(Heather Shearer is a professor of rhetoric and writing at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. Her complete collection of articles for this site may be found here. She can be contacted at hshearer@ucsc.edu.)

A complex view of history must necessarily reincorporate in it lovely and creditable things, simply because the record attests to them, as well as to venality and hypocrisy and vulgarity. It is clearly true that the reflex of disparagement is no more compatible with rigorous inquiry than the impulse to glorify.

–Marilynne Robinson, The Death of Adam, 26

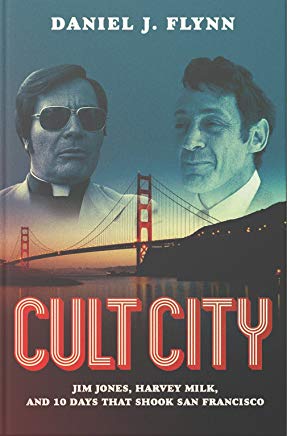

In Cult City: Jim Jones, Harvey Milk, and 10 Days that Shook San Francisco (2018, ISI Books), Daniel J. Flynn repackages and expands upon his earlier work addressing the relationship of Harvey Milk to Peoples Temple. From the book’s title, readers might expect the text to offer a detailed examination of November 18 – 27, 1978, the ten day period between the deaths of Peoples Temple members in Guyana and the assassinations of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and City Supervisor Harvey Milk at City Hall. If so, those readers will be disappointed. Instead, Flynn mainly recounts events leading up to those ten days, twin histories covered in greater detail by other writers.

What sets Flynn’s work apart from others who cover similar territory is his goal of laying blame for the deaths at Jonestown on the heads of San Francisco’s Democratic leadership in particular and social progressives more generally. Of this, Flynn makes no secret, stating that this project was motivated by his quest to attempt to answer the “How?’” of the deaths in Jonestown with the “What?” evoked by the “homage paid to [Jones] at his Temple” by “California’s governor, lieutenant governor, and other leaders” (249). Along the way, he indicts other public figures, including Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Herb Caen and activist-celebrities Angela Davis and Jane Fonda.

His targets will not come as a surprise to those familiar with Flynn’s larger body of work. It includes political commentaries on the Breitbart News website with titles such as “Before Socialism Collapsed Behind the Iron Curtain, It Failed Near Plymouth Rock” and “Before Jane Fonda Called Trump Hitler, She Called Jim Jones a Hero,” as well as books such as A Conservative History of the American Left (2008) and The War on Football: Saving America’s Game (2013). Cult City exhibits Flynn’s characteristic style, a blend of stripped-down reporting and soap-operatic one-liners. (He is fond of closing sections and chapters with short, melodramatic assessments: “Jim Jones did not want [Leo Ryan] to come to Jonestown. Leo Ryan came anyway” (162)). His style is amplified by his focus on the seamy side of his subjects’ histories, such as Jim Jones’ drug use and Harvey Milk’s preference for young males. His lurid retelling of Jones’ and Milk’s histories is unrelieved by few historical details that would complicate his narrative. This narrow focus serves Flynn’s larger purpose: shaming Democrats and liberal social activists for what he sees as their complicity in the deaths at Jonestown.

A Closer Look at Flynn’s Argument

It can be challenging to map out Flynn’s argument because he tries to accomplish a lot in his relatively short book. Not only does he attempt to demonstrate that Democratic leadership in San Francisco was culpable for the deaths in Guyana, he also seeks to upend Harvey Milk’s legacy. In addition, Flynn also devotes a good deal of page space to arguing that Milk-Moscone murderer Dan White was not a conservative, as so many accounts portray him. The best that can be said here is that these topics could be united under the general heading of “San Francisco.”

San Francisco as Fertile Ground for Weirdness and Depravity

Flynn believes the city of San Francisco should share in the blame of the deaths at Jonestown, and this goes beyond the city leadership’s verbal support of Peoples Temple. Early in the book, he absolves the Midwest of responsibility for what Peoples Temple eventually became, writing that “[l]ike most liars, Jones eventually wore out his welcome” in Indiana and that “Jones did not enjoy the political solidarity in Indianapolis that he later received elsewhere. His act wore thin” (16). Flynn interprets the shifting nature of Peoples Temple membership in a similar way, noting that in California, Jones “set out to attract new followers” and that as a result, “Peoples Temple lost is rural Indiana twang” (18). Flynn uses his interview of former Temple member Garrett Lambrev to underscore this shift of midwestern values to California values. Lambrev joined Peoples Temple soon after it settled in Northern California, and had an on-again, off-again membership status for the ten years he was associated with it. Flynn tells us that “The Peoples Temple Lambrev [initially] joined differed greatly from the Peoples Temple he departed for good a decade later. In Northern California in the mid-1960s, he encountered a church drawing its roots from the white, rural Midwest” (20). Later, this was not the case. The implication here is that Californians turned Peoples Temple weird. Flynn sets the stage for this implication early in his book, writing that “the tragedy birthed in Guyana was conceived in California” (6).

Flynn is often direct in his upbraiding of the city. San Francisco is a place where “a diverse cast of characters succeeded . . . after failing elsewhere” (9), a place where “[m]asters of the universe but not of their minds” are indulged (44). The city of the 1960s and 1970s was “an easy place to hide from crimes” and “an easy place to commit crimes,” a place where “the line between political crazies and plain crazies became more difficult to differentiate” (12). He argues that we must consider this context to understand the “relationship between Peoples Temple leader Jim Jones and . . . politician Harvey Milk” – a context of “radical extremism” that “permeated mainstream politics” (12).

He peppers his chapters with historical chestnuts that attribute a long-standing craziness and moral rot to the city. For example, the opening pages of “Chapter 6: ‘I Think They Stole the Election’” explain that “[v]oter fraud and distrust of settling strangers characterized San Francisco from its creation” (79). The book’s final chapter draws parallels between the city leadership’s lack of action on complaints about Peoples Temple and, decades earlier, the city leadership’s refusal to heed Chief of the Fire Brigade Dennis Sullivan’s “pleas for an updated fire fighting system,” a refusal that would have dire consequences for Sullivan and others in the wake of the 1906 earthquake (215). Flynn depicts Congressman Leo Ryan as “the Dennis Sullivan of his day,” noting that both “Ryan and Sullivan heroically labored to save San Franciscans,” but they failed due to “a current of corruption hindering their efforts” (216).

Democratic establishment as complicit in deaths

Flynn’s argument about San Francisco leadership’s complicity in the deaths at Jonestown comprises several points. First, he argues that city leaders of the 1960s and 1970s were incompetent, “fail[ing] more often than not in stopping the nutters, political and otherwise. They failed much more damnably in the case of Peoples Temple. They enabled and empowered Jim Jones” (12-13). Second, he posits that they turned a blind eye to atrocities taking place in the Temple due to Jones’ ability to rally troops in support of political causes – a bit of political quid pro quo. In essence, this relationship boiled down to one in which Jones was valued and supported due to the votes and labor provided by Temple members.

One example he relies on to make this case is the election of George Moscone as mayor. Here, Flynn leans heavily on perceptions that, at the behest of Jones, Peoples Temple members engaged in voter fraud that gave Moscone his narrow victory over John Barbagelata: “Moscone probably owed his election as mayor to Jim Jones and Peoples Temple” (5). The Temple’s work was repaid when Jones was appointed as Chair of San Francisco’s Housing Commission.

Flynn is not the first writer to discuss this topic, but he may be the first to imply that Democratic leadership believed the allegations to be true and ignored them anyway:

The Temple’s influential friends overlooked evidence of severe wrongdoing to actively promote Jim Jones . . . . The cover-ups, the prioritizing of correct politics over right conduct, and the fidelity to the narrative when it clashed with facts led to the faithful’s demise and characterized the mentality of their boosters safe in San Francisco (7).

Of all the city’s leaders, Harvey Milk is singled out as being especially worthy of critique: “Before Peoples Temple drank Jim Jones’s Kool-Aid, powerful people in San Francisco did. Harvey Milk imbibed most enthusiastically” (5); “Harvey Milk, though surely not the most influential politician backing Jones, acted with the greatest zeal in legitimizing a madman” (13). The relationship was mutually beneficial, Flynn points out, offering details about publicity Milk received in the pages of Peoples Forum, as well as material campaign support, including campaign labor and a printing press sold to Milk “for a pittance” during his failed 1976 campaign for the California Assembly. Flynn further notes that Jones’s support came at a time when Milk’s candidacy was not supported by the Democratic establishment (86, 88). Milk repaid Jones by lending his voice in support of Temple causes, sometimes in person, but also in writing.

Indeed, most damning in Flynn’s eyes seems to be the trail of correspondence from Milk on Peoples Temple matters, and this is what he spends most of his time analyzing. Flynn’s discussion relies on five letters sent from Milk either to Jones or to others in support of Peoples Temple and its leader.

Of special interest to Flynn is a letter sent under Milk’s name to President Jimmy Carter in support of Jim Jones and Peoples Temple against allegations made by former Temple members Grace and Timothy Stoen regarding the custody of John Victor Stoen. In an earlier publication (“Drinking Harvey Milk’s Kool-Aid”, 2009), Flynn accuses Milk of libel because in his letter to President Carter, Milk describes the Stoens “as purveyors of ‘bold-faced lies’ and blackmail attempts.” In Cult City, Flynn offers a variation on this theme, accusing Milk of lying to the president in fervid support of Jones: “Harvey Milk so loved Jim Jones that he lied to the president of the United States in order to help him” (151).

Flynn’s critique of Milk goes beyond the city supervisor’s relationship with Jones. His goal is not simply to demonstrate Milk’s connection to People’s Temple but to upend the Milk-as-Hero mythology, as well. Throughout the book, Flynn depicts Milk as a political opportunist and pederast – someone who moved to San Francisco “because that’s where the boys, and the freedom to pursue them, were” (22).

Elsewhere Flynn has described Milk as “an unremarkable subject for the silver screen” and a “short-tempered demagogue who cynically invented stories of victimhood to advance his political career” (Drinking Harvey Milk’s Kool-Aid, 2009). In Flynn’s eyes, Milk’s transgressions are severe enough to corrupt his entire legacy: “To note the tall tales he told about himself and others to further a persecution narrative, the outing of a friend [Oliver Sipple] for political advantage, and his predatory relationships with teens and young men all mark the messenger as indecent” (7, emphasis in original). Flynn’s anti-Milk campaign has been active since at least 2009; his early contributions to Breitbart News, for example, discuss Harvey Milk’s unsuitability as a subject of public honor.

Flynn’s Treatment of Source Material

A generous way of describing Flynn’s treatment of source material is to say that he plays fast and loose with it. A less generous way of describing it is to say that he intentionally misleads readers by overinterpreting evidence, ignoring inconvenient (for his argument) aspects of sources, and perpetuating misinformation.

Offering style in place of substance

Least egregious, but most common, is Flynn’s overinterpretation of facts: absent concrete evidence, he often uses inflated language to make more of something than, it could be argued, he should. Examples of this are too numerous to recount here, but the following examples of overreach should suffice:

- He writes of “Guyanese strongman Forbes Burnham” receiving “letter after letter from important people in the United States reassur[ing] him and other government officials that charges” being made against Jonestown were false (153, emphasis added). His cited sources list only four such letters, however. For many readers, “letter after letter” surely implies more than four.

- He twice uses the phrase “all-in” to describe Milk’s relationship to the Temple (110, 152). This assessment is based on what Flynn views as “support [for the Temple] well into 1978” and Milk’s use of Peoples Temple performers at his 1977 street fair. To many readers, “all-in” implies a dedication involving, at the very least, consistent participation in Temple activities and public identification as a member, neither of which Milk provided.

- He states that “politicians rushed to befriend Jones” (84, emphasis added). While it is true that politicians were keen to capitalize on a relationship with Peoples Temple due in large part to its demographics, Flynn provides no evidence of politicians beating down the Temple’s door.

- In commenting on Harvey Milk’s relationship with Joe Campbell, Flynn writes: “While teaching [math and history at George W. Hewlett High School] failed to keep his [Milk’s] attention long, Joe Campbell, a teenage hustler barely older than Milk’s students, captivated him after a chance meeting at a beach frequented by gays” (24). According to Lillian Faderman’s 2018 biography of Milk (which appears among the sources cited by Flynn), Joe Campbell was nineteen when he and Milk, then twenty-six, began their relationship. So while an age difference existed, it was hardly the Lolita-esque difference implied by Flynn.

In each of the examples described above, there is a kernel of truth that is relevant. The issue is that Flynn pushes his interpretation too far.

At times, however, Flynn’s style pushes overinterpretation into the realm of misinformation. A key example: when writing about Dan White’s defense for the killings of Moscone and Milk, Flynn states that a “psychiatrist brought in by the defense described White as ‘bingeing on Twinkies,’ downing ‘Coca-Cola,’ and gorging himself on junk foods” (211). This is true; a psychiatrist did speak of these things. However, following this statement of fact is commentary typical of Flynn’s reductive, dramatic style, and this commentary crosses the line separating fact from fiction: “He [White] didn’t kill. His diet did. At least the defense relied on that unconventional line of reasoning” (211). Although it is popularly believed that the defense relied on the so-called “Twinkie Defense,” they did not. Instead, it was argued that White’s increased consumption of junk food was a sign of his depressed state, and it was that depressed state that drove his actions. Because Flynn quotes from the trial transcripts, we can assume he read thm, so it is unclear why he makes the erroneous interpretive leap that he does.

Misrepresenting sources and subjects

It could be argued that Flynn’s stylistic indulgences should be overlooked because it is the reader’s responsibility to interrogate claims, especially those made with inflated language like Flynn uses.

It is trickier, though, to overlook instances where Flynn misrepresents the context of his sources to force his argument. For instance, he calls “publisher, physician, and civil rights leader” Carlton Goodlett to task for describing the “concentration camp” of Jonestown in edenic terms. But he fails to tell readers that Goodlett’s comments were made to Jonestown’s residents during a visit in Fall 1978 (176). That is, Flynn’s handling of the source implies that Goodlett was speaking to others – fellow politicians, perhaps, or reporters – about Jonestown, not to Peoples Temple members themselves.

Flynn is also apt to ignore facts that contradict or complicate the narrative he sets out to construct. One especially troublesome instance of this involves Flynn’s discussion of Harvey Milk’s support of Peoples Temple, especially his letter to President Carter in support of the Temple. To emphasize his point about Milk’s close relationship with Jones, Flynn quotes Michael Bellefountaine’s (A Lavender Look the Temple: A Gay Perspective of the Peoples Temple, 2011) assessment of the letter as “‘somewhat disturbing in that it reads as if it were written by a Temple publicist” (qtd in Flynn, 148).

In fact, Bellefountaine is careful to qualify his observations about the origin of the letter. Very near the passage quoted by Flynn, Bellefountaine notes that the letter to President Carter could very well have been written by a Temple publicist:

In reviewing this letter in more recent years, Milk aide Daniel Nicolletta expressed concern that [the letter] did not read as though it had come from his former boss and friend. Indeed, the letter to President Carter is very different from the rambling letter Milk wrote to the Prime Minister of Guyana almost six months earlier. The differences between the letters may be explained by a memo within the Jonestown files concerning a similar letter to Carter signed by State Assemblyman Willie Brown. The memo states that Brown would change the wording of the Temple’s draft letter to the president (Bellefountaine & Bellefountaine, 2011, “The Allegations,” para. 30).

Even if the letter to Carter were ghost-written, Flynn could have made a relevant point (i.e., Milk lent his name in support of Peoples Temple). So his omission of information related to the letter’s authorship is perplexing, until one realizes that unless one believes the hype(erbole), there is nothing new in Flynn’s text that others have not addressed.

We see another example of selective use of source information in Flynn’s discussion of Milk’s personal relationship with Jack Galen McKinley. Relying on Shilts’ The Mayor of Castro Street, Flynn present McKinley as being sixteen, below the age of legal consent in New York State, when he entered into a sexual relationship with the 33-year-old Milk.

Other texts, however, such as Faderman’s (2018), report McKinley’s age at the time of his relationship with Milk as seventeen, the legal age of consent in New York State. To establish McKinley’s age, Faderman relies on Milk’s address book, which contained notations about his contacts’ birth dates, and a correction to Shilts’ book contained in Vince Emery’s (2012) The Harvey Milk Interviews: In His Own Words. Emery claims that for Shilts’ age calculation to be accurate, Milk and McKinley would have had to begin their relationship when McKinley arrived in New York City, which was not the case (Emery, 342, as described in Faderman, 2008, endnote 3, Chapter 4: Will-o’-the-Wisps).

Faderman and Flynn both had access to the same resources, and Flynn cites Faderman’s book elsewhere in his own work. The larger point, then, is not McKinley’s age – while there was a legal tipping point between sixteen and seventeen, even at seventeen, the age difference between the Milk and McKinley could be expected to make an impression, and for many, not a positive one – but rather that in obscuring information, Flynn shows himself to be an unreliable reporter.

This perception of unreliabilty may cause some readers to question what Flynn actually discovered during his interviews. Here I think in particular of several statements offered from his April 11, 2016 interview with Tim Stoen. During this interview, Stoen noted that he “’never had any interactions with [Milk] at all’ and he ‘did not see [Milk] as a member’” of Peoples Temple (148). These statements seem to undercut Flynn’s claims of Milk being inextricably bound up with the Temple and with Jones.

Flynn’s mishandling of source material is exacerbated by the fact that it is challenging to get a handle on the scope of his sources. Cult City lacks a comprehensive bibliography, offering instead only endnotes organized by chapter. The usability issues created by this editorial decision are magnified by the fact that Flynn rarely provides in-text information that would help readers to understand where he is getting his information. Moreover, sometimes the placement of his citations adds to the confusion, as is the case, for example, with endnote 21 on p. 193. The passage in question involves a sentence about Joe Wilson’s affidavit regarding Grace Stoen’s character and a sentence about Joe Wilson’s behavior on the days of the deaths in Jonestown:

Joe Wilson, who had earlier testified in an affidavit to Grace Stoen’s unfitness as a mother by claiming she often rubbed roughly against his private parts and occasionally pranced by him totally nude, more effortlessly took on the role of enforcer. Now, like the woman against whom he bore false witness [Grace Stoen], Wilson desperately searched for his son, who had escaped Jonestown on his mother’s [Leslie Wagner-Wilson] with the “picknickers” that morning.21

Readers who consult the endnote will see that it provides a citation for Joe Wilson’s affidavit of August 13, 1977. In this affidavit, Wilson does discuss Stoen’s alleged behavior. However, the placement of the footnote in the body of the text suggests that the source also corroborates the description about Wilson’s behavior on the day of the deaths. It does not.

For the most part, the sources that Flynn does use are relevant: primary source material from archives, interviews with people involved in the events he covers, newspaper articles that discuss the events, and secondary sources about Milk and Peoples Temple. But Flynn isn’t as choosy as he could be. Included among Flynn’s sources is David Talbot’s Season of the Witch: Enchantment, Terror and Deliverance, a text that Flynn himself (“Flower Colored Glasses,” 2012) has disparaged as being “fatally weaken[ed]” by the “author’s questionable judgements,” and he suggested that Talbot’s “ideological obsessions spawn more delusions than LSD.” If Flynn does not trust Talbot’s work, then why should Flynn’s readers?

It is notable, however, that he has ignored nearly the entire universe of scholarly work on his subjects. Most lamentable is Flynn’s ignorance of John R. Hall’s comprehensive analysis of Peoples Temple (Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History, 2004), which offers a conspiracy-free explanation for some of the legitimate complaints raised by Flynn. For instance, in discussing the quid pro quo relationship between Jones and government leaders, Hall is comprehensive, citing the relationship Peoples Temple built in Mendocino County with Republican leaders (see, for example, p. 153) as well as the relationship with San Francisco’s Democratic establishment. In addition, Hall underscores the fact that, rather than being an unusual example of political cronyism, the Temple’s success speaks instead “to the nature of political process more widely. What Peoples Temple did reveals as much about the conventional worlds of public relations and politics as it does about Peoples Temple” (170-71). That is to say, this was business as usual in the world of politics.

Additionally, Hall’s book, as do a number of other scholarly sources (for example, Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, 2004; Hearing the Voices of Jonestown, 1998), provides a counterpoint to Flynn’s insistence that Peoples Temple was not religious. Because so much of Flynn’s purpose involves condemning Peoples Temple as atheist and Marxist/socialist/communist (Flynn seems to use the political terms interchangeably), I would have liked to see him grapple with this issue more strenuously. He is too quick to ascribe Jones’s personal views to the views of Peoples Temple members as a whole, an error of synecdoche that allows him to depict Temple members who joined and stayed as humans without personal agency.

Conclusion

Cult City will undoubtedly be valuable to those seeking to confirm their views of left-coast “weirdness” and those wanting to read a brief, lurid history of Peoples Temple, Jones’s past, Milk’s legacy, and Dan White’s trials and tribulations.

Readers familiar with Peoples Temple history and Milk’s background in all of their complexity, however, might find themselves puzzled, and perhaps even angered, by Flynn’s book, less because of what it highlights and more because of the attitude that Flynn takes toward his subjects. He eschews decorum for one-liners, and, some might say, badgers readers with his own soapbox pronouncements. In addition, his handling of sources throws suspicion onto the text as a whole. Even so, a certain segment of readers who are not part of Flynn’s choir can still find value in making a study of the book. Cult City is, after all, a good example of a certain type of text about Peoples Temple, and in this way it can usefully figure as part of a meta-analysis of the literature.

It could also be argued that this book is an excellent example of a particular brand of conservative identity politics. In one version of his biography, Flynn described himself as being brought up in “the Bluest part of the Bluest state,” where he was “[p]hysically attacked by aging hippie ‘Free Mumia’ supporters, mooned and shouted down by Berkeley book burners, [and] banned for life from Black Panther reunions,” among other injustices. He credits his upbringing with aiding “his anthropological fieldwork among Leftist Americanus” (Flynn Files Bio, Web Archive). Those seeking to study the product of Breitbartian reasoning and its concomincant rhetorical techniques could do worse than to choose Flynn’s text.

References

Bellefountaine, M. & Bellefountaine, D. (2011). A Lavender Look at the Temple: A Gay Perspective of the Peoples Temple, [Kindleedition]. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse.

Faderman, L. (2018). Harvey Milk: His Lives and Death. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Flynn, D. J. (2009). “Drinking Harvey Milk’s Kool-Aid.” Accessed February 4, 2019 at https://www.city-journal.org/html/drinking-harvey-milk%E2%80%99s-kool-aid-10574.html

Flynn, D. J. (2012). “Flower-Colored Glasses: David Talbot Cannot See San Francisco, or the Sixties, with Anything Like Objectivity.” Accessed February 4, 2019 at https://www.city-journal.org/html/flower-colored-glasses-9733.html

Flynn, D. J. (2013). “Biography.” Flynn Files. Accessed January 2, 2019 at https://web.archive.org/web/20130906161342/http://www.flynnfiles.com/bio.php

Flynn, D. J. (2017). “Before Socialism Collapsed Behind the Iron Curtain, It Failed Near Plymouth Rock.” Breitbart News. Accessed February 4, 2019 at https://www.breitbart.com/politics/2017/11/22/flynn-socialism-collapsed-behind-iron-curtain-failed-near-plymouth-rock/

Flynn, D. J. (2018). “Before Jane Fonda Called Trump Hitler, She Called Jim Jones a Hero.” Breitbart News. Accessed February 4, 2019 at https://www.breitbart.com/entertainment/2018/11/03/daniel-flynn-before-jane-fonda-called-trump-hitler-she-called-jim-jones-a-hero/

Hall, J. R. (2004). Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick: Transactions Publications.

Maaga, M. M. (1998). Hearing the Voices of Jonestown. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Milk, H. (2012). Ed., V. Emery. The Harvey Milk Interviews: In His Own Words. San Francisco: Vince Emery Productions.

Moore, R.; Pinn, A. B.; & Sawyer, M. R., eds. (2004). Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press.

Robinson, M. (2005).The Death of Adam: Essays on Modern Thought. New York: Picador.

Shilts, R. (1982). The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Talbott, D. (2012). Season of the Witch: Enchantment, Terror and Deliverance. New York: Free Press.