The Bit Theater Group in Iran was created to present experimental theater with the aim of better communicating with today’s theater audience. With that in mind, it is necessary to consider the empirical approaches in reviewing the play 1978 and understanding its experimental style.

The Bit Theater Group in Iran was created to present experimental theater with the aim of better communicating with today’s theater audience. With that in mind, it is necessary to consider the empirical approaches in reviewing the play 1978 and understanding its experimental style.

“How does one read a work?” This is a question that a literary critic asks in reviewing novels and collections of fiction, but it is not a simple one. This stems from the differing roles of the participants in the exchange: The author who writes for reading, and the critic who considers the question “How should you read?” In this framework and in accordance with the principle of “reading,” the duty of both sides becomes clear.

But this work is not exclusive to professional readers. The reader of any serious work will be faced with the question “How do I read this?” In that way, the general reader joins those who act as critics and interpreters to make up the book’s “audience.”

So what exists between these two roles, these two functions, the differences between the writer and the audience? A “writing” is the set of words and sentences that shape the narrative. The reader views the author’s sentences one after the other on the page, in order to create a narrative in his own mind. In the face of every sentence or part of the narrative, every reader asks unconsciously, ” How do I read this? How do I add this sentence to the previous and next sentence?” This is truly how the narrative is formed, as the result of the present audience’s involvement with the author’s sentences.

But if we want to generalize the issue of “How do I see this?” with this simple communication model to the theater, we will face the problem. A theater audience, either as critics or as simple and bored collection of theater-goers, is not confronted with a set of sentences and words. The reader closes the book and drinks tea and narrates the sequence of narration to another occasion, but “theatrical narrative” imposes itself on the audience. In theater, that simple communication model turns into a set of sounds, images, sentences and movements that are parallel to real time. Theatrical narrative is complex: on the one hand, there is the collective experience of the audience; and on the other is the work of a group of performers. However, the main question is the same: “How do I see this?” With each component of the narrative, the audience unconsciously asks itself, how can this music be attached to the gesture of that actor, how does that light govern that scene to form the narrative?

In considering the play 1978 then, we must also raise that question: “How do I see this?” It may even be necessary to put the question more precisely: “How do you see this theater?” Each artist is influenced consciously or unconsciously by other arts, common aesthetics, the spirit of time, political, social, cultural, and personal sensitivities in choosing what kind of subject matter, style, and manner to present. These choices do not take place in a vacuum and can reflect the concerns, sensitivities, psychological reactions, psychological reactions, fears and hopes, for individuals, groups and societies.

In considering the play 1978 then, we must also raise that question: “How do I see this?” It may even be necessary to put the question more precisely: “How do you see this theater?” Each artist is influenced consciously or unconsciously by other arts, common aesthetics, the spirit of time, political, social, cultural, and personal sensitivities in choosing what kind of subject matter, style, and manner to present. These choices do not take place in a vacuum and can reflect the concerns, sensitivities, psychological reactions, psychological reactions, fears and hopes, for individuals, groups and societies.

Among the dramatic works of recent years in Iran, these choices are mostly relative. It is hard to understand what the artist’s position is against the subject in these works: artworks exactly depend on what kind of style or even the kind of arts. Because it has a bit of painting, a little bit of a picture, a little dance – a little bit of something from everything – its style is truly a blend of other styles. This is a tendency that is not limited to a few people at any given moment, or even to one generation. It is a pervasive phenomenon. The prevalence of such an approach can be sought in the space and place of artists’ lives. Today’s life in Iran, probably as elsewhere, is an unbreakable combination of the most disparate elements possible in the public and private spheres of life and citizenship. What art can be pure in such a situation where the fragmented identities has gone through our existence? Which language can be definite and pure?

In Iran, where difficult political and social conditions were barred from being explicitly expressed, absolute concepts have been questioned widely over the past few years. Although we still face boundaries in official art space – and in terms of subject matter, ideological position, political stance and moralism, those boundaries are decisive – there are many works that have been interstitial and made their own world. Ambiguities, contradictions, multiple disciplines, and introspection show themselves more than ever in these works and thus constitute an important part of contemporary Iranian art.

In Iran, where difficult political and social conditions were barred from being explicitly expressed, absolute concepts have been questioned widely over the past few years. Although we still face boundaries in official art space – and in terms of subject matter, ideological position, political stance and moralism, those boundaries are decisive – there are many works that have been interstitial and made their own world. Ambiguities, contradictions, multiple disciplines, and introspection show themselves more than ever in these works and thus constitute an important part of contemporary Iranian art.

Although some people call this interstitial approach opportunist, without a message and supported only by anecdotal evidence, the fundamental question of the creators of the new artwork is whether the fear of disparity should be tied to the fictitious order and the existing queues.

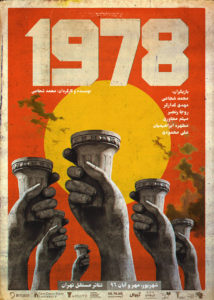

Let’s go back to the question, “How do you see the theater?” What’s seen in 1978 is a concise narrative of the story of Jim Jones’ life and death, and death of members of Peoples Temple. It is a documentary drama based on one of the major events in modern human history. Although this show does not remain loyal to the narrative of the underlying event, the story of the leader and members of the Temple is still a driving engine: that is, the principles of the story are intact. The storyline is more or less the same, with a beginning, middle, and end of the history of Jim Jones and the evolutionary path he took as a charismatic leader through his death – and those of his followers – on November 18, 1978.

But this storyline is only a small part of the narrative. If we want to understand it, we need to look at other parts with care. The narrative in this show includes events, characters, nonlinear time, uncertain location and all the theatrical expression techniques from dialogue to gesture. This complex network creates a landscape in which everything else is not explicitly non-experimental: time breaks; the places get lost; and sentences and words turn into voices and sounds. This creates a new experience in narration, an experience in which the story line is preserved only to order all the elements in the circle.

The narrative of 1978 is sometimes presented in the form of words and sometimes in the form of motions, but the only instruction is to watch and see how the narrative is not presented. If we consider the behavior and motivations and sentences of some characters as criteria, then what is our assignment with the rest of the different events? How do we track them? Are there any stories behind the geometric mise-en-scène of the cast or their group singing? Is the audience at the time of Jim Jones’ growing influence, looking for an omen and a reference to the environment and the period in which the individual lives? If the answer is yes, then why are not all the questions answered the same way?

The narrative of 1978 is sometimes presented in the form of words and sometimes in the form of motions, but the only instruction is to watch and see how the narrative is not presented. If we consider the behavior and motivations and sentences of some characters as criteria, then what is our assignment with the rest of the different events? How do we track them? Are there any stories behind the geometric mise-en-scène of the cast or their group singing? Is the audience at the time of Jim Jones’ growing influence, looking for an omen and a reference to the environment and the period in which the individual lives? If the answer is yes, then why are not all the questions answered the same way?

The action taken by the audience in passing through this hollow space is the same that contemporary art seeks to achieve. Only in that way can the drama accomplish its goal to go beyond any style and method based on our time, our society and our identity.

(Mohammad Shojaei is the writer and director of 1978. He can be reached at mohamad.shojaei@gmail.com.)