Any attempt to know the entirety and variety of the materials constituting the public library in Jonestown, a community lost to the jungle a third of a century ago, is in one sense doomed to failure. We can’t even know the number of titles missing from the record of 112 that Nicola Bergström Hansen has brought to light through study of existing records, largely the trove of library cards released by the FBI through a FOIA request. Of the titles we do know, we cannot determine the number of copies the library possessed of each or the frequency with which each circulated. But even after acknowledging those factors plus others not yet enumerated, what she has accomplished with creative scholarship is enormous, and innovative and causes me, a defector from Peoples Temple who is also a public librarian, to feel deep gratitude. One hopes that her work will provoke still living survivors of Jonestown to recall other titles that have so far gone missing as well as more perspectives on the various roles which the library must have played in the life of Jonestown’s inhabitants. Certainly if anyone can shed light on the process by which these books were acquired, this small but integral and revealing part of the historical record of Jonestown can be clarified.

Any attempt to know the entirety and variety of the materials constituting the public library in Jonestown, a community lost to the jungle a third of a century ago, is in one sense doomed to failure. We can’t even know the number of titles missing from the record of 112 that Nicola Bergström Hansen has brought to light through study of existing records, largely the trove of library cards released by the FBI through a FOIA request. Of the titles we do know, we cannot determine the number of copies the library possessed of each or the frequency with which each circulated. But even after acknowledging those factors plus others not yet enumerated, what she has accomplished with creative scholarship is enormous, and innovative and causes me, a defector from Peoples Temple who is also a public librarian, to feel deep gratitude. One hopes that her work will provoke still living survivors of Jonestown to recall other titles that have so far gone missing as well as more perspectives on the various roles which the library must have played in the life of Jonestown’s inhabitants. Certainly if anyone can shed light on the process by which these books were acquired, this small but integral and revealing part of the historical record of Jonestown can be clarified.

So what do we find in this admittedly-partial list which Ms. Bergström Hansen has arranged alphabetically by author? With a few marked exceptions such as Richard Ellman’s The Identity of Yeats and Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, these are intended for a popular and not particularly well-educated audience. The adult non-fiction which comprises the bulk of the material we know about ranges from the very practical of learning how make a living from the thin soil of a rain forest, represented by a host of titles – few of which dealt directly with the tropics, perhaps because of the dearth of available ones – to revolutionary propaganda with a strong bias towards the Soviet Union, permeating a host of subject areas.

This crowd of books leaves a little elbow room for extremely mainstream fiction and dishearteningly few dead-white-male (or female, for that matter) classics in sight. Those expecting at least one volume of Shakespeare will be disappointed but not surprised. There’s not a single work of the Ancients either – no Homer, no Herodotus, no Plato, no Aristotle, no Cicero, no Vergil, no Augustine – even in an abridged version. Jonestown seems to have existed in a place where all but the very recent past hadn’t happened or simply didn’t matter. However, a few writers of classic fiction – five by my count, two of them African-American, all of them male – managed to survive in this ahistorical literary wasteland with one work apiece represented in the collection. The most destitute public library back in the USA probably held more classics than the Jonestown public library could claim.

As far as popular fiction is concerned, the best represented segment is definitely science fiction, which must have had a strong constituency in Jonestown whose residents generally thought of themselves as creating the future themselves from a history that was almost entirely in the present. And so we find four titles by Robert Heinlein and one – Dune – by Frank Herbert. There’s room for improvement, of course. Even the most avid SciFi fan can’t be expected to read those same five titles forever unless it be for a very brief lifetime.

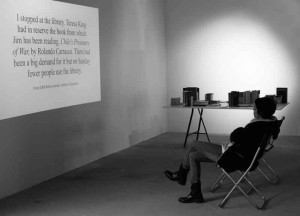

The general absence of female authors is puzzling given that the librarian, Teresa King, saw herself as a radical feminist. Her personal bible, Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialetic of Sex, is noticeably absent, though it was one of the books sold at the Temple’s book table in San Francisco and Redwood Valley, as Michael Klingman, the table’s manager and selector of titles, recently assured me. Women’s Liberation and Literature, edited by Elaine Showalter, provides the only evidence of a direct feminist consciousness. Unless, of course, one wants to include Elizabeth Gurley Flynn’s Stalinist autobiography in that category. Did Teresa simply lack the authority to place more works with a feminist analysis on the shelves? Or did she suffer as a part-time librarian from an almost complete lack of funding, forcing her and those others who worked with her to accept whatever titles came their way, so long as the copies were in decent shape, some freely donated, others emptied – as many of them may have been – from the suitcases of new arrivals?

Being well acquainted with the strong opinions held by my friend Teresa, I realize she couldn’t have rested happily with the poverty of the shelves. Having finally found paradise, she would have felt duty bound to serve as more than custodian for a vacant room. She knew the power of books and the importance of places that made them available to a wide public. For years she had worked at Kepler’s, a favorite haunt of Stanford intellects. Almost as much as City Lights in nearby San Francisco, it had been responsible for the paperback revolution on the West Coast.

The paucity of books didn’t need to be. I personally donated more than a thousand volumes to the Temple’s stateside library, but none show any evidence of having made the long voyage of Jonestown’s library. I wonder how many other personal libraries didn’t make it to the Promised Land. I also wonder how many books were confiscated upon arrival and never ended up on the shelves of what became a de facto concentration camp. Survivors who were present will no doubt know better than I.

Despite the generally barren landscape, there are happy surprises. The small cadre of children’s books is top notch, hardly dictated by political prejudice. Teresa loved kids and obviously put her heart into the careful selection. I wish she had been allotted more money to expand that collection to the size it deserved. Nonetheless Stuart Little seems to have lived and probably thrived in Jonestown. So did The Berenstain Bears and characters of at least one book by Laura Ingalls Wilder. Alice is happily absent from this Wonderland, but equally happily The Wind in the Willows, a much more democratic work of the imagination, turns up.

Where the selection turns to the matter of educational theory, we find – sadly but predictably – Why Johnny Can’t Read But Ivan Can. At least to my relief, Neil Postman’s Teaching as a Subversive Activity has its say. The work of the great Brazilian educator, Paolo Freire, however, which should have been in such a collection, is notably absent. Despite Jonestown’s proximity to Brazil – a country where Jim Jones, his family and that of Jack Beam also lived for several years in the early 1960’s – Freire’s writings seem to have been excluded for the simple embarrassing reason that they were not originally written in English.

The dearth of titles originally written in other languages and translated into English is revealing not only of a decided monolingualism but also of a certain cultural parochialism that contradicts the Temple’s aim and self-image of diversity and inclusiveness. It was Nicola Bergström Hansen who pointed out what should have been obvious to me in a recent email exchange: Almost every author is indeed Anglo-American, writing in English. One of the three obvious translations, Beckett’s Endgame, an English version of the French original, is the product of a conscious escape from Anglo-Irish culture. Another is what seems to be an undistinguished thriller, War for an Afternoon, by Jens Kruuse, a minor Danish writer. The third is Rolando Carrasco’s Communist party-line tract, Chile’s Prisoners of War, published in Moscow by Novosti Press Agency. The final translation – the only one in the collection that’s not immediately obvious as such – is a biology text by A.G. Loewy, Cell Structure and Function, translated from the German.

Then there are the inspiring anomalies. Whether by intent or through generalized chaos, the Jonestown library seems to have acquired a number of books that ought not to have been on the shelves, at least from the generally orthodox perspective that Comrade Jones shared with the Soviet embassy. High Tory, Evelyn Waugh, rumored to be more Catholic than the Pope and certainly an admirer of Mussolini and Franco, is represented by Decline and Fall. Dorothy Sayers, whose similar Tory views were never a secret, is present with a gripping mystery that even a potential censor evidently couldn’t put down. So, of course, are writers who faithfully followed the Communist Party line: Canadian environmentalist Farley Mowat and San Francisco attorney Vincent Hallinan immediately come to mind. The latter’s self-congratulatory A Lion in the Court was apparently on the reading list, no doubt because he had been helpful to what Jones referred to generically as “The Cause.” Then there’s Daphne Du Maurier’s beyond bourgeois/pseudo aristocratic but extremely popular Frenchman’s Creek, which should have gone to the guillotine but obviously didn’t. I suspect those in authority had too little time to notice or do more than notice and shake their heads. Another apparent anomaly bears mentioning: Hedrick Smith’s The Russians, a conventional capitalist overview of the Soviet Motherland, was perhaps intended to prepare Templars for some unhappy surprises in the great expanses of Siberia, and was therefore spared censorship. Who knows?

What’s most notably lacking in this collection, given the religious history and underpinnings of Peoples Temple, is what might fall under the heading of the religious or spiritual. There does not even appear to have been a copy of the Christian Bible, much less one of the Koran, the Bhagavad Gita or the Tao Teh Ching. Whether Jim Jones still kept a reserve copy of the trusty King James Bible to throw around or threaten to use as toilet paper is unknown but dubious. Back in the States he relied on multiple copies to defeat fundamentalists at the game of scripture quotation. The only arguably “spiritual” title we know of that made it into the Jonestown library was PSI: Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain by Sheila Ostrander, no doubt allowed because it glorified an unexpected accomplishment of Soviet science. Jung’s work on synchronicity, a subject that fascinated Jones, which had been sold at the Temple’s book table in California, is not part of the inventory we so far have. It relied heavily on astrological reasoning that involved the sophisticated interpretation of charts, a practice that JJ reviled in public but practiced in private, retaining his own astrologer, Tish Leroy, until the end.

If this library catalogue had reflected an earlier incarnation of Peoples Temple, the one which I encountered in the spring of 1966, there would have been at least one biography of Gandhi, likely that by Louis Fischer, plus a selection of quotations from works of the Mahatma such as that I used to teach a much earlier authorized course in non-violence. Jones’ professed reverence for the path of satyagraha was reflected in his choice of “Gandhi” as the middle name of his natural son Stephan. By the time the foundations of Jonestown had been laid, nevertheless, there was no longer any place for the turning of the other cheek. Enemies were no longer even to be forgiven.

There seems to have been some attempt, however pathetic, to build an African-American collection that actually begins its story in Africa, attested to by the presence of John G. Jackson’s Introduction to African Civilization and Keith Irvine’s Rise of the Coloured Races. Otherwise what we find are a few basic works by Frederick Douglass and W. E. B. Du Bois, fiction by Ralph Ellison and Richard Wright… and nothing that I can see by a black woman. Though the selection is better than the proverbial nothing, it consists at best of appetizers.

With the exception of a book on the history of the Bill of Rights, the political selections are drab. Where are Marx, Lenin, Luxemburg? Missing in action. Even the Fischer biography of Lenin, passed around by Temple members wanting to see the shaven face of Lenin that so resembled his alleged reincarnation, Jim Jones, or that of Lenin’s mistress Inessa Armand, a spitting image of his wife, Marceline Jones, doesn’t seem to have made it to the jungle encampment. Neither Malcolm X’s autobiography, which had been required reading material back in the States, nor The Glass House Tapes, possibly the most popular title sold at the book table, made the journey to Jonestown. Nor is there any direct evidence of Che Guevara, murdered less than a thousand miles away in jungle little different from that by which Jonestown was besieged. Michael Klingman noted that the Temple book table carried My Life by Trotsky, viewed by orthodox Stalinists as a traitor but by Jones with reserved affection. Michael also informs me that the only title Jones directly banned from the book table was the autobiography of Cheddi Jagan, whose first democratically elected government of Guyana had been overthrown in a CIA-orchestrated coup. No evidence of either of these volumes is present in Jonestown.

Hardly anything that one might turn to for theoretical understanding of Comrade Jones’ strategic plan is present in the inventory we have. The two exceptions consist of the primer from which I’d once taught a divinely-mandated class in socialism, Leo Huberman’s eminently orthodox Introduction to Socialism and G.B. Shaw’s unconsciously high camp An Intelligent Women’s Guide to Socialism, the product of an elitist Fabian who praised Stalin to spite the British ruling class. Might records of any potentially suspect titles have been removed in advance of Congressman Ryan’s visit? One title that wasn’t removed – Fred Schwarz’s infamous right wing tract, You Can Trust the Communists – is a curious one. Might it have been included for two separate but mutually reinforcing reasons: that it might help Templars understand the mindset of their enemies and at the same time put those enemies off track? It also might have been a leftover of the alliance of convenience which Jim Jones negotiated with the head of the John Birch Society in Redwood Valley.

What we do have, inter alia, are numerous exposés of the corporate-military basis of US foreign policy, among them the previously-mentioned Chile’s Prisoners of War, published in the Soviet Union. A number of titles deal with questions surrounding the death of President Kennedy, covering to my slight initial surprise both sides in the highly sensitive debate. To match the conspiracists and/or to provide cover for any future inspection, Jim Jones paranoid mind may have found a place here for the official version in the form of William Manchester’s ever-so-conventional Death of a President. Could its signal presence have been intended to soften the impression left by several works by former insiders on the workings of US government organizations responsible for intelligence gathering and covert operations? I note in this regard titles by Philip Agee and Victor Marchetti.

There’s much else left out of this library that we’ll probably never know about. But what we do know is that this was hardly the sort of institution that could have nourished another Lincoln, by which I mean that it could never have fertilized the development of the sort of well informed citizens for which public libraries had first been created by New England abolitionists, citizens who would be capable to taking cooperative responsibility in a democratic state. In tragic fact, even a library in the rural outback of the Soviet Union or the badlands of the American Deep South would probably have had more to offer the reader than this artifact almost lost to the jungle but for the curiosity and commitment of a graduate student in Sweden who was not even alive when Jonestown ceased to exist.

(Garrett Lambrev is a frequent contributor to the jonestown report. His previous writings may be found here. He can be reached at garrett1926@comcast.net .)