(This article is adapted from a chapter in Catherine Abbott’s master’s thesis-in-progress at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Catherine Abbott is a regular contributor to this site. Her full collection of articles is here. She may be reached at catherineabbott@yahoo.com.)

Background

Although in many ways outwardly similar to a traditional Pentecostal church, Peoples Temple from the start contained radical political elements. Reverend Jim Jones, a loyal supporter of Marxism, communism, and socialism, used Peoples Temple as a cover to promote his radical agenda, claiming during Peoples Temple’s later years to have infiltrated the church with his unorthodox beliefs. These radical ideas formed before Jones established Peoples Temple and persisted until the very last day of its existence, moving closer to the forefront with each passing year. Jones’ sermons began with communalist and socialist ideas with occasional mention of Karl Marx’s ideas. After migrating to California, the Temple became more active politically as Jones spoke out against capitalism and began to push a more radical agenda. By the time the group migrated to Jonestown, Jones actively pursued his socialist dream, establishing a commune in the jungles of Guyana. Jones implored his followers to commit to his radical plans as well through participation in socialist classes and community meetings in Jonestown. On November 18th, 1978, the day of the mass murder-suicides in Jonestown, Jones proclaimed that the act was to protest capitalism, fascism, and other perceived evils in the United States.

Communalism in Religious Organizations

Modern socialism emerged in early 19th-century Europe as a response to wealth disparity created by industrialization and urbanization. Some members of society welcomed capitalism but others dissented, leading them to socialist philosophies. Rather than individualism, the socialists emphasized collectivism, working for the greater good within their communities, and cooperation. The socialists were concerned with unequal distribution of wealth. When peasant wages fell the workers moved into urban areas and took low-paying jobs. These concerns led socialist thinkers such as Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen to build the ideas behind utopian communes that would emphasize “harmony, association, and cooperation” through communal living and working.[1] These communes existed long before Reverend Jim Jones would build Jonestown in the jungles of Guyana; therefore Jones’ utopian dream was not a new one, but rather part of an experimental socialist lineage conceived at least a century earlier.

Aristocrat Henri de Saint-Simon (1760-1825) was greatly influenced by the French Revolution of 1789. Like Jones, Saint-Simon was interested in social justice. The French philosopher believed that the semi-feudal relationship that still existed in Europe in the early 19th-century was problematic. Saint-Simon’s goals were to “eradicate poverty and to ensure that all benefited from education and employment,”[2] goals Jones agreed were important to pursue in a socialist commune. Saint-Simon also argued that “all men ought to work” in response to the disparity between the “workers” and the “idlers (a group in society who lived off of their wealth without contributing to production or distribution of goods),”[3] a statement Jones supported, as all of the members of Jonestown worked to sustain the commune in Jonestown.

Charles Fourier (1772-1837) took a slightly different approach to the problems of society, blaming the “stifling impact of current society, which was the primary cause of human misery.” Michael Newman argues that Fourier’s utopian commune, Harmony, had more ideologically in common with the communes of the 1960s than did Saint-Simon’s philosophies. Fourier’s commune focused more on “feelings, passion, and sexuality” than did earlier communes, or phalanxes, as he called them.[4] Fourier also believed that schools should be community-based; that is, they should have no teachers or students, but should be implemented through a more natural process.[5] Fourier was less interested in wealth disparity and class division than other socialist thinkers.[6] He believed communities should have three classes, including the rich, who would help finance the community as shareholders. However, Fourier believed that there would be no animosity among these class divisions because “their primary cause—poverty—would be absent.” According to Fourier’s socialist philosophy, these three groups would work together and have the same educational system, which would lead to “commonality of language and manners.”[7] In this way, Fourier’s ideas differed from other socialist thinkers’ philosophies, yet he was an important founder of utopian communal thought.

Similar to Fourier, Robert Owen (1771-1858) blamed society for individuals’ ills. More motivated to enact change than his predecessors, Fourier purchased land in Indiana for his commune, New Harmony, where he hoped to experiment with utopianism. Owen criticized the way societies operated, blaming them for promoting “selfish and superstitious ways” in its people. He believed these negative qualities in individuals could be transformed through changes in the ways children were raised, relationships between the sexes, and the organization of work patterns.[8] Owen began to attack the outside system of private property and profit, also a theme common in Jones’ speeches. Michael Newman argues that Owen’s emphasis on nurture rather than nature became an important facet of socialist thought in the years to come.[9] Furthermore, Owen also believed that society needed “drastic reformation,” and that marriage, the church, and private property prevented the establishment of a new society, one based on a new moral order. Integral to this new moral order was a “proper environment” with a “suitable educational program.” Owen also stressed that man’s beliefs and character were “determined for him through his environment and not by him through his personal endeavors alone.”[10] These ideas differ from Fourier’s, as Owen “saw character as plastic and open to creation,” and Fourier “saw it as God-given and liable to discovery.”[11] Owen’s beliefs were closer to Jones’ ideas than Fourier’s, stressing the importance of creating an environment rich with educational programs in which community members could reach their full potential.

Influenced by these socialist thinkers, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto in 1848. In his article “Marxism,” Joshua Muravchik contends that Engels took inspiration from the work of Robert Owen.[12] Engels writes in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific that socialism “in its theoretical form … originally appears ostensibly as a more logical extension of the principles laid down by the great French philosophers of the eighteenth century,”[13] showing the lineage of socialist thought moving through Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Furthermore, Engels argues that these socialist philosophers were “extreme revolutionists.”[14] If indeed influenced by the writings of Marx and Engels, as Jim Jones claimed to be, then it follows that by proxy he took inspiration from these early socialist pioneers, making him a revolutionary and a radical as well.

Definitions

Before a discussion of Jim Jones and his radical political ideology can commence, Marx and Engels’ version of communist thought warrants clarification. The authors of The Communist Manifesto claimed “a specter is haunting Europe—the specter of communism,” and called for similar thinkers to come forth with their ideas.[15] In their manifesto, Marx and Engels argued that class struggles between the “oppressor and the oppressed” have caused major problems in society throughout history.[16] However, they believed that as capitalism grew, the numbers of the impoverished workers would grow and the numbers of the wealthy business owners would shrink. Muravchik posits, “This dynamic would make revolution morally necessary and politically possible.” Marx and Engels predicted an uprising of the working class against the bourgeoisie. The proletariats would win the battle and a classless society would result. This theory did not come to fruition as the middle class expanded and the wealthy remained powerful. Still, the allure of Marxism has persisted to the present.[17]

Jones took Marx and Engel’s radical political ideas and distorted them, promoting them as his self-proclaimed “own brand”: “I shall call myself a Marxist, because no one taught me my brand of Marxism. I read, I listened.”[18] Jones’ declaration indicates that the reverend did not follow Marx and Engels’ ideology exactly. Although concerned with wealth disparity, Jones did not speak of an uprising by the poor, as Marx and Engels did. Instead, Jones took a more defeatist position. He instilled hopelessness in his congregation, claiming there could be no escape from the perceived evils of capitalism in the United States. Therefore, while Jones took inspiration from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ The Communist Manifesto, calling his “brand” of philosophy Marxism, it did not adhere to all of the traditional tenets of communist radical thought or the intentions of the authors’ ideas. In 1972, Jones proclaimed, “Man can evolve. Man can grow up till he can be trusted. That’s what we’re saying. The perfection of man. Christians say it, but they don’t believe. [Karl] Marx said it. He said man is capable of perfection. Christians say, that you must be perfect like God is. Jesus said, be ye perfect, even as… I and the heavenly father are perfect”[19] (Matthew 5:48, “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect”).[20] This quotation indicates that Jones drew inspiration from Marx, incorporating Marxist rhetoric within his sermons.

Jones’ version of Marxism has raised much criticism. John R. Hall, author of Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History, writes, “From the standpoint of Marxists, Jones could best be described as a ‘crude communist’ who had little theoretical understanding of the labor theory of value, class conflict, or a host of other issues that Marxists use as touchstones for their debates and strategies.”[21] Journalist Steve Rose calls Jones an “emotional Marxist,” writing that “Marxism was, for [Jones], a means of polarizing the world into Good and Bad;”[22] that is, capitalists and non-capitalists. Mark Lane, author of The Strongest Poison, remarks, “From my one philosophical and political exchange with Jones, I had concluded that his scholarship in Marxist ideology was so deficient that he might have experienced difficulty in distinguishing between the words of Karl Marx and Groucho Marx.”[23] These assessments of Jones’ understanding of Marxism are critical, showing that Jones did indeed invent his “own brand” of radical political ideology that took inspiration from Marx and Engels but could not be called Marxism in the traditional sense.

Jim Jones’ Political Ideology before Peoples Temple

The Communist Party, an important part of Jones’ life even before the formation of Peoples Temple, influenced his radical beliefs. Jones joined the CPUSA (Communist Party USA) during the McCarthy era,[24] although there is debate over whether he was a “card-carrying member” or not. His wife, Marceline Jones, recalled that at the time of their marriage in 1949, Jim Jones was already a committed communist.[25] Although harassed for their show of support for the radical ideology, the Joneses continued to attend Communist rallies during the peak of the McCarthy era.[26] Historian David Chidester remarks in Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown, “During the McCarthy era of the 1950s, Jones called himself a Maoist but still identified with Stalin and the Soviet Union; [Jones] ‘died a thousand deaths’ when the Rosenbergs were executed, executions he saw as an indictment of the American system, ‘an inhumane system that kills people based on a bunch of scrap paper, just because they had Communist affiliations.’”[27] By the 1950s, Jones already questioned anti-communist sentiments in the United States and made his radical beliefs public. According to Hall, Jones claimed to be “enamored of Stalin” because of the Soviet leader’s stand against the Nazis during the Second World War.[28] This sentiment shows Jones’ support for the Communist Party and its leaders in the post-World War II era.

Early exposure to the Communist Party and radical thinking led Jones to conclusions about capitalism in the United States and the actions he could take to steer his members away from pro-capitalist thought. Chidester writes, “Perceiving socialism as an alternative to vast economic inequities, Jones later recalled that his sense of compassion led him to reject the American system of capitalism. ‘It seemed gross to me that one human being would have so much more than another,’ Jones recounted. ‘I couldn’t come to terms with capitalism in any way.’”[29] In statements written in the late 1970s the Reverend Jones mused, “I decided, how can I demonstrate my Marxism? The thought was ‘infiltrate the church.’ I consciously made a decision to look into that prospect.”[30] John R. Hall explains Jones’ rationale concerning using the church as a vehicle to promote his radical agenda:

Thus came Jim Jones’ first and greatest deception: using the cover of a church to preach that religion was ‘the opiate of the people.’ In the United States, serious discussion of socialism effectively has been excluded from mainstream media, and the subject has become virtually taboo for the population at large. One of Jones’ converts, Tim Carter, explained, ‘Telling people about socialism in America, you’d get 20 people. But as a preacher you could get a large audience.’ In semipublic services in the early 1970s, as a sort of bait to the interested, Jones would allude to deeper truths than those he was presenting, much as gnostics and mystics had done before him. By the mid-1970s, he became more and more explicit about his socialist vision… The deception of using religion to promote socialism dissipated for followers as they came to know their leader more intimately, but the persistence of the church front sustained a public relations façade that legitimated the group within established society and attracted support of politicians and other notables, many of whom might otherwise have steered clear of the socialist messiah.[31]

Therefore, while religious tenets existed within Peoples Temple, Jones planned to push his radical agenda onto his followers even before the formation of the church in the mid-1950s. Posing as a purely Christian church was an ideal hiding place for a radical group such as Peoples Temple. Jones recognized this strategy and actively pursued it.

Radical Ideology of Peoples Temple in Indianapolis

Jones’ radical ideas, present from the start of his career as a preacher, came to the forefront as years passed. Jones recalls, “In the early years I approached Christendom from a communal standpoint with only intermittent mention of my Marxist views. However in later years there was not ever a person who attended my meetings that did not hear me say I was a Communist. And that is what is very strange that all these years I survived without being exposed.”[32] This comment shows that Jones’ Peoples Temple began as an insular, private church in which its members accepted his distortion of Marxism in exchange for the non-secular message many followers came to hear.

Furthermore, Jones used biblical passages to support his communist and socialist message. He often cited from the New Testament, relaying to his followers, “Distribution was made unto every man according as he had need” (Acts 4:35).[33] By using the Bible as support for his radical agenda, Jones convinced the more religious members of Peoples Temple to believe that positive aspects of socialism and communism could find a place within a religious group.

In a sermon most likely given in Indianapolis in 1957 or 1958, Jones already gave praise to communism and its leaders:

In just 40 years’ time, Communism has arisen. It’s a challenge to God’s people. It has its own Bible, dialectic materialism. It has its Messiah, Karl Marx. It has its prophets, the Khrushchevs …you don’t want to write him off. Don’t want to write him off, because certainly he’s a talented man of great ability, and the Soviets are way beyond us in scope, beyond our imagination in scientific development.”[34]

Already Jones was pushing his radical agenda by communicating to Peoples Temple members the greatness of the Communist Party and the advancements the Party had made in the Soviet Union.

Jones continued this sermon by tearing down Jesus in favor of the communists. He claimed Jesus was “out with the drunks, out with the harlots, out in the red light district in the back alley, out…dining with…sinners, because they called him a winebibber and a glutton, didn’t they?” This vitriol most likely referenced Luke 7:34 (“The Son of man is come eating and drinking; and ye say, Behold a gluttonous man, and a winebibber, a friend of publicans and sinners!”)[35] Jones continues, “We are all holier than thou, I tell you, I’ve got as much use for him, why, you know before I’d join some of these outfits, before I’d join some of these Pentecostal outfits, I’d join the Communist Party and say Hail Stalin… I’m so sick of it, I believe a Communist’ll have a better chance of gettin’ through than this so-called pack of wolves that call themselves the Church of God.”[36] This sermon exemplifies Jones’ radical beliefs and shows that he was not keeping his communist ideology hidden but passing his beliefs onto his followers as early as Peoples Temple’s time in Indianapolis.

Peoples Temple’s Political Involvement in California

Jones’ desire for political involvement in society became more apparent after Peoples Temple’s move to California in the 1960s. In one sermon given in 1972, Jones proclaimed, “We say, oh the church shouldn’t have anything to do with government. Oh, yes it should, the government is upon his shoulders. We have to get involved with politics… It’s your duty.”[37] This statement marks a major shift as Jones called on his members to actively pursue political endeavors.

Jones’ call to action was realized in San Francisco, California. Peoples Temple members mobilized in large numbers for liberal candidates, including mayoral candidate George Moscone. This support for a politician was one of the first instances during which the public began to see Peoples Temple not only as a church but as an active political force. Long-standing Peoples Temple members had listened to Jones’ radical ideology and push for political involvement for years, so the shift from isolated church to political activism in the public sphere did not surprise them.[38] Grateful to Jones and his followers for their involvement in the community, Moscone relayed the following to the Reverend:

Your contributions to the spiritual health and well-being of our community have been truly inestimable, and I am heartened by the fact that we can continue to expect such vigorous and creative leadership from the Peoples Temple in the future. By your tireless efforts on behalf of all San Franciscans, you have demonstrated that the unique powers of spiritual energy and civic commitment are virtually boundless, and that our lives would be sadly diminished without your continuing contributions.[39]

After the election of Moscone, which many people have attributed to the help of Peoples Temple members, the congregation began to be recognized on the political scene. During the 1976 political campaign, Jones and an entourage of approximately fifteen bodyguards met with Rosalynn Carter, wife of Democratic Party candidate Jimmy Carter. Jones, “looking more like a country-and-western singer than a minister,” was also present to greet and meet with Walter Mondale when the vice-presidential candidate arrived in San Francisco in 1976.[40] Jones implored his followers to vote for Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern in 1972, stating in a sermon that McGovern was “one of the better ones. I’d say that of all the lesser evil, all of you—you got your right mind—will vote for McGovern at this particular juncture. I don’t like to choose between the lesser of, of devils, or opportunities or alternatives, but it’s realistic.” He continues, “Humpty Dumpty” [Hubert Humphrey] would’ve been a better candidate than “Tricky Dick” [Richard Nixon].[41] Although Jones increased his political involvement, he still had suspicions about the candidates, even the liberal ones.

Jones also increased his public visibility in politics after his appointment to the San Francisco Housing Committee as a member and later as its chair by Moscone.[42] In exchange for this appointment, Moscone utilized members of Peoples Temple, a group of “‘hundreds of people from the church at [Moscone’s] disposal at a moment’s notice, [who were] knocking on doors, packing rallies, papering the entire city with posters and flyers. It was zero-cost, total effectiveness,’” journalist Phil Tracy explains in an interview with Leigh Fondakowski,[43] Peoples Temple members heeded Jones’ call to action, influencing politics in California with their large numbers.

Jones and his followers also became activists for social causes in California. In an article printed in the San Francisco Chronicle September 4, 1970, the author writes of Peoples Temples’ efforts to raise money for the families of policemen killed in the line of duty. Jones proclaimed the following:

We are utterly horrified by this move to murder police all over this nation… It’s high time that we let people know that not everyone who is opposed to the war and for social justice hates policemen… We quit marching long ago. We feel positive activism is the only way to achieve change now. We’ve been threatened by extremists ourselves. But violence like this is utter insanity. It’s time we do something, or else we’re going to esd [end] up with state fascism.[44]

These achievements show that members of Peoples Temple immersed themselves in political and social causes throughout the years. Under Jones’ direction, Temple members believed the church should take an active role in politics. Jones attained his goal of leading political and social involvement by placing himself in the same group as the oppressed, warning listeners of a potential fascist takeover that could result without active political participation.

Jones fretted openly about political and social apathy in the United States. Bob Levering of the San Francisco Bay Guardian wrote in 1977 that Jones “saw signs of apathy in the rise of Nazism in this country and the possible rise of fascism as the economy gets worse.” He reported that Jones saw this indifference as one reason the CIA “got away with giving money to support the despotic regimes in Iran and Chile and why the American criminal justice system punishes poor defendants severely and lets off rich ones.” Levering concludes, “Jim Jones has made his share of enemies for his political stands, but no one accuses him of being a hypocrite.”[45]

Bob Levering accurately described Jones as non-hypocritical, for the Reverend pushed his radical agenda in the arena of social justice, equality, and liberal politics, not just with rhetoric but with action. Ray Steele, staff writer for the Fresno Bee, summed up Peoples Temple’s involvement in California politics in an article titled “Peoples Temple: Service to Fellow Man,” printed September 19, 1976. In the article, Steele writes that in the past year (1975-1976), Peoples Temple’s donations helped keep a medical clinic in San Francisco open that otherwise would have been closed; benefitted research in the areas of cancer, heart disease, and sickle-cell anemia; supported educational broadcasting through KQED; provided cash to families in need, particularly those of slain law enforcement officers; increased the treasuries of groups fighting hunger, constructing schools, and building hospitals; and aided civil rights causes, both financially and through demonstrations. Steele writes, “Jones admits he doesn’t adhere to fundamentalist teachings of the Bible, but is driven by his oft-repeated phrase of serving his fellow man.”[46] Steele recognized Jim Jones and his Peoples Temple’s social action in San Francisco, but also the group’s move away from traditional Christianity, which exemplifies Jones’ push for a more radical agenda than before.

Praised for his community work benefitting minorities and the poor in the late 1970s, Jones won several prestigious awards. These awards included the Fourth Annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Humanitarian Award in 1977.[47] The Reverend was named Humanitarian of the Year by the Los Angeles Herald[48], prompting Jones to call 1976 the “Year of [His] Ascendancy.”[49] Most publicity about Peoples Temple and Jim Jones remained positive from 1972 to 1976, the years during which the group congregated in California. However, this seemingly unending praise shifted as journalists Lester Kinsolving, Phil Tracy, and Marshall Kilduff began to report negative stories expressing concern about Jones’ role in Peoples Temple, particularly as a healer.[50] These condemning articles most likely led to Jones’ retreat from San Francisco politics and spurred his move to Jonestown, Guyana.

Communism and Socialism in Peoples Temple

Jim Jones’ ideology regarding communal living did not begin in Jonestown. Prior to the move to Guyana, Jones and Peoples Temple experimented with collectivist ideas. Journalist Phil Tracy recalls Jones saying that he was “feeding six hundred, seven hundred, eight hundred people a night in shifts! And they had access to things that as individual families these poor people never would have had access to… So I didn’t come into this thing thinking Jones was a freak because he was a collectivist… In fact, I thought he was on to something. The collectivist part worked. I thought that worked… But nonetheless, I came into it with great suspicion.”[51] Tracy’s suspicions proved correct, as he also wrote of Jones’ misappropriation of California State funds given to Peoples Temple for foster care. Jones and the Temple would receive an “average of $5 a night for supper, and Jones was feeding them for fifty-five cents, and the difference went into Peoples Temple’s coffers.”[52] Jones’ statements show how some of his early collectivist ideas worked but that they were already corrupted by the mismanagement of state funds.

After Peoples Temple migrated to Guyana and established the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, better known as Jonestown, Jones pushed his socialist agenda to the forefront. Jones required that his people, from the children to the elderly, be educated about the tenets of socialism. Jones read from Tass, the Soviet news agency, over the loudspeaker system nearly every day, with quizzes to follow. Some of the members of Peoples Temple changed their names to Ché (Guevara), Stalin, and Lenin, “though Jones cautioned them to give their birth names when questioned by reporters,”[53] so as not to reveal how radical the church had become politically. This evolution could have sparked public interest and investigation into Peoples Temple, which Jones feared.

Jones continued his anti-capitalist and pro-communist rhetoric in Jonestown. Speaking to the Jonestown community on February 2nd, 1978 Jones declared,

We would like to look for critical reviews, at one insider’s view of the Communist Party USA. In order for fascism to be avoided, there has to be a strong communist party, a strong socialist movement, and free, independent strong trade union [unions], none of which exist in USA, and that is why to avoid your utter destruction, materially most of you, and murder of the rest, I brought you here to regroup, recoup, rehabilitate and gain strength, and militancy, and a proper education in Marxist-Leninism, which you had never picked up, even though I was avowedly, openly Marxist-Leninist and atheist, you have never picked it up, for the most part, in the United States, except for a handful.[54]

Within the same address, Jones praised the Soviet Union and Cuba for their commitment to communism and pushed for revolution in the “puppet regime” of the United States. “It’s important that we keep our radical history and our radical perspective,” Jones implores. This sermon shows Jones’ radical thoughts during Peoples Temple’s time in Guyana but also harkens back to an earlier time, as Jones speaks of “keep[ing]” the church’s radicalism.[55]

Jones’ commitment to his communist and socialist dream would manifest further in Guyana. Demonstrating his dedication to his radical causes, Jones led his congregation with socialist-themed songs to create unity among his people:

Jones: Take your hand to your neighbor, please. The key of my song been, that all these years I’ve had no dying, and this is my theme. (Organ plays) (Sings) “There’ll be no dying,/ There shall be no dying,/ With socialism our leader,/ There shall be no dying.” (Speaks) Let’s make it so. Take your neighbor’s hand and lift it high. (Sings) “There shall be no dying,/ There shall be no dying,/ Oh, socialism is our leader,/ And there’ll be—”

Congregation: (singing) no dying.

Jones: See, socialism is love. Love is God. God is socialism. Draw close and hug your neighbor close to you… Draw close… Get on board, little children. Get on board. Be good socialists, and we’ll cause the kingdoms of this capitalist world to be no more, and become the kingdoms of God and socialism.[56]

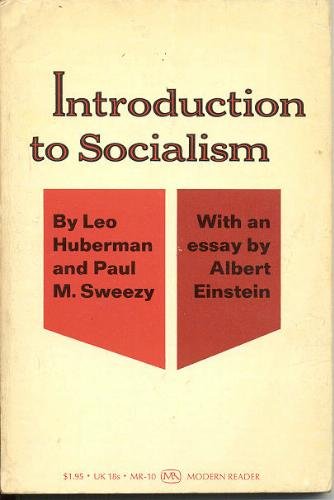

Jones and his people planned to move to the Soviet Union or another Communist nation. By the time the group reached Guyana, prominent Temple members began to meet with representatives from North Korea, Yugoslavia, Cuba, and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union representatives were the most receptive to Jones, and “from youngest to oldest, everyone in Jonestown studied Russian in anticipation of a possible move there.”[57] In a journal entry dated February 3rd, 1978, Jonestown resident Edith Roller recorded, “Socialism classes met at 7:30 – all members of Jonestown are divided into groups for this discussion. Introduction to Socialism by Leo Huberman and Paul M. Sweezy is used as a text. Only the teachers have copies. The classes are so close together with little barrier between them that it is hard for the teachers to make themselves heard.” In her February 1978 journal entries, Roller recalls reading Radicalism in America during her time in Jonestown.[58] These instances indicate the growing radical nature of Peoples Temple. No longer was the Bible the main source of inspiration in the church; instead, books about socialism and radicalism became required reading for Peoples Temple members.

Jones and his people planned to move to the Soviet Union or another Communist nation. By the time the group reached Guyana, prominent Temple members began to meet with representatives from North Korea, Yugoslavia, Cuba, and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union representatives were the most receptive to Jones, and “from youngest to oldest, everyone in Jonestown studied Russian in anticipation of a possible move there.”[57] In a journal entry dated February 3rd, 1978, Jonestown resident Edith Roller recorded, “Socialism classes met at 7:30 – all members of Jonestown are divided into groups for this discussion. Introduction to Socialism by Leo Huberman and Paul M. Sweezy is used as a text. Only the teachers have copies. The classes are so close together with little barrier between them that it is hard for the teachers to make themselves heard.” In her February 1978 journal entries, Roller recalls reading Radicalism in America during her time in Jonestown.[58] These instances indicate the growing radical nature of Peoples Temple. No longer was the Bible the main source of inspiration in the church; instead, books about socialism and radicalism became required reading for Peoples Temple members.

Jones hoped to create a socialist utopian commune that would rival the United States’ capitalist society. “The Jonestown utopia … became a new center, an axis mundi, in the geographical imagination of the Peoples Temple. Jonestown was the new ‘city upon a hill,’ a utopian model for a socialist community that Jones claimed had become the center of attention for the rest of the world,” Chidester explains in Salvation and Suicide. Aware of the attention Jonestown received in the United States, Jones emphasized the importance of his radical commune during his Jonestown community meetings. “‘It’s the only U.S. communist society alive,’” Jones remarked at a rally in 1978. “‘We sure as hell don’t want to let that down.’”[59]

After the move to Jonestown, Jones warned his followers of the potential of danger back in the United States. “[The United States] has always had to have a war or a depression. I tell you, we’re in danger tonight, from a corporate dictatorship. We’re in danger from a great fascist state … and if [we] don’t build a utopian society, build an egalitarian society, we’re going to be in trouble.”[60] These types of statements alarmed loyal Peoples Temple members, who had access only to news Jones relayed to them.[61]

In 1974, Jones spoke of the condition of the United States: “Sure, it’s quiet. But the enemy notices all of that. Who is the enemy? The rich. The love of money is the root of all evil. Capitalism, the oppressive racism, that is your enemy, and they know your every move.”[62] This condemnation of the United States demonstrates Jones’ very vocal and radical anti-capitalist beliefs years before the end of Jonestown in 1978, placing himself and Peoples Temple members in an “us versus them” state.

Jones began to proclaim not only his own socialist tendencies, but those of his people, condemning non-believers. “I’m so purely socialistic and some of my family is so purely socialistic, some of the members of this glorious Temple are so purely socialistic, that you’d be glad to work to see that everyone had the same kind of house, the same kind of cars… People are so afraid of socialism. They’re so terrified. They say, ‘What’ll it do to us?’ Why, you poor people.”[63] This musing shows Jones believed his congregation had shifted from a purely religious group to one focused on pursuing the socialist dream and that those who were not socialists were to be pitied.

However, Jones’ socialist dream was never fully realized. Although Jones claimed equality among his people, later reports stated Jones and the church took money from Peoples Temple members. Guyanese soldiers allegedly found approximately one half-million dollars in cash and envelopes filled with Social Security checks signed over to the church. The author of an article in the November 21, 1978 edition of the San Francisco Examiner also states:

In addition, there was a report that another half-million dollars in gold was found at the camp. Ex-temple members put the church’s assets much higher, however, with some estimates ranging as high as $10 million… While Jones and the church grew wealthy, the members of his congregation were virtually poverty-stricken, ex-cultists have reported. Casual visitors to temple services were asked to contribute what they could to the church’s humanitarian works, full-fledged members living outside the church were required to pledge 25 percent of their earnings to the temple and church commune members were pressured into giving all their income and often property to the church. Pleas for money never stopped.[64]

Therefore, although Jones claimed to be living the “socialist dream,” wealth disparity did exist between Temple members and Jones. Nevertheless, Jones provided for his followers with schools, hospitals, and other facilities to make Peoples Temple members’ time in Guyana habitable.

However, this utopian dream ended abruptly on November 18, 1978. After Jones called for the murder-suicides of Peoples Temple members that day, only one dissenter can be heard on the final audiotape. The dissenter was sixty-year-old Christine Miller, an African American woman whom had been a Peoples Temple member for many years. She asked Jones if it was “too late for Russia,” referring to an earlier plan to move to the Communist nation. Jones responded that Russia would no longer accept the group because after the deaths of Congressman Leo Ryan and his entourage at the hands of the Peoples Temple members earlier that day, the group would be stigmatized.[65] “I feel like as long as there’s life, there’s hope. That’s my faith,” Miller can be heard saying on the infamous “Death Tape” recorded the last day of Jonestown’s existence. She claimed to be unafraid of death, yet said, “But I look at the babies and I think they deserve to live, you know? When we destroy ourselves, we’re defeated. We let them, the enemies, defeat us.”[66] Her ideas were shouted down by Jones and members of the Temple. Despite her protests, Christine Miller died in Jonestown with over nine hundred others on November 18, 1978.[67]

Loyal to Jones until the end, one of Jones’ nurses, Jonestown scholar and historian Rebecca Moore’s sister Annie Moore, wrote in a diary entry that Jones was “‘the most honest, loving, caring concerned person whom I ever met and knew.’” She continues,

What a beautiful place this was. The children loved the jungle, learned about animals and plants. There were no cars to run over them; no child-molesters to molest them; nobody to hurt them. They were the freest, most intelligent children I have ever known. Seniors had dignity. They had whatever they wanted—a plot of land for a garden. Seniors were treated with respect—something they never had in the United States. A rare few were sick, and when they were, they were given the best medical care.

At the bottom of the page, written in a different color, Annie Moore penned, “We died because you would not let us live in peace.” Rebecca Moore speculates that this journal entry was written November 18th, 1978 during the suicides.[68] This sentiment shows the support Peoples Temple members still showed for Jones in their final days. Many followers still believed in the socialist utopian dream in Jonestown and would die for the cause. Most died by cyanide poisoning. Only Jones and Annie Moore would die from gunshot wounds to the head.[69] While Moore’s wound was undoubtedly self-inflicted, there was no definitive determination on whether Jones killed himself or whether someone else fired the fatal shot.

According to historian Rebecca Moore, in a final move to show his commitment to the Communist Party, Jones left everything to the organization in his will, dated October 1977.[70] A conflicting report printed in the San Francisco Examiner on February 8, 1979 states that Jones’ will, dated August 6, 1977, left his estate to his wife, Marceline Jones, and five of his seven children. In the event of the entire Jones family’s death, the Reverend’s assets would be left to the Communist Party. Because his two daughters were left out of the will and three of his five sons survived the massacre at Jonestown, Jones’ money and properties were not given to the CPUSA.[71] Still, the inclusion of the Communist Party in Jones’ will shows his commitment to the cause even after his death.

Political Aftermath

After the deaths of over nine hundred members of Peoples Temple, including Jones himself, politicians expressed conflicting viewpoints about their associations with the Reverend. In an opinion piece in an edition of the San Francisco Examiner dated November 22, 1978, four days after the murder-suicides in Guyana, an article was headlined “Jones and the Politicians.” The unnamed author of the article writes, “At least George Moscone [the mayor of San Francisco] is willing to admit he made a mistake in sizing up the charismatic leader of the Peoples Temple, and appointing Jim Jones to head the city Housing Authority.” However, continues the reporter, some would never go back on their associations with Jones because the Reverend did good works for the community. “A few of these politicians will fashion for themselves a platform of sanctimony high in the ozone of ultraliberalism and maintain that until the Judgment Day that Jones really was a lovely and ‘sensitive’ fellow when they knew him (and got his political support).”[72]

In the same article, Assemblyman Willie Brown of San Francisco continued to show his support for Jim Jones. Brown said on November 22, 1978 that he had “‘no regrets’” about his “‘past associations’” with Jones. “The truth is,” writes the author of the opinion article, “that [Jones] had become liberal chic [in San Francisco] and was embraced by people who wanted his support and didn’t ask enough questions. We hope this will be a lesson to our leaders not to cater to whatever flaky group comes along, in an effort to capitalize off it politically. In the meantime, a little remorse is in order from some parties.”[73]

Jesse Jackson maintained a positive view of Jones, arguing that Reverend Jones was a man who “‘worked for the people’” and that he would defend Jones “‘until all the facts [were] in.’” Jackson stated, “[Jones] felt great concern for the locked out, for the despaired, for the handicapped, for the minorities … and that impressed me. As a result of that, he attracted a great following, and I would hope that all of the good he did will not be discounted because of this tremendous tragedy.’”[74]

These articles show that in the days following the death of Peoples Temple’s members, confusion and ambivalence surrounded the event. Politicians and prominent community members were unsure of how to react to the tragedy. While some stood by Jones, others condemned his actions at Jonestown. Nevertheless, Jones and Peoples Temple’s political impact in Indianapolis and San Francisco did not go unrecognized.

Conclusion and Analysis

The Reverend Jim Jones, a radical before the foundation of his church in the mid-1950s, claimed to purposefully infuse Peoples Temple with his unorthodox beliefs. His ideology included support for communism, Marxism, and socialism in an environment that did not condone such beliefs, as exemplified through the anti-communist McCarthyism of the 1950s. Jones did not hide his radical practices, attending Communist Party meetings and preaching subversive, anti-capitalist messages to his congregation. Radicalism within Peoples Temple intensified as religious messages were pushed aside in favor of Jones’ increasing calls to political and social action in Indiana and California. Jones amplified his anti-capitalist rhetoric and transformed his once more traditional Pentecostal church into a socialist utopian commune: Jonestown, located in the isolated jungles of Guyana.

Jim Jones was not the first to attempt a utopian experiment. Eighteenth-century socialist philosophers, including Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen, indicate a lineage of socialist and communal thought that has persisted for centuries. Fourier and Owen created socialist utopias – the communities of Harmony and New Harmony, respectively – in the United States. Fourier and Owen’s communal experiments ultimately proved unsuccessful, but did not end in the self-destructive, violent manner of the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project in Jonestown.

Marxism, a major part of Jones’ rhetoric, particularly in the later years of Peoples Temple’s existence, perverted the authors of The Communist Manifesto’s original intent. Jones prepared his “own brand” of Marxism, which he relayed to his followers. Jones purported to be operating a religious group rather than a radical counterculture movement. The latter more accurately describes Peoples Temple, particularly in its later years. This strategy proved mostly effective in the 1950s during the McCarthy era in the United States as communists were persecuted and outcast from society. Until the last day of Peoples Temples’ existence on November 18th, 1978, Jones maintained his Marxist viewpoint and commitment to the communist cause.

Jones exercised his liberal radicalism in San Francisco, mobilizing his Peoples Temple to aid Democratic candidates during the early to mid-1970s. He served on committees to benefit the underclass of American society and was rewarded with appointments to community boards and meetings with high-profile Democrats. The time spent in San Francisco indicates Jones’ move toward more public involvement in politics, with which he strongly believed the church had a responsibility to be involved.

After the move to Guyana and the establishment of Jonestown, Jones increased his anti-capitalist and pro-communist and socialist rhetoric. No longer did Jones believe he and his Peoples Temple could enact political or social change within the United States. For Jones and his people, the migration to a newly created socialist commune in the isolated nation of Guyana became the only solution to escape the perceived evils of the United States. This commune would become the site of over nine hundred deaths as Jones convinced his followers they were protesting the inhumane capitalist system that existed in the United States.

The death of Peoples Temple caused much confusion as politicians, clergymen, news reporters, and others grappled with the meaning of the tragedy. Some condemned Jones while others continued to recognize his positive work within the community, particularly in San Francisco. Jim Jones has remained a controversial political figure. While he strove to improve life for minorities and other oppressed groups, he also destroyed his utopian socialist dream in Guyana though the mass murder and suicides of Peoples Temple members. Still, Jones’ radical beliefs and actions persisted until his last day, as indicated by his call for “revolutionary suicide,” enacted November 18, 1978 in Jonestown.

Bibliography

American Experience. “Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple: The Complete Transcript.” PBS.org. Accessed March 15, 2015. https://www-tc.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/media/pdf/transcript/Jonestown_transcript.pdf.

“Anti-War Church Tries Another Way.” San Francisco Chronicle. September 4, 1970. MS 4125, Box 1, Folder 2. California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

Carmony, Donald F. and Josephine M. Elliott. “New Harmony, Indiana: Robert Owen’s Seedbed for Utopia.” Indiana Magazine of History 76, no. 3 (September 1980): 161-261.

Chidester, David. Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Indianapolis, IN: University of Indiana Press, 2003.

Engels, Friedrich. Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Translated by Edward Averling. 1880. Reprint, New York, NY: International Publishers, 2004.

Fondakowski, Leigh. Stories from Jonestown. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minneapolis Press, 2013.

Fried, Albert, ed. Socialism in America: From the Shakers to the Third International, A Documentary History. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1970.

Hall, John R. Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2004.

“Jesse Jackson Stands by Jones.” San Francisco Examiner. November 21, 1978, p. 3. MS 4125, Oversize Box 1. California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

Jones, Jim. “Jim’s Commentary about Himself, 1977-1978.” The Jonestown Institute. Accessed May 16, 2015. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/JJAutobio1.pdf.

“Jones’ Last Will: Estate to Wife, 5 of 7 Children.” San Francisco Examiner. February 8, 1979, front page. MS 4125, Oversize Box 1. California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

“Jones and the Politicians.” San Francisco Examiner. November 22, 1978, p. 30. MS 4125, Oversize Box 1. California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

The Jonestown Institute. “Q134 Transcript.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Accessed May 18, 2015. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27339.

The Jonestown Institute. “Q162 Transcript.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Accessed May 18, 2015. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27350.

The Jonestown Institute. “Q235 Transcript.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Accessed June 14, 2015. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27388.

The Jonestown Institute. “Q929 Transcript.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Accessed May 18, 2015. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27617.

The Jonestown Institute. “Q932 Transcript.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Accessed May 18, 2015. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27618.

The Jonestown Institute. “Q1058-2 Transcript.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Accessed June 4, 2015. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28034.

The Jonestown Institute. “Q1058-3 Transcript.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Accessed May 25, 2015. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27330.

Lane, Mark. The Strongest Poison. New York, NY: Hawthorn Books, 1980.

Leopold, David. “Education and Utopia: Robert Owen and Charles Fourier.” Oxford Review of Education 37, no. 5 (October 2011): 619-635. Accessed July 15, 2015. http://web.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=e4abf5c9-d930-4121-8906-2dbf596cc8de%40sessionmgr4005&vid=1&hid=4201.

Maaga, Mary McCormick. Hearing the Voices of Jonestown. New York, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1998.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto. Translated by Samuel Moore. 1848. Reprint, New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1964.

Moore, Rebecca. A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in the Peoples Temple. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1985.

Moore, Rebecca. Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2009.

Muravchik, Joshua. “Marxism.” Foreign Policy, no. 133 (November-December 2002): 36-38.

Newman, Michael. Socialism: A Very Short Introduction. New York, NY: University of Oxford Press, 2005.

“Peoples Temple Endorsement Packets.” The Jonestown Institute. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Accessed July 9, 2015. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=18355.

Reiterman, Tim and John Jacobs. Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People. New York, NY: Penguin Group, 1982.

“Rev. King Awards Given at Glide.” San Francisco Chronicle. January 17, 1977. MS 4125, Box 1, Folder 3. California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

Roller, Edith. “February 1978 Journals.” The Jonestown Institute. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Accessed June 3, 2015. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35693.

Rose, Steve. Jesus and Jim Jones. New York, NY: The Pilgrim Press, 1979.

Steele, Ray. “Peoples Temple: Service to Fellow Man.” Fresno Bee. September 19, 1976. MS 4125, Box 1, Folder 2. California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

“Temple’s Riches Found at Death Site.” San Francisco Examiner. November 21, 1978, front page. MS 4125, Oversize Box 1. California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

Tyler, Alice Felt. Freedom’s Ferment: Phases of American Social History to 1860. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1944.

Notes

[1] Michael Newman, Socialism: A Very Short Introduction (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005), 6-7.

[2] Newman, Socialism, 7.

[3] Friedrich Engels, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, trans. by Edward Averling (1880; repr., New York, NY: International Publishers, 2004), 31.

[4] Newman, 10.

[5] David Leopold, “Education and Utopia: Robert Owen and Charles Fourier,” Oxford Review of Education 37, no. 5 (October 2011): 619, accessed July 15, 2015, http://web.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=e4abf5c9-d930-4121-8906-2dbf596cc8de%40sessionmgr4005&vid=1&hid=4201.

[6] Newman, 10.

[7] Leopold, “Education and Utopia: Robert Owen and Charles Fourier,” 628-629.

[8] Newman, 10-11.

[9] Newman, 14.

[10] Donald F. Carmony and Josephine M. Elliott, “New Harmony, Indiana: Robert Owen’s Seedbed for Utopia,” Indiana Magazine of History, Vol. 76, No. 3 (September 1980): 163.

[11] Leopold, 619.

[12] Joshua Muravchik, “Marxism,” Foreign Policy no. 133 (November-December 2002): 36.

[13] Engels, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, 38.

[14] Engels, 38.

[15] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto, trans. by Samuel Moore, (1848; repr., New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1964).

[16] Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto, 57-58.

[17] Muravchik, 36-37.

[18] Quote in John R. Hall, Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2004), 26.

[19] The Jonestown Institute, “Transcript Q932,” accessed May 18, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27618.

[20] King James Version.

[21] Hall, Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History, 26.

[22] Steve Rose, Jesus and Jim Jones (New York, NY: The Pilgrim Press, 1979), 62.

[23] Mark Lane, The Strongest Poison (New York, NY: Hawthorn Books, 1980), 106.

[24] Rebecca Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2009), 20.

[25] David Chidester, Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple and Jonestown (Indianapolis, IN: University of Indiana Press, 2003), 4.

[26] Hall, 17.

[27] Chidester, Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown, 4-5.

[28] Hall, 13.

[29] Chidester, 4.

[30] Jim Jones, “Jim’s Commentary about Himself, 1977-1978,” The Jonestown Institute, accessed May 16, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/JJAutobio1.pdf.

[31] Hall, 144-145.

[32] Jones, “Jim’s Commentary about Himself.”

[33] King James Bible.

[34] The Jonestown Institute, “Q1058-2 Transcript,” accessed June 4, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28034.

[35] King James Bible.

[36] The Jonestown Institute, “Q1058-2 Transcript.”

[37] The Jonestown Institute, “Q932 Transcript,” accessed May 18, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=63023.

[38] Moore, Understanding, 29-30.

[39] “Peoples Temple Endorsements Packet,” The Jonestown Institute, accessed July 9, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=18355.

[40] Tim Reiterman and John Jacobs, Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People (New York, NY: Penguin Group, 1982), 302-303.

[41] The Jonestown Institute, “Q932 Transcript.”

[42] Moore, Understanding, 30.

[43] Leigh Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 111.

[44] “Anti-War Church Tries Another Way,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 4, 1970, MS 4125, Box 1, Folder 2, California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

[45] Bob Levering, “Peoples Temple: Where Activist Politics Meets Old-Fashioned Charity,” San Francisco Bay Guardian, March 31, 1977, MS 4125, Box 1, Folder 3, California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

[46] Ray Steele, “Peoples Temple: Service to Fellow Man,” The Fresno Bee, September 19, 1976, MS 4125, Box 1, Folder 2, California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

[47] “Rev. King Awards Given at Glide,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 17, 1977, MS 4125, Box 1, Folder 3, California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

[48] Chidester, 8.

[49] Fondakowski, Stories from Jonestown, 117.

[50] Fondakowski, 117.

[51] Fondakowski, 108-109.

[52] Fondakowski, 109.

[53] Moore, Understanding, 54.

[54] The Jonestown Institute, “Q235 Transcript,” accessed June 14, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27388.

[55] The Jonestown Institute, “Q235 Transcript.”

[56] The Jonestown Institute, “Q932 Transcript,” accessed May 18, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27618.

[57] Moore, Understanding, 54-55.

[58] Edith Roller, “February 1978 Journals,” The Jonestown Institute, accessed June 3, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35693.

[59] Chidester, 96-97.

[60] The Jonestown Institute, “Q162 Transcript,” accessed May 18, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27350.

[61] American Experience, “Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple: The Complete Transcript,” PBS.org, accessed March 15, 2015. https://www-tc.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/media/pdf/transcript/Jonestown_transcript.pdf.

[62] The Jonestown Institute, “Q1058-3 Transcript,” accessed May 25, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27330.

[63] The Jonestown Institute, “Q134 Transcript,” accessed May 18, 2015, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27339.

[64] “Temple’s Riches Found at Death Site,” San Francisco Examiner, November 21, 1978, front page, MS 4125, Oversize Box 1, California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

[65] Moore, Understanding, 95.

[66] Quoted in Moore, Understanding, 96.

[67] Reiterman and Jacobs, Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People, 571.

[68] Rebecca Moore, A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in Peoples Temple (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1985), 336-338.

[69] Mary McCormick Maaga, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown (New York, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1998), 6.

[70] Moore, Understanding, 20.

[71] “Jones’ Last Will: Estate to Wife, 5 of 7 Children,” San Francisco Examiner, February 8, 1979, front page, MS 4125, Oversize Box 1, California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

[72] “Jones and the Politicians,” San Francisco Examiner, November 22, 1978, MS 4125, Oversize Box 1, California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.

[73] “Jones and the Politicians,” San Francisco Examiner.

[74] “Jesse Jackson Stands by Jones,” San Francisco Examiner, November 21, 1978, p. 3, MS 4125, Oversize Box 1, California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA.