Reprinted with permission

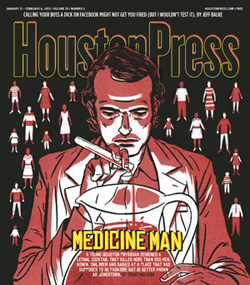

(Craig Malisow’s story, “Jonestown’s Medicine Man”, is reprinted with permission of The Houston Press.)

My story begins – as many do – in a used bookstore in the Milwaukee airport. I was heading back to Houston after visiting family, in November 2012, and had time to kill before my flight. As is my M.O., I made a beeline for the true crime section and scanned the titles. One jumped out me. It was the first time I’d seen a Jonestown book in a true crime section (and believe me, I’ve spent more time than is probably healthy in there) so I took a look.

The first thing I looked for in Guyana Massacre, by Washington Post reporter Charles Krause, was the date of publication. It was December 3, 1978, about two weeks after the incident. Incredible. I picked it up more for what I thought would be the novelty factor of owning a long out-of-print, exploitative “quickie.” I had no idea that this book would, over the next few months, kick off an obsession.

You could make an argument that publishing the book so quickly was an opportunistic money-grab, but the content itself is anything but exploitative. It rekindled my interest in Jonestown, and when I looked for what else I could find online, I of course found the Jonestown Institute website. From that point on, I was a goner.

A few months earlier, a colleague had briefly mentioned Larry Schacht, a native Houstonian, in a story about some of the darker days of the city’s past. And when I checked out Julia Scheeres’ A Thousand Lives, I saw that she devoted a few pages to the “Jonestown doctor.” But I thought there had to be more. I caught my editor on a good day, and she agreed to let me write a story about Schacht.

Ultimately, I don’t know how successful I was. After all, I think I was on a fool’s errand of trying to explain the unexplainable. Moreover, Schacht’s brother and two of his old Houston buddies – three people who would be able to shine a light on his pre-Peoples Temple life – didn’t want to talk. As a reporter, I found this frustrating; as a human being, I found it selfish. I can understand the desire to not want to talk to an absolute stranger about your friend or sibling who conspired in mass murder, but as far as I could gather, these people hadn’t shared anything with anyone. Yet, incredibly, people who had survived Jonestown – people who were there – were opening up to me about the most tragic events of their life, trusting me (as they had trusted other reporters) with unbelievably sensitive material. If these people could talk, why couldn’t these three, so far removed from the events of November 1978, share what they knew about Schacht, in the event that it might be of import to survivors? I believed then, as I do now, that they owe that much to history.

Ultimately, I don’t think my story uncovered anything that former Peoples Temple members didn’t already know about Schacht. But I hope that, on some level, it connected with readers who were either too young to have even heard of Jonestown, or with those who could only equate the tragedy with a punchline.

I’m fairly certain that, even if I hadn’t found Krause’s book in an airport bookstore, something else would have reawakened my interest in Jonestown – but probably not with the same immediacy, and not to the same degree. That little book – published when there was still so much to learn – was the right thing at the right time for me to begin a quest to truly educate myself on a singular event in American history that has largely, and curiously, faded from our collective memory. It gives me the hope that my little story can be the right thing at the right time for someone else to wade into these waters and find something new and profound, something that serves to honor the memory of all those who were taken away.