(Editor’s note: This article is republished courtesy of MLive.com. The original article appears here.)

(MLive.com editor’s note: This is the final installment of a five-part series on the life of Bay City native Shirlee A. Fields (nee Miller), who was among 918 people who died in a mass murder-suicide in Jonestown and other Guyana locations on Nov. 18, 1978.)

BAY CITY, MI — When Bay City native Shirlee A. Fields died in the jungle-enclosed community of Jonestown on Nov. 18, 1978, her husband and two children joined her.

They were among 918 people who died in the mass murder-suicide led by the Rev. Jim Jones in Guyana. It was the single greatest loss of American lives from a non-natural disaster until Sept. 11, 2001.

Besides the 909 who died at Jonestown and the five killed at Port Kaituma, a Peoples Temple member killed herself and her three children in Georgetown after receiving a radio transmission from Jonestown ordering her to do so, as recounted by Stephan G. Jones in his essay “Death’s Night.”

Several dogs and chimpanzee Mr. Muggs, a community mascot, were also fatally shot at Jonestown, documents and photos show.

Of the dead, 304 were 17 or younger. About 69% of the dead were Black, nearly half being Black women, according to research by Rebecca Moore. Several of the deceased bore puncture wounds from hypodermic needles or abscesses, indicating they did not willingly ingest poison, recalled survivor Tim Carter. Others resisted and repeatedly spat out the poison until they were forced to swallow it, according to survivors Stanley Clayton and Detroit native Odell Rhodes.

Shirlee’s recovered writings don’t reveal if she truly was on board with the mass suicide.

Fielding M. “Mac” McGehee III, a researcher and a leading authority on Jonestown has written that what individuals believed and for how long is an unanswerable question, seeing as how Jones regularly floated the idea of a White Night — his term for crisis drills that often ended in scenarios of mass death

“In the last two or three months of Jonestown, how much did people believe in what they were hearing?” McGehee asked. “The general rank and file, did they believe what Jim Jones was saying? Did Jim Jones believe what he was saying? That really strikes to the heart of how the community functioned.”

Jones’ son, Stephan G. Jones, advises taking Shirlee’s writings with a grain of salt. By the time they were penned, Shirlee and other residents were in a heightened fear state and expected to toe the line, he told MLive.

“They were exhausted, demoralized, and frightened,” he said. “It was hammered into us for years how the outside world was going to destroy us if they got to us or if we went back to the States.”

Shirlee had stated she went to Guyana, at least in part, out of a fear that her Jewish family would face persecution in the U.S. Decades later, this seems sadly prescient, with FBI Director Christopher Wray stating on Oct. 31 that antisemitism in the U.S. is reaching “historic levels,” with 60% of religious-based hate crimes targeting Jewish people.

Scholars have debated whether the Jonestown deaths should be considered a mass suicide or mass murder. For McGehee and his wife Rebecca Moore, who lost two sisters and a nephew in Jonestown, the children and elderly were certainly murder victims.

“For the able-bodied adults and some of the people who were in their late teens, they made decisions,” McGehee said. “They were running a community, and you can’t run a community without people having some independent thought.”

He does not believe everyone was essentially murdered due to brainwashing.

“They had their own agency, they made their own decisions,” McGehee said. “They certainly didn’t join with the idea that they were going to die, or wake up on Nov. 18, look out the window and think, ‘It’s a beautiful day. I think I’ll commit suicide.’”

McGehee and Moore’s website The Jonestown Institute features a section of different positions on the murder-or-suicide angle.

Stephan Jones maintains most of those who died were forced to do so. Even those who drank the poison could not have been in their right minds, given the terror and duress they were subjected to in the preceding months, he said.

“For most of them that night, any allegiance they felt was to the people who had already died or who they believed to be doomed,” he said. “Easily 80 to 90% who stayed were there for the community and not for my father.”

Stephan Jones was in Guyana’s capital of Georgetown when the deaths transpired. Since that day, he’s grappled with how things could have played out differently with his presence in Jonestown. Had he and other dissenters been there, he believes they could have prevented deaths, and would have stopped the pivotal airstrip shooting of U.S. Congressman Leo Ryan’s entourage who came to check on the wellbeing of those in Jonestown.

Stephan Jones said he believes the Fieldses were among those who died out of solidarity with their fellow residents.

“Even though I had turned away from my father, I never saw myself leaving the community,” he said. “That was my entire world. I think that was the case with a lot of people, including the Fieldses. That final night, the people who could be counted on to stand up to my father weren’t there.”

Stephan Jones has written several essays on his time with Peoples Temple and his processing of its tragic end. Understandably, he has conflicting emotions when it comes to his father.

“My father was a lost soul,” he said. “He was a sick man, I feel, from very early on. In his childhood, he learned to play for people’s favor. I think somewhere along the way, he learned to evaluate himself through other people’s perceptions of him. And I have compassion for him in that regard. But, on some days, it’s difficult to view him clear from what he did to my loved ones and what he did to us. There are still days when I gnash my teeth when I think of him.”

Thirty-six people survived in Jonestown. This includes a woman who slept through the deaths, three men who separately escaped the compound, three who were sent by Jones to carry money to the U.S.S.R. embassy in Georgetown, 11 who left on foot that morning, and defectors who joined Ryan’s entourage.

After several delays, the bodies of the dead were flown from Guyana to Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. The 412 who went unclaimed, including Shirlee and Don’s son Mark, were interred in a mass grave at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California.

The bodies of Shirlee and Donald Fields and their daughter Lori are buried at Eden Memorial Park in Mission Hills, Los Angeles, California. They have separate, modest markers bearing their names, the years of their lifespans, and a Star of David.

As subsequent generations continue evaluating the colossal loss of life in Jonestown, Stephan Jones urges they do so with empathy and compassion rather than knee-jerk judgments. He encouraged people to look through the scores of photographs of Peoples Temple members and Jonestown residents.

“Some of the very best people I’ve ever known, many of them, were in the Temple,” he said. “Some of very worst were in it, too. It was a rich community with so many lovely people. Better people than me lost their lives on that last day.”

The deaths can still serve as a warning to others who may find themselves part of a movement that turns controlling, Stephan Jones said. No matter how good something initially appears, one should listen to their gut when they begin sensing something amiss, he said. This is especially true when a movement’s leader presents him or herself as being superior to their flock.

“Good and evil can exist in the same organization and in the same person. No matter how much good they show you, if they show you evil, pay attention,” he said.

Jonestown was abandoned after the deaths. The jungle soon reclaimed the land, making it look as though the town that began in idealism and ended in horror never existed. Yet the ghostly voices of Shirlee Fields and the hundreds of others who died there echo through the timestream, asserting they lived and their stories are worth sharing.

“We have so much to learn from each other, we human beings,” Stephan Jones said.

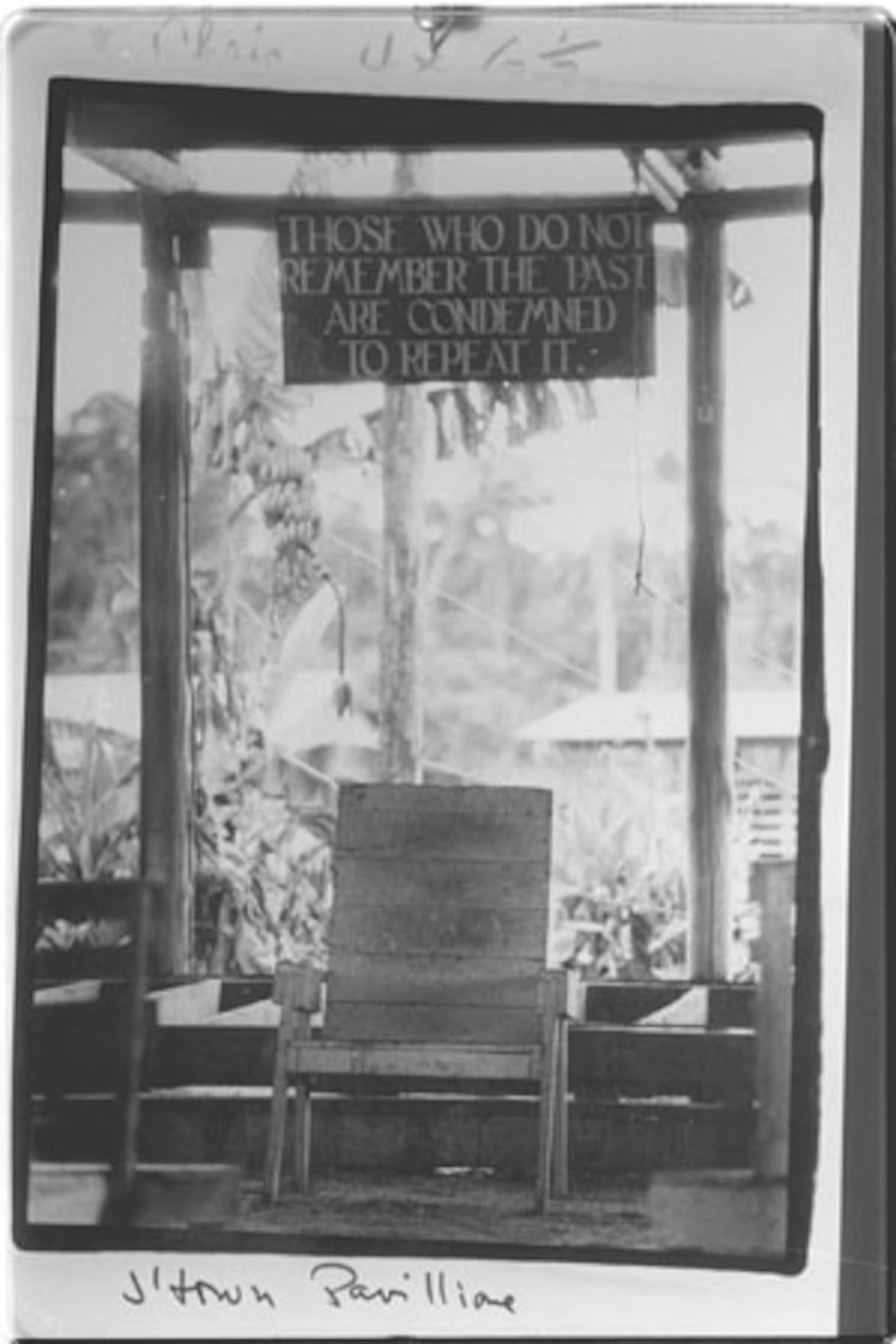

As the banner that hung above Jim Jones’ makeshift throne in the Jonestown pavilion proclaimed, “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

(Cole Waterman is a Michigan-based crime reporter with a long-held interest in Peoples Temple and Jonestown who has submitted numerous primary source transcripts from the FBI’s FOIA files to the site beginning in the fall of 2023. He can be reached at Cole_Waterman@mlive.com.)