(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May 8, 2016 edition of Kernel Magazine.)

Fielding McGehee knows when Jim Jones is about to repeat himself. “He has verbal cues,” McGehee tells me. “When he gets on one of his toots, I can pretty much type as he’s talking. He’s just playing his own tape.”

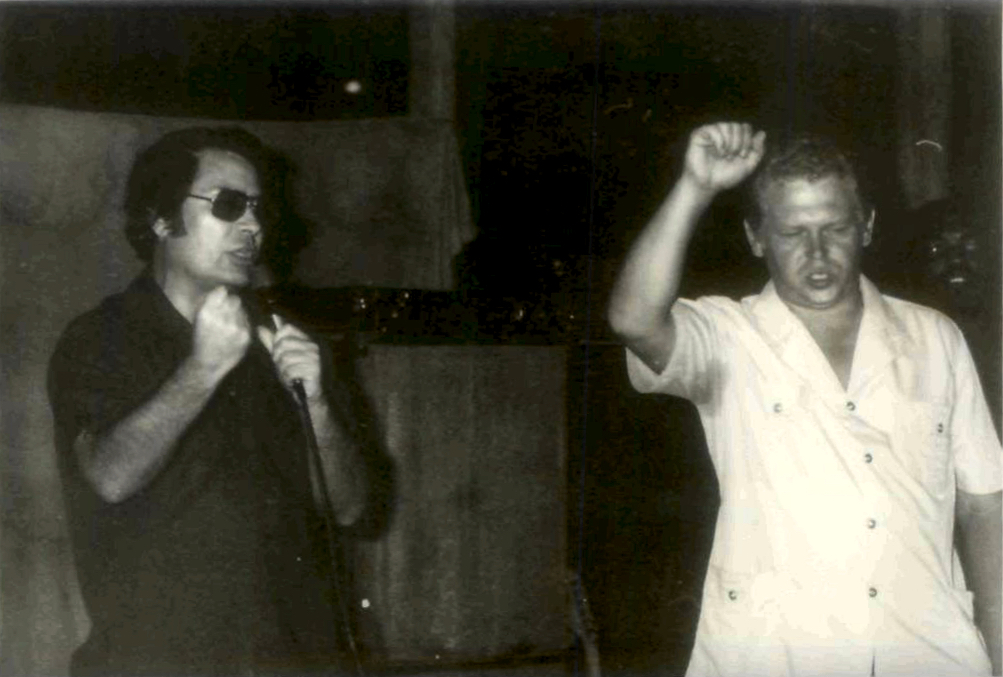

McGehee is familiar with those cues because he’s listened to Jones—the charismatic leader of the Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ, a religious movement made infamous on Nov. 18, 1978, when Jones and more than 900 others died in a mass murder-suicide—more than anyone else alive. McGehee has heard Jones at his most critical, like when he complains that his congregation is failing to follow orders. And at his most paranoid, when Jones describes the American government locking black people in concentration camps. And at his most compassionate, when he tells his followers he loves them—and sounds like he means it.

McGehee is familiar with those cues because he’s listened to Jones—the charismatic leader of the Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ, a religious movement made infamous on Nov. 18, 1978, when Jones and more than 900 others died in a mass murder-suicide—more than anyone else alive. McGehee has heard Jones at his most critical, like when he complains that his congregation is failing to follow orders. And at his most paranoid, when Jones describes the American government locking black people in concentration camps. And at his most compassionate, when he tells his followers he loves them—and sounds like he means it.

Or meant it, that is. Tenses play murkily in the world of archival recordings, where even four decades later, the past is vibrant and alive in the headphones. McGehee spends much of his time in that world, transcribing tapes recovered by the FBI from Jonestown, the commune in the jungles of Guyana where Jones and his followers met their ultimate end.

The tapes exist because Jim Jones was himself an archivist. From the beginnings of the Peoples Temple in 1955 Indianapolis to its height in 1970s San Francisco, Jones recorded his sermons. He wanted both to create a historic document and for them to be passed from one congregation to another, extending the reach of his message. Over time, tapes were recycled; the remaining ones were supposedly burned in a bonfire at Stinson Beach in Marin County, California. But down in Jonestown, the FBI found nearly 1,000 more tapes. They were taken to Washington, D.C. for investigation, but on eventually releasing the tapes to the public, the bureau provided only raw summaries describing what was on them, including the ever-popular description “Jones speaking.”

“Hell, that could be anything!” says McGehee, so he’s been listening and transcribing to discover just what’s on the tapes. Sometimes, it’s nothing. “We’ve found an exciting tape that had one minute of a truck engine running,” he says. “But we also found tapes where Jones talks about the conspiracy against him, how they’re going to take on their enemies, how they’ll fight to the last man.” The tapes are in no particular order, labeled with an arbitrary numbering that’s beautiful in its bureaucratic apathy. Yet when examined, the tapes tell the true story of what happened at Jonestown. “You can hear the deterioration of the community, almost in real time.”

For the 66-year-old McGehee, each new tape is a mystery, and he’s never sure what he’ll find. Unraveling the larger mystery of what happened at Jonestown is what has kept McGehee and his wife, Rebecca Moore, persevering in assembling the definitive archive of the Peoples Temple. They’ve spent four decades listening—and they’re not stopping anytime soon.

“I once said my last day is going to be Nov. 18, 2028, the 50th anniversary,” says McGehee. “But I realize now I may not be done. I’ll keep going as long as I can, but it’s a job that hasn’t been finished.”

McGehee—who previously had a “varied career” as reporter and political activist—recalls exactly where he was when he heard about the tragedy at Jonestown. By then, Jim Jones had already made a mark on his family.

Years earlier, his wife’s two sisters, Carolyn and Annie, had fallen in with the Peoples Temple, both becoming integral members. On the morning of Nov. 19, 1978, as they left their Washington, D.C., home for a jog, McGehee and his wife glanced at the newspaper. They saw that U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan, who’d gone to Jonestown at the behest of his San Francisco Bay Area constituents worried about their relatives living in the commune, had been assassinated by members of the Peoples Temple.

“It didn’t really register,” says McGehee. “About 10 minutes into [the jog], Becky was like, I’m too distracted; let’s go back and figure out what the hell’s going on.” They began making phone calls, following reports, sifting the nuggets of truth from the cloudy deposits of breaking news. Shortly after Ryan’s murder, Jim Jones told his congregation they had only one option: The collective suicide he’d spent months preparing. He told them how their deaths would be viewed, saying, “We committed revolutionary suicide protesting the conditions of an inhumane world.” At least some Temple members protested, but Jones was adamant, raving about the forces arrayed against him and cajoling his flock to follow him by drinking a cyanide-laced fruit drink.

They did—though not as docilely as would be later suggested, and evoked the glib phrase for unthinking allegiance, “drinking the Kool-Aid.” The night was chaotic, and few Temple members survived. In the aftermath, confused reports reached McGehee and his wife at their home. People were dead, they knew, but how many? First it was a few hundred, then 700, now 900. The Moore sisters played a central role in the Peoples Temple and were unlikely to have survived. Later, a letter from Annie Moore arrived, beginning ominously, “I am 24 years of age right now and don’t expect to live through the end of this book.”

They flew to Reno, Nevada, to be with Moore’s parents, and the family debated what to do. Rather than letting the confused reports trickling out of Guyana define their daughters’ lives, the family decided to speak out on behalf of those who couldn’t speak for themselves. Moore’s father, a Methodist minister, used his pulpit to urge the world to see more than bodies at Jonestown—to see them as people.

Within a few weeks, Moore and McGehee filed their first FOIA request with the CIA, seeking any information about Peoples Temple. Initially, they were blown off: A rep asked why they’d believe the agency knew anything. “Give me a break,” McGehee told the rep. “You have 900 Americans who’ve renounced the U.S. very publicly, went to a Third World country with a socialist society, and took millions of dollars with them.” Common sense broke the agency’s poker face. “He said, ‘Well, I guess when you put it that way.’”

Thus began the largest collection of documents relating to Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple. As the CIA and FBI finished their investigation over the next few years, they began releasing documents, essentially straight to McGehee and Moore’s mailbox. McGehee estimates they’ve filed nearly 300 FOIA requests, in addition to multiple lawsuits—one of which remains active—to build the collection they maintain as the Jonestown Institute. It includes census records from the Peoples Temple, sermons, letters, critical writings by concerned relatives, government documents tracking the organization, and yes, all those tapes.

In 1998, they began putting the collection online.

The Web archive of the Jonestown Institute,“Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple,” states that its purpose is to “present information about Peoples Temple as accurately and objectively as possible.” It’s all laid out for anyone to access. Sometimes, the audience is bored college kids looking for some midnight macabre. Other times, it’s researchers closely inspecting Jim Jones’s world. John R. Hall’s Gone From the Promised Land drew heavily from the archive, as did David Chidester’s Salvation and Suicide, the NPR documentary Father Cares, and the PBS documentary Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple.

“I’m suspicious of any resource that claims to have comprehensive information. Usually, it means they just have whatever facts, or apparent facts, to back up whatever the people running it believe,” says Jeff Guinn, an author of nonfiction books covering everything from Charles Manson to Bonnie and Clyde to the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, who’s working on a new book about the Peoples Temple. He’s written that it’s “the toughest project I’ve ever undertaken.” But, he says, “One of the things that astonished me about the Jonestown Institute was the willingness to accept all points of view and simply make them available, even if it might be something they personally disagreed with.

“Working with [them] provided me with invaluable tools—not only the material, but their willingness to get me in touch with other people, even those who disagree vehemently with a lot of the things on the site,” Guinn adds. “They don’t exclude anyone. That’s important.”

Guinn’s book, scheduled for spring 2017 publication, is called Someday Everybody Dies: Jim Jones, Peoples Temple, and Jonestown. The title references a quote by Jones from the so-called “death tape,” recorded as he urged his followers, many of whom resisted until the end, to participate in the mass suicide. It’s easily the most harrowing of all the tapes—and not coincidentally, the most listened-to by far. But getting through just a few minutes of it is tough enough, so how can anyone spend years with this material?

“It’s not a project for the faint of heart,” McGehee says. “It’s hard to say I enjoy the work, but I get real fulfillment out of it.” Decades of work have helped the couple find some distance from the work, but it still affects them. “Becky can always tell when I’ve been working all day on photos of the kids, or working with family members who had children in Jonestown,” says McGehee. It’s an all-encompassing task: time not spent transcribing, or making PDFs searchable, or editing articles, or putting together the annual compendium The Jonestown Report is spent diving back into the archives to make corrections.

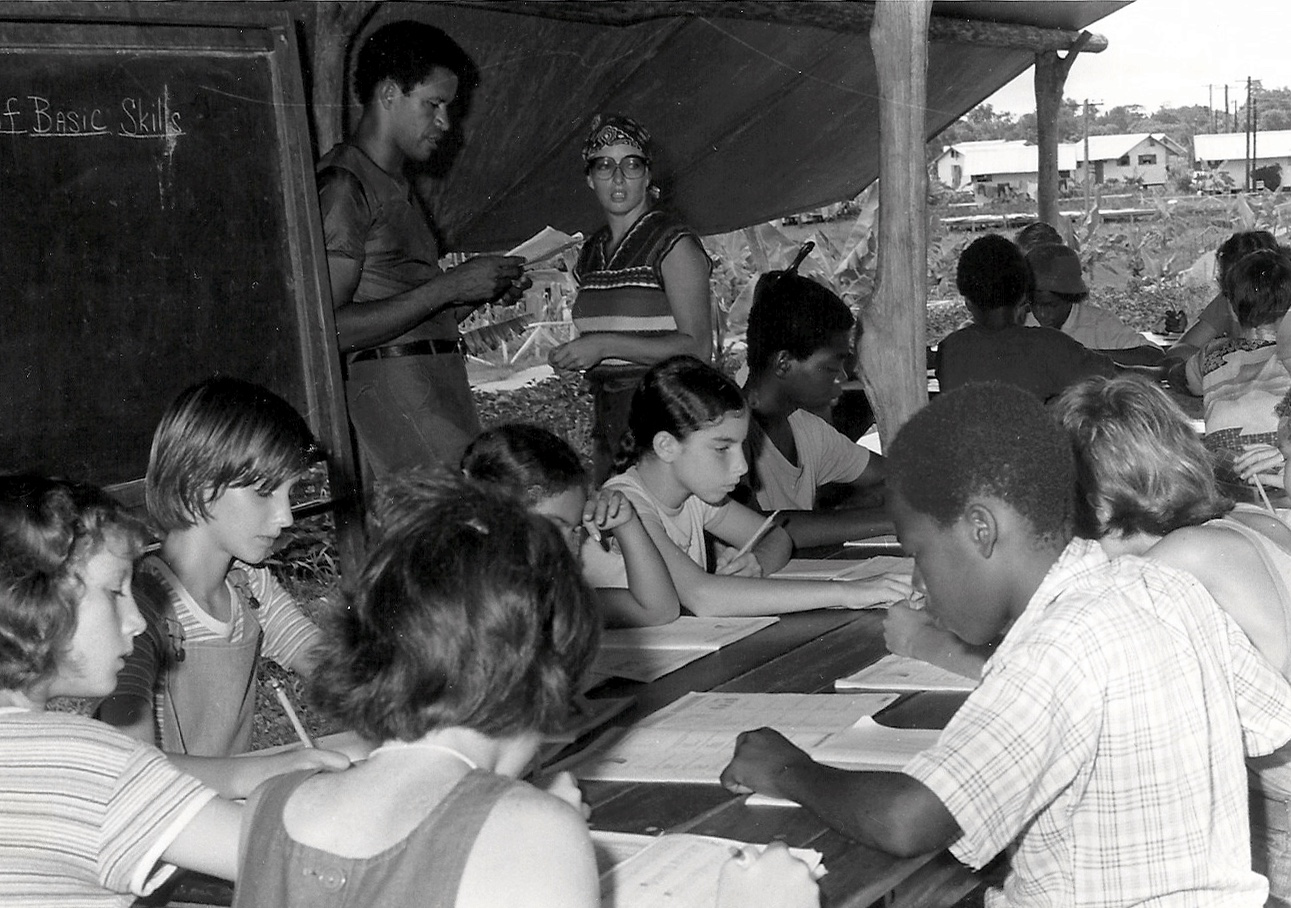

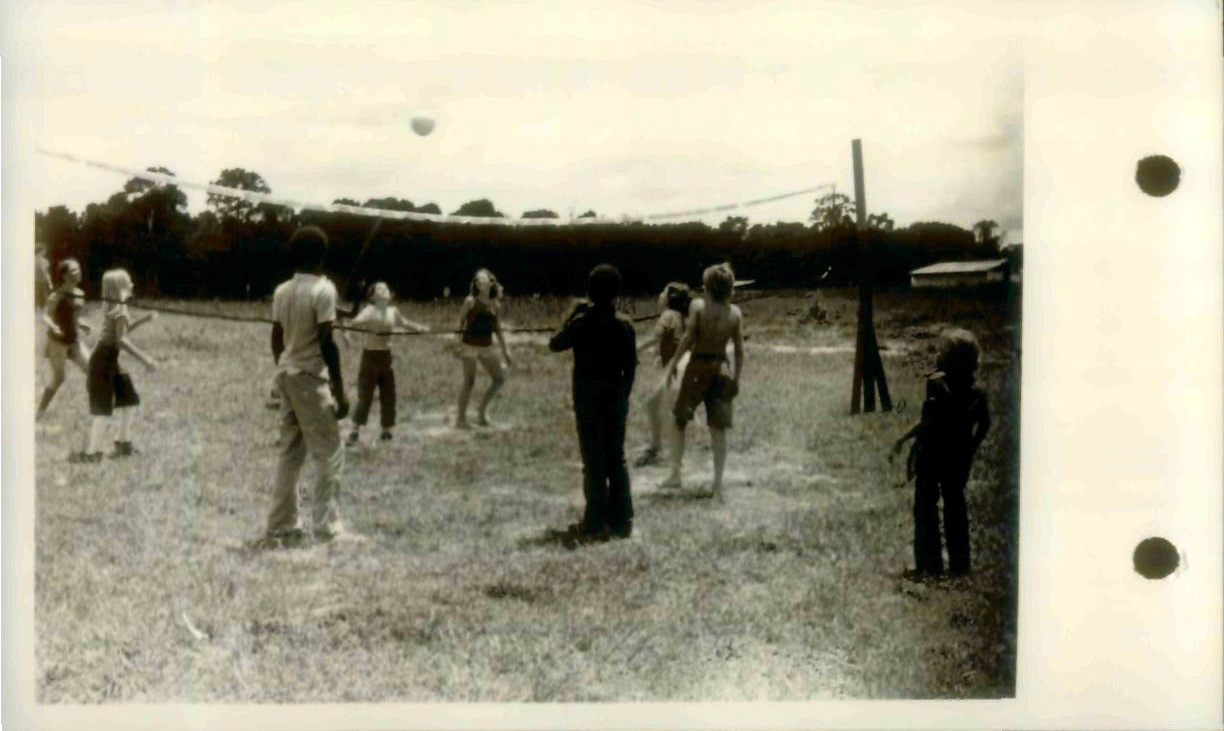

To McGehee, the popular understanding of the Peoples Temple and what happened in Jonestown are as incomplete as 18th-century maps of Africa. “It had shorelines, maybe a couple of major rivers, Mount Kilimanjaro.” With their work on the archive, Moore and McGehee hope to fill in the map and make it actually useful for future explorers—so that anyone who truly wants to study the Temple can find some insight.

“People think that Peoples Temple is just the story of Jim Jones, and it wasn’t,” says McGehee. Instead, it’s also the story about how people came to follow him, what they believed and stood for, and why they decided to do what they did. And about what happened afterward. “It’s an attempt to show that they weren’t just bodies rotting in the sun,” he says. “They were human beings.”