(Editor’s note: This article is republished courtesy of MLive.com. The original article appears here.)

Lo! Death has reared himself a throne / In a strange city lying alone / Far down within the dim West, / Where the good and the bad and the worst and the best / Have gone to their eternal rest. ~Edgar Allan Poe

BAY CITY, MI — The 18th of November isn’t significant to most. Yet for those with an eye for history, and an interest in how something can start with the best of intentions before falling to the nadir of human nature, it is marred by a black cloud.

As April 15 is to the Titanic’s sinking or Dec. 7 is to the Pearl Harbor attacks, Nov. 18, 1978, is remembered as the date 918 people died at the direction of the Rev. Jim Jones in the sweltering and nigh-impenetrable Guyanese jungle.

“Don’t drink the Kool-Aid” became pop culture’s callous takeaway, often still uttered by people who aren’t aware of the expression’s macabre origin. Like so much in the public’s perception of Jonestown, the phrase is inaccurate (it was Flavor Aid mixed with cyanide, not Kool-Aid).

I don’t recall what sparked my interest in Jonestown. I simply don’t recall a time when it didn’t fascinate me. Probably I first overheard it referenced in news reports of the Branch Davidians’ 1993 siege in Waco or the Heaven’s Gate mass suicide in 1997.

Something about a movement that began in unabashed idealism and opposed society’s noxious isms then spiraled into madness, murder, and suicide innately intrigued me. The story runs the gamut of humanity’s extremes — hope and altruism corrupted into despair and self-destruction.

Then there is my fascination with Jones himself. Unlike most notorious figures in history, he began his career doing a lot of good, helping the downtrodden and doing his part to end racism and class divides. What could push someone who started so benevolently (at least publicly) to become so warped?

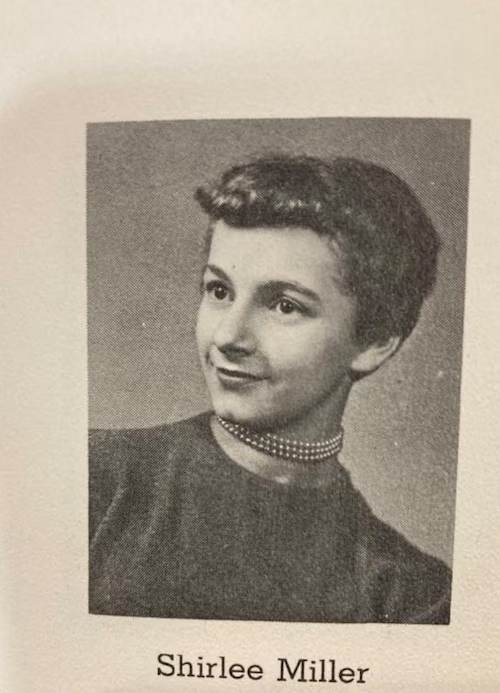

In 2019, I was reading the list of all those who died that day. My jaw dropped on seeing the name Shirlee A. Fields (nee Miller), her hometown listed as Bay City, Michigan.

From her passport photo taken shortly before she left America for Guyana, Shirlee stared eerily across the decades. Her chin raised, she gazes proudly with a slight grin and hopeful eyes, as if she is privy to some great secret.

Learning a local woman died in Jonestown, someone who walked the same streets and saw the same buildings as me, left me staggered. What was I to do with this information? Did other locals know it? Would anyone care to learn it?

I largely sat on this tidbit, occasionally telling friends about it as little more than trivia. Yet as the 45th anniversary of the tragedy neared, the now-or-never element needled me.

I hoped to get an article out of it. I ended up with a five-part series.

Poring over U.S. Census records, Bay City Times archives, and documents retrieved from Jonestown, and speaking with some who remembered Shirlee, I was able to put together a timeline of her life. Daily, I would come home from work champing at the bit to share my discoveries with my girlfriend.

I found myself unable to stop speculating on what was going through Shirlee’s mind as she lived in the isolated compound.

What were Shirlee and her family doing that tense night of Nov. 17, 1978, when U.S. Congressman Leo J. Ryan’s investigative envoy arrived in Jonestown? Was she among the terrified who put on a good public face, or was she a genuine reveler? Was she hoping the delegation would rescue her and her family, or was she eager for the “intruders” to leave their sacred home?

Then there was the chaos of the next day, after Ryan’s delegation was joined by several defectors and left Jonestown, only to be fired upon by Peoples Temple members at a nearby airstrip. As Ryan’s assassination occurred, Jones ordered his flock to ingest cyanide-laced punch, saying their “revolutionary suicide” was necessary to prevent outside forces from taking and torturing their children and seniors.

What was Shirlee thinking as the horror unfurled? Was she cheering in support of her and her family’s looming deaths, still devoted to the cause? Did she believe her family would be killed by military forces and that swallowing poison was preferable? Was she struck numb and frozen? Did she make any attempt to avoid what was coming?

My mind raced when thinking of those residents who resisted and were forced to ingest the fatal mixture or were pricked with syringes.

Were Shirlee or husband Donald J. Fields among those who resisted? Or did they willingly poison their children, Lori and Mark, then themselves? Did Shirlee gaze into the sky and consider the same boiling sun was shining down on her hometown of Bay City, a continent away?

It’s shuddersome to ponder.

When I started this project, I feared it would be met with indifference. Would anyone care about a Bay City woman who died nearly a half-century ago? Does her story, and that of Jonestown in general, still hold value and relevance?

Judging by responses to the series, the answer is unequivocally yes.

“Thank you for this great news find,” reads a comment from one reader on the Memories of Bay City Facebook group. “Went to school with Shirlee and never was made aware or heard Shirlee being part of the Jonestown tragedy.”

“I had no idea someone from Bay City was part of this! Wow,” added another commenter. Another person replied to this comment, saying she had taught a class on cults and also didn’t know of the local connection.

“This was very strong work that hopefully illuminated people who had little to no idea about what really transpired,” added a user of the Jonestown subreddit.

Among those who contacted me after my series began publishing was Tim Chapman, who at age 28 was among the first four photographers to arrive in Jonestown after the tragedy. Working for The Miami Herald, he took the first color images the world would see of the strewn bodies.

“I knew who, what, where on Jonestown but have never figured out why,” said Chapman, now 73 living in retirement in the Florida Keys. “I had to photograph this event to show the world the truth and not follow madmen. It haunts me still.”

Jonestown still garners heavy interest and has cast an indelible mark. Like the Holocaust before and 9/11 after, it is often evoked as a gruesome historical goalpost. Unlike those horrors, though, the Jonestown incident has been met with much more dismissive and dehumanizing gallows humor.

Even now, the incident is frequently namedropped in disparate corners. In the last week alone, I paused twice on encountering unexpected Jonestown references. The first happened on picking up a Stephen King novel I’d not touched since high school and finding King mention Jonestown in its foreword. The second was played for laughs in a “30 Rock” rerun.

Writing the series, I hoped to humanize Shirlee and, by extension, the hundreds of others who died with her. I wanted it to be clear she was a person, one who came from a middle-class family, graduated from college, worked in a cancer clinic, and hoped to make the world better. She lived, married, had children, loved, and feared. Yet her fears and hopes led her to make choices, small at first, that grew and culminated in her being swept up in a force larger than any one person could control.

Contrary to snap judgments, neither she nor anyone else joined the movement thinking it was a “suicide cult.” At the same time, Shirlee’s writings show the mental state she was in as the community slid toward collapse. Her later writings ostensibly see her advocating for mass suicide, yet there is an obvious disjointed feeling in the grammar and syntax. What degree of stress and exhaustion was she under when she wrote those words? Was she forced to pen them?

Was Shirlee Fields a victim or perpetrator? The truth, like so much else surrounding Jonestown, does not lend itself easily to stark black-or-white conclusions. The important thing to me is I documented Shirlee’s life and revealed a complicated individual.

To me, the enduring lesson of Shirlee’s life is how people in search of more can be led to their doom by a misguided leader. And how deeply heartbreaking that is.

Shirlee’s life stands as a caution sign, as huge swathes of people being led astray by megalomaniacal leaders has not abated in the generations since her death.

As Jim Jones’ son Stephan G. Jones told me, “If a leader is presented as being superior to his or her followers, especially if they allow it to happen or do so themselves, I can think of no reason, no movement, no matter how good it is, to stay in that organization. If there is no real way to express dissent or disillusionment or disagreement, no matter how lovely the community might feel to one, I think that is a reason to get out.”

Until we fragile and flawed humans can better heed such warning signs, or until demagogues lose their lust for power, Shirlee and the 917 others who died with her will remain as signal fires in the dark.

Before signing off, I must extend my gratitude to Fielding M. “Mac” McGehee III and Rebecca Moore of The Jonestown Institute and its comprehensive website, Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. As leading authorities on Peoples Temple, the couple was invaluable in my research, making their depths of knowledge accessible no matter how many times I called or emailed them. Always, they were encouraging.

Since 1999, the couple has published the annual Jonestown Report, featuring scholarly articles, research pieces, book reviews, artistic interpretations, survivor testimonials, and biographical profiles on Peoples Temple members.

I also owe Stephan Jones special thanks for taking the time to speak so candidly with me about his memories of the Fields family and his experiences with Peoples Temple. His outlook of empathy was refreshing and humbling. His writings can be found here.

Lastly, a special thank you to Ruth Neitzel and Colleen Turmell, two kind local women who were friends with Shirlee and graciously shared their memories of her.

(Cole Waterman is a Michigan-based crime reporter with a long-held interest in Peoples Temple and Jonestown who has submitted numerous primary source transcripts from the FBI’s FOIA files to the site beginning in the fall of 2023. He can be reached at Cole_Waterman@mlive.com.)