When we became close friends in the mid-sixties, Linda Harris – who was known as Linda Sharon Amos after she joined Peoples Temple – was an attractive, bright, Jewish woman with eclectic interests including social work, Jungian analysis, the I Ching, and reincarnation. She was petite, with long dark wavy hair. Using proceeds from her grandmother’s estate, she had purchased a new Volkswagen Beetle and a two-bedroom bungalow in Albany, California, where she lived with her nine-year-old daughter Liane. She was pursuing a Masters in Social Welfare degree at Cal, as was my husband Chuck. During her second semester of graduate school, our mutual friend Deneal moved in with her and Liane.

Deneal was African-American, with a tidy goatee and short-cropped hair. He had dropped out of law school in the ’50s after an experience he referred to as “enlightenment” in order to practice and teach Zen meditation and Tai Chi. After moving into Linda’s house in 1965, he evicted Liane from her bedroom to create a meditation room. Liane moved into the laundry room, where Deneal constructed a loft for her to sleep on. Although the Bay Area was blooming with flower children in flimsy mini-dresses and sandals, Deneal insisted that Linda and Liane wear below-the-knee skirts, oxford shoes, and bobby socks. Declaring Linda’s new VW too small, he traded it for a used Ford sedan. Linda had been facilitating therapy groups attended by friends and fellow grad students, but Deneal took them over, changing the focus from psychological to spiritual. He then pressured Linda to drop out of graduate school.

Early in the summer of 1966, I announced that I was pregnant with my second child. A week or so later, Deneal told us that he’d had a “visitation” informing him that Linda was also pregnant, and that their son Wayborn would be born on Christmas morning. This was years before ultrasound or amniocentesis, and when I asked Linda if she was really three months along, she said she thought so because her last period was very light. I told them I planned to have my baby at Berkeley’s Herrick Hospital and asked if Linda would do the same. Deneal said they were going to have a home birthing, and asked me to assist.

Chuck and I enrolled in Lamaze childbirth classes, and since Deneal wouldn’t let Linda attend, I taught her the Lamaze breathing exercises. We made baby clothes together and shared the anticipation and discomfort of our pregnancies. However, Christmas came and went without Wayborn’s appearance. So did New Year’s and Valentine’s Day. On February 19, 1967, I delivered my daughter in the hospital after a two-hour labor with manageable pain and no drugs. Linda was still pregnant.

Her contractions finally began early in the morning of March 7th, so I went to their house where I did Lamaze breathing with her, nursed my daughter every few hours, and kept an eye on my five-year-old son and Liane. Linda’s water finally broke mid-afternoon. When her baby’s head crowned, Deneal and I were on each side of the bed. Linda gave a final push, and a plump, dimpled infant emerged into our hands. A girl!

I held the newborn as she took her first breath and turned pink. Deneal cleared her nose, rinsed her eyes, and cut the umbilical cord – techniques he had learned from books. I bathed her in a rubber dish pan while Deneal helped Linda expel the placenta. After I diapered and wrapped the baby in a receiving blanket, Linda took her to her breast. When Chuck arrived, we prepared dinner, and Linda got dressed and joined us at the table where we shared a bottle of brandy. Linda and Deneal named their daughter Wayborn Christa. We never discussed why she wasn’t a boy or why the child had not been born on Christmas.

After Chuck completed his graduate program in June 1967, we moved 120 miles north to Ukiah, where he was hired to counsel alcoholics and drug addicts committed to Mendocino State Hospital. A Berkeley friend had referred us to an unusual church just north of Ukiah that attracted followers intent on creating a more just society, and put us in contact with a church elder who lived in our neighborhood. So when Deneal and Linda (who was pregnant again) were visiting one Sunday in September, we decided to follow our neighbor’s car to the church.

Many African-Americans filled the sanctuary, which was quite unusual in our mostly-white logging and farming community. The pastor was in Canada that week, so a team of elders took turns leading the congregation in prayer, as well as in Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger songs. We also heard the congregation testify to the good works of the pastor, including his ability to read minds and heal the sick.

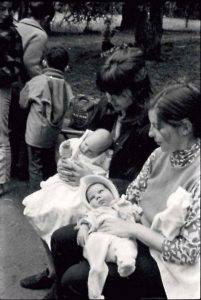

After the service, our neighbor invited us to join the congregation for lunch, where an overweight white woman exclaimed over Christa’s mixed-race beauty and asked Linda if she could hold her. The woman told us that she and her family had followed Jim Jones to Northern California because he’d had a vision that when the nuclear holocaust hits, the Redwood Valley will not get fallout. As she spoke, she looked only at Linda. I felt invisible to her. Rocking Christa in her plump arms, the woman told us that Father knew everything she did, even when she had been eating ice cream, which she said was her weakness. Looking at her heavy body, I didn’t think her oral indulgences were a secret, but Linda appeared mesmerized by her. We were all invited to return the following Sunday to meet her pastor.

Deneal, Linda, and their girls stayed with us the following week. Tuesday afternoon while Chuck was at work, the doorbell rang. It was the elder whose car we had followed to church, and he asked to speak to “Lydia.” I asked if he meant Linda and invited him in. Perched on the edge of a chair, he seemed to be reading from an invisible scroll on my living-room floor. He said that Father had a vision and called him from Canada, telling him to go to our address and tell Linda that he saw her hanging clothes on the line, and that she and her daughter were in danger. He said that Jones described her exactly. He also told us that Jones was flying back from Canada and would be at the county librarian’s house for an antiwar meeting that evening. He invited us to attend.

The chilling forecast left us stunned. After the elder left, we tried to figure out what it meant. What kind of danger? Which daughter? What clothes line? Deneal and Linda didn’t question the authenticity of the vision, but I suggested our visitor hadn’t said anything he didn’t already know after meeting Linda on Sunday. They dismissed my skepticism, and fearing the prophesy, Linda didn’t let Christa and Liane out of her sight. Finally Chuck came home from work, and after a quick dinner, we drove to the librarian’s house with our four kids.

Although the business of planning an antiwar demonstration was completed in an hour, no one left. Apparently we were all waiting for the pastor. My daughter had a cold and was fussy, so I sat on a dining room chair pushed up against a wall, nursing and comforting her. My son and Liane hung around me, looking bored, while Chuck socialized with colleagues from work. Meanwhile Deneal sat in a corner cross-legged, with a very straight back. And with six-month-old Christa on her hip, Linda introduced herself to church and other community members.

Finally Jim Jones arrived, announcing that new converts would be moving from Canada to join Peoples Temple. I watched the handsome, charismatic pastor work the room like a movie star greeting adoring fans. Then I watched Deneal as he watched Linda introduce herself to Jones, trying to lead their conversation to the vision delivered by the church elder. However, Jones didn’t acknowledge that anything unusual had happened and, after inviting us all to church on Sunday, he left.

During the rest of the week, we discussed what the so-called vision meant, and why Jones hadn’t acknowledged it when speaking with Linda at the librarian’s house. Chuck and I suggested that the elder had made it up. But Linda kept both of her daughters within view at all times, and Deneal spent many hours meditating.

On Sunday we sat near the rear of the crowded sanctuary. About 45 minutes into the service Jones asked if anyone needed to be healed. Several people rose and mentioned afflictions. He called them to the front of the sanctuary, where he touched them and exchanged private words. Then Linda stood up, passing Christa to Deneal. “I have a terrible pain here,” she said, clasping her stomach. Jones asked her to step forward, so she walked up to the altar. He then laid his hands on her head and stomach, and whispered to her. She returned to our pew trembling, with a flushed face.

After the service we asked Linda what had happened. She said she couldn’t talk about it.

We decided to stay into the afternoon for lunch. Linda stood near the buffet table, looking up at Jones with adoring eyes. This behavior roused Deneal to fury, and they argued all the way back to our house. Linda finally told us that Jones said her pain was from cancer, and that he had healed her. They continued to argue for several more hours, before they left for the Bay Area.

Chuck and I discussed what had happened and agreed that it was easy to “heal” someone of a nonexistent disease. We also agreed that Linda was vulnerable and unhappy with Deneal. But I thought they’d probably work through their problems because, after all, they had a child together and another on the way. However, a few days later, Deneal reappeared at our house in their Ford – alone – with a suitcase and a few books. He said he’d left because Linda had emotionally left him.

I phoned Linda. She was angry that Deneal had taken the car, and said that she’d be moving into a house in Ukiah that the church had found for her as soon as she put her Albany house on the market. I told her to slow down and give herself time to think about what she was doing, but she said she knew what she had to do. I tried to assure her that Chuck and I weren’t taking sides, that we loved them both and wanted to support her. However, she insisted that she had made up her mind to join the church and would do it without Deneal. When she said Jones had told her to break all ties with her past, I urged her to reconsider her decision and to stay in touch.

A few days later Deneal left for an isolated cabin in Big Sur. I didn’t call Linda again because I wasn’t sure how I felt about her decision. I thought leaving Deneal for the church might be a good choice. They had fought a lot, which wasn’t good for the kids, and church members had reached towards her, apparently sensing her unhappiness. On the other hand, I didn’t buy the faith healing and didn’t like the way the congregation worshipped Jones. Also, I was pretty sure Deneal would be out of Linda’s life completely if she joined the church.

A few weeks later, Chuck learned from a colleague who belonged to the church that Linda had indeed moved to Ukiah. He got her address, and I decided to visit without calling ahead. After bringing my son to kindergarten one morning, I drove with my daughter to Linda’s address and rang the doorbell of a small house near the center of town. Linda answered with a look of surprise, asked how I’d found her, and said she was really busy. She seemed uneasy but finally let me and my daughter in, then turned from me and walked over to the wall furnace to tinker with knobs, mumbling about not being able to get the heat on. I told her that Deneal went to Big Sur for a while, but we expected him back in a week or so. She responded that she didn’t want to see him, and demanded that I not tell him where she lives. She also said she didn’t want to see me or Chuck either, because Father told her to leave her old life behind. Then she asked me to go. I did so, hoping she’d made a good choice.

While shopping at Safeway about six months later, I spotted Linda in the produce section with Christa and an infant in her grocery cart. As I approached, she turned her back, maneuvering the cart between us. I asked her the baby’s name and birthdate – Martin and April 19th, she said with some reluctance – then she pushed her cart towards the checkout line. When I asked how she was doing, she said she did important church work instead of wasting time meditating, and had a job at the welfare department. When I asked who watched the kids when she was at work and if she needed any help, she said the church took care of them. I felt as if I was dragging basic information out of her, and she wouldn’t meet my eyes. By this time she had paid for her groceries, so I followed her out of the store, but was unable to engage her in further conversation. She got into a car with her children and groceries, and drove off. I never saw Linda again.

During the next year, two of my friends and I choreographed a modern dance based on a poem called “The Creation” that we performed at the local Methodist church. It was well received, so we sought additional venues. I thought of Peoples Temple and telephoned Jones, who said he’d be happy to have us perform for his congregation and would get back to me with a date. After one of my dance partners moved away, I called Jones back and left a message that we couldn’t perform at Peoples Temple after all.

But I did hear from Jones. He phoned my house one day when Chuck was at work, saying he needed to tell me something that was very difficult for him. Of course I feared that something had happened to Linda or her kids. Instead, he told me that there were two men in Ukiah who were doing real men’s work. He considered himself one of them, and my husband, who was directing a drug program, the other. He said it was his duty as a responsible pastor and community leader to tell me that Chuck was a drug addict. When I replied that was definitely not true, Jones said he had this information from a reliable source and would help me cope with my problem. I asked who his source was, but he wouldn’t say. I told him I wasn’t interested in hearing unsubstantiated gossip, thanked him for his concern, and hung up, angry that he’d tried to manipulate me. Jones called me again several weeks later, and that time I felt he was coming on to me sexually. I suggested he call back in the evening and talk to Chuck. I never heard from him again.

Early one morning in San Francisco about ten years later, I made my morning coffee, then fetched the Chronicle from the front yard. I unfolded the heavy Sunday paper in my peaceful kitchen, then gasped as I read the lead story: Linda, who was then known in the Temple as Sharon (her middle name), had been found dead in Georgetown, Guyana, along with her three children, their throats slashed. It appeared they had been murdered.

Believing Deneal should get the shocking news from a friend rather than the media, I phoned him in New Hampshire where he was living with his new wife and children at a spiritual commune he had established there. We both wondered what we should do. Then the full extent of the Peoples Temple tragedy unfolded during the next several days, including the likelihood that Sharon had been instrumental in the deaths of her children and herself. When we spoke again, Deneal assured me there was nothing either of us could do. We’d had no contact during the eleven years that she’d been involved in the Temple, and we truly didn’t know what her life had been like. She was no longer the Linda we’d known.

It was not until I read Tim Reiterman’s book Raven about four years later that I learned details of what had happened in Georgetown. According to his account, when Sharon heard Jones’ order for everyone to die, she took a large, sharp, butcher knife from the kitchen and led her three children, along with another Temple member and a young girl, into the bathroom. She told the man she was going to kill her children before the police took them, and ordered him to kill the other girl. He watched without interfering as she slashed the throats of Christa and Martin. Then she gave him the knife, and after he superficially cut the other girl, she took the knife back and gave it to Liane. Guiding the blade with her own hands, she made Liane assist in her mother’s suicide. Liane then slashed her own throat. Although the man did not actually kill Sharon and her children, he was sentenced to prison for his role in their deaths and the attempted murder of the injured girl.

How could my former friend have cut the throats of her children? How could any mother do such a thing? Jones’ other followers drank poison in a large group with him urging them on, but Sharon killed her children and herself many miles away from Jonestown, far removed from whatever pressures drove the people of that isolated jungle community to make their decision to die. Sharon’s final act did not fit my memories of the Linda I knew and loved.

(Ann-Marie Askew can be reached at amaskew1@comcast.net.)