(Editor’s note: This article is republished courtesy of MLive.com. The original article appears here.)

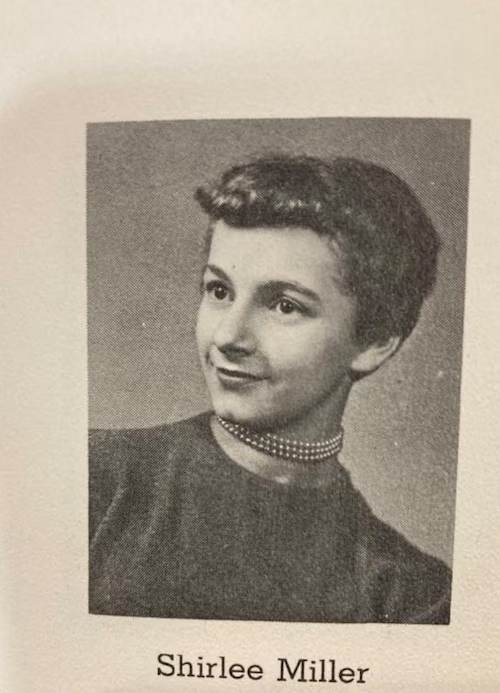

(MLive.com editor’s note: This is the second installment of a five-part series on the life of Bay City native Shirlee A. Fields (nee Miller), who was among 918 people who died in a mass murder-suicide in Jonestown and other Guyana locations on Nov. 18, 1978.)

BAY CITY, MI — In the years before Bay City native Shirlee A. Fields departed the U.S. for Jonestown, Guyana, a place from which she would never return, she and her family lived in California. While there, she would cross paths with the Rev. Jim Jones, joining his growing congregation in the Peoples Temple.

Shirlee and Donald Fields befriended the Harrison family, including their children, daughter Lori and son Mark, who attended third grade with their son.

Bob Harrison in 2013 posted his recollections of the family on Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, which documents those who were part of the Nov. 18, 1978, mass death led by the Rev. Jim Jones. Harrison, who has since died, wrote he and his wife often dined with the Fields family.

“As conversations go, Shirley was the more outgoing of the two, very talkative, with a quick mind and an active imagination,” Harrison wrote. “We enjoyed their company; they were intelligent and interesting, and fun to be with.”

Shirlee, however, had frequent bouts of pessimism, Harrison wrote. As with many who gravitated toward Jones and his message, she expressed cynicism over the state of the world and the social ills plaguing it.

“Our failure as a society to end poverty and racial injustice rankled her,” Harrison wrote. “She often talked of her hope to find a belief which offered spiritual truth and present-world justice, and it was not long until she found the religion for which she had been searching.”

More than once, Shirlee stated her intent to get passports for her family “in case they begin to persecute Jews here in the United States,” Harrison wrote.

The Fieldses grew less available in 1976. They talked of taking a special bus to San Francisco on weekends for meetings. At the time, Peoples Temple was headquartered there.

When the Harrisons expressed curiosity, Shirlee enthusiastically told them of Peoples Temple, a new religious group she’d discovered. Her husband was supportive but more reserved.

“It was our belief that this new religion was Shirley’s ‘thing’ and Don was just going along to keep her happy,” Harrison wrote. “This was in keeping with their style: Shirley took the initiative, and Don supported her.”

Exactly when and under what circumstances Shirlee first encountered Jones is unknown.

Soon, the family was absent every weekend and also grew increasingly secretive. When the Harrisons asked them about Peoples Temple, they gave vague responses.

“She did tell us the members were very diverse, and were from a wide range of ages, ethnic backgrounds, cultures, educational levels and economic groups,” Harrison continued. “They all prayed and wanted to end poverty and social injustice.”

In the winter of 1976, the Fieldses moved to San Francisco. They sold their house, vehicles, and property, giving away whatever they could not sell. They told the Harrisons they were giving their money to Peoples Temple and would live in housing the group provided.

By January 1977, the family was active enough in Peoples Temple for their then 9-year-old son Mark to march in protest of lower-income residents being evicted from San Francisco’s International Hotel.

The Harrisons again met with the Fieldses a handful of times in spring 1977. When they asked about their situation, they clammed up.

“They had apparently all been instructed to avoid discussing Peoples Temple with outsiders,” Harrison wrote.

The Fieldses lived in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Northridge before entering Guyana on July 23, 1977. Just days after her arrival, Shirlee signed her name to several affidavits as a witness to Jones’ “miraculous capabilities.”

When the Harrisons heard of the Jonestown Massacre, the mass suicide resulting in 918 deaths, they intrinsically knew the Fieldses were present.

“My wife was very angry that Shirley and Don had apparently taken the children to their doom,” Harrison wrote.

Shirlee Fields was one of eight Michiganders to die in Jonestown. The others include Jeffrey J. Carey of Flint, the Hicks family of four from Detroit, and Barbara J. Cordelland Mary Beth Wotherspoon of Grand Rapids. In the case of Wotherspoon, her sister H.J. Jones earlier this year published a book on her sister titled “Jonestown: An American Family Tragedy.”

Who were Peoples Temple?

Jones founded Peoples Temple in Indianapolis in 1954, emphasizing racial and class equality. He left the possessive apostrophe out of his church’s name to signal its inclusivity and rejection of material ownership.

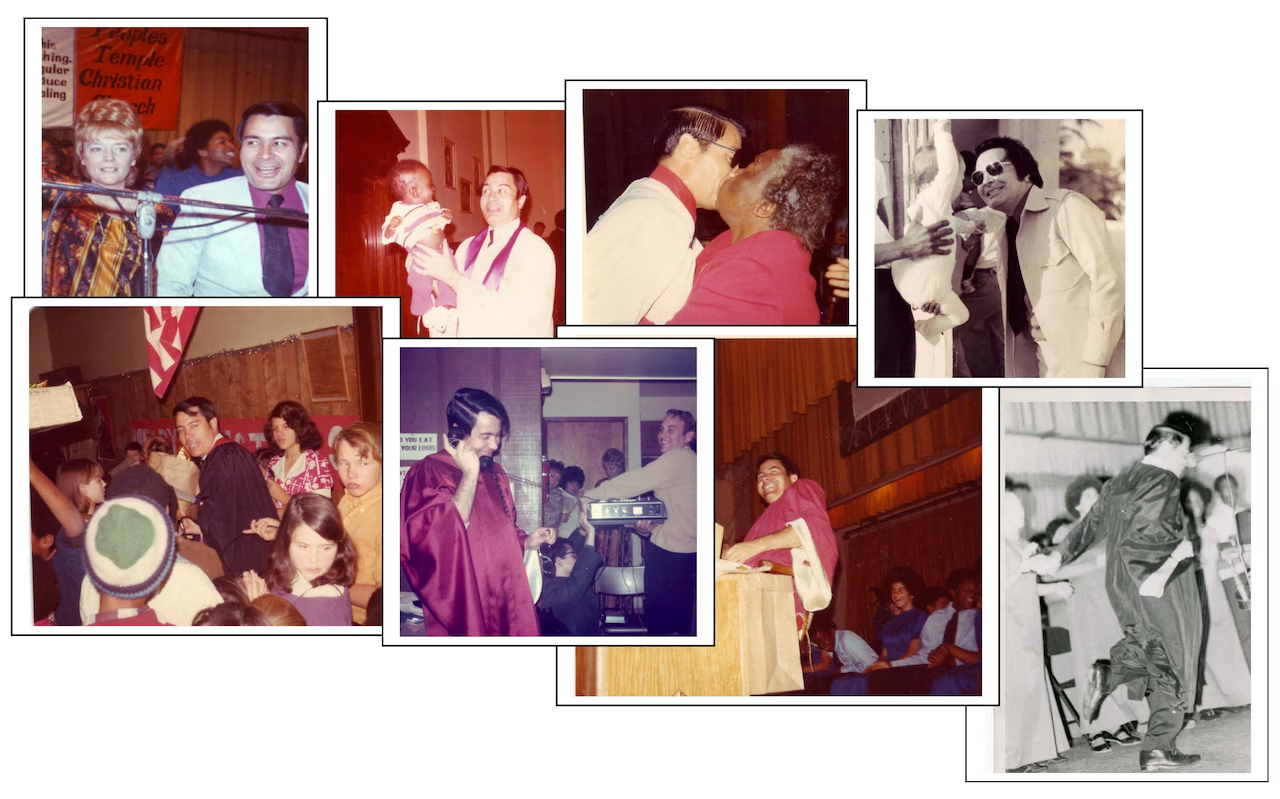

Jones’ impassioned sermons, theatrical stage presence, and faith healings merged elements from different Christian denominations. To practice what he preached, Jones and his wife Marceline adopted several children of different ethnic backgrounds, a professed “rainbow family.”

In time, the Temple’s congregation grew to be 80-90% Black.

“If he had not moved to California and Guyana, he would be considered one of the Civil Rights leaders of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s in the Midwest, doing what he did in Indianapolis,” said researcher Fielding M. “Mac” McGehee III, a leading authority on Jonestown.

Jones’ son, Stephan G. Jones, is less on board with that assessment.

“I think part of him genuinely cared about social justice,” he said, speaking with MLive. “Even then, there was a selfish component to that. I think he was more caught up in appearing as a great Civil Rights leader than actually being one.”

As years progressed, Jones moved his flock to California.

The church’s philanthropy provided legal services, medical care, drug rehabilitation, housing for the disabled, college tuition, and a subsidized cafeteria where anyone could eat for free. With a fleet of Greyhound buses, Jones led congregants on cross-country tours, hosting revivals to recruit and fundraise.

“It was the ‘70s,” McGehee said. “People went out, trying to make the world better.”

As the church evolved, Jones shed much of its Christian theology. At various times, he espoused beliefs in reincarnation, that he could resurrect the dead, and that he was the incarnation of God. He would also describe himself as an atheist or agnostic, preaching an ideology he dubbed “apostolic socialism.”

While the poor and needy continued to join, the church’s ranks were augmented by educated professionals, including professors, engineers, and attorneys.

“They could see the people they were helping,” McGehee said. “(Jim Jones) would say, ‘Your churches keep telling you that when you die and go to heaven, you’ll get your reward. We’re telling you, you can get it here and now.’”

Shirlee’s civic-mindedness likely moved her to join.

“That’s what drove a lot of people like the Fields family, like my wife’s family, and any number of examples I could give,” said McGehee, who had two sisters-in-law join Peoples Temple. “They felt they were doing a service for the world at large and getting that kind of benefit from it themselves.”

Jones grew affluent off the contributions of his parishioners. Despite being married, he was having sex with numerous congregants. For his faithful to attain Jones’ forgiveness for their sins, they would often undergo severe beatings and humiliation, according to recovered documents and survivors’ accounts.

“I was filled with rage at what I saw behind the curtain,” said Jones’ son, Stephan G. Jones. “I saw my father’s antics from a very early age.”

Though Jones curried favor with California politicians and elites, even being named head of the San Francisco Housing Commission, he attracted scrutiny when former church members started alleging abuse and misconduct. Still, he and his organization weathered the storm caused by the 1972 publication of a multi-part exposé in The San Francisco Examiner.

Fearing prying eyes, Jones in 1974 sent his first batch of Temple members to Guyana to begin transforming 3,852 acres of wild brush into an agricultural town.

The settlement grew to include crops, cottages, dormitories, a bakery, a sawmill, a brick factory, an infirmary, a pharmacy, a nursery, an animal shelter, a playground, a radio room, education tents, and a large pavilion. Residents rode horses and raised chickens, cows, and pigs.

Another article in the August 1977 issue of New West magazine outlined physical, sexual, and emotional abuse within the church. The article also called for investigations into the Temple allegedly skimming funds from care homes they operated for troubled children and the elderly.

Two months before the article published, Jones left the U.S. for Guyana in June 1977. The Fields family of four followed him the next month. Jones was also motivated by a custody dispute involving a former member with whom he claimed to have fathered a son. Jones had the boy moved to Jonestown.

“We wanted to believe that finally, we were going to live our dream and have the community we hoped for in greater society,” said Stephan Jones.

Upon arrival, residents’ passports were confiscated. Jones controlled the flow of all news and communication. Miles of dense forest surrounded them, concealing venomous snakes, anacondas, and jaguars. With armed guards loyal to Jones, residents had virtually no means of escape. The nearest settlement was the tiny village of Port Kaituma, six miles away.

Some survivors have said their time in Jonestown was the high point of their lives, espousing the communal love that pervaded. Others have described Jonestown as closer to a forced labor camp, with marathon work shifts in oppressive heat, food shortages, and sadistic punishments.

His mind warped by amphetamines and sedatives, Jones ruled as a mad tyrant, ranting and raving on a public address system at all hours and depriving his exhausted followers of sleep, according to Jeff Guinn’s 2018 book “The Road to Jonestown.”

Most ominously, he amped up a practice he started in the U.S. — compelling his flock to engage in dress rehearsals for a crisis called “White Nights.” The drills often ended in scenarios of mass death, according to The Jonestown Institute.

“It was an anxiety-ridden community after the White Nights began,” Stephan Jones said.

(Cole Waterman is a Michigan-based crime reporter with a long-held interest in Peoples Temple and Jonestown who has submitted numerous primary source transcripts from the FBI’s FOIA files to the site beginning in the fall of 2023. He can be reached at Cole_Waterman@mlive.com.)