In the summer of 2023, I was blessed to be a part of a research trip which lasted just under a week inside the archives of the California Historical Society, exploring the Peoples Temple Collection and the thousands of documents meticulously preserved and arranged by the dedicated staff. The relatively humble exterior of the CHS belied the wealth of information contained within its walls, and even after a week I knew I had barely scratched the surface. Having had some time to reflect on my visit, the sources I found, and the people I met, I thought I would try to describe an experience which I would consider invaluable in the growth of any historian.

My visit to the CHS was not only my first experience of San Francisco, but also my first experience in an archive. I spent five days oscillating between archival study and exploration, combing through carefully preserved and organised materials on the one hand, and piecing together a sense of San Francisco – and Peoples Temple’s place within it – on the other. It was a trip which culminated, for me, in a real sense of lived history and locality. From the Temple’s former church on Geary (long since replaced by a post office) to the various communal apartments dotted in and around the Fillmore, the geography of the Temple’s life in San Francisco became increasingly tangible to an English – and not particularly well-travelled – historian.

In fact, in many ways, San Francisco reminded me of London. In both cities immense corporate wealth often stands shoulder-to-shoulder with residential poverty and deprivation; well-funded business and commercial districts are but a stone’s throw away from homelessness, impoverishment, and crime. Living in one of London’s poorest boroughs next to one of its most expensive and grotesque shopping centres, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of familiarity as I wandered around San Francisco. It was not hard to see, even 45 years after Jonestown, why Peoples Temple had attracted so many people to what appeared to be an organisation offering genuine solutions to community problems.

For all the dramatics and outright lies which Jones had preached to his audiences – ranging from concentration camps under the fictional King Alfred Plan to ethnic bioweapons and nuclear Armageddon – when he spoke about poverty, the death of community, the dilapidation of residential neighbourhoods and inequitable economics, he pierced the hearts of those who lived and breathed their observable reality surrounding them. In many ways, I could still see this reality, long after Peoples Temple had drifted into the realm of history and (all too often) myth. I wondered if the universality of urban living, and the critiques of urban life which come with it, acted as a mortar which held the diverse members of Peoples Temple together; Christian, communard, and activist alike could realise the truth of many of the Temple’s less dramatic or inflammatory critiques of modern life.

Most of my time within the California Historical Society was spent combing through the Temple’s mass-mailers: newspapers, pamphlets, periodicals, and solicitations targeting San Francisco, Los Angeles, and areas further afield. I had the opportunity to examine some of the realia produced in California as well as Guyana; from broaches and religious paraphernalia in the former, to children’s toys lovingly crafted in the latter. These items, many of which have been described by researchers over the years, took on a very different character when when I actually held them in my hands, and felt the time, effort, and care that went into producing them. Much the same can be said of the periodicals and mass-mailers described above: they were produced with increasing sophistication and levels of media and design literacy, with a recognisably human touch found in occasionally humorous articles and editorial levity.

Most of my time within the California Historical Society was spent combing through the Temple’s mass-mailers: newspapers, pamphlets, periodicals, and solicitations targeting San Francisco, Los Angeles, and areas further afield. I had the opportunity to examine some of the realia produced in California as well as Guyana; from broaches and religious paraphernalia in the former, to children’s toys lovingly crafted in the latter. These items, many of which have been described by researchers over the years, took on a very different character when when I actually held them in my hands, and felt the time, effort, and care that went into producing them. Much the same can be said of the periodicals and mass-mailers described above: they were produced with increasing sophistication and levels of media and design literacy, with a recognisably human touch found in occasionally humorous articles and editorial levity.

The Temple’s mass-mailers and newsletters, archived in the Ephemera and Publications Collection at the CHS, occupied much of my time because they fascinated me as textual objects and marketing materials. My interest as an historian focuses on the emotions of the past, and publications such as newspapers and mass-mailers are fantastic sources for examining the priority of certain emotions in any given institution. They represent efforts in framing, in processing news and events in a way which is congruent with the worldview and ideology of the institution which produces them.

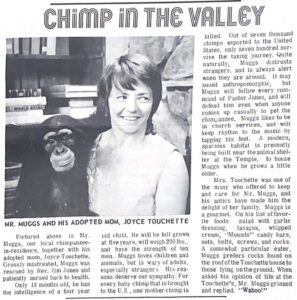

To provide a brief example – but one that has occupied my thoughts long after my return to England – is the difference in tone between an early Temple publication, The Temple Reporter, and its later iteration, the Peoples Forum. The first issue of the Reporter, published in the summer of 1973, has all the trappings of a community newsletter. Articles detail Temple volunteer work and developments in the local welfare, education, and rehabilitation sectors. It even features a light-hearted character profile of the Temple’s resident chimpanzee, Mr Muggs. The main body of the publication is relatively “feel-good”, with the newsletter described as a “community service”.[1]

To provide a brief example – but one that has occupied my thoughts long after my return to England – is the difference in tone between an early Temple publication, The Temple Reporter, and its later iteration, the Peoples Forum. The first issue of the Reporter, published in the summer of 1973, has all the trappings of a community newsletter. Articles detail Temple volunteer work and developments in the local welfare, education, and rehabilitation sectors. It even features a light-hearted character profile of the Temple’s resident chimpanzee, Mr Muggs. The main body of the publication is relatively “feel-good”, with the newsletter described as a “community service”.[1]

In contrast, the tone of the January 1977 issue of Peoples Forum (Vol. 1, No. 14) is quite dramatic. A cover story on “local Nazis” includes the image of a piece of hate mail allegedly sent to the Temple. Flanking this image is the Temple’s response, as well as other headlines such as “Hate Calls”, “Germ Warfare: In Our Own Backyard”, and “Teenage Suicide”.[2]

In contrast, the tone of the January 1977 issue of Peoples Forum (Vol. 1, No. 14) is quite dramatic. A cover story on “local Nazis” includes the image of a piece of hate mail allegedly sent to the Temple. Flanking this image is the Temple’s response, as well as other headlines such as “Hate Calls”, “Germ Warfare: In Our Own Backyard”, and “Teenage Suicide”.[2]

The difference in emotional tone evident in these two publications is clear. But it is worth questioning whether this reflected a genuine fear among the community (at least those involved with the Publications department and related contributors), or if this was, perhaps, a marketing strategy intended to generate greater solicitations, engagement, and membership within the organisation. After all, we know that discourses of fear are remarkably prevalent across modern news and print media networks, who use fear “to provide entertaining news”.[3] Why would Peoples Temple have been any different?

Within another collection at the CHS, I was intrigued to find a letter written by a woman who was not a member of Peoples Temple but had read the above January 1977 issue of Peoples Forum whilst waiting in her doctor’s reception. It reads, in part, as follows:

Dear Pastor Jones:

I used to hear your radio broadcast over KFAX very early in the morning a few years ago and felt that your program was very worthwhile. Today, in my doctor’s office, I found a copy of your publication, “Peoples Forum.”

Although I think the public should be well-informed as to what is taking place, I question the propriety of using such bold headlines and photographs, which, it appears to me, may have just the opposite effect your paper is attempting to do…

In your Jan. 1, Issue No., 14, Vol. 1, I dare say I would rather have welcomed a picture of Dr. Martin Luther King on your front page, and relegated your lead front page item (Local Nazis) to the back page, where it belongs, for Heaven’s Sake.…

I think, in conclusion, that your paper should be so filled with Good News and the marvelous courage and hope shining out of dedicated Christian lives, as to have little room left or stories of brutality. If tortures must be displayed, to enlighten dedicated Christians, we are poor indeed.[4]

The shift away from positive news stories and towards discourses of fear, I was somewhat pleased to see, was not a product (entirely) of my own eye or biases. Here was a non-affiliated San Franciscan articulating, in her own words, a criticism of the Peoples Forum’s editorial emphases. From my perspective, the change in tone between 1973 and 1977 reflects the shifting strategies of the Temple’s marketing efforts, as well as the reality that fear was an increasingly prominent tool within the institution. Clearly, this was a development which even external contemporaries could observe. As historical documents these publications demonstrate the ways the Temple’s marketing efforts reflected its changing internal emotional logic, intrinsically bound amidst the conflicts and tensions the Temple became embroiled within. Organisations, much like the people who compose them, have a tendency to change over time. After all, nobody joins a cult.[5]

Towards the end of my trip, I was able to visit Evergreen Cemetery – the site of the Peoples Temple memorial and the final resting place of 409 unidentified and unclaimed bodies – and pay my respects in person to those who died on November 18, 1978. This particular experience was something of a watershed moment for me. I made sure to read each name inscribed on the four large granite plaques, encountering many familiar names and many more unfamiliar ones. It was a humbling, powerful experience, made all the more so by the atmosphere of tranquillity and the opportunity for reflection that such peacefulness affords. It is easy for historians – or any social scientists, for that matter – to become detached from the subjects of our study, despite our best efforts. People can become reduced to names on pages, faces can be forgotten in crowds. Although I recognised many names, I was equally touched by those I did not. We know so much about the people of Peoples Temple, yet simultaneously so little; for every person who exists in the documentary record in depth, a dozen are mentioned once or only in passing. Many continue to exist primarily as granite inscriptions, their stories lost or simply yet to be told.

This is why the archival work conducted by the California Historical Society is so important. Although many primary sources from Peoples Temple’s history were burned or lost immediately following November 1978, what remains are powerful testaments to the individuality, creativity, and passions of the people who comprised the Temple. From worship calendars, to handwritten letters, to sophisticated mailers and even handcrafted goods, the variety of material preserved at the CHS lends a tangibility to Temple history which simply cannot be read from a page. The sheer volume of materials, too, means that it will continue to be a vital resource for any study of Peoples Temple, one that contributes to an understanding of the Temple’s life as it was, and not how we may think it to have been. Additionally, the collection reminds us that Peoples Temple was an important part of San Francisco’s history; and understanding the Temple requires understanding its most influential locale, and the relationship of the movement to the space that it once occupied and eventually sought to escape.

This Californian excursion of mine would not have been possible, first and foremost, without the assistance of Fielding McGehee, who was invaluable in planning and orienting my activities for the duration of my stay. Equally, Frances Kaplan and the staff at the California Historical Society went above and beyond what I could have expected in accommodating my research and heaving weighty boxes of documents to me for my leisurely perusal. Thanks to their efforts, my first archival visit was a resounding success. Furthermore, a number of former Temple members extended to me a warmth and kindness that I could not have asked for. Eugene Smith acted as tour guide, driving my cohort around the Temple’s former properties and local haunts (as well as insisting we try his favourite Russian Bakery, which made exceptional blintzes). Jordan Vilchez opened her home to me, providing me with bed, board, and a cooked breakfast that would rival many I’ve had in England (the home of the fry-up). Mike Cartmell, Stephan Jones, Grace Stoen, and Jim Randolph spoke with me at length, courteously and insightfully answering questions that I was sure they had been asked thousands of times before.

I cannot express my gratitude enough for such an opportunity, and I know that it won’t be long before I return. Despite five days of rigorous research, I have much unfinished business left within the Peoples Temple Collection. As time moves forward, and as fewer survivors remain to tell their stories, archival sources such as the CHS and Alternative Considerations digital archive will only become increasingly vital to any well-reasoned, compassionate, and careful study of Peoples Temple. To be sure, there remains much work to be done by those willing to hear the voices of Peoples Temple and Jonestown.

Notes

[1] The Temple Reporter, Vol. 1 No. 1 (Summer, 1973). Peoples Temple Ephemera and Publications, MS 4124, Box 2, Folder 2, California Historical Society.

[2] Peoples Forum Vol. 1, No. 14 (January 1977). Peoples Temple Ephemera and Publications MS 4124, Box 2, Folder 1, California Historical Society.

[3] David Altheide and R. Sam Michalowski, “Fear in the News: a Discourse of Control”, The Sociological Quarterly, Vol. 40 No. 3 (Summer 1999) pp. 475-503.

[4] Letter from Mrs. Suzanne B. Nugent (February 8, 1977). Peoples Temple Records, MS3800, Box 77, Folder 1199.

[5] Deborah Layton in Stanley Nelson’s 2006 Documentary, Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple. “Nobody joins a cult. Nobody joins something they think’s gonna hurt them. You join a religious organization, you join a political movement, and you join with people that you really like.”

(Originating from Chatham, Kent, and now living in London, UK, Connor Ashley Clayton holds an MA in Modern History from from The University of Warwick, and a PhD from Queen Mary University of London. He is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. His complete collection of articles for this site is here. He can be reached at connorclayton96@gmail.com.)