(Editor’s note: This article was originally published in Communal Studies, Communal Studies Association (Vol. 38, Issue 2, December 2018).)

(Rebecca Moore is Professor Emerita of Religious Studies at San Diego State University. She has written and published extensively on Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Rebecca is also the co-manager of this website. Her other articles in this edition of the jonestown report are Women’s Roles in Peoples Temple and Jonestown (co-written with Catherine B. Abbott) and Jonestown in American Religious Life. Her collection of articles on this site may be found here. She may be reached at remoore@sdsu.edu.)

Four decades after the disaster that occurred in Jonestown, Guyana, it is worth asking if there is anything more to be learned or discovered. Articles, books, films, and documentaries have told and retold the story of the mass deaths in the jungle. Dozens, and perhaps hundreds, of writers have assessed the impact of Peoples Temple–the religious movement behind Jonestown–and its members. Yet a major part of the narrative remains ignored: the narrative told from the perspective of African Americans, who made up the majority of residents of the Jonestown community.

This article looks at the ways in which the African American experience in Peoples Temple has been erased from public consciousness. The presence of African Americans looms large but always in the background–behind all the books and headlines, behind all the photos and documentaries. This article plans to bring their story into the foreground.

I first introduce the subject of erasure: What exactly do we mean by that? What are the implications of a people, or a history, being erased? I then consider the facts of the erasure of African Americans from narratives about Jonestown, discussing who lived there, who died there, and what we know about them. The article next outlines the contours of re-inscription–that is, the way that people of color are retelling the Jonestown story and giving the black members of Peoples Temple a voice. Finally, I close with some conclusions that note potential pitfalls in overcorrecting for erasure.

Erasure

What do we mean when we speak of erasure? We know what it means to wipe the slate clean, to blot out an error, or to white out a mistake. Racism is institutionalized throughout American society. It exists in the very structure of our lives: our schools, our legal system, our political organizations, and our labor, health, and environmental institutions. It’s everywhere.

Erasure signifies the conscious and unconscious ways in which we ignore these facts of life. Thinking we can be colorblind in a racially structured order denotes erasure. Some educators in composition classes today call race an “absent presence” and racism, an “absent absence” among their students.[1] In the field of political theory, one analyst has identified a “politics of extinction.”[2] By this she means that the academic majority either ridicules, dismisses, or neglects the voices of advocates of critical race theory and feminist theory. These voices are extinguished. That’s erasure.

In a groundbreaking study conducted in 1984, the legal theorist Richard Delgado conclusively demonstrated the existence of a tradition “of white scholars’ systematic occupation of, and exclusion of minority scholars from, the central areas of civil rights scholarship. The mainstream writers tend to acknowledge only each other’s work.”[3] Delgado showed that despite the progress made through civil rights legislation, white scholars continued to dominate the field of civil rights law.

We don’t have to look very far to find examples of erasure in our nation’s history. My students at San Diego State University did not know that African immigrants made up nearly 20 percent of the population in the thirteen American colonies, and in some Southern colonies, that figure approached fifty percent. I always had a few students in my classes who had never heard of Japanese internment during World War II. This surprised me, given the fact that the Manzanar internment center was located just three hundred miles away. And literally no one knew that close to a million Mexican Americans–most of them US citizens, many of them children–had been deported to Mexico during the Great Depression. They were simply shipped back under orders from President Herbert Hoover. That’s erasure, the obliterating of a people’s history.

Erasure is not the same as merely forgetting. Erase is a transitive verb–it has an object. Something is erased by someone or something else. Thus, erasure indicates one of the key elements of a race-based society: the active attempts to maintain the status quo by pretending that race and racism do not exist.

In 1952 Ralph Ellison captured the existential problem of erasure for black Americans in his novel Invisible Man. By dropping “the” from invisible man, Ellison emphasized complete obliteration. He’s not an invisible man, or the invisible man, but simply invisible. His comments about the contradiction that exists between what is recorded in history and what is not are relevant. “All things, it is said, are duly recorded,” his unnamed narrator observes. “But not quite, for actually it is only the known, the seen, the heard and only those events that the recorder regards as important that are put down, those lies his keepers keep their power by.”[4]

In other words, history is written not only by the winners–as George Orwell said in 1944–but also by those in power in order to retain their power.

More recently, Percival Everett addressed the problem of erasure in his eponymous satire, erasure.[5] In a nutshell, the book’s protagonist, Thelonious Ellison, virtually disappears when he writes a violent, misogynistic, nihilistic first-person account of a thug under a pseudonym. His other novels have not been “black enough,” according to his literary agent. (As a side note, Ralph Ellison’s invisible man overhears a white woman ask if “he should be a little blacker.”[6]) Thelonious Ellison goes overboard to be black in the novel-within-a-novel titled “My Pafology.” By the end of the book–spoiler alert here–Ellison seems to have become subsumed into his alter ego–a tough, violent, black ex-con. His hero has been erased.

Along with Everett’s other works, erasure raises significant questions about race and identity. What does it mean to be black? What is blackness? And who gets to decide? Clearly there is no single answer to these questions; nor should there be. That’s part of Everett’s project, to undermine the essentialism that accompanies both contemporary identity politics and white racism.

This gets us to narratives about Jonestown and Peoples Temple. What did it mean to be black in Peoples Temple? Who made the decisions about this? Most importantly, how has the story of Jonestown been told in the media and popular culture?

The general public was introduced to Peoples Temple through the horrifying images of the deaths that occurred in Jonestown. As far as the world was concerned, that was the beginning and ending of the Peoples Temple story. In order to understand November 18, however, we need to take a look at the movement that preceded it.

Peoples Temple began as an interracial church in Indianapolis in the mid-1950s. About eighty members, both black and white, moved to California in the mid-1960s, where the Temple became a large, progressive presence. And in the mid-1970s, about a thousand members immigrated to the South American country of Guyana, where they attempted to establish a socialist utopia in the jungle.

There are numerous narratives as to what happened on the final day. It is clear that a handful of young men from Jonestown assassinated Congressman Leo Ryan, and deliberately shot and killed three journalists; they seemed to have accidentally killed a Jonestown defector who was leaving with Ryan. Back in the jungle community, six miles away, people gathered in its central pavilion, where they ingested poison. They had practiced this ritual at least a half dozen times before.

There is ongoing controversy as to whether we should call the deaths murder or suicide.[7] There is no question that the children were murdered: they had no choice. It’s likely that many senior citizens were also murdered. The question that persists is whether those remaining voluntarily drank the poison. Although there were armed guards, they too died in the ritual. And as the Guyana police commissioner who investigated the deaths asked, who would want to live after seeing their children die? Alternative accounts have arisen that claim the residents were killed by outside forces, by mercenaries, by British troops, or by American soldiers. Other accounts claim that Leo Ryan was the real target or that Jonestown was a mind control experiment or that it was the testing ground for a neutron bomb.

While very important, these questions miss the larger picture: What was Jonestown? What did it signify then, and what does it signify today? And, in terms of this article, what does it mean for African Americans?

As the terrible news trickled out, most of the people who knew about the Temple and spoke to the press were white. Some had left the Temple long before Jonestown. They had raised alarms earlier so reporters knew them. A number of relatives had traveled to Guyana with the congressman and his party and were also available to the media: most, though not all, were white. Others fled Jonestown that day, sent out by the group’s leaders to deliver money to the Soviet embassy. Thus, the story of Jonestown was primarily narrated by white former members. These apostates, as they are called, were critical of the organization, which was the reason they had left the Temple in the first place.

Full disclosure here: my sisters were part of the leadership group in Peoples Temple and helped plan the deaths. They too died in Jonestown, along with our nephew. Because my parents and I were outsiders, and not part of any organized oppositional group, we offered a different perspective. That means we too were called upon for interviews and news articles to offer yet another angle on the subject that dominated headlines for close to two weeks. Nevertheless, our perspectives were those of white people.

It would be a mistake to think that there were no African American voices telling the story of Jonestown from the very beginning. We have only to think of the analyses by C. Eric Lincoln, Archie Smith Jr., Muhammed Isaiah Kenyatta, and others to know that was not the case.[8] Moreover, two nonfiction accounts presented the experiences of African American Temple members Stanley Clayton and Odell Rhodes.[9] But in the years that followed, these narratives were eclipsed by the dominant, white narrative.

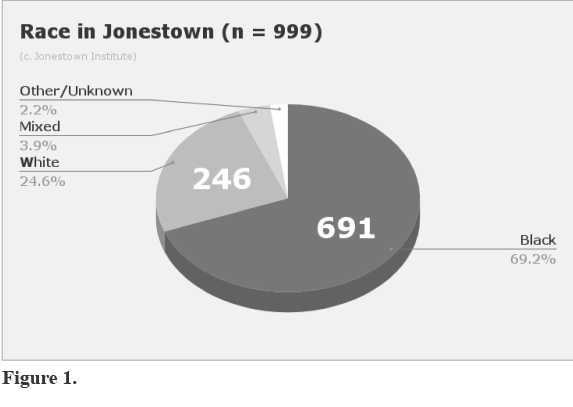

Race in Jonestown (n = 999)

Race in Jonestown (n = 999)

(c. Jonestown Institute)

Black 69.2%

White 24.6%

Mixed 3.9%

Other/Unknown 2.2%

Note: Table made from pie chart.

Thus, the overrepresentation of white subjects in news stories erased the presence and importance of African Americans in Jonestown and in the movement. Several charts and graphs clearly demonstrate this. About a thousand people moved to Jonestown over the course of 1977 and 1978. Almost 70 percent were African American (Figure 1). This percentage is actually far lower than the racial proportions that existed in the United States, where more than 90 percent of the Temple members were African American.

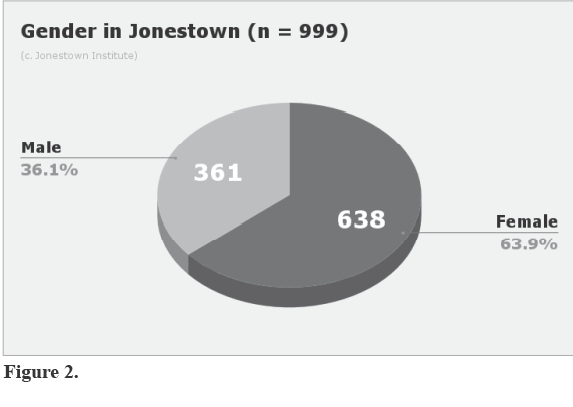

Gender in Jonestown (n = 999)

Gender in Jonestown (n = 999)

(c. Jonestown Institute)

Female 63.9%

Male 36.1%

Note:Table made from pie chart.

Almost two-thirds of the residents–64 percent–were female (Figure 2). Why were there so many more women than men? These statistics bear out the conventional wisdom that says that female membership in religious groups generally tends to be greater than that of men. Another possibility comprises the life care packages Peoples Temple offered to senior citizens, along the lines of retirement programs available from other religious organizations. Moreover, general population statistics show that older women outnumber older men because they outlive them. The fact that 16 percent of those living in Jonestown were females sixty-one and older suggests this as likely.

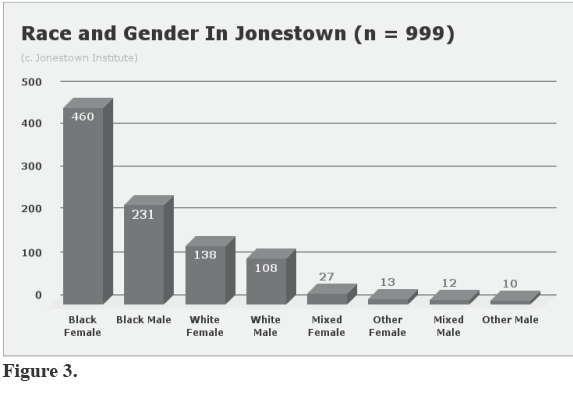

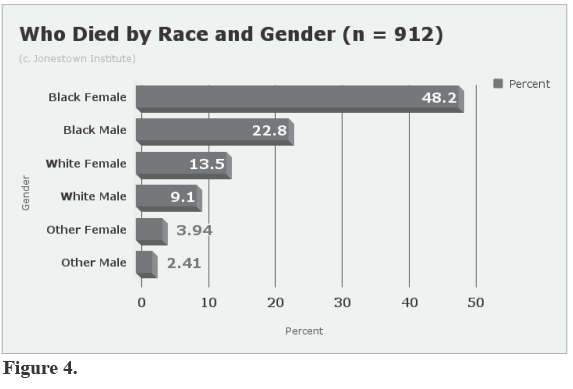

If we look at race and gender together (Figure 3), we see that almost half of the residents were black females and almost a quarter were black males. This ratio continues when we look at who died in Jonestown (Figure 4).

Both of these charts are a bit misleading, however, because they may not accurately represent the number of biracial individuals living in Jonestown, especially children. Some people identified as black in the records may in reality have been of mixed race. Although this is less of a problem for children, since their parents were known and could be racially identified, it was a greater problem for adults, where racial heritage was unknown. Some individuals were identified as black by virtue of skin color rather than parentage. Related to this was the issue of transracial adoptions. Peoples Temple members seemed to follow national trends in the United States, in which white parents adopted, or fostered, black children at a higher proportion than black parents adopting or fostering white children.

Race and Gender In Jonestown (n = 999)

Race and Gender In Jonestown (n = 999)

(c. Jonestown Institute)

Black Female 460

Black Male 231

White Female 138

White Male 108

Mixed Female 27

Other Female 13

Mixed Male 12

Other Male 10

Note: Table made from bar graph.

Who Died by Race and Gender (n = 912)

Who Died by Race and Gender (n = 912)

(c. Jonestown Institute)

Gender Percent

Black Female 48.2

Black Male 22.8

White Female 13.5

White Male 9.1

Other Female 3.94

Other Male 2.41

Note: Table made from bar graph.

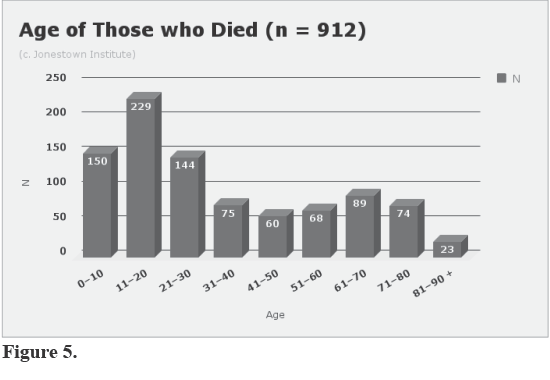

Age of Those who Died (n = 912)

Age of Those who Died (n = 912)

(c. Jonestown Institute)

Age N

0-10 150

11-20 229

21-30 144

31-40 75

41-50 60

51-60 68

61-70 89

71-80 74

81-90+ 23

Note: Table made from bar graph.

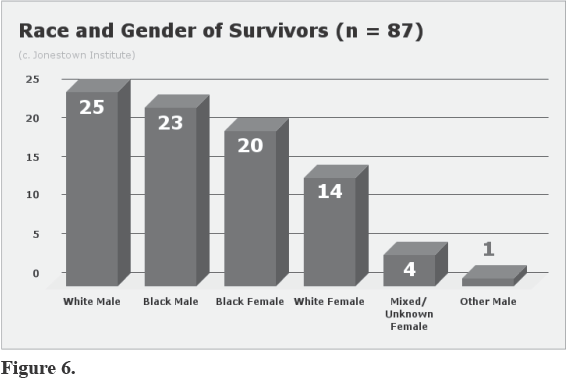

Race and Gender of Survivors (n = 87)

Race and Gender of Survivors (n = 87)

(c. Jonestown Institute)

White Male 25

Black Male 23

Black Female 20

White Female 14

Mixed/Unknown Female 4

Other Male 1

Note: Table made from bar graph.

It has long been known that many children died in Jonestown, but Figure 5 dramatically illustrates this. There were 379 children and young adults aged twenty and under who died. Coupled with senior citizens aged sixty-one and older, we have a sizeable nonproductive workforce. Of course, many teenagers worked in Jonestown, as did many of the senior citizens. Few escaped the hard physical labor demanded by an agricultural project situated in a tropical jungle. Moreover, Social Security checks of retirees totaling more than $36,000 per month helped support the community financially, as did various cottage industries–such as soap- and doll-making–in which seniors were engaged. In other words,

African American senior citizens contributed significantly–both financially and in their work–to the Jonestown enterprise.

Only eighty-seven people, or less than one-tenth, of the total Jonestown community survived (Figure 6). The disproportionate number of male survivors reflects the fact that the basketball team, comprised solely of young men, was playing in Guyana’s capital city of Georgetown. In addition, five men and a single woman were aboard two different boats–one in the Caribbean and the other on the Kaituma River–as the deaths were occurring.[10] Other men and women were in the capital city for various reasons.

What is noteworthy is the number of African Americans who actually made conscious decisions to survive that day. Eleven left Jonestown on the morning of November 18, including two family groups; they pretended to go on a picnic and then fled up the railway tracks toward Matthews Ridge, twenty-eight miles away.[11] Leslie Wagner-Wilson calls Richard Clark the “Black Moses” who saved her, her young son, and her companions by leading them past the security guards and to safety.[12] Using some quick wits, two young African American males also escaped as the deaths were occurring, and an elderly black man hid himself in a ditch.

While all of these numbers and charts say a great deal, they don’t tell the whole story. We need to look closely at the paradox of race in the Temple. On the one hand, blackness was valorized, rhetorically speaking. Jim Jones identified with oppressed peoples, and variously claimed to be African American or Native American. More frequently, he would tell the congregation that they were all niggers regardless of race. “We all say in here,” he confessed in 1972 to a visitor at the congregation, that “we’re all niggers, or we wouldn’t be here, white, black, and brown, we’re all niggers.”[13] On numerous occasions, he declared bluntly that he was black. “We who are black,” he stated in 1977, “we have seven times more blood pressure problems, six times more likelihood of getting heart disease, four times more likelihood of getting cancer.”[14] Thus to live in solidarity with the oppressed, for Jones, was to be black.

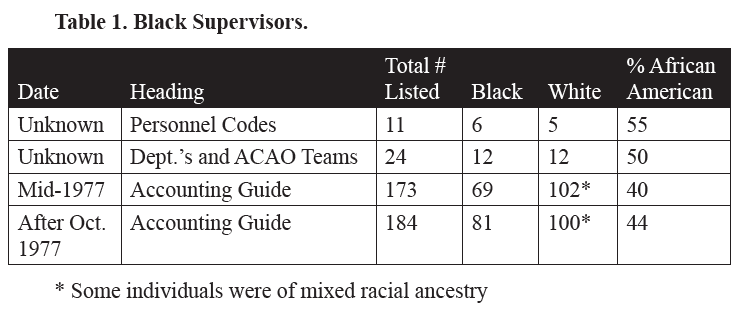

Nevertheless, there were few African Americans at the highest levels of authority, either in California or in Guyana. Real power remained with Jones and a cohort of white, predominantly female, advisers. A tally of department supervisors drawn from the Temple’s own records shows a decline in black leadership in Jonestown as time passed, though there is a slight bump after October 1977, the latest data we used (Table 1).[15]

When we evaluate the number of African American supervisors and department heads compared to the total community, we see that they are greatly underrepresented. Although blacks made up close to three-quarters of the population, they accounted for less than half of the leadership in 1977.

When we evaluate the number of African American supervisors and department heads compared to the total community, we see that they are greatly underrepresented. Although blacks made up close to three-quarters of the population, they accounted for less than half of the leadership in 1977.

There is also the question of whether African Americans performed manual labor at a rate disproportionate to that of whites. Don Beck, a former Temple member who analyzed a large number of records from Jonestown, came up with a total of 250 individuals working in “Agriculture and Livestock.”[16] These included categories such as animals, gardens, insecticides and fertilizers, land clearing, land cultivation, orchards, and more. The record of laborers in the category “work crews” was 121, with 26 of the workers being white; thus 20 percent of the field hands were white, a bit less than the 24.6 percent of whites living in Jonestown. With 70 percent of the residents being African American, we would expect to see blacks outnumber whites in all categories by a factor of three. As noted, however, this was not the case when it came to leadership roles.

Work assignment begs the questions of who benefited and who was exploited in Jonestown. As early as 1980, two University of Guyana sociologists called the agricultural project “The Jonestown Plantation.”[17] Professors Lear Matthews and George Danns argued that the relationship between Jim Jones and his followers was that of master to slave, especially in Jones’s use of white lieutenants to carry out orders. African Americans were brought to Jonestown “under slave-like conditions,” in which they gave up all their possessions, were cut off from their families, and “were forced to become tools of production.”[18] Like the colonial plantation systems, Jonestown was a total institution, which carefully scheduled and closely monitored its inhabitants’ (read: slaves’) activities. Moreover, harsh punishments were meted out to control dissent and to prevent escape. “Jonestown was an atavism,” they concluded, “a recreation of a slave plantation with similar characteristics.”[19] If freedom of movement had been available, then the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project might have become a model utopianist community. Without that liberty, however, blacks and whites alike were slaves. Thus, the characterization of Jonestown as a plantation has some truth to it, despite the racially charged nature of the word “plantation.”

In 2004, I published an article in which I concluded that as an institution, Peoples Temple was not only racially black but also culturally black.[20] By “racially black,” I meant, and continue to mean, that African Americans made up the vast majority of members, residents, laborers, and leaders who contributed to the growth, dynamism, and financial support of Peoples Temple. By “culturally black,” I intended to say that the Temple embodied one type of black religious style in its progressive worldview, its worship practices, and its goal of a this-worldly, rather than other-worldly, paradise. Did this style, however, express the substance, rather than just the appearance, of black religion?[21]

As long as the Temple was led by a white preacher who surrounded himself with a corps of white operatives, the cultural blackness of Peoples Temple must remain problematic. Nevertheless, the sheer density of the black experience woven into the fabric of Temple life should not be ignored. In fact, the erasure of this experience from the narrative requires a new approach, one that takes into account African American voices and views.

The Contours of Re-inscription

In an essay titled “Discourse in the Novel,” the twentieth-century Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin observed that certain social groups evolve as “forces that serve to unify and centralize the verbal-ideological world.”[22] These groups employ a hegemonic language that tries to suppress the plurality of voices that exist in the real world, by valuing unity over diversity. This is especially true in literature, which was what Bakhtin was discussing, but it’s also true of the wider society. These dominating forces attempt to create a “stable nucleus of an officially recognized literary language”–what he calls “centripetal forces,” for they strive for ideological and linguistic unity.[23] They attempt to hold things together, by excluding or erasing alternative visions.

Pulling against these official narratives–or rather, coexisting alongside the centripetal momentum–are centrifugal forces that decentralize, destabilize, and disunify the mainstream narrative. “Indeed,” as Bakhtin writes, “any concrete discourse … finds the object at which it was directed already as it were overlain with qualifications, open to dispute, charged with value, already enveloped in an obscuring mist.”[24] In plain English, stories and texts do not exist in a vacuum. They’re already loaded with meaning.

When we turn to representations of Jonestown, then, we find that any attempt to describe it already faces a “tension-filled environment of alien words, value judgments and accents.”[25] Despite mainstream efforts to tame it, Jonestown retains an extremely controversial valence that is far from neutral. Therefore, when we depart from established narratives about “what happened,” we see a centrifugal resistance operating against the existing unified story. This centrifugal direction defies standard news reports about Peoples Temple and Jonestown, just as it challenges the apostate accounts that focus solely on the dramatic and the sensationalistic. While the centripetal forces of the dominant society have excluded African American perspectives on Jonestown and Peoples Temple, these perspectives are nonetheless exerting pressure by undermining traditional narratives about the group and its demise.

Representations of the events in Jonestown are dialogical and exist within a historical context that is not exhausted by the so-called facts as they have been explicated by historians, the media, and apostates. Bakhtin’s theory of the dialogical nature of literature–and its inevitable inconclusiveness–applies very well to the ways in which people of color have challenged the dominant narratives about Jonestown and Peoples Temple. The remainder of this article briefly surveys some of the scholars, writers, artists, and poets who have re-inscribed blackness into the story of Peoples Temple.

It is important to consider, first of all, how the people of Guyana explained Jonestown, both as a community and as an event. If the African American perspective was erased, the view from Guyana was completely ignored. Writers from Guyana and the Caribbean interpreted Jonestown within the framework of historical colonial relationships between Europe and indigenous societies, including slave economies. Their outlook has never been part of the Jonestown story as told in the United States. As they tell it, the story is about Guyana rather than Jonestown.

One of the very first commentaries to appear after November 18 blamed the government of Guyana for what happened in Jonestown, accusing it of criminal negligence, criminal greed, criminal conspiracy, and criminal arrogance. In his article from November 21, 1978, titled “A State Within A State,” Eusi Kwayana (b. 1925), a long-time political activist in Guyana, presented a list of unanswered questions, asking, among other things, why a town in Guyana would be named after Jim Jones, an American.[26] Kwayana republished this and other essays from Guyanese writers in his 2016 book A New Look at Jonestown.

In a speech delivered at Stanford University in 1979, Dr. Walter Rodney (1942-1980) echoed some of Kwayana’s questions.[27] Rather than ask “Why Jonestown?” the Guyanese activist and intellectual proposed the question “Why Guyana?” He proceeded to examine the social and political factors that made an American expatriate commune so attractive to the developing nation. He pointed out that the relationship between Peoples Temple and the government of Guyana did not flow through ordinary, legislative channels but rather consisted of a series of backroom deals between selected officials and the Americans. Rodney argued that the power structure of Peoples Temple corrupted government officials with material goods in the form of gold, currency, and gems. Further, the group seemed to be immune from police scrutiny, with the ability to bring weapons and drugs into the country.

Rodney concluded his talk by saying that, from the stance of the Guyanese people, Jonestown was a preventable disaster. “We mustn’t get involved in mysticism,” he warned,

which says that this thing is impossible to comprehend; how can human beings do this to themselves and each other. I don’t know the answers to those questions. … [But it could] have been prevented because so many abuses were known to have been occurring over the weeks and the months prior to the final debacle that something would have been done to put a stop to it.

The existence of Jonestown was not in the national interest of Guyana. And the tragedy was preventable, though “if it was to have been prevented, the principal agency in its prevention would have had to be the Guyanese government.” Rodney saw the larger tragedy as belonging to the people of his nation, who were living in a country that was facing unemployment, inflation, violence, unrest, and a host of social problems. His words were prescient, since he was assassinated in a car bomb set by government forces in 1980.

Like Walter Rodney, the novelist Wilson Harris (1921-2018) located Jonestown squarely within Guyana and tied it to the history of South America, with its culture of Mayan sacrifices, colonialism, and postcolonial oppression. In the introduction to his novel, titled Jonestown, he stated that all of the characters in the book are “fictional and archetypal.”[28] This indicated his purpose in placing Jonestown and Jim Jones (who is Jonah Jones in the book) in an enlarged and expansive drama that transcends time and space and yet at the same time is intimately linked to the reality of colonialism in the Guianas–British, French, and Dutch.

Born and raised in Guyana, Sir Theodore Wilson Harris writes dense and rather difficult novels that frequently deal with colonialism in the Caribbean. In Jonestown, he concerns himself with history and memory, especially the gap in the history of precolonial peoples that has been erased due to their extermination. He claims that it is essential to create a jigsaw in which “pasts” and “presents”–as well as likely or unlikely “futures”–are the pieces that multitudes employ in order to bridge chasms in historical memory.[29] Writing not just about Jonestown but about all of the previous loss of life, Harris states that “the lives and limbs of those who have perished need to be weighed as incredible matter-of-fact that defies the limits of realistic discourse.”[30]

Harris rejects traditional novelistic realism in his evocation of the indifference of empire past and present. One of his timeless characters is Carnival Lord Death who mocks justice with his “pitiless barter of the numb word, numb lips, numb ears and eyes.” Harris asks: “What sort of Justice did Carnival Lord Death administer? He was a just man: as just as any man could be in the Mask of Death. What are the foundations of Justice as the twentieth century draws to a close?”[31] We cannot read Jim Jones into the character of Carnival Lord Death or into any of the figures Harris draws. And yet we cannot read Jones apart from that character either. Life and meaning are greater than Jonestown; nevertheless, Jonestown makes up that life and that meaning in a postcolonial context.

The novel Children of Paradise, by Guyanese poet Fred D’Aguiar, is indebted to Harris’s earlier one. Though it follows a more traditional narrative structure, it still depends on magical realism, as does Harris’s. For example, one of its main characters is an intelligent gorilla named Adam. D’Aguiar’s novel is not literally about Jonestown, in that he depicts a fundamentalist religious commune–far from what existed in Jonestown. And while the novel alludes to race, this is not central to D’Aguiar’s story. As the author acknowledges, his book “is a novel inspired by Jonestown rather than in strict adherence to it.”[32] Instead of being about Jonestown, then, it is a type of meditation on childhood, totalitarianism, and Guyana. Like other writers from Guyana, D’Aguiar depicts his country’s officials as particularly culpable for the disaster. Time and again his book shows the venality of government agents who receive bribes, ignore complaints, and protect the criminal activities of the People’s Commune, as it’s called in the novel. Jonestown is really about Guyana, in his view, rather than America.

D’Aguiar’s earlier collection of poems, titled Bill of Rights, presents a much more explicit response to Jonestown.[33] The poems reflect the “cross-culturalities” of Guyana, with references to Tom and Jerry (the United States), Whitbread and Brixton (the United Kingdom), and Banks Beer (Guyana).[34] D’Aguiar puts Jonestown within the context of the surge and flow of immigrants across continents, always demonstrating an awareness of the legacy of domination, whether by colonialists or by Jim Jones.

I see stars you see wounds in that flag

I see red you see blood

I see sky you see blue

I see black you see white

I see stripes you see bars.[35]

The poems present oppression and domination as global problems. What happens in Guyana happens around the world. Is a bill of rights needed, D’Aguiar asks,

A Bill of Rights for the Front Line

As much as for the boys from the Blackstuff,

For Glasgow’s tenement

Blocks and the Shankhill Road,

for Tiger Bay and Millwall’s Den?

A Bill of Rights, we vowed before the outing

Of our lights.[36]

The poems weave Jonestown into a song of protest. They criticize Jim Jones, who “doesn’t know his okra/From his bora/His guava from his sapodilla/His stinking-toe from his tamarind.” Yet the deaths in Jonestown are larger than one man or one place, according to the poet. Listing the rivers of Guyana and the Georgetown airport, Timehri, D’Aguiar links Jonestown inextricably to Guyana and its precolonial past:

These are bodies lying on mud floors

In huts; on the grass; around dead fires;

In the final embraces throughout

The neat wooden walkways;

On every clearing; and from now on

By the banks of the Potaro, the Mazaruni,

Essequibo, Corentyne, Demerara.

At Timehri. Quetzalcoatl,

Tell me this is not so.

This is poetry that puts an entirely different spin on what happened in Jonestown. We see it not as an isolated instance but as part of a larger project of oppression and subjugation of all people of color.

In contrast, Michael Gilkes’ book, Joanstown and Other Poems, reminds us that Guyana is much more than the Jonestown tragedy that occurred there in 1978. (The book is named after his wife, Joan). Some twenty poems evoke Guyana’s natural history, its precolonial past, life under colonial rule, and the present. Indeed, the very title “Joanstown” indicates that Gilkes plans to present the antithesis of the other “Jonestown” in a celebration of all that makes his nation beautiful, memorable, and beloved. The poet treats Jonestown as an anomaly, something apart from and unrelated to Guyana’s past or present: Guyana is not Jonestown, nor is Jonestown Guyana.

Jan Carew’s poetic essay (or short story) “Jonestown Revisited” appeared in Eusi Kwayana’s 2016 edited collection.[37] Like Walter Rodney and Eusi Kwayana, Carew (1920-2012) was active in Guyana’s independence movement. In “Jonestown Revisited,” the narrator travels to Jonestown with his great uncle, a Carib Indian named Kalinyas. Like the works I’ve been describing, the story places Jonestown within the framework of Caribbean history. As they tour the ruins in the decaying jungle, Kalinyas fiercely tells the narrator: “You must write our truth.” He continues, “They wrote so many words about Jonestown! Those Yankee-people are strange. When they travel they want to carry the whole of their country on their backs. But look around you. Can you see how everything they left behind them is vanishing.” Kalinyas observes that the Americans came without wanting to know the history of either the Caribs or of the land. “This is a holy place for us,” he tells his great nephew, “and no strangers have ever been able to stay here for long without making peace with our ancestors.” And then he reiterates: “They wrote so many words about Jonestown … but they wrote them about themselves. For them we were invisible.”

Finally, Shiva Naipaul’s (1945-1985) 1980 study of Jonestown, titled Journey to Nowhere in the United States, but called Black and White in the United Kingdom, laid the blame for Jonestown squarely upon the government and people of Guyana.[38] The Trinidad-born novelist, and brother of the more famous V. S. Naipaul, also criticized both American society–for its failure to respond to human need–and California’s culture of self-transformation.

These brief selections reveal how much has been lost through the silencing of voices from Guyana. Wilson Harris’s novel was never published in the United States, nor was Fred D’Aguiar’s book of poetry, though his novel found a mainstream American publisher. Eusi Kwayana’s book came out in a limited edition from a tiny publisher in Los Angeles. But re-inscribing Jonestown within narratives about Guyana and colonialism enlarges our understanding of the past and the present. These works exert a centrifugal pull against the dominant narratives, placing Guyana, rather than the United States, at the center.

Before considering voices from America, I’d like to mention what I think is an important contribution to the discussion–the book Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, published in 2004.[39] In that edited volume, Anthony Pinn, Mary Sawyer and I collected articles by African Americans and others to examine the Temple through the lenses of black experience. It was by no means a definitive treatment, but it was a start.

Turning to writers of color from the United States, we find quite a few poetic treatments. Several women poets have used Jonestown as both code and subject in their poems. Audre Lorde’s (1934-1992) reference to drinking “poisoned grape juice in Jonestown” is part of a larger project in the poem “The Art of Response”–that is, how African Americans have responded to the oppression they have endured.[40] In contrast, Lucille Clifton’s (1936-2010) “1. at jonestown” directly addresses Jonestown from the point of view of an African American follower of Jim Jones who is about to drink the poison:

on a day when i would have believed

anything, i believed that this white man,

stern as my father, neutral in his coupling

as adam, was possibly who he insisted he was.[41]

Pat Parker (1944-1989) devotes a long poem to the problem of Jonestown. In the title work from her fifth book of poetry, Jonestown and Other Madness, Parker repeats the refrain:

Black folks do not commit suicide

Black folks do not

Black folks do not

Black folks do not commit suicide

The poem describes her emotions as she hears the news of the deaths. She captures the carnivalesque atmosphere of the newscasting at the time as the story explodes:

STEP RIGHT UP

STEP RIGHT UP

Ladies and Gentlemen

Have I got a tale

For you

Later in the poem she writes that “the Black people / in Jonestown / did not commit suicide / they were murdered … / in small southern towns / they were murdered in / big northern cities.” She continues by saying they were murdered as school children by teachers who didn’t care, by welfare workers who didn’t care, and by politicians who didn’t care. Thus, she sets Jonestown within the context of the black experience in America. She is convinced that “Black folks do not commit suicide.” A frequent refrain in the poem, it is also the last line.[42]

Two additional black female poets have taken Jonestown as their subject, going beyond the shorthand equation “Jonestown equals evil” and humanizing the people who lived and died there. darlene anita scott’s (b. 1975) poems have been published in a number of literary journals, but her Jonestown collection has been republished on the Alternative Considerations website.[43] The poem “How Today Will Look When It’s History (14 September 1977)” grasps the essence of the complicated family structure that existed in Peoples Temple.

I have two sisters, a brother, and

none of them look like me.

Sometimes I wish they did.

Or, I, like them.

A line from “How Sleep Finds Us (12 February 1977)” suggests the long trajectory toward death:

The path a bee takes toward its sting

is not straight; not planned.

And finally, from “What We Talk About In Our Cottage:”

I. Want

lack; not enough and claiming

more; a need met in tandem:

if all else fails. Because we can’t live without it.

These short selections from Scott’s longer works evoke many different elements of Peoples Temple and Jonestown, thwarting the easy explanations produced by both mainstream society and by African American communities.

Carmen Gillespie (b. 1965) also confounds our assumptions in her book-length collection of poems. Jonestown: A Vexation captures the enigma and paradox of life and death in the community.[44] The book comprises commentary, biography, and history as well as poetry, and, on occasion, incorporates words from Jim Jones’s sermons and speeches. Gillespie begins with poems that point to Guyana’s past, before turning to Jones and to the people in the Temple movement. She identifies the nature of Jones’s power in the poem “1956.”

After years of wanderings

through mazes of back streets

ferreting pentecostal gospel,

the troubadour and the preacher

tapped the source:

Blackness,

a mother load

electric and Voltaic

as oil or coal,

a generator to amplify

their trumpetvoices

to all who would listen.

Joshuas both–unshutting

Jericho–crooning

down doors

and rolling the rocks

away.

Gillespie also includes a series of sketches of Jonestown, with the titles “There, there was music,” “There, there were flowers,” “There, there was loving,” “There, there was color,” “There, there was laughter”–each designed to muddle, or vex, our preconceptions of what it was like in Jonestown.

She dissects the word “vexation” in six sections, corresponding to dictionary definitions of the word. The fourth section, for example, defines vexation as “an entity situation, memory, or place that eludes definition or fixedness.” Certainly this echoes Bakhtin’s belief in the inconclusive nature of interpretation. We remember that it is the desire of the status quo to fix meaning at the expense of ambiguity or alterity. Gillespie’s fifth section makes her poetry a specifically African American resistance to the centripetal forces striving for unity, since vexation is also “a long-standing injustice, the injury of which is suffered as a direct result of another’s duplicity.”

Finally, three books that present the perspective of African American women who were members of Peoples Temple are worth noting. Two are nonfiction first-person accounts and the last is a novel.

An elderly black woman, Hyacinth Thrash (1905-1995), survived the mass deaths simply by being asleep in her cottage. Her story–The Onliest One Alive: Surviving Jonestown, Guyana–explains the appeal the Temple and Jim Jones’s message had for her and her sister Zipporah Edwards.[45] The first third of the book describes her experiences as an African American woman living in the segregated society of Alabama and Indiana. It then turns to their lives in the Temple and in Jonestown as middle-aged black women. Although the book is by turns inaccurate (due to misinformation) and sensational (due to the coauthor), it nevertheless provides fascinating insights into the lives of ordinary, rank-and-file members. For example, Thrash describes what she did during a toilet paper shortage: “Jim did get a shipment of Gideon Bibles in Guyana. But when the toilet paper ran out, he told us to use the leaves of the Bible. But I couldn’t do it! Not God’s Word! I hunted up little pieces of paper and stored up bits of rags to use.”[46] With a bit of humor she describes a White Night, where she was supposed to get up in the middle of the night, get dressed, and rush out of her room. One night she decided to just stay in her cottage. “I said, ‘If they’re going to kill me anyhow, I’ll be here and they can do it here.'”[47] Her staying in bed on the final day probably saved her life.

Leslie Wagner-Wilson (1957) escaped on November 18 with the group that pretended to be heading out for a picnic. She carried her two-year-old son on her back for miles through the jungle. Slavery of Faith describes her life before, during, and after Peoples Temple, giving indications of its ideology and ethos.[48] The daughter of a black woman and a white man, she found the Temple very accepting, at least at first. Jim Jones called her “my little Angela,” after black radical Angela Davis. Then she saw young white recruits advancing into leadership positions ahead of long-standing black members and personally encountered racism in her work assignments in Jonestown. But if life was arduous in the jungle, Wagner-Wilson found it even more difficult in the United States afterwards. She recounts her time as a battered woman, her struggles as a single mother, and her fight to get free of drug addiction. The shame and stigma of Jonestown remained with her until 1997, when she began to write her memoir. No one had known of her connection to Jonestown during those intervening decades.

Many African Americans with ties to the Temple experienced similar humiliation and disgrace, even losing their jobs when employers learned of their background. As a result, they remained deeply closeted for decades regarding the Temple. Their voices were not so much erased as repressed in order to survive.

Finally, in her novel White Nights, Black Paradise, Dr. Sikivu Hutchinson (b. 1969) creates four fictional African American women who represent a spectrum of attitudes toward the Temple and toward Jim Jones.[49] She infuses her book with a black consciousness “to creatively illuminate (and problematize) what is still a turbulent and evolving historical record and signal event in the ‘psychic space’ of African American migrations.”[50] Partly because of her work in the atheist and humanist movements, Hutchinson’s novel focuses on the secular reasons for people joining the Temple, namely the promise of social justice during a time of black activism. Her characters are smart, skeptical, sharp, and drawn to the radical politics of the group. Thus, she re-inscribes black voices into the Jonestown narrative.

With Hutchinson we have come full circle to Bakhtin’s claim that the historical record continues to evolve, despite the best efforts of mainstream society to control it. This is especially true of narratives about Jonestown, given its multiple meanings: Is it a morality play pitting evil against good? A tract on the danger of religious fanaticism? A plot to eliminate black progressives in the San Francisco Bay Area? A mass murder to cover up a CIA hit on a congressman? The centripetal narrative seems to concentrate on the maniacal cult leader and his brainwashed followers. But centrifugal narratives that return black voices and black consciousness to the story take us into many other directions: from racism, toward justice; from colonialism, toward liberation; from white, toward black. Black lives matter when we consider who is telling the story of Jonestown.

Conclusions

What can we conclude from the narratives that re-inscribe blackness into the story of Peoples Temple? They certainly raise the question of the role of African Americans–and more broadly, people of color–within the organization. Were black people simply victims, manipulated by a white charlatan and blindly led to their doom? Were they self-conscious agents, compromising their integrity when they knew things were going wrong? Were they resisters, rebelling in small but effective ways?

Moreover, how is Jonestown relevant for people of color today? We might consider some elements of Peoples Temple–its resource-sharing, its progressive commitments, its social service orientation–worth reclaiming. Certainly many African Americans in the Temple joined, and stayed, because they felt empowered. The members’ lived experience of integration is also something to study closely. Can we look for the ways in which empowerment–and not just disempowerment–occurred?

Nevertheless, erasure is real. It happens and will continue to happen. This means we must be ever vigilant as to the ways in which erasure occurs. We must be proactive in seeking out the untold stories, the forgotten histories, the neglected pathways. This is not just the task of the scholar. It falls to everyone.

At the same time, we have to be careful about essentializing race as we try to reverse the effects of erasure. Certainly racial identity is not a single reified thing. That is pretty much the point that Percival Everett makes in much of his writing. I asked at the beginning of this article, what does it mean to be black? I now add, what does it mean to be white? In an article from 1970 titled “What America Would Be Like Without Blacks,” Ralph Ellison wrote:

Despite his racial difference and social status, something indisputably American about Negroes not only raised doubts about the white man’s value system, but aroused the troubling suspicion that whatever else the true American is, he is also somehow black.[51]

Just as African Americans are “bathed from birth in the deep and nourishing waters of African-American folkways, so too are all Americans. That idea is the cause for which Ralph Ellison gave the last full measure of his devotion,” according to his biographers.[52] Ellison’s vision seems to avoid the twin problems of essentialism and erasure.

We will always be walking a fine line between erasing people and their histories and essentializing the identities of those same people. This paper has suggested some directions out of this dilemma in regard to narratives about Peoples Temple and Jonestown–namely by recognizing and celebrating the voices that had once been silenced. As long as we remain in dialogue, we can transcend the forces that lead to erasure.

This article is an expansion and revision of a lecture given at The Griot Institute at Bucknell University on January 31, 2018.

Notes

[1] Catherine Prendergast, “The Absent Presence in Composition Studies,” College Composition and Communication 50, no. 1 (September 1998): 36-53.

[2] Mary Hawkesworth, “From Constitutive Outside to the Politics of Extinction: Critical Race Theory, Feminist Theory, and Political Theory,” Political Research Quarterly 63, no. 3 (September 2010): 686-96.

[3] Richard Delgado, “The Imperial Scholar: Reflections on a Review of Civil Rights Literature,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 132, no. 3 (March 1984): 561-78.

[4] Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (New York: Vintage International, 1980), 439.

[5] Percival Everett, erasure (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2011).

[6] Ellison, Invisible Man, 303.

[7] Was it Murder or Suicide: A Forum, the jonestown report 8 (2006), .

[8] These articles were reprinted in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary Sawyer (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004).

[9] Clayton’s account appears in Kenneth Wooden, The Children of Jonestown (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981). Rhodes’s story is told by Ethan Feinsod, Awake in a Nightmare: Jonestown: The Only Eyewitness Account (New York: W. W. Norton, 1981).

[10] Phil Blakey, Richard Janaro, Helen Swinney, and Charles Touchette were on the Albatross; Herbert Newell and Clifford Gieg were aboard the Cudjoe.

[11] The Julius Evans family (five people), the Leslie Wilson family (two people), Richard Clark, Robert Paul, Johnny Franklin, and Diane Louie.

[12] Leslie Wagner-Wilson, panel discussion, “Black Women, Peoples Temple, and Jonestown,” Museum of the African Diaspora, San Francisco, July 29, 2017. Philip Zimbardo calls Clark a “Jonestown hero,” who “was like a black Moses leading some of his people out of Hell.” Zimbardo, Jonestown Heroes, the jonestown report 10 (October 2008), .

[13] Annotated Transcript 1021-A, Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, Department of Religious Studies, San Diego State University, accessed January 31, 2018.

[14] Q 987 Transcript, Alternative Considerations, accessed January 31, 2018.

[15] Don Beck, Administration, Alternative Considerations, accessed 31 January 2018.

[16] Don Beck, Jobs in Jonestown by Department, Alternative Considerations, accessed January 31, 2018.

[17] Lear K. Matthews and George K. Danns, “Communities and Development in Guyana: A Neglected Dimension in Nation Building” (Georgetown, Guyana: University of Guyana, 1980); reprinted as “The Jonestown Plantation” in Eusi Kwayana, A New Look at Jonestown: Dimensions from a Guyanese Perspective (Los Angeles: Carib House, 2016), 82-95.

[18] Matthews and Danns, “The Jonestown Plantation,” 89.

[19] Matthews and Danns, “The Jonestown Plantation.”

[20] Rebecca Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, et al., 57-80. For more recent demographic statistics, see Rebecca Moore, An Update on the Demographics of Jonestown, the jonestown report 19 (2017).

[21] For a negative answer, see Monroe H. Little Jr., “Review of Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America,” Indiana Magazine of History 102, no. 4 (December 2006): 392-93.

[22] M. M. Bakhtin, “Discourse in the Novel,” in The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. Michael Holquist, trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 270.

[23] Bakhtin, “Discourse in the Novel,” 271.

[24] Bakhtin, “Discourse in the Novel,” 276.

[25] Bakhtin, “Discourse in the Novel,” 276.

[26] Eusi Kwayana, “A State Within A State,” in Kwayana, A New Look at Jonestown, 146-54.

[27] Walter Rodney, Jonestown: A Caribbean or Guyanese Perspective, Alternative Considerations, accessed January 31, 2018; reprinted from Kwayana, A New Look at Jonestown, 113-36.

[28] Wilson Harris, Jonestown (London: Faber and Faber, 1996), 3.

[29] Harris, Jonestown, 5.

[30] Harris, Jonestown, 82.

[31] Harris, Jonestown, 70.

[32] Fred D’Aguiar, Children of Paradise (New York: HarperCollins, 2014), 363.

[33] Fred D’Aguiar, Bill of Rights (London: Chatto and Windus, 1998).

[34] The term “cross-culturalities” comes from Wilson Harris. Marina Camboni and Marco Fazzini, “An Interview with Wilson Harris in Macerata,” in Resisting Alterities: Wilson Harris and Other Avatars of Otherness, ed. Marco Fazzini (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2004), 57.

[35] D’Aguiar, Bill of Rights, 69; italics in original.

[36] D’Aguiar, Bill of Rights, 79.

[37] Jan Carew, Jonestown Revisited, Alternative Considerations, accessed 31 January 2018; reprinted from Kwayana, A New Look at Jonestown, 137-44.

[38] Shiva Naipaul, Journey to Nowhere: A New World Tragedy (New York: Penguin Books, 1980).

[39] Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, eds., Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004).

[40] Audre Lorde, The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000).

[41] Lucille Clifton, “1. at jonestown,” in Next: New Poems (Brockport, NY: Continuum, 1989).

[42] Pat Parker, “Jonestown,” in Jonestown and Other Madness (Ithaca, NY: Firebrand Books, 1985).

[43] darlene anita scott, Poetry by darlene anita scott, Alternative Considerations, accessed January 31, 2018.

[44] Carmen Gillespie, Jonestown: A Vexation (Detroit: Lotus Press, 2011).

[45] Catherine (Hyacinth) Thrash, as told to Marian K. Towne, The Onliest One Alive: Surviving Jonestown, Guyana (Indianapolis: Marian K. Towne, 1995).

[46] Thrash, The Onliest One Alive, 104.

[47] Thrash, The Onliest One Alive, 98.

[48] Leslie Wagner-Wilson, Slavery of Faith (Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 2008).

[49] Sikivu Hutchinson, White Nights, Black Paradise (Los Angeles: Infidel Press, 2015).

[50] Hutchinson, “Author’s Note,” White Nights, Black Paradise, 323. As of this writing, Hutchinson is developing her novel into a full-length drama.

[51] Ralph Ellison, “What America Would Be Like Without Blacks,” Time, April 6, 1970, accessed January 31, 2018.

[52] Maryemma Graham and Jeffery Dwayne Mack, “Ralph Ellison, 1913-1994: A Brief Biography,” in A Historical Guide to Ralph Ellison, ed. Steven C. Tracy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 52.

Copyright: COPYRIGHT 2018 Communal Studies Association