The notorious Charlottesville, Virginia protests defending statues of Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, the ensuing violence that took the life of counter-protestor Heather Heyer, and the President’s equivocating remarks about it, led more than 30 cities across the United States – including Los Angeles, San Diego, Brooklyn, and Austin – and locations in every region of the country, to remove or relocate Confederate statues and tributes that were installed in the 20th Century. Along those lines, the San Francisco Arts Commission voted unanimously in September to dismantle and remove the Early Days statue from the city’s Civic Center Plaza finally regarding it as a “racist and disrespectful sculpture,” because it valorized the European and Christian conquest of Northern California Native Americans who opposed it. A crowd of fifty people from the indigenous communities were on hand to observe the removal.

This is not the only such action in the works:

- The San Francisco Board of Supervisors is considering changing the name of San Francisco International Airport to the Harvey Milk International Airport, a fitting tribute to a trailblazing leader, activist, and city official whose political and ideological orientation and fate in November of 1978 will forever be linked to Peoples Temple and Jonestown.

- After two decades of student activism, the University of San Francisco removed the name of former San Francisco Mayor James D. Phelan (1897-1902) from a student residence hall. Phelan once ran an anti-Japanese “Keep California White” campaign and in 1919, while a U.S. Senator wrote the article “The Japanese Evil in California,” which argued that “the Japanese do not belong in California.” The internment of 120,000 Japanese Californians

Burt Toler Residence Hall from “Nihonmachi” (Fillmore/Western Addition) and Los Angeles to internment camps on the West Coast by FDR’s Executive Order two decades later, was one of Phelan’s irredeemable legacies in the City and state, even as history credits him with helping resurrect San Francisco from the ashes of the 1906 earthquake. Fittingly, the university leaders insist, “We cannot scrub Phelan from our history, nor turn away from the complexity of his story.” The dorm at USF will now be known as Burl Toler A. Hall, named after African American football legend at the school in the early 1950s who went on to be inducted in the NFL Hall of Famer as an official. Phelan’s name remains on other sites around the city.

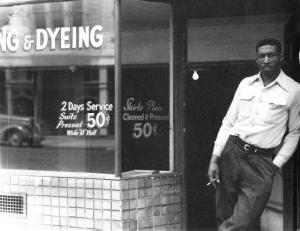

- For as many decades, activists and residents such as the late Rev. Hannibal Williams and Mary Helen Rogers with the Western Addition Community Organization (WACO), as well as the residents whom the community group represents in the Fillmore/Western Addition, have felt the legacy and impact of former Redevelopment Agency head Justin Herman. Deserving of public repudiation, Herman had a leading role in “Negro Removal” from the area to make room for urban development during his tenure from 1959 to 1971, an era that preceded the arrival of Peoples Temple to San Francisco. Former Black Power radical and Temple enforcer Chris Lewis physically attacked Herman publicly days before the official’s fatal heart attack.

KQED’s 1999 documentary on The Fillmore powerfully captured the community’s sentiments towards Herman, as Rev. Williams articulated:

The times were right to produce a man like Jim Jones. The circumstances of a community that is broken up, when the relationships that bind people together fall apart, the time is always right for a religious scoundrel to take advantage of our credibility. Justin Herman literally destroyed the neighborhood and in the process he made the neighborhood ripe for anybody with any kind of solution. People were desperate for solutions, something to follow. Jim Jones was another solution. He had a charismatic personality that won the hearts and souls of people. And people followed him to hell. That’s where Jim Jones went. That’s where he took the people who followed him.

* * * * *

Days after the violence of Charlottesville, the San Francisco Chronicle published an article“A Site without a Name is Invisible,”by African American staff writer Callie Millner, which listed important unmarked sites across the city of San Francisco in relation to the removal of the monuments. In the piece, Millner considers whether

city leaders were willing to consider naming a few places for the very first time… San Francisco is great at noting our tourist attractions and our happy history. But every city does that. San Francisco would be far more remarkable if we noted where our difficult chapters happened, too. When a city commemorates the more difficult chapters of its past, it’s a sign to residents that everyone’s experience is important. It’s also a reminder to every member of the community that we’re all responsible for avoiding the mistakes of the past.

The article highlighted the need for public recognition of the Pilipino struggle around the International Hotel, which represented the removal of the community from the Yerba Buena/Manilatown section forty years ago, and “Peoples Temple/Victims and Survivors of Jonestown.”

Interviewed for an academic perspective, I was asked questions whether the City should dedicate or make tribute in particular to those who perished at Jonestown. I already know how raw and gaping the pain remains for so many still. As an example, in the course of my work on a book project concerning Peoples Temple, I attempted to interview a surviving family member. The only thing she said to me was, “He [Jim Jones] was evil and, I do not talk about it; he was evil.” When I tried a second time to talk to the relative, I was ushered out the door of an Oakland business and the door was locked behind me, even though this was in the middle of the day.

I nevertheless responded to the question, that perhaps there should be a memorial, given the passage of time. I suggested further, that no matter what else, the city of San Francisco also had responsibility that needed to be reconciled, if possible, and an appropriate site might be an important step toward a new chapter in how San Francisco presents itself to the world, the good and horrible, especially as it experiences further declines in the City’s Black, Latinx, and other struggling communities.

* * * * *

Since 2000, both San Francisco and Oakland have experienced a population turnover. The postwar migration to San Francisco of workers drawn in large part by the defense industry ended in 1970, and with the decline of those jobs beginning then, more than 400,000 of those immigrants and their families began to leave. Coupled with that was the influx of more than 300,000 new city residents of a new generation drawn by Silicon Valley. Neither the two previous generations nor the present have benefitted from whatever official public recognitions accomplish in pulling down or erecting tributes to critical parts of history, infamous or not. That includes something about Peoples Temple. At this point, two full generations later, there also seems to be little value in opening debate on the myriad questions implicated in such a memorial, especially – and this may be the most telling one – that Jonestown did not happen in San Francisco (or Indiana, or Ukiah, or Los Angeles, for that matter).

Since 2000, both San Francisco and Oakland have experienced a population turnover. The postwar migration to San Francisco of workers drawn in large part by the defense industry ended in 1970, and with the decline of those jobs beginning then, more than 400,000 of those immigrants and their families began to leave. Coupled with that was the influx of more than 300,000 new city residents of a new generation drawn by Silicon Valley. Neither the two previous generations nor the present have benefitted from whatever official public recognitions accomplish in pulling down or erecting tributes to critical parts of history, infamous or not. That includes something about Peoples Temple. At this point, two full generations later, there also seems to be little value in opening debate on the myriad questions implicated in such a memorial, especially – and this may be the most telling one – that Jonestown did not happen in San Francisco (or Indiana, or Ukiah, or Los Angeles, for that matter).

But we are in that moment. We are in a cultural and political environment in which the city of San Francisco – and the state of California – consider what to do with tributes and statues honoring the Confederacy, especially since the Civil War was not fought on the city’s streets. One could seriously debate whether Memphis should recognize the death of an Atlanta preacher named Martin Luther King – who was assassinated killed within its city limits, but who is buried in his hometown – in the form of a monument. And how does Money, Mississippi mark the death of young Emmitt Till? Or Dallas recognize the blood of John F. Kennedy? Or Harlem, the blood of Malcolm X? Or Jackson, Mississippi, the blood of Medgar Evers? Or Ferguson, Missouri, the blood of Mike Brown? And what of Oklahoma City? What of the Twin Towers in New York? All very different – especially in how well they are known – but what they have in common is that the cities worked through the hate, and the tears, and eventually erected monuments. Even the government of Guyana has a monument to the people of Jonestown.

Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, now a sacred site for the Jonestown dead, was once part of the NIMBYism that ran from Guyana, Washington, DC., and Delaware, to powerful circles in the state and city of San Francisco. The presence of the actual people there – young and old, unidentified and unclaimed – gives them a human recognition and a place that no place in the world gave, thanks to Evergreen, Oakland, the San Francisco religious community’s Guyana Emergency Relief Committee, and in 2011, the Jonestown Memorial Committee.

Standing at Evergreen in East Oakland on several anniversaries since 2006, I’ve looked down at the gravesite as people spoke, preached, grieved, and comforted one another. I’ve looked up and felt the press of both the tragedy of those who died 40 years ago, and the realities surrounding them among the living in the streets of East Oakland. Even as incomprehensible tragedy happened in Jonestown, Peoples Temple arguably had its best life, while in the then-thriving Black Fillmore of San Francisco. Put differently, Peoples Temple died in Jonestown, but it lived in San Francisco, in one of its most vital communities at a critical time in its history. It provides a powerful remembrance and metaphor of the post-World War II life and decline of the community that soon followed the events of Jonestown and the onslaught of “crack,” which was yet another death knell.

More recently, a local Methodist Church in the Fillmore once pastored by Rev. Williams, hosted a small but charged gathering which addressed the rich history of the community as well as its highs and lows, and decline by the early 1980s. I was fortunate to be asked by its organizers of long time community residents and leaders, to share some of my thoughts at this gathering based on years of teaching, research and scholarship in Black politics and writing on the Peoples Temple movement. The article in the San Francisco Chronicle covering the event included my comments discussing the need for the city of San Francisco to finally recognize the Peoples Temple movement as an essential part of the Fillmore community’s and City’s rich history, and the need for pressure to be placed on city leaders for a site that in some small way, makes an offer of recognition and public accountability. I talked about then-Acting Mayor London Breed, who grew up in the community with the stigma of Jonestown overshadowing her youth in the Fillmore and who knew many of the affected families at one of Peoples Temple’s ground zeros. During my presentation, one individual of some importance and longtime residency stood up and angrily interrupted me with his objection to any attempt to place Peoples Temple, Jim Jones and the tragedy at Jonestown within any relationship to the community or its histories, no matter how inseparable, in fact. The reaction rang of the “distancing” that characterized one of many reactions to the movement’s destruction in Guyana.

Earlier this year, I was contacted by a grassroots group of people from the Fillmore, with all but one person—whose grandfather is included in Katheryn Barbour’s Who Died (2014)—having no direct ties to Peoples Temple’s surviving communities and families. Organizing around many of the issues that have been perennial, even those that Jim Jones and Peoples Temple spoke to in their time, the New Community Leadership Foundation (NCLF) formed in order to advocate and fight for the remnant African American community, families, and children and public space in the Fillmore, amid its latest demographic changes. Many of the residents today are immigrants from Eastern Europe (the Japanese and African American declines are well documented in depressing accounts such as the 2016 New York Times article, “The Loneliness of Being Black in San Francisco”). The Millner piece in the San Francisco Chronicle is filled with hope that the city would “do the right thing” about these (un)pleasant histories, but concludes,

the victims of Jonestown were disproportionately San Francisco’s least politically empowered demographic —low-income African American women. Many of the San Francisco leaders who behaved badly during the Jonestown crisis still have far too much power here today. So I don’t anticipate any official commemoration to happen anytime soon.

Partnering with the “San Francisco Beautiful” foundation, the NCLF has obtained a significant monetary grant, that may accompany others, supported by City agencies, to dedicate the Mini Park space for community preservation and use in the Fillmore as the Fillmore Mini Park. From its Jazz age to this day, obscure, unremarkable bricks in the sidewalk of Fillmore Street here and there – if you look really hard for writing on the bricks – can be observed. We hope the winning bid is something more visible and significantly marked than that. On September 4, 2018, The San Francisco Chronicle published a front page article, “Appetite for black success in Fillmore,” which outlines the impact of recent population declines in the City, on black businesses that have closed like Yoshi’s jazz club, Marcus Books, Gussie’s Chicken and Waffles, and 1300 Fillmore. Promoting the opening of a second location in the Fillmore, the owner of Farmersbrown’s insists the key to success with “now basically an almost nonexistent” black community clientele might be in “connecting with the audience that has longed [long] called the Fillmore home, efforts that he believes are missing among other businesses in the area.”

the Fillmore as the Fillmore Mini Park. From its Jazz age to this day, obscure, unremarkable bricks in the sidewalk of Fillmore Street here and there – if you look really hard for writing on the bricks – can be observed. We hope the winning bid is something more visible and significantly marked than that. On September 4, 2018, The San Francisco Chronicle published a front page article, “Appetite for black success in Fillmore,” which outlines the impact of recent population declines in the City, on black businesses that have closed like Yoshi’s jazz club, Marcus Books, Gussie’s Chicken and Waffles, and 1300 Fillmore. Promoting the opening of a second location in the Fillmore, the owner of Farmersbrown’s insists the key to success with “now basically an almost nonexistent” black community clientele might be in “connecting with the audience that has longed [long] called the Fillmore home, efforts that he believes are missing among other businesses in the area.”

On November 18, 2018, the executive leadership of “San Francisco Beautiful” and the NCLF will announce details of a public bid for proposals to dedicate a fitting monument on Fillmore Street next to the McDonald’s, to “The Peoples Temple/Victims and Survivors of Jonestown.” Ideally, the marker would be at the site of Peoples Temple, but it is in the community, on the same street where Peoples Temple once called home, (since the U.S. Postal Service occupies the actual site of the Temple at 1859 Geary). The event theme is “Homecoming: A Day of Atonement in the Fillmore, Reclaiming Heritage in San Francisco.” Its aim is to come full circle with this painful past, to call people back to the Fillmore and San Francisco on this day, to extend and mark a public space in San Francisco, and to place the City of San Francisco on the right side of how Peoples Temple might be preserved and publicly presented as part of the city’s past, no matter how deeply painful, for future generations of visitors, students, new residents, researchers, and leaders to understand.

We regret the scheduling conflicts with the important 40th year observations in Oakland and tried unsuccessfully to accommodate them.

These community-based organizations and their public and private partners recognize the 40thyear since Jonestown and the end of Peoples Temple for the milestone observation that it is for the community, for the City of San Francisco, for any media or remaining public interest, and most particularly for surviving families scattered throughout the country. Weather permitting, participants will walk together, hand in hand, step by step, arm in arm, from 1859 Geary Blvd. at 2:00 pm, following a media press statement, down Fillmore to the Mini Park at Fillmore St., between Turk and Golden Gate. People who are not able or inclined to participate in the walk, can join the program that begins at 2:30 pm and continue to partake of live music, food, prayer and the reclaiming and dedication of space in the Fillmore/Western Addition.

The rise of London Breed in the City’s government and politics evidences how, since the 1850s, Black San Francisco in the Fillmore, at every stage of its history, has outperformed its size, impacting many areas including labor, business, civil rights, black power, government, literacy, educational attainment, law enforcement, Be Bop Jazz, and radical and progressive politics. Black San Francisco’s reach, has always been far greater than its size. Of late, Oscar Grant on BART, Colin Kaepernick and #BlackLivesMatter happened here. Henceforth, the public will be reminded daily, at one time, so was Peoples Temple.

See info@NCLFINC.org or www.NCLFINC.org, or call 415-857-1136 for more information.

(James Lance Taylor, Ph.D is a Professor of Politics and African American Studies in the Masters of Urban and Public Affairs Program at the University of San Francisco. He is also the author of Black Nationalism in the United States: From Malcolm X to Barack Obama (Reinner, 2014) and Peoples Temple, Jim Jones, and California Black Politics (forthcoming). His article on Peoples Temple can be found in “Black Churches, Peoples Temple, and Civil Rights Politics,” in R. Drew Smith (ed), From Every Mountainside: Black Churches and the Broad Terrain of Civil Rights (State University of New York Press, 2014. He can be reached at taylorj@usfca.edu.)