown up and come to adulthood since the events of November 18, 1978. Some have never heard of Jim Jones, Peoples Temple or Jonestown. Why pass on memories of a perplexing and tragic past? Isn’t it better to say nothing more and “let sleeping dogs lie?” Or, should more be said? This begs the questions: “How shall we remember? Who shall tell the next generation? What should be told or withheld?”

Our collective mind, the role of education, the transmission of knowledge and social wisdom are at stake here. Our futures are at stake. A recent book attempts to address some of these concerns, but there may be some problems worth noting.

As time goes by, the story of Peoples Temple and Jonestown will find its way into fiction, such as The Hunter, by novelist John Lescroart (2012). A new spin is placed on something humanly familiar. Some names and places are embellished, changed, or newly created to explain certain events in an imaginative way. A novel differs from research or investigative reporting where the use of primary and secondary resources are distinguished. Fact, empirical evidence and documentation matter.

In her important and scholarly written book, Understanding Peoples Temple and Jonestown, Rebecca Moore identifies several paths that future studies and analysis of Peoples Temple and Jonestown may take. First, there are the survivors whom Moore refers to as “loyalist,” those who have been silent, but are now ready to speak. Then there are the voices of “those who lived and died while members of Peoples Temple.” Their “voices can be heard on the 900 audio tapes recovered from Jonestown” (page 19). Finally, there is a new generation of people who were not eyewitnesses nor participants, but have an interest in interpreting the events of Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Among them are playwrights, artists, musicians, authors. The latter will play an increasingly important interpretive role to future generations. I comment on this interpretive possibility.

A new and important book on Jonestown has been published. It is important because it holds the possibility of further informing the uninformed, to influence the way familiars remember and tell the story. It is important because it helps determine what passes as “knowledge” and conventional wisdom. But there may be some problems here, too. The book I have in mind is A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Hope, Deception, and Survival at Jonestown, by Julia Scheeres (2011). More must be said about this.

The lens through which one looks at something matters. My concerns are not limited to this book. They can serve to beg the larger question about how the past – any past – is re-presented and helps shape mind and action in future society.

A Thousand Lives is based upon media reports, selected scholarly works, interviews, audiotape recordings and FBI documents. The author states in her introduction: “My aim here is to help readers understand the reasons that people were drawn to Jim Jones and his church… To date, the Jonestown canon has veered between sensational media accounts and narrow academic studies. In this book, I endeavor to tell the Jonestown story on a grander, more human, scale” (page 14). Does she succeed? The book appears to rely heavily upon the important and scholarly work of Rebecca Moore.

The book is entertaining, highly interpretive and uneven. That is to say, it is descriptive, suggestive and anecdotal at points. It presents important ideas (i.e. the great migration) without helpful documentation. It is not scholarly. Fact, fantasy and opinion are not distinguished.

It is not often clear whose voice is speaking, that of the author, a scholarly source, or the one being interviewed, or is this an imaginative interpretation of certain facts? The book begins with a story about Tommy Bogue’s journey to Jonestown. “The journey up the coastline was choppy, the shrimp trawler too far out to get a good look at the muddy shore. While other passengers rested fitfully in sleeping bags spread out on the deck or in the berths below, fifteen-year-old Tommy Bogue gripped the slick railing, bracing himself against the waves” (page 15).

Motives are attributed to behaviors and one may wonder how the author knows these things. For example, on page 148, the author writes, “Jones didn’t want people clamoring to go home for funerals.” This may or may not be true, but how does the author know this?

The author also writes: “Most of his broadcasts dealt with the mistreatment of African Americans, who comprised nearly 70 percent of the community” (page 146). No footnote reference or documentation for this statistic is given. So where does it come from? The end notes suggest that the source is a chapter by Rebecca Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture” (page 58) inPeoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (2004). In that chapter, Moore is citing yet another source, The Relational Self, by this author. Moore writes:

Archie Smith Jr. compiled State Department data on Jonestown victims and published two tables in his book, The Relational Self, which indicated not just a black majority of victims in Jonestown (71%), but a black female near-majority overall (49%). Moreover, almost a quarter of those living in Jonestown (22%) were black women over the age of 51. Smith argued that while the black members of Peoples Temple saw the group providing real services to the community and creating an alternative to the status quo, their vision “was not broad or critical enough to perceive the barriers of class, sex, age and race in the social structure of the organization itself.” He referred to the continuing superior-inferior relationships perpetuated in the movement as racism (page 58).

Scheeres may help readers to understand certain reasons for joining Peoples Temple, how they were deceived and forced to stay, especially after they moved to the isolated Jonestown Commune in Guyana. But such reasons do not help us understand or see how wider and systemic forces have been internalized and played their part to influence the immediate contexts in which people lived. Many believed that they must work for an egalitarian society with liberty and justice for all. How was Jonestown a part of the host society in which followers had membership, played certain roles, held positions, and what they yearned for? These added reasons would be an important part of explaining why some people joined and became committed followers and others did not. I have often wondered why my widowed mother, a religious idealist resisted joining the Peoples Temple Movement. After all, she did receive an invitation to join when Jim Jones visited Seattle. Why did she not go?

Scheeres also stated that “…the Jonestown canon has veered between sensational media accounts and narrow academic studies.” I am not sure to what she is referring, and I am unaware of “the” Jonestown canon, or the existence of only one “Jonestown canon.” Perhaps, this is a part of the undocumented statements I find in the telling of this story. It would be helpful to know what she is talking about when referring to “the” Jonestown canon and “narrow academic studies.”

The author further states, “In this book, I endeavor to tell the Jonestown story on a grander, more human, scale.” Does this description mean hyperbole? I am not convinced that the author achieves this “grander, more human scale.” She does manage to tell a tragic, haunting story in an entertaining way. She makes statements that leave the reader wondering how she or anyone could know another’s subjectivity, especially when they were not present or a part of the unfolding events.

Most emphatically, the book does not attempt to situate the Jim Jones story within a discipline or set of disciplines or tradition for critical evaluation. It does not provide a wider context, i.e., American history, the history of religions, or the history of social movements in America. The author makes reference to “the Great Migration of two million blacks who left the Jim Crow South searching for better lives.” Where does this material of the Great Migration come from? No critical analysis or commentary on the Great Migration as context is provided for the future reader.

How we tell the story matters:

When we tell the story to future generations, they will be too far removed from the passions of the time to be influenced by them. Critical scholarship will continue to be important. The idea of “critical scholarship” is also about good journalism in which fact, opinion and fantasy are clearly distinguished.

How the past is re-presented ought to concern us. The looking-glass lens we use matters. We live our daily lives guided by certain mechanisms called unquestioned assumptions, moral commitments, values and practices. They help us praise some actors and demonize others, navigate bewitching difficulties, give shape and find meaning in our everyday lives. Language and practical knowledge build up and help constitute the conventional wisdom and horizons of the day. The past remembered or not, is ever present. The past and present influence the way we view the future. If this is true, then we are moral agents, truth-builders and architects of present and future worlds. We ought to pay close attention to the way the past is re-presented and used as building block. The remembered past provides material for the shaping of mind and self in society’s future.

This leads me back to a reflection on James Warren Jones and the question, “What more can be said?”

What more can be said?:

Looking back we know more about Jim Jones now than we did when he was active. Then, we had close-up snapshots and descriptions of his activities. Now we can place him – those snapshots and descriptions – in a broader context and in wider historical perspective. Today we can say much more.

James Warren Jones was neither all good nor all bad. He was a complex figure, both decent and cruel. Like with the rest of us, his struggle between good and evil was ongoing. He wanted to confront and push back the forces of social evil by doing good, as he saw it. He was also enmeshed in his own bio-psychological and social matrix and responded to the unfolding challenges of everyday life as he found them in his situation. He, like the rest of us, was vulnerable to anxiety and guilt, fear and shame. Unlike many of us, he took couragous, radical and unpopular stands on issues that matter, issues of social class, economic disparity, race, injustice, and sexual orientation, to list a few. He took confusing and seemingly contradictory positions on religious identity, use of self and power.

He had an unusual ministry and helped a lot of people that others did not help. He tried to address a deep hunger for significance. His ministry embodied all of these things. He never transcended the warring and early wounds of rejection that haunted him all of his life, according to reports about him. In the end, does he become the cruel wound-inflicting monster he most feared?

“Peoples Temple members were engaged in the world, and tried to make concrete differences in individuals’ lives and in society as a whole” (Scheeres, page 18). In attempts to correct the wrongs in people’s lives, do good and be successful, Jim Jones deceived himself and others. He was unable to overcome evil with good, as he understood it. He accomplished a surprising amount of good on the one hand, and perpetrated enormous evil on the other hand. These things happened with the witting and unwitting co-operation of many people. In historical perspective, Jim Jones shows us that no one can transcend the evils they perceive in others or escape the forces of history. This, then, could open the door to consider the counter-balancing role of patience, reflexivity, compassion, repentance and forgiveness in everyday life. But those considerations would carry us far beyond the scope of these reflections. They must wait for another time.

There are always reciprocal and systemic influences we cannot account for. In this way Jim Jones shows us that no one stands alone. No one who strains, as he did, under the heavy weights of social evil is free from delusional thinking, especially when isolated. No one is immune from self-deception. No one is beyond reproach. No one individual can fix it for all the rest of us. Jim Jones shows us what can happen to all of us who promise what cannot be delivered by any of us in the penultimate. He encouraged the expectations of others and tried to fulfill them. But the tasks of attempting to control everything, shoulder it alone, and fill the deficits of the human condition are beyond us. In the end we utterly fail.

The power of questions:

This leads to more reflective questions for the educator, researcher, scholar, artist, musicians, teller of stories, poet, philosopher and theologian. Eschatology is about the end or end-times. It means Christian or religious thought about the penultimate and death. How was eschatology given religious and secular meaning in Jonestown? What are the lessons of Jim Jones, Peoples Temple and Jonestown that we still have not learned and why? Do our religious and aesthetic, educational, welfare and political institutions have a responsibility, in a democracy, to help us with the answers and new learning? If we do not learn the lessons of the past and gain wisdom, then are we likely to repeat our mistakes and perpetuate even greater expressions of evil? How was Jim Jones, other leaders and members of the Jonestown commune trapped and tripped up? What are the lessons to be learned about providing beneficial leadership? Where did the white poor fit into this utopian movement for racial and economic equality? And what about other groups – Asians and other minorities, those who live daily with physical disabilities, those who live with mental illness – where do they do fit in?

The questions we raise are about our shared vulnerabilities, humanity and common destiny; discernment, accurate transmission of information, role of wisdom in a democracy, and best ways to proceed. Our realities are co-constructed, inter-related and multi-layered. The way we come to understand how Jim Jones, Peoples Temple and Jonestown – and ourselves – as integral parts of American and world religious and secular history matters. How does Peoples Temple and Jonestown fit into the history of reform movements in America? How are we, in today’s world of political spin, confrontation, terror and threat of nuclear disaster, vulnerable to the same or similar deceptive forces that claimed Jim Jones and the hope-filled people he led? After all, they too sought and thought they were building a better society for everyone.

It may be that what comes to stand as “truth” is really a matter of marketing strategy. So, the lens through which we view things and tell the story matter. The story with the greatest novel or entertainment value may win the day. But “winning” does not mean that it is a true story. Words of a great 19th Century hymn of the church comes to mind: “Once to everyman and nation,” third verse. “Though the cause of evil prosper, yet ‘tis truth alone is strong; though her portion be the scaffold and upon the throne be wrong. Yet that scaffold sways the future, and behind the dim unknown, standith God within the shadow keeping watch above His own” (1955, page 361). True, the sexist language in the hymn is unfortunate.

Truth, or whose “truth” will sway or determine the future, is an important distinction. “God standing within the shadow keeping watch above His own” leads to questions about suffering and divine providence. Providence is a belief in God’s ultimate goodness and power at work in everything (1975:81). This question about divine providence was of great importance to many African Americans who died in Jonestown.” Such a belief in ultimate providence is essential to the consistent affirmation of the goodness of life” (1975:81). And it is a practical expression of theology when it keeps the believer’s hopes and creativity alive even in the face of seemingly hopeless circumstances. Some believed they were doing God’s will by deciding to work for an egalitarian social order with greater justice than the one they left behind. They were answering the deep human cry for redemption and true community. “Though the cause of evil prosper it is truth alone that is strong.”

It is this ideal of a strong providential truth over falsehood that needs wide and on-going conversation. Speaking of African American slave religion, Henry H. Mitchel argued “their track recording the African Experience, and in American slavery and oppression, forces the most extreme cynic to take a second look” (1975:82). The metaphor and message about “truth on the swaying scaffold,” the future and the basis for decision making are relevant and timeless religious themes. Hence, we would be wise to ask, “What truth, or whose truth will sway the future?” Divine providence and the triumph of truth as eschatological themes are central to traditional African American religious sensibilities.

How can we make true, wise and self-conscious decisions about the future, take courage and raise reflexive questions if we do not ponder them anew? How can we claim to be immune if we do not even comprehend the magnitude or complexity of the problems that face us as moral agents? One would hope that discerning and reflexive questions and a sense of history, our wisdom traditions and scholarly disciplines would inform critical interpretations of what happened and why. Such concerns might helps us act with courage in the present, with greater wisdom and deeper compassion. Perhaps we will still have light sufficient to help build a better society. What more, then shall we say about this? Where do we go from here?

References:

Davis, Kenneth C., Don’t Know Much About History. New York: Perennial Books: HarperCollins Publishers, 2003.

The Hymnbook, Richmond, Va.: Presbyterian Church in the United States. 4th Printing, 1955.

King, Jr., Martin Luther, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? Boston: Beacon Press, 1967.

Lescoart, John, The Hunter: A Novel. New York: Dutton, 2012.

McGehee III, Fielding M., The Campaign for the New Jonestown Memorial: A Brief History.

Mitchel, Henry H., Black Belief. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1975.

Moore, Rebecca, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (editors), Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America. Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 2004.

Moore, Rebecca, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Westport, Ct.: Praeger Publishers, 2009.

Scheeres, Julia, A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Hope, Deception, and Survival at Jonestown. New York: Free Press, Simon & Schuster, 2011.

Schreiber, Dan, “Lawsuit Targets Jonestown Cult Leader’s Name on Oakland Massacre Memorial.” San Francisco Examiner. May 12, 2011.

Smith, Jr., Archie, “Reflections on Howard Thurman & Psalms 8,” Annual Howard Thurman Lectureship at Colgate-Rochester Divinity School. Posted on the Pacific School of Religion Website, March 4, 2009.

Thurman, Howard, The Search for Common Ground: An Inquiry into the Basis of Man’s Experience of Community. Richmond, Indiana: Friends United Press, 1971.

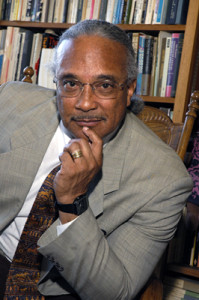

(Rev. Archie Smith, Jr., Ph.D is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. His previous articles are here.)