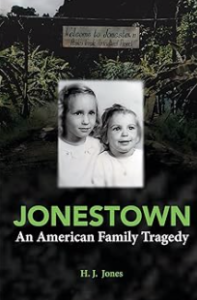

Mary Wotherspoon, her husband Peter, and their child Mary Margaret perished on November 18, 1978 in Jonestown. In this thoroughly researched, thoughtful and moving book, Mary’s sister H.J. Jones takes the reader on a journey of discovery, sharing her own difficult voyage into “one of the wildest places on earth,” the jungle surrounding Jonestown, Guyana. She explores the often brutal facts of the story and delves into the grief it brought to her family and herself. This is a courageous and generous book, uplifting in surprising ways, despite the horrific tragedy at its center: the deaths of 918 people, half of them in their twenties or younger, one-third of them children like the author’s eight-year-old niece.

Mary Wotherspoon, her husband Peter, and their child Mary Margaret perished on November 18, 1978 in Jonestown. In this thoroughly researched, thoughtful and moving book, Mary’s sister H.J. Jones takes the reader on a journey of discovery, sharing her own difficult voyage into “one of the wildest places on earth,” the jungle surrounding Jonestown, Guyana. She explores the often brutal facts of the story and delves into the grief it brought to her family and herself. This is a courageous and generous book, uplifting in surprising ways, despite the horrific tragedy at its center: the deaths of 918 people, half of them in their twenties or younger, one-third of them children like the author’s eight-year-old niece.

Jonestown: An American Family Tragedy begins with a brief history of the author’s family including their parents’ romantic meeting, their marriage and their six children. The author was six, her sister Mary four, and their younger brother two when the father, ravaged with cancer, died “at a psychiatric hospital, locked inside a secure room, driven mad with unmitigated pain.” Herm – at age 15 the oldest son still at home – had been given the job of caring for his father all night, so their mother could get at least some respite.

The death left the family scarred. Their mother changed from a “quiet, reassuring presence” in their lives to one who scolded and punished them and demanded that H.J. must not say “anything about ‘daddy.’” The family church, “a stern Calvinist denomination where people neither laughed nor cried during its austere services,” was no help. The author describes “our mother’s flight from grief” and the ensuing difficulties the children endured as they entered adulthood.

Mary had dropped out of college. Then she found a life partner in Peter, whom the author describes as having “a dazzling intellect,” as well as being “likeable and “unpretentious.” He had been in the Peace Corps and was involved in opposition to the Vietnam War. Mary had joined the protest movement too – the two met in the streets of Chicago in 1968 during the Democratic National Convention – and were soon married with a new baby.

As Mary wrote to her sister:

I’m searching, desperately, for a concrete knowledge of God which I can hold on to, which will bring me above the bad things around me. I’m afraid that life will crack me up before I find what I am looking for. I want to be happy and make others happy.

It was Peter who discovered Peoples Temple near where they lived then in Redwood Valley. It had a friendly congregation who did good works. Mary felt it provided answers for her. Soon they were active members. But on what was to become the sisters’ last time together – Mary was on a Temple trip, and managed to get away to visit her family – that H.J. noticed that Mary

seemed angry and strangely detached, and because of that I did not feel comfortable hugging her goodbye…. Instead, I just stood there waving goodbye as they drove away down our gravel road, never suspecting how vulnerable and needy she must have been during that last stolen visit back home.

And I will always, and forever, regret not hugging her one last time.

And Then They Were Gone: Teenagers of Peoples Temple from High School to Jonestown, a book I wrote with Ron Cabral, my fellow teacher at Opportunity High School in San Francisco, has many parallels with this book. The previous passage embodies a deep connection. The loss of nearly 100 of our students in such a horrific event left us with a grief tangled with many other emotions. We too questioned ourselves about what we might have done, and have regrets. Mary and her family left for Guyana on July 17, 1977, the day of the publication of the New West magazine’s exposé of what was going on in the Temple behind closed doors. Most of our students were sent off to Guyana that summer also. We too hoped for letters that never came. Like H.J. Jones, we were to discover much more, and much of it remains hard to read and digest. But in the interest of telling as true a story as possible, Ron and I kept on, as she did. And for us, as well as for her, it was encouraging to find so many good people willing to help us.

Both books focus on idealistic young people who wanted to help create a better, kinder world. H.J. Jones describes her younger sister as “vulnerable.” Our students too, were vulnerable. Like the Wotherspoon family, most of them arrived in Jonestown about the same time that their leader came to stay permanently, creating a jungle prison camp in which people were overworked, underfed, sleep-deprived and often punished, even sadistically tortured, for what Jim Jones, in his increasing paranoia, saw as “crimes.” Both books make readers aware of the cruel fact – still unknown to many – that the babies were killed first on November 18. If there had been any shred of hope left in people before then, it disappeared in that act.

Attempting an escape was the worst offense, the ultimate betrayal to Jim Jones. Tommy Bogue, a teenager in our book, and Peter Wotherspoon were both punished brutally for attempted escapes. Tommy was chained by his bleeding ankle, forced to cut logs in the terrible heat, until Jim’s son and mother – Stephan and Marceline – finally convinced him to release Tommy. Peter was put in the “box,” “a narrow, coffin-like structure … Buried four feet underground, it caused sensory deprivation and claustrophobia for anyone trapped inside, sometimes for days.”

And both books, to borrow Herb Kohl’s words in the Foreword to And Then They Were Gone, search “for hope that seeps through the cracks and insists that love too has a central place in even the most tragic of circumstances.” I often tell people that Chapter 12, “Precious Acts of Treason,” a phrase taken from Deborah Layton’s book, Seductive Poison, is the heart of our book, as it tells of the risks many took in Jonestown for the sake of friendship or love. H.J. Jones learned that survivors had admired Mary greatly for her good heart. She tells of the many acts of generous courage she discovered, both by people in Jonestown and by others who reached out to help during and after the tragedy, many of which I had not known before reading this book.

For example, Congressman Leo Ryan and Richard Dwyer, Deputy Chief of Mission for the American Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana, were to be seated on the first plane out, but decided to surrender their seats to two of the defectors who had left Jonestown with Ryan that day. Ryan himself was killed, and Dwyer, despite being injured himself, worked efficiently to help protect those left on the airstrip after the shootings. H.J. Jones reveals that “out of nowhere, a young Amerindian boy suddenly appeared and then disappeared again after silently leading [the bleeding reporter Tim Reiterman and defector Carol Boyd] into the jungle’s dense, dark safety.” Later, when there were no bandages for Reiterman’s serious wounds, the woman who ran the village pub, Elaine, “offered them some prized new curtains she had been saving,” refusing to accept any payment. A group from the nearby village appeared and after they spoke with the survivors, their elderly leader said, “We are with you. We will help you.” No one knew when another attack might occur.

H.J. Jones also gives credit to the crew at Dover Air Force Base, where the rapidly decaying bodies of those in Jonestown were brought. She says of them, “They were the quiet heroes who bore the stench of death for the rest of us.”

There are many more such stories, but I will end with this one. After a family funeral, at the graveside where all had gathered, H.J. Jones was the last to leave.

I sat on a cold headstone off to the side. Unable to cry before, I now wept as the slow, torturous roll of this still unbelievable catastrophe engulfed me. After a while … I noticed some gravediggers. Two gray-haired gentlemen were leaning on their shovels, quietly looking my way. When they saw me looking at them, they removed their hats, and I was deeply moved by their gesture. It was a simple, but powerful gift of unexpected grace.

(Judy Bebelaar is the co-author of the book, And Then They Were Gone, about some of the Peoples Temple students whom she and the late Ron Cabral taught at Opportunity High in San Francisco in the mid-1970s. Her remembrance of Ron is here. Her collection of articles for this site may be found here. She can be reached at judy@judybebelaar.com.)