May 25, 2009

This is no one’s fault. I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again– I just need a little peace. I just need the wheels to stop turning and nothing coming of it, like a frozen computer. I am 28 years old and still unable to meet challenges in life with enthusiasm and “embrace the suffering,” as a Buddhist might say.

It’s been 13 years since I was sexually assaulted. It’s been 2 years since my breast surgery. It’s been 5 years since I overdosed on codeine. It’s been 3 years since I got married. It’s been 4 months since I had Bronwen.

Through no fault of her own (in fact, it may have been a gift she has), she taught me what most parents learn– we don’t have the answers to much. Trouble is, I don’t have the strength to admit ignorance and seek out the answers.

It’s been 6 months since I completed my Bachelor’s. Yes, I spent time searching in the library, trying desperately, as I always do. But it only heightened my awareness to the idea that I can’t do anything truly productive.

So Bronwen, I know you’re a sensitive girl. I know you’ll always feel badly, like you caused this. But you didn’t. Don’t ever think I didn’t love you or want to see you grow up. There’s so much history here that surely you’ll learn about one day. You are Bronwen after Bronwen Wallace, my favourite poet. She was a real fighter for women’s rights and this informed her poetry. Despite her success she was a “regular” person. I hope the same for you. I’m really glad you’re here even though I can’t be.

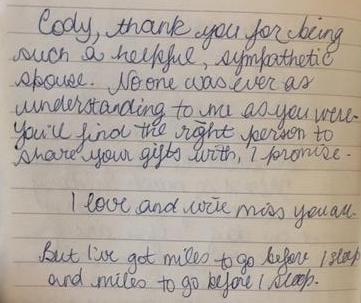

Cody, thank you for being such a helpful, sympathetic spouse. No one was ever as understanding to me as you were. You’ll find the right person to share your gifts with, I promise.

I love and will miss you all.

“But I’ve got miles to go before I sleep

And miles to go before I sleep.”

I wrote that note after swallowing more than 100 tablets of the various psych meds I’d been prescribed during the first few months of my daughter’s life. It’s a strange thing to look back at such a document, having survived another decade after it was written. The cursive got very scrawlish at the end of the note, as it took about 20 minutes to write and by then all the clonazepam, seroquel, disapramine, prozac, and codeine were taking effect.

I wrote that note after swallowing more than 100 tablets of the various psych meds I’d been prescribed during the first few months of my daughter’s life. It’s a strange thing to look back at such a document, having survived another decade after it was written. The cursive got very scrawlish at the end of the note, as it took about 20 minutes to write and by then all the clonazepam, seroquel, disapramine, prozac, and codeine were taking effect.

Yet I regained consciousness two days later, on May 27, 2009. I was the angriest I’d ever been. I was covered in bruises on my chest. My husband told me they were rubbing my sternum very hard when they found me. I was face down on the bed, eyes open. They were not sure if I would recover because my blood pressure was so low and I’d been alone in my coma for some time before I was found. Having said that, I was beside myself with rage when my eyes dared open to the dimmed area of the emergency ward where they were monitoring me. I had an IV pole and oxygen in my nose. The curtains were drawn so no one could see me among the extra towels.

Before this suicide attempt, I used to compare myself to the disposable society in which we live. I used to compare myself with the used car we bought. Eventually you ditch the car when repairs are no longer “cost effective.” I was not worth the work anymore; my chassis was ruined after giving birth. I soon started calling myself a classic lemon. I was simply exhausted from the process of trying to make lemonade with my life. I was working so hard and getting nothing to drink. And I was thirsty.

I was not in Jonestown or in Peoples Temple. My only connection to 1978 is that my parents were married that year. Whenever I see those wedding photos of two youngsters, I can smell mom’s Toni Home Perm, feel that scratchy brown polyester suit dad had on, and hear ballads by the Carpenters. I got a similar feeling of intoxication while watching footage of those who went to Guyana to begin construction. The work would be back-breaking, but the reward would be a better world. And that’s simply the blindest love and faith I’ve ever seen.

My parents would separate and divorce in 2005. That soft-focus wedding image that hung on the wall in every family home would come down for the last time. Mom and dad had been blind, regained sight, and didn’t like what came back into focus, I guess. It’s a distressing moment as a child of two people who now wanted nothing to do with each other, even though I was not a child anymore. But one strong trait both parents had was commitment. My sister and I were adults, no longer in the home when dad wanted to leave.

The notion that a couple should stay together for their children has always baffled me. What kind of “service” do people think they provide for their kids if they force themselves to stay married? I don’t know. But I did learn that I was a problem. And when our daughter Bronwen was born, I was even more of a problem.

I never wanted to cause anyone any pain. I truly meant what I said in the note. I really wanted my daughter and husband to go on and have great lives. I just couldn’t imagine that greatness including my presence. How could it? I was barely treading water for a long time. I was a boat anchor pulling my husband down with me, and to protect our daughter, I was dealing with the problem: my body. I was convinced all I could do was take up space and incur expenses. I could contribute nothing. And I was raised never to burden anyone.

Living in an old psychiatric wing in the hospital is interesting. I was there for two months under strict observation. I saw patients come and go, whether that be through appropriate channels or by escape or sneaking back in. I saw people admitted and discharged and re-admitted. I saw people taken away in wheelchairs to the ECT operating theatre, brought back passed out on themselves, dumped back into bed where they would sleep for the rest of the day. I saw my baby go from a swaddled “spud” to sitting up and holding her feet. Everyone around me was actively trying to affect change. I simply had no energy to do so.

While in this weird old wing, known as the Pavilion, I watched the news and saw that the world was going through a lot of loss. Michael Jackson died. I was angry at him for getting away with that. If only I could get my hands on Propofol, I thought, with my strong sense of gallows humour. Farrah Fawcett died, and Patrick Swayze was very sick. Who was I? Why did my survival matter so much?

That’s what happens to the depressed mind, I’m afraid. There’s a pervasive sense of inadequacy, lack of value, lack of desire. It’s like being a walking corpse. You’re ambulatory, your body works as it should, but you have nothing but horrendous thoughts floating around. I was so plagued by all of that and the pressures of being a new mom.

I sat up and listened to Christine Miller’s voice in a documentary. She didn’t sound afraid for her own life, but wanted to save the children. Her pleas made sense to me because that’s the way I felt. I wanted to pay the piper for everything wrong I may have done and spare my daughter from undue suffering. I felt caught in a brave new world that I couldn’t escape.

Unfortunately that two-month stay would not be the last. I was hospitalized again three years later. But learning about those who travelled to Guyana to build a new hope, and whose hearts were so big and open and honest to a fault, helped me understand myself. I feel like, in some ways, I can understand what happened and hope that this shard of insight can help you in return. For I have nothing else to offer.

(Danielle Walker holds a degree in creative writing and poetics from the University of Victoria (2008). She lives with her husband Cody, her daughter Bronwen – who is now 10 years old – and three cats, Henry, Sophia, and Victoria, in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia, Canada. Her other contribution to this site is Greetings. She can be reached at recordthis@shaw.ca.)