You may remember the story of Ann Elizabeth Moore from 40 years ago: she was the camp nurse of Jonestown, Guyana. Annie was reputed to have supervised the mixing of the poisoned grape drink and to have helped facilitate the November 1978 Peoples Temple massacre. Several months before, she wrote a memo to herself to plan this event, to make sure that all – not just some or most – of her fellow community members would die. There are reports that, once the poisoning was complete, and surrounded by more than 900 bodies as they were beginning to putrefy in the jungle heat, Annie was the one who murdered Jim Jones, the leader of the community, with a bullet to his temple. Then, as the last living person in that remote compound, Annie apparently shot herself in her head. The massacre was an unspeakably evil act and a dark day in history.

You may remember the story of Ann Elizabeth Moore from 40 years ago: she was the camp nurse of Jonestown, Guyana. Annie was reputed to have supervised the mixing of the poisoned grape drink and to have helped facilitate the November 1978 Peoples Temple massacre. Several months before, she wrote a memo to herself to plan this event, to make sure that all – not just some or most – of her fellow community members would die. There are reports that, once the poisoning was complete, and surrounded by more than 900 bodies as they were beginning to putrefy in the jungle heat, Annie was the one who murdered Jim Jones, the leader of the community, with a bullet to his temple. Then, as the last living person in that remote compound, Annie apparently shot herself in her head. The massacre was an unspeakably evil act and a dark day in history.

I knew Annie Moore. I knew her before that event. She was in my life – back when she was another person, when she was a good person. The year 1968 is when my story, my eulogy, of Annie Moore, the nurse of Jonestown, begins. It is not a history or straight narrative. Others have done and will do much better. Instead, this story is personal and therefore biased, editorial and opinionated. It is reflective, and a story more about spirit, not flesh. But it is not intimate.

First Contacts: School and Church

Life in the City of Davis and the Davis United Methodist Church

What Did We Believe? Faith, Social Issues and Unconsciousness

Faith and Activism: Methodism, the Vietnam Conflict, Annie and Me

Knowing Annie: Social Circles and Romance at DHS

Yolo County Foster Children’s Camp

First Contacts: School and Church

This is the first part.

In early July 1968 when my family arrived at 809 Pine Lane in Davis, California, the country was in turmoil. Four months before, Martin Luther King had been assassinated. One month before our arrival in Davis, Robert F. Kennedy had suffered the same fate. The North Vietnamese Tet Offensive was seven months old, and the body count of US soldiers killed in Vietnam was skyrocketing. In the next few months, students on university campuses around the country were bringing education to a halt through non-violent protest. The following month, the Democratic National Convention was brought to its knees while rioting crippled the host city of Chicago. The country was in existential spasms, and many wondered whether anything would ever be like it was before. Some historians call 1968 “the year that shattered history.”

That’s what was going on when I met Annie.

Annie and I first met in that city at Ralph Waldo Emerson Junior High, then located on B Street near the intersection of Russell Boulevard. We were 14-year-old goofy and gangly teenagers. My family had just moved from Huntington Beach in Orange County in southern California to Davis in Yolo County, west of Sacramento in northern California. My father was beginning his career as a practicing pathologist at a laboratory on Anderson Road near the intersection of that same Russell Boulevard. We were waiting for a ranch house to be built a few miles outside the city limits in the West Plainfield District of Yolo County. The house on Pine Lane was within easy walking distance to Annie’s house a few blocks away on Villanova Drive.

I knew Annie from church as well. In all our moves during my childhood years around the western part of the country, my nominally Christian family had settled into identifying tentatively as Methodists. Once unpacked, we began attending the United Methodist Church at the west end of Anderson Road near Covell Boulevard. Phil Walker was the pastor. The congregation was peopled by professional and academic families like us. Nice people. I also recall attending a few Methodist Youth Fellowships meetings in the Moore household during our first few years in Davis. Annie’s father, John, was associated with the congregation as the campus minister at the University of California, Davis. Ken and Diane Wagstaff were among the first families who reached out to my parents, and they became friends for the time of our family’s membership at Davis UMC. I sometimes saw Annie sitting with some of her family members in the pews on those Sundays when we worshipped there. She seemed remote, quiet and a bit stand-offish, so we didn’t talk much.

In those days Annie Moore was a name and face that swirled around my social awareness. She represented a person that I knew of but did not know. I’m sure we spoke, I’m sure we had some classes together, I’m sure we ate lunch at the same table in the cafeteria. I recall seeing her in my classrooms and the hallways. As the year went on, I’m sure she knew most of the people I knew within my social circle of Emerson and through Davis United Methodist Church. I’m sure I thought well of Annie. I’m sure.

School and church. That’s how I recall first meeting Annie. She was okay.

Life in the City of Davis and the Davis United Methodist Church

Davis was unlike any town my family had lived in before. Although relatively small, Davis is a university town, and, like Woodland, the county seat a few miles away, it has always been a critical business-agricultural hub in Yolo County. The university not only offers a world-class education in agriculture, it also boasts world-famous veterinary and medical schools. It is a city surrounded by some of the richest soil on earth and is populated by PhDs in pickup trucks and hybrid cars, involved in cutting-edge agricultural and medical technology living in environmentally efficient housing complete with solar panels… and riding bicycles. Lots and lots of bicycles.

During the spring time, the entire city smells of newly-harvested tomatoes and in the late summer the aroma of newly cut alfalfa; in the late fall the fields are burned, providing for smoky air, spectacular sunsets and reminding us all of Davis’ connection with the land.

The city’s cultural demographics are expressed in a syncretic joining of a class of various types of university academics to a class of well-established landowning class of literate, professional farmers and ranchers. I haven’t been back to Davis in years, but if California could have listed a city that represented the western equivalent of East Coast “town and country” upper-class liberal, Democratic intelligentsia, Davis would have been on the short list. “Limousine Liberalism,” was the title my Republican father derisively gave to the political and social culture of the town where he had brought his family.

Davis seemed to have no poor. It has been the opinion of some that the Davis City Council has tried over the years, unsuccessfully, to exclude poverty out of the city limits through passing various types of zoning and building code legislation, not through providing enough other government services – all this while at the same time holding up a banner of compassion and activism in behalf of the less fortunate and oppressed… in other parts of the world. This is not to say that the poor do not exist in Davis. California in general is overflowing with impoverished households. They’re just relatively invisible and, at least in Davis, limited principally to the university students. Like it or not, along with its dominant liberal politics and worldview, classism has been a self-evident aspect of Davis’ social and political legacy. I’m not convinced that this portrait is fair, but I guess that it must be difficult to be a Methodist or socialist in a social and political environment such as this. Suffering is probably more often witnessed by a Davisite by using a TV remote and attending notable visiting speaker UCD campus events. To see real poverty, a Davisite needs to travel. I wonder whether this apparent duplicity annoyed – perhaps infuriated – Annie.

Reflecting the Kingdom of God in the transformation of society, as I have learned in later years, has been one of the most important hallmarks of the Methodist tradition. Like the tradition’s founder, John Wesley, whose firebrand preaching was accompanied by the championing some of the important social causes of his day – like the injustice of black slavery in the colonies and the oppression of the poor by the wealthy – I heard appeals for justice, compassion and equality as a constant theme throughout my family membership sojourn at Davis United Methodist Church. If there is any way that a Methodist might measure the depth of commitment to God, a commitment to these causes would be it. This commitment is woven integrally into America’s religious history and is part of many liberal Americans’ personal spiritual identities. And the more I got to know Annie in the coming years, the more I learned that these were the issues that put a fire in her belly and animated her spirit. In spite of how funny and easy-going Annie was, these matters were serious, and she had a conscience.

None of Annie’s father’s sermons or Phil Walker’s sermons moved me. One would think they would have. The Vietnam conflict was dragging on. President Lyndon Johnson had sent in a massive increase in troops. I figured that at that rate, I might be up for the draft and shipped off to the Mekong River Delta in the coming few years. And even if the war had ended before my eighteenth birthday – or even if I had never been called up – the ethical question concerning the US involvement in the war had been the focus of every evening news report and many classroom discussions at school. One would think the sermons at the United Methodist Church would mean something immediate and pressing to my heart and mind. But they didn’t. Not to me. I wonder what they meant to Annie. I don’t recall her ever quoting sermons from that pulpit, or any pulpit for that matter. In fact, I don’t recall her talking to me about anything in the Bible. Not to me.

What Did We Believe? Faith, Social Issues and Unconsciousness

As I approached my eighteenth birthday and as the Vietnam conflict continued, I had to make some of my first life-changing ethical decisions regarding my relationship to that conflict. Should I break the law and not register for the draft? Should I burn my draft card if I got one? Should I dodge the draft? Should I register as a Conscientious Objector? Should I flee the country and renounce my citizenship? As a minister of the Christian faith, the Reverend John Moore’s counsel in this regard to these questions would prove critical to me.

I recall those few times alone with Rev. Moore in a spare room on the Davis High School campus, in those private conversations we had about the Vietnam conflict, about war in general, about the prospect of being drafted and about possibly dying in the rice paddies or jungles of that enigmatic land. I recall Rev. Moore asking me many questions about how I felt about the war, about war in general, about the draft and about related issues.

But I have no recollection of Rev. Moore, a university campus pastor and one charged with the care of souls, ever asking me about my faith. He did not ask about the nature of my relationship to God or even what passages of Scripture that I was using to form my understanding of the conflict. I have no recollection of him trying to help me connect my faith to my ethical principles or moral actions. He never asked, “Buck, what do you believe?” Not about the war, but about deeper matters as well. Perhaps he felt that, since we were on a high school campus, it would have been a violation of the church-state relationship. I don’t know. I wish he had been civilly disobedient instead. This is because, in those days, I had no faith to articulate. I wasn’t aware of my own faith; evidently neither was Rev. Moore aware of my faith. Because of this, I was unable to draw my own conclusions about the basis of war and of civil disobedience and protest. I needed an epistemological and ethical foundation. I didn’t know what I believed. I was conscious of the Vietnam conflict, but I lacked a consciousness of God. The world was a mess, my mind lacked fundamental tools to resolve my dilemmas, and my heart was cold and silent.

Somebody else asked me the question instead. When we were at Emerson Junior High, I had an embarrassing schoolboy crush on a girl named Nancy Morris. That crush lasted well into my first year at Davis Senior High. One way that I tried to impress Nancy was by behaving “philosophically.” I wasn’t a musician like her, so I had to find some sort of “in.” I needed “game.” My clumsy method was to appear wise, pensive and philosophical. I had read Will and Ariel Durant’s cheap and readable paperback, The Story of Philosophy, which in my adolescent mind qualified me. Never mind Kant, Marx, Fichte, Heidegger or Wittgenstein. Plato and Aristotle as secondary sources were enough.

So, one day, there we were: sitting on Nancy Morris’ front lawn on Sycamore Lane, the two of us watching the clouds go by and me searching for important things to say in order to impress her. After a short pause in our conversation, Nancy took me down with a single question, “What do you believe?”

I was unprepared. This was a question I was supposed to ask others. In a flash, I searched my mind and came up with a stock set of faux confessional statements about some divine being who existed in some sort of spiritual form and that it pervades all things both transcendent and immanent. God existed in the flowers, the grass and in me and in her. It was, in short, a lame and cobbled together bunch of pedantic scraps that I had gathered from TV shows, cursory readings of popular literature (like Jonathan Livingston Seagull, On the Road by Jack Kerouac, The Prophet by Khalil Gibran and Autobiography of a Yogi) and coffee table books. I pasted these concepts into something resembling an incoherent, paper-thin version of New Age clap-trap.

The answer did not get me a date, but there was a positive effect of Nancy’s question. I was put on alert to do some serious thinking and even some soul-searching. Fortunately, Nancy did not pursue my confession and embarrass me further. But it was Nancy Morris, not John Moore, who got me thinking – hard.

I tell this story because I wonder why Annie never asked me this question. My conclusion is that, like her father, in the four years we nurtured our friendship, I don’t think it ever occurred to her. Perhaps it was too intrusive for someone who didn’t know me that well. It wasn’t her responsibility anyway. Of course, neither was it Nancy’s.

Faith and Activism: Methodism, the Vietnam Conflict, Annie and Me

I did not come from an activist family like Annie’s. I was from a family of parents who practiced medicine and saw the world from pragmatic, culturally-conservative, Republican eyes. Justice was important to them in principle, but not worthy of urgent, radical or revolutionary social disobedience: as the son of a semi-nomadic medical student for thirteen years, I was born into modest means, but my family and I weren’t caught in a hopeless cycle of poverty. We knew that the constant moving –that the baloney sandwich lunches and the macaroni-and-cheese dinners – would end one day. After we moved to Davis and my father passed his pathology board exams, he was launched into the social status of an official medical professional, and our family was inaugurated into a life of middle-class security. But even in my family’s “salad days,” we never felt the pain of empty stomachs, the threat of eviction or the fear of violence from those more powerful than us. Perhaps that’s why my extended family’s investment in maintaining the status quo was greater than others’. The sacrifice we practiced was reserved for family, for those in our lives and for the community; it was bounded by financial and time limitations and by the moral obligations of the Hippocratic Oath. The afflictions of the world in general seemed to be, practically speaking, the concern of others, of those who had their own side of the street to keep clean.

To that extent, I was a family outlier, but not because I was willing to sacrifice (at least in principle) for justice and equity. Rather, I was driven to find out the “what” that underlies ethical principles, as much as the “why” of moral outrage. What is the basis of justice, equity and compassion? The matter of belief was more on my mind than the matter of action. But some issues were, regardless of belief, to me and Annie as well as many of my generation, cause for action. By the time Annie and I turned sixteen years old, one of those issues was the Vietnam conflict.

For Annie, the immorality of US involvement in the Vietnam conflict was self-evident. And it wasn’t just the war. For Annie, the whole world was filled with injustices, inequalities, brokenness and oppression. As we moved from Emerson Junior High to Davis Senior High, where Annie and I would spend some of the most important years of our young lives, I recall standing next to her and others in the rain on the DHS campus on “Vietnam Moratorium Day” as we read the names of those hundreds who had been killed or were missing in action in Vietnam. Where Annie’s spirituality was expressed in actions such as these, my participation was motivated by something less clear to my mind and heart. The war – and many other situations that made the world less than a paradise – was wrong. But I couldn’t say why. I needed more. Annie didn’t. While I spent perhaps too much of my time and effort thinking and talking about these issues, Annie acted.

Knowing Annie: Social Circles and Romance at DHS

By the time we began attending Davis Senior High in September of 1969, I knew who Annie was, and we spent time together. She and I ran in an ethnically and religiously diverse circle of students. We were among the sons and daughters of UC Davis professors and the professional class of society representing that certain slice of the city’s substantial bourgeois upper middle-class. It was difficult to differentiate between those who were part of this group and who weren’t (back then they were called “cliques”), but we were constituted of about fifteen to twenty or so who found a certain affinity for each other’s company. The boundary between those inside or outside this circle was fluid. We went to some but not all the sports rallies and games, and few if any of us used illegal substances or indulged in under-age drinking. In spite of the 1967 Summer of Love in San Francisco’s Haight-Asbury district and the sexual revolution of the entire previous decade, we did not indulge in indiscriminate, lascivious sexual activity.

Most of us were “the good kids” who expected to go to the more reputable universities, who took advanced level classes taught by the UCD graduate students and not the regular high school faculty, who dated and formed romantic relationships amongst ourselves and who ran for and often won positions in the student counsel. Annie was one of us, and it would have been unthinkable to see her as a person capable of killing her fellow human. Annie was good.

Although shorter than I, Annie had a lanky frame like mine, often bore a contemplative and mysteriously self-satisfied smile. She walked with a certain gait that betrayed a certain goofy and care-free pensiveness, like the beat of a slow blues rhythm. She rarely seemed unhappy. She played the guitar, and with her long, dark blonde hair, she even looked like a folk singer. She joked more than most, but said less. She enjoyed learning not just to play folk and blues music but also understanding the world views of folk musicians like Peter Seeger and Woody Guthrie. She introduced me to the important blues roots musicians like Leadbelly, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Blind Willie Johnson, and Sonny Rollins and Brownie McGhee. Eventually I learned to love the music that she had not only known for years but whom she intuitively understood since childhood. It was in part her influence that got me to pick up the guitar for a few years. What moved her inwardly concerning issues of justice were outwardly expressed in how she listened to and played music. She breathed it, and I picked up on the sound of her spiritual movements. To this day, when I hear this kind of music – even some Bob Dylan – I think of her.

In contemplating my 40-year-old high-school memories of my relation to Annie, most are a chronological jumble. But there were certain events involving the two of us in that DHS social circle. One was awkwardly romantic. Many of the more eligible among us dated each other, and predictably I myself took a glance at Annie. I bounced the idea off the minds of a couple of my friends, who shrugged their shoulders and counseled me to “go for it if you wish.” – not a rousing cheer of approval. Nevertheless, I approached Annie and she impulsively brushed me off. After that incident, I noticed that Annie seemed to form her closer relationships with her female friends. Except for perhaps Ken Risling, the boys never got as close. Not a single relationship Annie had seemed to possess the character of a romantic or sexual desire. Others may disagree, but she seemed a bit allergic to true intimacy in any package, and from my own limited perspective, the intimacy of dating and romance just didn’t seem to be her cup of tea at all.

But there may have been more to it. I don’t think any guy could have gotten past her “bullshit detector,” an almost innate sensibility Annie had in determining the sincerity of a person’s motives or commitments. And my motives were, albeit sincere, lacking in sincere commitment. I suppose that no one could have won Annie’s heart unless that person embodied the ideals and virtues Annie treasured as holy and sacred. If, as some of her letters suggest, Jim Jones had become Annie’s most treasured confidant, the emotional sway he held over her would have made sense, and it must have been powerful.

Yolo County Foster Children’s Camp

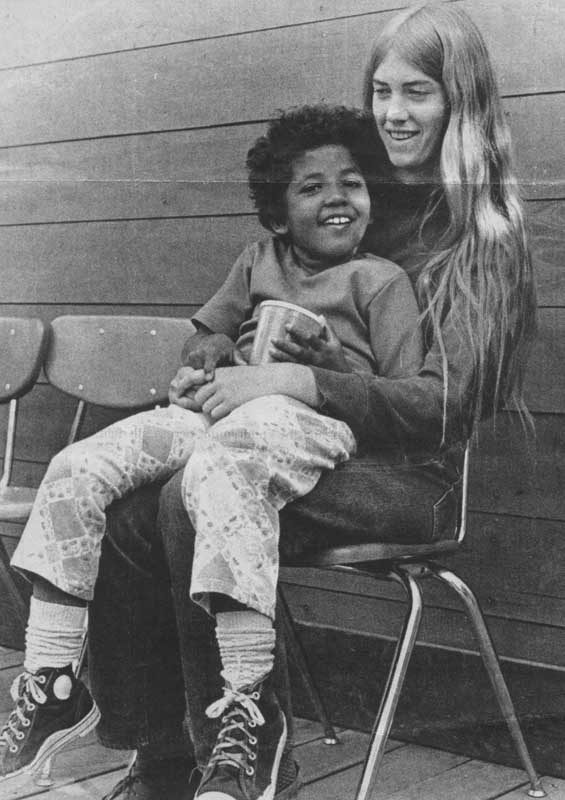

Annie and I had another connection outside Davis Senior High School and outside of worship services at Davis United Methodist Church. During our high school years, we were involved in a summer camp for foster children who lived under the care of Yolo County Foster Care Services. Most of the counselors were supplied by high school students associated in some way with DUMC, which sponsored the camp.

Every summer Annie and I, along with about ten to fifteen other teen counselors, would spend a few weeks in a forested compound in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. (For two of those years Ken Risling was also among the counselors.) The organization assigned each counselor one (and only one) foster child of our respective gender, each between the ages of seven and twelve. Each one of us counselors were to befriend, mentor and guide our one child. We ate with them at the table, worked with them at crafts, played with them in sports activities and slept in the same communal tent with them at night.

The logistics of this one-on-one, counselor-camper pairing made sense after only a few hours with the kids. Given the tumultuous and traumatic character of children in foster care – most of whom are treated as irrelevant extras in the dramatic scenarios of what is presented to them as “family life” – consistency and exclusive attention is of the most important gifts we could have given them. For children like this, having the assurance that the person taking care of you today is the same one who had the task yesterday and will be the one who will be there tomorrow – is a tangible and reliable aspect of love that many of them had never had. It was only a few weeks for them, but those two weeks were a nice reprieve for most of them.

And Annie was good at giving this kind of tender care. Even as a teenager, she could behave like a mother. She would stroke the hair of her charge or sit the child in her lap as effortlessly as anyone with maternal instincts would. For me, my foster child’s need represented a pleasant and rewarding type of work; for Annie it was effortless pleasure. No wonder she became a nurse.

The Jesus Movement and Our Spiritual Lives

Besides school, church and the youth camp, Annie and I had one last common connection – or rather lack thereof. And this is the one that is most important to this part of my story. It had to do with our spiritual lives.

In the years that Annie and I were acquainted, a certain spiritual movement was afoot and especially active in California. This social-spiritual phenomenon came to be called “The Jesus Movement.” History records that the Jesus Movement started in California and spread throughout the United States on the heels of the already-burgeoning worldwide Charismatic Movement, a brand of neo-Pentecostalism that broke all sorts of social, ethnic, class, denominational and national boundaries. To some, except in certain manifestations and except in their historical timing and duration, the Jesus Movement and Charismatic Movement were often experientially, practically, socially and dogmatically indistinguishable. To others, the Charismatic Movement remains alive even today in many developing and underdeveloped countries, especially in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia. By contrast, the Jesus Movement faded by the mid-1970s, but it also morphed into its own type of “denomination” known as Calvary Chapel (now worldwide) and spawned a commercial music enterprise called the “Maranatha Music Ministry,” now a division of Universal Music corporation.

My personal familiarity with the Jesus Movement began with my introduction to the ministry of a young man named Chuck Smith and his work initially among a group of surfers in the Newport Beach, California area. In contrast to the almost universal appeal of the Charismatic Movement that affected those both inside and outside church walls, the Jesus Movement seemed to attract principally those young counter-cultural misfits who saw themselves as societal and ecclesiastical dropouts, those who had rejected the forms and practices of organized religion, especially the Christian religion. When Smith, a former hippie, surfer and pot-head himself, encountered these young people on the beaches where he himself used to surf and live, he engaged in a personal, face-to-face form of relationship evangelism. Even though they smoked marijuana, ingested various hallucinogenic and psychogenic drugs, and engaged in sexual activity outside marriage and a host of other activities that one might consider “non-Christian,” Smith considered these people from whom he emerged as the most eligible to hear and respond to the Gospel message of Christ’s sacrifice and resurrection.

And they heard and responded. And I did too. The Jesus Movement made itself known to me and others on the campus of Davis Senior High School through certain other students who had been powerfully transformed by listening to and responding to a message I had never heard before: that the divine and human Jesus Christ gave himself to atone for the sins of many, including mine.

After sitting in the pews of Davis United Methodist Church and many other pews in many other cities in which my family lived, one would suppose that I would have heard this message. I hadn’t. I had been baptized as an infant on February 14, 1954, but I was never informed what baptism meant except that my parents told me that I “belonged to Jesus” – whoever he was. I was ignorant of almost every aspect of the core of Biblical truths. In fact, I have no recollection of having read a Bible on my own until I turned fifteen years old. My parents bought me a Revised Standard Version of the Bible in my early teen years, but I hadn’t read it. I didn’t know how to. I didn’t know the difference between the Old and New Testaments, and I didn’t understand the meanings of the term “chapter and verse.” No one had taught me, and it didn’t occur to me to ask. Even while my family was attending a church and I heard passages of the Bible read from the pulpit, I didn’t get it.

Until early adolescence, what I understood about the Christian faith from the culture and from my upbringing was that Christians are good people who do good things. They lived in places like Oak Park, Illinois and Davis, California – places where I’m from. Being a white middle-class American seemed to be the functional equivalent of being a Christian. Those of Hispanic background were “Catholic” and, for reasons that never made sense to me, were under the authority of some guy in Rome called “the Pope.” Jews were not Christian but must be respected for the suffering they experienced in World War II. Most Christians were white and from European ethnic background. Many others were black but didn’t go to the same churches I go to. As the years passed, each of these simplistic icons have been smashed. Larger realities abounded, and my own primal search for truth stripped these false images away as much as Annie’s own primal desires pressed her onward to realize an earthly utopia of universal justice and racial equality.

I was also taught by the culture that, just like those in other religious faiths, we all believe in the same deity. For Annie, this surface equivalence did not seem to be an issue; for me, it was. All these impressions of the various faiths were, of course, somewhere between facile images I had obtained from the media and others that seem outright false. I had a lot of work to do.

To Annie, even before she met Jim Jones, the human race seemed to be destined for a glorious unity; to me, I saw unresolvable disunity and confusion. Since Jews and Muslims didn’t believe in a trinitarian god, since Hindus were polytheistic, since Native Americans were animistic, etc., no one – not Joseph Campbell, not Huston Smith, not Alan Watts, not Noam Chomsky, nor anyone else – seemed to clear up this discrepancy to my satisfaction. I had spent almost all my life in multicultural, multi-ethnic and multi-faith environments, but the painting never made much sense to me, nor was it useful. I began to feel that what members of these varying faiths believed was sincere and internally consistent. I also believed that saying that we all believe in the same god was an exercise in herding cats, forest sprites and angry bulls, then in stuffing them all into a flimsy intellectual gunny sack – a container that held none of them effectively and just made them angry with each other and with the holder of the gunny sack.

I have come to the conclusion that, regardless of certain formal correspondences and the primal human desire for deep affiliation for the divine, most people on earth indeed believe differently, and they worship and serve different deities. Academics can speak of ideas and symbols that resolve to some transcendent unity, but the typical human relates to the deity with his or her own heart. And the heart rules the mind. We can still hold hands and sing “Kumbaya” all we want, but the blood still flows, and, as Stephen Prothero in his book, God is Not One, the paths really are different, and the violence finds its origin in belief. This is not Karen Armstrong’s view, but it has become mine.

My own understanding of the Christian faith in those days in Davis and earlier was informed more by the sentimental reflections of the guests on the Lawrence Welk Show and the platitudes I heard on Bonanza and Leave It to Beaver episodes. I absorbed more from Disney and Cecil B. DeMille movies than from church. It was sentimentality over substance. For me, the center could no longer hold. For Annie, this dilemma was apparently not an issue. At this level of perception, she seemed free of any static or dissonance.

My problem up until around 1968 was that I was a Christian in name only, and I had no apprehension of the meaning of the Gospel message. Religion was a social phenomenon in which I played a bit part. Even though I had heard the words, I didn’t know the meaning of terms like “holiness,” “sin,” “righteousness,” or “atonement.” No one had explained them to me because I didn’t ask. Worst of all, I didn’t know who Jesus really was – or should I say, “is.” I was swimming in an ocean of ignorance and misinformation derived from watching the popular version of Christianity that was filtered through television, advertising and children’s stories about how to behave well. In essence, I hadn’t been taught Christian faith; I had been taught about something I later called a whitewashed version of post-Kantian pharisaical moralism delivered to me via network TV.

Whereas Annie seemed to be spiritually alive in her advocacy for causes like Civil Rights Movement and an end to US involvement in the Vietnam War, I was spiritually dead, and I didn’t know it. The spirit who animated her was apparently of only passing interest to me at the time. Annie was on a deliberate path; although restless and searching, I was still wandering aimlessly in the woods.

It wasn’t until late in 1969, while I sat in the living room of a family who had opened their home to an organized youth ministry called Young Life where I heard (or at least understood) the Gospel for the first time. Young Life is a world-wide evangelical student organization that began in Texas in 1941 and that ministers to high-school aged teens. In the days of the Jesus Movement, Young Life welcomed many of the manifestations and work of the Charismatic Movement in general. The Gospel story I heard in that living room that night from the Young Life leader was from Luke 19 about Jesus’ meal in the home of a despicable Jewish tax collector named Zacchaeus, who profited financially by extorting his own people in behalf of the hated Roman occupiers. I was completely gripped.

What I heard was not a story about how Jesus modelled a way for me to become a good person or to manifest God’s love through his example – the story I had understood heretofore from pulpits of the congregations that my family and I had attended. In that living room I heard instead the story of a horrible man who God (in the person of His Son, Jesus) took the initiative to love. Since I ran with “the good kids” at school, the message about my own sinful condition and need for redemption didn’t completely penetrate my heart at first, but the shock and revelation were immediate: God loves the unlovable, and he demonstrated it through the sacrifice of his Son on the Cross. Like the rich young man of Mark 10, I didn’t need to be good; I needed to understand another vision for myself and to walk a different path altogether.

Eventually, over the next several months and by early 1970, I got the idea: everyone on earth, including me, is trapped in a world of sin, pain and brokenness, and everyone on earth, including me, needs the atoning sacrifice of Jesus’ sacrifice on the Cross to be in an acceptable relationship with the living, holy God of creation. Although the evil in this world is real, that very well-intentioned evil was defeated by means of the most evilly heinous act ever undertaken: Deicide, the murder of God. Eventually, I collapsed into the arms of mercy, surrendering my own goodness to the arms of a forgiving God. I’ve been doing the same thing over and over thousands of times since then. It’s been a humiliating joy.

By the end of my time at Davis Senior High in 1972, I had gone from “a good kid” to one of the “Jesus freaks.” In the parlance of evangelicalism, I was “saved.” The transformation did not alienate me from most of my social circle, and even Annie did not shun me for the changes in my outlook and attitude. In the meantime, my family had long since stopped attending Davis United Methodist Church… or, for me, any church at all, for that matter, and especially the Methodist Youth Fellowship. For a while my attitude was that organized church bodies were, at the very least, dead. At worst, they had stopped preaching the Gospel and were misleading people directly into hell. Yes, that’s a horribly judgmental and prejudiced attitude. Since then I’ve become much more nuanced and reserved in my judgement. I still judge unfairly at times, though. But that’s a different story.

What effect did the Jesus Movement have on Annie? I don’t know. We never spoke to each other about these things. That’s information. What I knew in myself is that I had gotten a passion for knowing God, for learning the Bible. From that encounter I was moved to advocate for many issues, including, like Wesley, social justice. I had begun a lifelong and often rocky and uncertain journey in moving from the wellspring of mercy and justice to expressing these same attributes of God’s character in the world.

As I’ve noted many times, Annie had a passion for justice. This passion had become, in the words of Ephesians 2:10, her “good works” for which she was created. And when we walked across the platform to receive our high school diplomas and then parted ways by the end of the summer, this was my assessment of her: a clear-eyed young woman with a spiritual passion for justice, for racial and economic equality, for a world in which all humanity could live together in harmony. At the time, back in the spring of 1972, I felt that Annie was more firmly spiritually rooted than I was. I assumed she understood the meaning of the Cross. After all, she was the daughter of a minister. I assumed that she would go far and do well. Really well. Better than I could hope for myself. It was only after many years, while I reflected upon the foundations of her life, and especially the circumstances of her death, that I asked myself, “where was Annie’s spiritual wellspring?” What nourished her spiritual life?

That’s the second part of my story.

After graduation, Annie and I never saw each other again. Almost all of us scattered to the winds of various colleges and universities. I don’t know really what happened to her heart or mind. Unlike Ken Risling, Eileen Allen, Meryl Rappaport, Jeanne Jasper, Roxanne Goddard and many others among our circle who were more important to her personally and emotionally, Annie and I did not keep in touch through letters or visits.

I was unaware when she had moved away from Davis and that later she had begun studying to become a nurse. I did not know that she joined Peoples Temple late in that summer of 1972. I didn’t even know the name “Peoples Temple” or the name of its pastor, Jim Jones. I was even unaware that Annie’s sister Carolyn (whom I never met) had formed a romantic and sexual relationship with Jones in 1968 or that Annie had a nephew as a result of that affair. Considering all that I’ve learned about Peoples Temple and Jonestown, whatever happened to Annie must have been gradual, outside of the awareness of those around her, even while she was in high school. It may not have been that alarming either, since in those days radical socialist ideas have always been common among academics. We had lived through the “year that shattered history” already. Besides, the US has always been a cradle for utopian spiritual communities like New Harmony and Oneida among scores of others. I suppose no ideas seemed too radical by then.

Her letters after 1972 indicate that Annie had indeed been forming radically different beliefs than I about what it meant to be a Christian, possibly even while I knew her. For instance, it appears that her idea of the Kingdom of God became coterminous with a socialist utopian community on earth in the here and now, and that this idea could be achieved… with or without God’s Holy Spirit. Mine was, and still is, that this reality, like cyanide in pure water, continues to be laced with real evil, and that the community of believers here on earth, in time and space, reflects an imperfect, not-fully-formed version of heaven itself, a place in which Christ, and no other human, rules absolutely. We live after the inauguration of the Kingdom already… but not yet. Until the Last Day, we continue to “see through a glass darkly” (I Cor. 13). We groan inwardly for a glory to be revealed.

More ominously, Annie seems to have conflated the messianic character of the founder of the Christian faith with a man named Jim Jones. In 1973, Jones announced, “for some unexplained reasons, I happen to be selected to be God.” In whatever manner one frames this statement, unless intentionally comical and sarcastic, the meaning is more than alarming. And I do not believe Jones was being comical or sarcastic. These were the days in which Jones had also introduced the concept of “revolutionary suicide,” a term I’ve seen in certain primary documents.

Through scores of sources, most anyone can now find plenty of detailed information on the personality, character, preaching, teaching and actions of Jim Jones. Jones came from Indiana to California in a quest to find more fertile soil for a spiritual movement that manifested outwardly the Biblical (and, more importantly, socialist) principles of racial equality and economic equity for the poor. From those years in Indiana and up until his departure to the agricultural project in Guyana, Jones himself continued to undergo a gradual transformation. The ordained Disciples of Christ pastor of Indiana, a man married to a faithful wife and mother to many in the church community, this man began moving his attention from the God whose saving love he was commissioned in his ordination vows to proclaim, in the words of the Apostle Paul in his letter to the Galatians, “another gospel.” I wonder if he ever preached Paul’s Gospel. I have found no evidence that he did and plenty that he did not. Unlike Annie, Jones seems to have been bent and wounded from birth. Unlike other bent and wounded souls, he never seemed to have been restored or brought to spiritual health.

Many sources assert that Jones’ focus was never truly on the Biblical Gospel but upon the building of some form of socialist utopia that had at least a vague, surface correspondence to a Christian community devoid of any foundation in the person of Christ as Lord. This was not unique: Lenin (among many other revolutionaries) used Christian Scripture out of context to legitimate his own agenda, and Jones had studied, among many others, Lenin. None of my sources indicate that Jones even wished to understand the Biblical principle of Christ’s lordship. Being the ordained pastor of a Christian congregation was simply a useful cover. My knowledge of the history of various denominations in the US suggests to me that the less doctrinally focused Disciples of Christ is one in which a type of “cult of personality” leadership was easier to implement and allow to thrive without careful oversight. It still permits great latitude in political viewpoints, governs itself on the congregational level, and espouses a very basic (albeit admittedly solid in many respects) doctrinal statement. I never learned how the denomination responded to the Peoples Temple movement before November 1978. The dynamic oratorical skills that Jones had in spades may have obscured any of his political, doctrinal or moral idiosyncrasies. His skillful manipulations and lies succeeded in pulling the wool over many ecclesiastical, legal and governmental eyes. For those he couldn’t fool or manipulate, he subdued.

It was in his California years from the late 1960s to around 1974 when Jones’ ministry influence and membership numbers expanded exponentially – and when he himself seemed to go off the rails. He abandoned fidelity to his wife and became sexually involved with others in the congregation. He fathered a child through his first mistress, Annie’s sister, Carolyn Moore Layton. Most dramatically, what I saw in the documentary footage and made-for-television movies was a man who early on shifted his understanding of authority and leadership from the person of Christ and the Word of God (if it had ever been there) to an authority that was based on and in the person of Jim Jones and the words that came from the mouth of Jim Jones. Even back in 1965, he is reputed to have declared the Bible false and himself God’s true prophet. It was in the process of Jones’ more outward transition that Annie left Davis and moved to Redwood Valley to join what I have come to believe was transitioning from the vague and tattered form of a marginally Christian congregation into a full-blown cult-like community.

By the end of the summer of 1972, I had moved 100 miles north, from my family’s ranch house in the West Plainfield District a few miles from the city of Davis, to Chico where I attended a California State University. My major areas of study were Psychology and Religious Studies; I minored in Honors English and History. Most of my free time was spent in my commitment to an international Christian campus organization called Inter-varsity Christian Fellowship. Annie (who by that time was working as a nursing assistant and taking nursing classes at Santa Rosa Junior College) was not on my mind. By the end of that summer Annie became officially affiliated with Peoples Temple. But this was also the time when Jones’ mental condition and drug addiction was beginning to spin further out of control and when the Peoples Temple community itself began circling the drain. The next year, 1973, Jones began to promote the idea of “revolutionary suicide.”

In 1977, one year after graduating from university, having not secured anything near satisfying career employment, and feeling bitter and angry, I pulled up roots in northern California and left the country to live and study in Europe at a religious community known as L’Abri (French for “the Shelter) in Switzerland and France. I studied under the tutelage and leadership of a not particularly charismatic missionary pastor, writer, social critic, theologian and philosopher named Francis Schaeffer and under the care and guidance of many others who worked with him. The residents opened their homes to us and helped me understand more fully the reality and effects of Christ’s sacrifice. “If Christ is risen and the Holy Spirit active today, in space and time and in history, then how should we then live?” It was at L’Abri in which many of my youthful passions were bridled and tamed, and where I learned to live in a broken and imperfect community in which love, forgiveness and mercy were among its more obvious characteristics. Schaeffer, as well as his family members and his associates there, taught me by example to focus my attention on Christ and the Kingdom of God as a method of dealing with the ugliness and brokenness of this fallen world – this because this world is filled with pain and evil, and it wasn’t going to go away on human effort. We lived in community and shared not just our possessions, but more importantly our hearts and lives. People, especially students but also political dissidents, refugees and lost souls from all over the world, rich and poor, from any ethnic background or belief, found food, healing and hospitality in that “shelter.” Many, particularly those not of the Christian faith, were welcomed.

In the meantime, in the same year, Annie and most of the “faithful” in Peoples Temple, many feeling bitter and angry, pulled up roots in northern California and left the country to live in what they hoped would be peaceful community, an agricultural project outpost in Guyana called Jonestown, under the charismatic leadership of a man who had by that time become a drug-addicted, paranoid megalomaniac. Jones’ personal nurse, Annie Moore, did not see Jones in this manner. He wasn’t just the leader. He was their messiah. Annie was evidently Jones’ principal supplier of the medications to which he had become addicted. It was there history records that the utopian socialist community had been transformed, in the opinion of many (but not Annie), into an armed camp. Jones spent most of his time speaking over a PA system, exhorting his followers to focus their attention on him and upon the utopian ideals that the community was built – a Kingdom of God on earth, to have a world of racial equality, of care for the poor, of a socialist utopia. Here, now…and without God. And unclean outsiders were not necessarily always welcomed.

By then time I returned from Europe, Annie and the others had already completed their move to the jungle; meanwhile, I had moved to Sebastopol, California, where I was busy learning New Testament Greek. The residents of Jonestown were preparing the ground for new crops; I was preparing to attend graduate school to study theology. The Jonestown residents were living off the land; in order to pay for a modest room and board, I worked as a cashier at a gas station near downtown Sebastopol. Annie was living and working in heaven; I was living in a borrowed attic and working for a corporate polluter.

That is when and where I heard about the massacre. I had just finished pumping gas when my co-worker emerged from the cash booth. The radio was reporting news of what had happened. She waved me into the room and turned up the volume as we both stood in silence. We must have looked like those who stood by their radios listening to the unfolding events of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, or like those in front of their television screens watching what happened in New York and Washington DC on September 11, 2001. Without even knowing of Annie’s presence there, I froze in silent unbelief that so many had died under the preaching of one man’s deadly, sociopathic influence.

It wasn’t until a few days later that a former Davis High School classmate informed me that Annie had died there. Even more days passed before I learned of her involvement in the mixing of the sedative- and cyanide-laced fruit drink. It took months for me to gather bits and pieces of information. Not just the name Jim Jones, but also Larry Layton, Carolyn Moore Layton and Annie Moore (at times Maria Katsaris) were all names that I heard over and over from various reports over the days, weeks, months and even years since the tragedy. Some of the facts I didn’t learn until later; some information was not factual at all. It was in the ensuing months that I asked myself a question not dissimilar to the question Nancy Morris had asked me in 1970: what did Annie believe? What had led her to this place? To this action?

Almost 40 years have passed since the day I was informed of the Jonestown Massacre, of all the fallout of Annie’s death and of her involvement in that event. I have had time both to meditate and to evaluate the character of my relationship with Annie, what she believed and who she was. Some memories may have become altered to help me make some rational sense of the irrational, the insane and the evil. I’m suspect that I have ignored, edited and redacted. Other memories have faded into oblivion, only to be resurrected by a conversation at a high school reunion or by an offhand comment or anecdote told by another one of our old gang. I have not read many of the scores of books, articles, media interviews, documentaries and films that have been generated since the event. To that extent, I remain relatively naïve to some relevant facts and to the detailed timeline of events.

But time’s river has continued to flow. In 1985 I was living north of Boston in Salem while my then-wife was attending seminary on the North Shore of Massachusetts. I was wandering around the stacks of that school’s library when I tripped randomly upon The Jonestown Letters, a book of letters and journal entries written by Annie Moore and edited by her sister Rebecca Moore. The wound reopened as I paged through the book and traveled with Annie mentally through her journey from Davis to Santa Rosa and Redwood Valley to San Francisco to the Jonestown agricultural outpost. Some of her words seemed familiar and danced in the rhythm of the thoughts and mannerisms that were familiar to my memory of Annie; others did not, especially those letters written later on, especially those that were dated closer to 1977 and into 1978. A website is maintained by San Diego State University has an index that seems to have collected an even greater assemblage of Annie’s personal papers and is probably a more helpful source of information. I notice that in that archive there is not a single item of her correspondence is from her to me or vice versa. This is understandable and indicative of the fact that she and I were not as close as she was to others in our high school group, those whose names I can easily recall as the same classmates we both knew.

All this is to say that I did not really know Annie Moore. Not really. I never spent a single moment of real, true, genuine intimacy with her. We spoke with each other, yes. We shared life experiences and had friends in common. We cared about many of the same things. If you had asked me about Annie and what I knew of her, I’d have responded with a laundry list of her endearing qualities and told stories about her. I would have given her good reviews and smiled as I remembered.

But I have no recollection of experiencing a single moment with Annie in which she turned to me, looked me straight in the eye and said something like, “This is who I am, Buck. This is what I want. This is what I believe.” Nor do I recall saying anything like that back to her. I have no recollection of a moment in which she said to me in unashamed and candid honesty, “Here I am, Buck. Broken, healed, desperate, joyful, beautiful and ugly.” Nor do I recall saying anything similar back to her. I have no memory of mutual delight in our relationship with each other or a transcendent moment in which we knew something of each other’s souls. She didn’t trust me enough. I hadn’t earned her trust, and I didn’t deserve it. I don’t recall a moment of Christian fellowship. But I’m older now and my memory may have edited out such a moment. I doubt it.

To that extent, while I can say that I knew Annie Moore, she was not my friend. Not my close friend. Not the friend I might have wanted her to be. I got the impression that this is not what she wanted from me anyway. I think, and I hope, that she drew from another well to fill that need, that need that everyone has: to be known and treasured. I have learned from the community she was part of, the community known as Peoples Temple – it appears to me that this is the well from which she drew her need for intimacy and for identity. If there is anything that makes me weep about the loss of Annie Moore, this is it. Was she really known? Was she really loved? Did she ever pray to the same God I did? My answer to all these questions is a less-than-fully-assured, “yes” and an unspoken “no.” I will always wonder.

As I was preparing to write this story, I did more research. I read more of Annie’s letters, memos and journal entries, some of which are held by the Jonestown Institute. The tone and character of only some of the letters surprised me. They were mostly filled with the concerns I’d always knew she had and the humorous and somewhat coarse language that was characteristic of her joking and off-hand communication style.

In an early release of one particular made-for-TV film that reenacted the last days of Jonestown, I learned that Larry Layton was not in the camp when the massacre unfolded. And Layton was not, as I had previously understood, the one who pulled the trigger of the gun that killed Jim Jones himself. Rather, Layton was one of those at the Port Kaituma airstrip who participated in the attack upon the congressional entourage as it was attempting to leave; he shot and wounded two people on a small plane before being disarmed. So, the question remained for me: who killed Jones?

It could have been Annie. Although the autopsy on Jim Jones could come to no conclusion as to whether his death was caused by murder or suicide – and although there is other speculation on any of a number of people besides Annie who might have shot Jones – the film Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre strongly alleged that it was Annie who shot Jones and then shot herself. And even if she didn’t commit that crime, there is little doubt that she either participated or assisted in the murders of the children of Jonestown. Annie Moore, the good girl I knew in high school, helped murder children, and then she killed herself.

Here’s what I believe may have happened to Annie Moore. A young woman, passionate to see justice done and racial and economic equality practiced in this world, was seduced. She was seduced by a man who instinctively knew how to satisfy Annie’s deepest desire to see these very virtues fully manifested in this everyday reality. Here. Now. They were able to sneak past the flaming-sworded seraphim, back into the Garden. Back to Paradise. I believe that when Annie stepped into the community of Peoples Temple, and especially into the Jonestown jungle compound, she was able to see, to touch and to experience it, to be satisfied with what she desired the most. She had arrived at a well of justice and equity, and her soul drank deeply from that well. And it satisfied her. Deeply. It became what she was willing to sacrifice everything to retain.

After I learned about the story, the upbringing, the character, the thinking and the deeds of Jim Jones, it was not difficult to hate what he did, even to hate him. As for Annie, even after contemplating her participation in such horrific deeds, I cannot hate her. Other people knew her better, and they loved her. I never got close enough to love her like others may have, but I believe that if she allowed it, I believe I would have. Annie’s was not a death to celebrate; Jones’ was.

In the sacred darkness of predawn hours, I still think of Annie at times. I toss and turn. I want to think, I want to believe that Annie had someone in her life who knew her intimately and loved her truly. (I believe that at least her family did.) I do not want to believe that Annie Moore prepared deadly poison for children to drink. For her sake and for the sake of all who loved her, I do not want to believe that Annie died alone in the jungle in Guyana, surrounded by hundreds of dead bodies, overcome by bitterness, anger, despair and isolation. I do not want to believe that Annie wrote the memo in which she self-consciously detailed the plans to implement the suicides/murders of all the residents of Jonestown. The most horrifying thing I do not want to believe is that Annie Moore is the one who (in an act of deicide?) put a bullet into the skull of Jim Jones, and/or that she was one of the nurses who betrayed her Hippocratic Oath by murdering the children she had previously tended. I cannot conjure the picture in my mind. Nevertheless, these events did happen. She did do those evil things. Surely, she had to be profoundly changed in her heart and soul in order to commit such acts. I do now know why. Nevertheless, I’ve asked myself over the years, “What did Annie come to believe?” For as we believe, so are our hearts; and as are our hearts, so go our lives.

After 40 years since this dark event, I believe it would be arrogant beyond the boundaries of even Jim Jones’ megalomania to presume to explain the “whys” and “hows” of what happened to Annie’s heart and soul or to the soul of anyone who chose to follow such a demented person. Evil as it resides in the human heart has its own ways, and those ways are far more mysterious, deep and cunning than human hearts themselves. King Solomon observed that the intentions of the heart are like a deep well, but a man of understanding can draw them out (Proverbs 20:5). I am not that kind of man. Another of Solomon’s proverbs admonishes, “Guard your heart with all vigilance, for from it flow the springs of life” (4:23). Others have much more knowledge, insight and wisdom, and even they cannot draw firm conclusions. I have written about Annie from only my own limited understanding. And my understanding is limited.

But one thing is clear to me. In these intervening 40 years, I’ve lived in several cultures and in different circumstances, both in poverty and comfort. I’ve been surrounded most of my life among those of different faith communities, languages, nations and economic circumstances. I’ve witnessed horrifying murders and unspeakably moving acts of sacrificial kindness. We believe many things, and, I’ve come to believe, like Dylan’s song goes, that we all serve (or worship) somebody. Annie’s behavior made it clear that she served Jim Jones, or at least his vision, not Jesus Christ.

We humans are worshipping creatures. We are hard-wired to yearn and groan for that which our souls desire the most: communion with the divine and with each other. While we live in the existential here and now, in the present darkness we call out to eternity. We are all deeply restless to see things put right, both in our souls and in the community around us. As St. Augustine’s prayer reflected in his Confessions, “We are made for Thee and for Thy glory, and our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee.” Like me, Annie was restless, very restless.

For those who do not know how to make that divine contact, who have neither the inclination nor the ability to live in the transcendent power of the love of an eternal God, then we worship, we serve (the same word in Greek) other gods – the gods we know, the gods of this world. It appears obvious that Annie fought for and lost a struggle to achieve a socialist utopia in this world, not the next. The next world was irrelevant.

For those who do not serve the gods of this world, some of us are more willing to make our own sacrifice than to accept the sacrifice put forward by (in the understanding of the Christian view) God himself. To them, the Cross is either not enough, not relevant or not real. To atone, to reconcile, to heal, we are willing to sacrifice of ourselves instead – and to sacrifice all of ourselves. To augment or replace God’s cosmically revolutionary action to us, we become willing to engage in our own human form of revolutionary action. Some do. History is filled with this kind of human revolutionary action. People die, often in large numbers. Witness Jonestown…as well as the work of Mao, Stalin and Hitler.

Still others of us, projecting human characteristics onto some other type of remote, angry, transcendent god, are willing to do as the mothers of the Canaanites did: give our beloved children (or whatever is most precious to us) to the flames of the angry Moloch, to turn aside his wrath and assure peace between our god and the community in the world we know. We sacrifice everything precious to us to preserve what we have; never mind achieving utopia or a transcendent bliss. John and Barbara Moore served up their own daughters – unwillingly. That god was not remote, albeit angry.

In part because of Jonestown and what happened to Annie, I now believe that it is critically important to know the names and natures of the gods we worship. For these gods are the ones who will surely require of us not just our heartfelt service, but our very lives. This is what gods are like. This is what gods do. The life and death of my high school classmate Annie Moore has been a case in point. For what she believed, she gave the final measure of her humanity. Even her very life. In her dying breath, she raised a defiant middle finger and then collapsed, unforgiving, into the unmerciful arms of a bitter death, announcing that she “will not rest in Thee.” Not in Thee. In her understanding, she died, they all died, because, we hypocrites, in her final words (and perhaps her epitaph?) “would not let us live in peace.”

So (as a paraphrase and anastrophe of T. S. Eliot’s, “The Hollow Men”) this is the way her world ended, with a whimper and a bang. Kyrie eleison.

Nevertheless, instead of and in spite of the god she served to the end, may the eternal God who is able to do far more abundantly than all that any one of us could possibly ask or think, may that God who is has demonstrated his mercy to all, have mercy, even and especially upon the soul of the daughter of John and Barbara Moore, upon the sister of Rebecca Moore, upon the soul of Ann Elizabeth Moore.

(Buck Butler can be reached at bbbutler3@gmail.com.)