(Editor’s note: In addition to this article, Dominique Z. Delphine has provided a transcribed copy of a taped interview given in 1980 to Tim Reiterman which goes into great detail about daily life and her experiences while in Peoples Temple.)

“We shall not cease from exploration and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we began and to know the place for the first time.” TS Eliot – Little Giddings

My name is Dominique Z. Delphine now. While I was a member of Peoples Temple, I was known as Joyce Cable Shaw-Houston.

For six years and two months, I participated as a member of Peoples Temple Christian Church, Disciples of Christ, pastored by the Rev. James W. (Jim) Jones. I went to my first meeting on May 16, 1970, and escaped on July 16, 1976.

I encountered the group for the first time at the Way Auditorium, which was later purchased by the church and became the San Francisco headquarters. I officially joined the church on January 1, 1971 and moved to Redwood Valley, California in August 1971, where I worked for the Mendocino County Welfare Department as an Eligibility Worker until October 1972. I worked full-time for the church at Valley Publishing from October 1972 until December 1973, when I returned to San Francisco and lived with Janet and David Shular, until I got a job as a secretary and moved into a studio apartment on Fillmore at Haight Street. I married a Temple member, Bob Houston, on October 2, 1974, and we formed the Children’s Commune on Portero Hill in December 1974. I became a member of the Temple Planning Commission (P.C.) on Easter 1975, where I got to see the “real” Jim Jones in action.

This was a real shocker and opened my eyes in ways that lead me to leaving or “defecting” (as Jones called it when someone quit the Temple) on July 16, 1976. I fled to my parents in Ohio. That September I started graduate school at Wright State University majoring in Special Education and Counseling. Bob was killed on October 5, 1976 while working at the Southern Pacific Railroad Yard. I traveled to San Francisco for his funeral and returned to Ohio to finish my college course work.

In July 1977, I moved back to San Francisco where I got a job in a law firm and interacted with Temple “defectors.” On July 24, 1978, I moved to Los Angeles to live with Maria Papapetros and play a larger role in the Human Freedom Center (HFC). I was part of its founding in Berkeley, along with Tim Stoen, Al and Jeannie Mills – who were later murdered – Jim Cobb, Terry Cobb, Maria Papapetros and Joan Culpeper. Joan had been a member of the Heaven’s Gate cult in the early ’70s, and was part of the HFC as an advisor on cults. (Twenty years later in 1997, thirty-nine Heaven’s Gate members committed mass suicide.) The HFC was dedicated to helping former members of all cults reintegrate into society. We worked hard preparing ourselves to help Temple members when they returned from Jonestown which we believed would be in the very near future.

My personal story can be somewhat extended to one of a particular group attracted to Peoples Temple. There were old-time church ladies and gentlemen from Indiana, there were poor people, blue-collar workers, business and sales people, families who needed help with children, addictions, or social service systems. My demographic group was college-educated young people in the helping professions: teachers, lawyers, social workers, doctors and nurses. I can speak only for myself, but my story may be similar to others in this group who were responding to the changes in our society and the spirit of hope and optimism that so inspired us to want to work for a society in which all had their basic needs met and could attain their full potential. My hope is to be a living witness for those whose voices were silenced in Jonestown.

My extended story follows.

* * * * *

Before Peoples Temple

I was born on January 1, 1942, three weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, and grew up in New Carlisle, Ohio, a small farming community of about 1,500 people just north of Dayton. I am the eldest of three children in a working-class family who attended the Methodist church. My father, Aaron Cable, was a handsome, and intelligent man, steady, dependable, sociable, and hard-working with a great sense of humor who was well-liked in the community. Our family’s best-kept secret was his rage and our fear.

Dad was adopted at age eight by a childless, religious, older couple who treated him well, but he came from a traumatic background. His birth mother ran a boarding house for 24 coal miners in a “holler” in West Virginia and had already had three daughters when Aaron was born. He lived with the shame of being illegitimate and not knowing who his father was, which was a horrible stigma in those days. He never publicly displayed the smoldering rage that lived in him, but our family walked on eggshells trying not to provoke his fiery outbursts. We children were regularly spanked with a belt.

Worse than any outburst was the ever-present tension in our home, a constant feeling of being disapproved of, no matter what we said or did. My father engaged in what he called “constructive criticism,” but I don’t remember him praising me for anything. Certainly, there was never an actual conversation between us. Years later, I realized that his rage was projected onto us children, and his own unaddressed woundedness left him with no control over his actions.

My mother, Doris – whom Dad idealized and treated lovingly – took tranquilizers for her “nerves,” as she played the role of dutiful wife while her husband’s rage dominated our home. She had been taught to defer to her husband. Later she expressed regret for not having stood up to him. When he started his abusive behavior toward their two grandchildren, she told him to knock it off or she wouldn’t have the grandkids in their home. Dad instantly changed his ways – or perhaps the fact that grandchildren go home at night helped him maintain control.

Although money was not plentiful, our needs were met, and everyone in town was in a similar financial situation. Having one pair of new shoes and a couple of new outfits each fall was the norm. My parents drove me and my friends around to the various after-school activities and social functions. I was a member of the marching band in high school, attended all football games, and cheered for our basketball team with great gusto.

I had two best friends, Nancy and Anita. We were part of a group of about ten girls called the New Carlisle Gang and were noted for being good students. We ruled second in the social hierarchy while another group of girls called the Donnelsville Gang, from one town over, reigned as cheerleaders and homecoming queens. I was perfectly comfortable in my social niche, dating nice boys and attending prom, racking up good grades and being a member of the National Honor Society.

At the Senior Honors Banquet, I received nine out of thirteen awards. When her friend told my mother how many awards I received, she expressed chagrin that I hadn’t invited them. This surprised me, because it hadn’t occurred to me my parents would be interested. I don’t remember feeling upset about their general disinterest. I was working on a personal goal of accumulating as many lines as possible beneath my senior picture in our year book. I established this goal to pass the time until I could graduate and leave home. I managed eleven lines, as did two other students. However, no one surpassed me!

I knew my parents could not afford to send me to college, but somewhere I got the idea that my way out of New Carlisle was a college education so I could get a good job and my own apartment. I began earning money when I was 10: riding my bicycle around selling Christmas cards, babysitting, mowing lawns and working part-time at a dry cleaners my last three years of high school. Between graduation and the start of college, I worked three separate jobs. My college fund grew to the sizable sum of $1,500.

I counted the days until graduation. While other students expressed sadness at leaving school, I couldn’t wait to go to college, and begin my “real life.” At the time I didn’t think I had a bad home life. From the outside, my childhood looked classically all-American. When asked by a counselor years later to sum up my childhood in one word, the word that sprang from my lips was “terrified.”

I also discovered through counseling that I had suffered from a low-grade chronic depression from a young age. After my father’s death in 1990, I found his birth mother’s family. His mother had died in Dayton State Mental Hospital with a diagnosis of manic-depressive disorder, now called bipolar disorder. Dad’s rage and a dysfunctional household surely contributed to the depression I carried. I appeared friendly and poised, but inwardly I felt like an imposter who never let anyone know the real me. Perhaps I feared telling the family secret of my father’s rage.

The manner in which adults in New Carlisle lived their lives seemed preposterous to me. My parents went to work, came home and worked evenings and weekends at chores connected with raising a family. It didn’t look to me like they were having a lot of fun. Their Midwestern philosophy based on “God, the flag and motherhood” didn’t impress me either. They clearly lived shallow and meaningless lives. With the clarity of youth, I decided I definitely didn’t want a life like that!

In retrospect, I realize my parents enjoyed playing cards on weekends with three couples who had children our age with whom we played. They took vacations, belonged to various social organizations, and had many friends. After I became an adult, I grew to believe that they were comparatively happy.

* * * * *

To quote from a book of that era, the feeling inside me was that: I’m okay, but you are not okay. My sense of being okay was a pose of youthful defiance and a protective defensiveness. I felt disapproved of by my father, so I decided there was something wrong with him. However, because of the way human nature develops in the young, my defiance wasn’t enough to prevent me from believing at a deep subconscious level that there was something wrong with me.

At the time I entered puberty, my hair became thin, which gave me an excuse to opt-out of competing socially for the kind, handsome, professional man I hoped to marry someday. This was a rationalization based on shaky self-esteem. I had a beautiful face and a proportioned figure. However, in my own mind, my thin hair was an insurmountable strike against me.

How does one put words to the pain that gnaws at one’s insides every waking moment and makes it difficult to feel comfortable inside my own skin? Little did I know this is the very essence of teenagers’ dilemmas.

A recent television ad announces, “Depression hurts.” Yes, it does. The “voice of depression” tells you that you are not good enough. It reinforces a sense of being alone and misunderstood, although I never remember feeling lonely or longing for understanding from others — at least not on a conscious level. I was so shut down emotionally that I didn’t feel much of anything. I lived a life colored gray. I could see the beauty of the world, but it didn’t move me. All my energy was devoted to staving off the black hole inside and the fear that if I lost my grip, it would tear me to pieces. I kept going by force of will. Busy, busy, busy. Too busy to look inside.

Not surprisingly, I found booze by the time I was sixteen. I lived with parents who had one drink of whiskey every year on New Year’s Eve. Our town was “dry,” and there were no bars in it. No one I knew drank, and yet I managed to slip into a club with a false ID between my junior and senior years of high school. Some alcoholics say that they were hooked from the first drink because they felt “normal” for the first time ever. I don’t remember feeling that, but I certainly found myself laughing and enjoying myself more than usual. When I had a couple of drinks in me, I was able to interact with boys who otherwise terrified me. “Fortunately”, I am a binge drinker, so I never drank on a daily basis. I did, however, experience blackouts almost from the beginning, and engaged in behavior that did not match my sober moral code.

As a senior in high school – and looking for other points of view, because I found the Midwestern, all-American life I was indoctrinated in to be most unsatisfying – I read The Russian Revolution, by Leon Trotsky. (Was it depression or the rebellion of youth?) I lived in a one-dimensional world, and although I hadn’t known any other, I knew there was something more out there, and I was determined to find it. I had complete faith that with a college degree, I could create the life I dreamed of, although I had no idea what that life looked like! Ah, sweet youth!

I rushed off to Miami University in Oxford, Ohio in September 1959 but dropped out at the end of my sophomore year. I ran out of money and had mediocre grades from spending too much time in the student union hanging out with cute fraternity guys or drinking 3.2 beer at the College Inn with a group of older, male students who called themselves socialists.

I moved back to my parents’ house and got a job but was soon transferred to Dayton where I shared an apartment with two young women. I met a young psychologist with whom I was completely enamored, but a few months later he was killed in an auto accident. I was devastated – traumatized even – but coped by keeping busy and hitting the bar scene.

In 1962, I met Ian Shaw, a refugee from the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. My knight-in-shining-armor had arrived!! He was tall and handsome with an intriguing accent, and was neither Midwestern nor all-American. He worked for a large corporation as an electrical engineer, was worldly, spoke four languages, and had ideas that expanded my own thoughts. I soon moved in with him at a time when it was scandalous for nice girls to move in with a boyfriend. By early 1963, he expressed increasing disillusionment with American culture – as did I, due to his influence – so we both worked two jobs, saved our money and sailed away on a cruise ship ending up in Vienna where we got married on December 12, 1964. After living there for six months, we returned on the Queen Elizabeth I with a new and improved view of the U.S. I worked and went to night school, earning my B.A. in psychology with honors in 1968. Like many young people of that time, I become the first person in my family to have a college degree.

Dayton was now too provincial, so we set our sights on San Francisco where Ian found a job. Soon after we arrived, I landed one at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center, Adult Psychiatry Clinic as a Psychometrist administering psychological tests. We had arrived!! Life was perfect!! Was there a catch?

As it turned out, there was. After six years together, Ian admitted to me for the first time that he did not want children. Up until then, he had said we should wait until we were stable. He now said his nerves were too bad to handle raising a child. I knew his history of living with his wealthy family in Budapest, which was heavily bombed during World War II. At one point there were frozen dead German soldiers stacked in the foyer of their apartment building awaiting burial when the ground thawed. They were in their apartment when a bomb hit and collapsed half the building. Their living room wall was demolished, exposing a seven-story drop. I found out after our separation that Ian was half-Jewish and that his father had escaped from a Russian prison camp. He lived inside a wall in their apartment for two years, which would have meant instant death for the entire family if he had been discovered by the Nazis.

Neither I nor the rest of the world had a concept of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) at that time, but much later I realized he suffered from PTSD. His perception of being poor father material rang true. At the time I was irate, and accused him of having lied to me. He had hoped that I would give up the idea of having children if I got my degree and became a career woman. He figured wrong. I was 28 years old, and my biological clock was ticking, damn it! It was a deal-breaker, and I asked for a divorce which was final in July 1970. Ironically, I never have had children, although I have taken on the mothering role for many young ones throughout my life.

I got my own apartment and continued working at UC-SF, where I became immersed in Jungian psychology astrology, tarot and the Kabbalah. I dated a number of professional men, including an African-American and a Chinese-American, but none were potential husband or father material.

Again – or still – life was good on the outside, but the inner angst bubbled away. My solution came with the grand idea of more involvement in the counterculture. Underneath my professional woman image lived a hippie who did drugs on the weekends because I was too insecure to quit my job and hit the road in my VW camper looking for my tribe. Bottom line: I wanted to join a commune, find a new partner and get high!

Laurie Efrein, a woman I had met in an astrology class called me, on May 16, 1970 and invited me to hear a speaker by the name of Jim Jones, whom she described as a “good man.” I had no information about Jones beyond this, but I attended, and the rest is my history as a member of Peoples Temple.

Peoples Temple Member

At the time of my participation, I was caught up in the rush of being part of a “Noble Cause.” Heady stuff. No time to ponder petty considerations. We were going to transform the world!! I had no idea of what Peoples Temple life would look like, but I had tons of enthusiasm and inspiration.

Recently, I have wondered if the LSD drug trips I took in San Francisco prior to joining Peoples Temple may have made me vulnerable to Jones’ message of creating an ideal society, although it’s also true that part fell in line with my moral code and hope for humanity. But maybe I lost some analytical ability when he said Peoples Temple would lead U.S. society after the nuclear war – which he predicted we would survive in a cave only he knew about. It sounds psychotic now, but at the time it seemed reasonable!

Temple members in Redwood Valley/Ukiah were expected to show up for all-day Sunday services plus Wednesday evening services. When Peoples Temple expanded to San Francisco and later added Los Angeles, we were required to attend services all weekend long. One weekend the service was in San Francisco and on the next one, we loaded up on buses and traveled six to seven hours to Los Angeles for the services. These requirements alone kept us busy. But we also had Temple business to attend to: publishing, housing, food, and medical care. This was a socialist group, and we operated as one: working at jobs to bring money in, and then working to take care of our members.

The trips to Los Angeles coincided with the time period I worked in publications, and later when I managed children and the commune on Potrero Hill and worked full-time. I was beyond tired. On the bus trips to LA, I’d roll myself up in a sleeping bag that was my prized possession, haul myself into an upper luggage rack and spend the six hour trips to and from LA literally asleep in the rack. It was often the bulk of sleep I got for the entire week.

Inner Guidance

I had earlier studied about psychic energy when I lived in San Francisco in the late 60’s, but had no personal experience of it. I was working for the Temple at Sound Publishing in early 1973, sleeping under my desk in my tiny office, when something – a voice? – said, “Wake up!” I immediately jumped up and sat at my desk as Helen Swinney, the Head of Communes, flung the door open in order to talk to me. She was a formidable woman, and even though I was justified in being asleep at 9:00 a.m. because I had worked all night, I was glad I was not caught sleeping on the job, so-to-speak. That was my first experience of this type of phenomenon.

There were other small occurrences after that. I remember a couple of occasions when I would be on a sidewalk in downtown San Francisco, and got the impression that I should cross the street. That’s when I would see someone I was glad to avoid.

One incident stands out. Jim used to hand out small squares of red material he called Prayer Cloths. He allegedly received revelations about people, such as they were about to have an accident or get sick. He would give that person a Prayer Cloth with instructions to wear it on their person for protection. I had a number of them pinned to my bra. I was working late at a law firm in about 1974 and when I went to the restroom, I got the impression that I was supposed to flush these cloths down the toilet. At first, I was dumbfounded. Such a thought had never entered my mind. I hadn’t put much emphasis on the healings. I was open to Jones’ healings, and was glad if anyone was cured or protected, but didn’t feel any sort of reliance on his gifts for myself. I was there for the socialism first and foremost. However, I wore the clothes for good measure. It didn’t hurt, and it might help. When I received this inner instruction, then, I did hesitate briefly before flushing them. I believe this type of item does carry an energy charge and may exert some small force in connecting the possessor to the person from whom it was received. This is speculation. However, this action did represent my tangible first step in unhooking my energy from Jim Jones.

So many years have passed that I cannot recall other specific incidents. However, these are some of the ones that caught my attention, and started me being aware of some type of Inner Guidance and to trust in it.

Leaving Peoples Temple

Ultimately, my Inner Guidance lead me to my departure from the Temple. I was in excruciatingly painful, confusing conflict at the time I was contemplating leaving. It is some of the worst torment I have ever felt.

I had written a letter to Jones in September 1975 with 14 questions mainly about organization and administration. This led to a five-hour ordeal of me standing on the stage at a Planning Commission meeting being questioned about my dedication to the Cause. A few months later, in March 1976, the order came down saying we would all eat every meal together every day at the Peoples Temple building. The Potrero Hill Commune had to move to Sutter Street to be close enough to follow these instructions. But, the children in our commune were not getting enough to eat so I tried – and failed – to get permission to have a tub of peanut butter and some bread for the children when they came home from school. This is the same period when we had an all-day event in Redwood Valley, and Irvin Perkins, who worked full-time on Temple buses, asked for something more in his sandwiches than beans, saying he could not work twelve-hour days on a bean sandwich!

How could a socialist organization ignore our pleas for more food?

Before I left the Temple, I wrestled with enormous conflict around Jones’ policy of opening the doors to all comers. We struggled to integrate new members into our “family.” Many newcomers were drug addicts who needed detoxing, and others suffered from traumatic backgrounds and were bottomless pits of legitimate needs. Opportunists looking for a free ride joined up, too. Most Temple Members worked full-time jobs and dealt with other church demands and family responsibilities. The quantity of work we did resulted in us getting only three or four hours a night of sleep, a regime that lasted for years.

We know now that sleep deprivation is used as a torture device and that long-term deprivation is even more of a torture. I came to believe it was a strategy of Jones’ to keep us too busy and tired to think. I was beyond exhausted, and I became resentful. By the time I left, I had run out of anything good to give. My battery was drained dry. I had also figured out that Jones was a shrewd and dangerous deceiver, and I was outraged.

One evening in May 1976, while sitting in a Planning Commission Meeting in the wee small hours of the night listening to Jones’ rant against something that displeased him, the thought came strongly in my mind, “You came here to learn how to love, and he is teaching you how to hate!!” That was a moment of blinding clarity.

In the midst of this turmoil, I received the only message in actual words from my Inner Guidance. In early July 1976, it said, “If you leave, do it by the 15th.” It was clearly my decision, but if I left, it specified a date. I did decide to leave, and made careful plans for my getaway. I arrived at the bus station in San Franisco before midnight on July 15, and boarded the next Greyhound Bus for Santa Rosa. No one was there too pick me up at 3:00 a.m. While a Temple member, I wasn’t allowed to smoke, but I stopped at a convenience store to buy a pack of cigarettes, and high on nicotine, I walked almost two miles down deserted streets to the Sonoma County Fairgrounds on the outskirts of town. It was a warm, moonlit night, but dogs were barking in a threatening manner, and I was scared that I might have been followed by Temple members who would drag me back to an ugly scene in San Francisco, or perhaps even murder me. It was a walk of abject terror! I finally succeeded in locating the camper of my friends, who I had known in pre-Temple days, and soon thereafter, I flew to my parent’s home in Ohio.

Thus began my process of rethinking the direction of my life. Although a former Temple member, I had not abandoned the ideals of unity and justice for all, or a vision of a more whole society. My passion for service fueled my return to graduate school so I could better serve Temple members when they left the debacle that was Jim Jones in his drugged state.

After my return to Ohio, I immediately enrolled in a master’s degree program in counseling. My intention was to prepare myself to help with deprogramming members when they left the Temple after its collapse, which I believed was imminent because of Jones’ increasingly bizarre behavior due to his drug use. I called my husband Bob on October 2, which was our second wedding anniversary, to tell him where I was and to invite him to join me. On October 5, I received a call from Carol, Bob’s sister, telling me he was dead! He had been killed while at work in the Southern Pacific Railroad yard. My first thought was that he had been murdered, which was never proven, although I hired an attorney to investigate the matter. I was devastated, because I had high hopes that Bob was about to bring his two daughters and join me so we could begin a “normal” life together. I attended his funeral in San Francisco, which was terrifying because I was a “traitor” and was really scared there might be trouble. Afterwards, I returned to Ohio and completed my college courses. Then in July 1977 I returned to San Francisco, where I got a job in a law firm and hung out with ex-members of the Temple, which included three of my best friends.

Neva Hargrave Sly was a totally devoted, enthusiastic Temple member for eight years and had been the administrator of a boys’ commune while also running the publications printing press. After being transferred from Redwood Valley to San Francisco to get a paying job, she became a member of our Potrero Hill Commune. Besides being one of our favorite cooks (although all the women competed for time in the kitchen), she became the official hair cutter. We all enjoyed her presence, especially the kids. In March 1976 she was “rewarded” by Jones who ordered her publicly beaten with a rubber hose for the “crime” of smoking a cigarette. She went to work the next day, where horrified co-workers saw her dark bruises and raised welts. They found her an apartment where she kept a low profile until Jones left the U.S. I had no idea where she was for weeks, but since I was in my own process of disengaging, I didn’t have much time to be concerned about her safety. We had lived and worked closely together while in the Temple, and she remains a dear friend to this day. She lost her husband and son in Jonestown.

I shared an apartment with Garry Lambrev, a Stanford-educated political activist and long-time friend. He left the Temple in August 1976 and was also working to detach himself from the hold Jim Jones had over him for more than a decade. He was pivotal in helping me and others accept the truth of our perceptions about Jim Jones and his escalating madness, or drug-induced psychosis. We were not disloyal traitors because we quit the Temple; Jim Jones had betrayed us!!

Liz Forman Schwartz, the daughter of a famous Hollywood screenwriter, and a loyal Temple member for seven years, was a shining light of tender loving care in her work of finding housing for seniors during our out-of-town bus trips. She also left in August 1976, and was a steadying force during this chaotic, confusing time.

There was our group, and the most important service we could perform for each other was active listening. Who else could we share our incredible stories with, but each other?

In July 1978, I moved to Los Angeles to work with the Human Freedom Center (HFC) to prepare for an influx of Temple members from Jonestown who we anticipated would be defecting and returning to the U.S. at any moment.

I did not have enough money to fly with Concerned Relatives to Jonestown with Rep. Leo Ryan to investigate abuse allegations. But I was planning to go on the second mission because, knowing Jones, I was certain this first trip would be a total failure and that we would have to return.

Jonestown Massacre – November 18, 1978

No one – no one – anticipated anything even remotely like what happened in Jonestown. At first four hundred bodies were reported, and for a moment those of us waiting for news in California hoped many had escaped into the jungle. Then suddenly reports stated more than nine hundred bodies were found!! Who could imagine such devastation?

Temple members working at the San Francisco headquarters conducting Jonestown business were as stunned as ex-Temple members like me working with the HFC. We had been in touch with relatives and friends who had loved ones in Guyana. We had concerns about the mass move to Guyana and were relieved when the Concerned Relatives and Congressman Ryan undertook the mission to visit Jonestown. But we were certainly not worried about a massacre.

Choosing to leave Peoples Temple turned out to have been my monumental decision.

Had I not left, I surely would have died in Jonestown. My voice and memories would not be here to add to the voices impacted by the Peoples Temple social experiment and this horrible and historic event. All of our stories are important. The story of how the Massacre came into being needs to be understood – deeply understood – as part of our human story on the personal, familial and cultural level.

After the news of the Jonestown Massacre made international headlines, the HFC in Los Angeles became the hub of information for Temple members, families and the media. Our phone was constantly ringing as freaked-out relatives and friends of people living in Jonestown called frantic to get any news of their loved ones. We did our best to console callers. It took time for the bodies to be identified and lists of the dead compiled. To assist the process, I had to procure the dental records of my stepdaughters and the six children for whom I had legal guardianship! There were still a few active Temple members remaining at the San Francisco headquarters, but because the HFC had been working with Concerned Relatives, we were considered a more relevant source of information. We gave interviews to the many reporters swarming around, but were unnerved to see our stories twisted into unrecognizable lurid narratives. One story reported that my husband, Bob Houston, had committed suicide by jumping under the train!

Even while I was still reeling from the loss of many dear friends and children, I accepted an invitation to be on the Pat Robertson’s 700 Club. I considered him a self-righteous charlatan, but my Inner Guidance indicated I should go. It was a difficult experience, because they were trying to demonize Jones and fit the tragic event into their narrow fundamentalist-Christian perspective of Satan’s forces. Their story was not my story – and my story was inconceivable.

My beloved Temple Family was murdered and I experienced a shattering of my soul. For all the trauma, I never saw one body. I was in California. However, of fourteen children I lived with in the commune on Potrero Hill, ten died, including my two lovely stepdaughters.

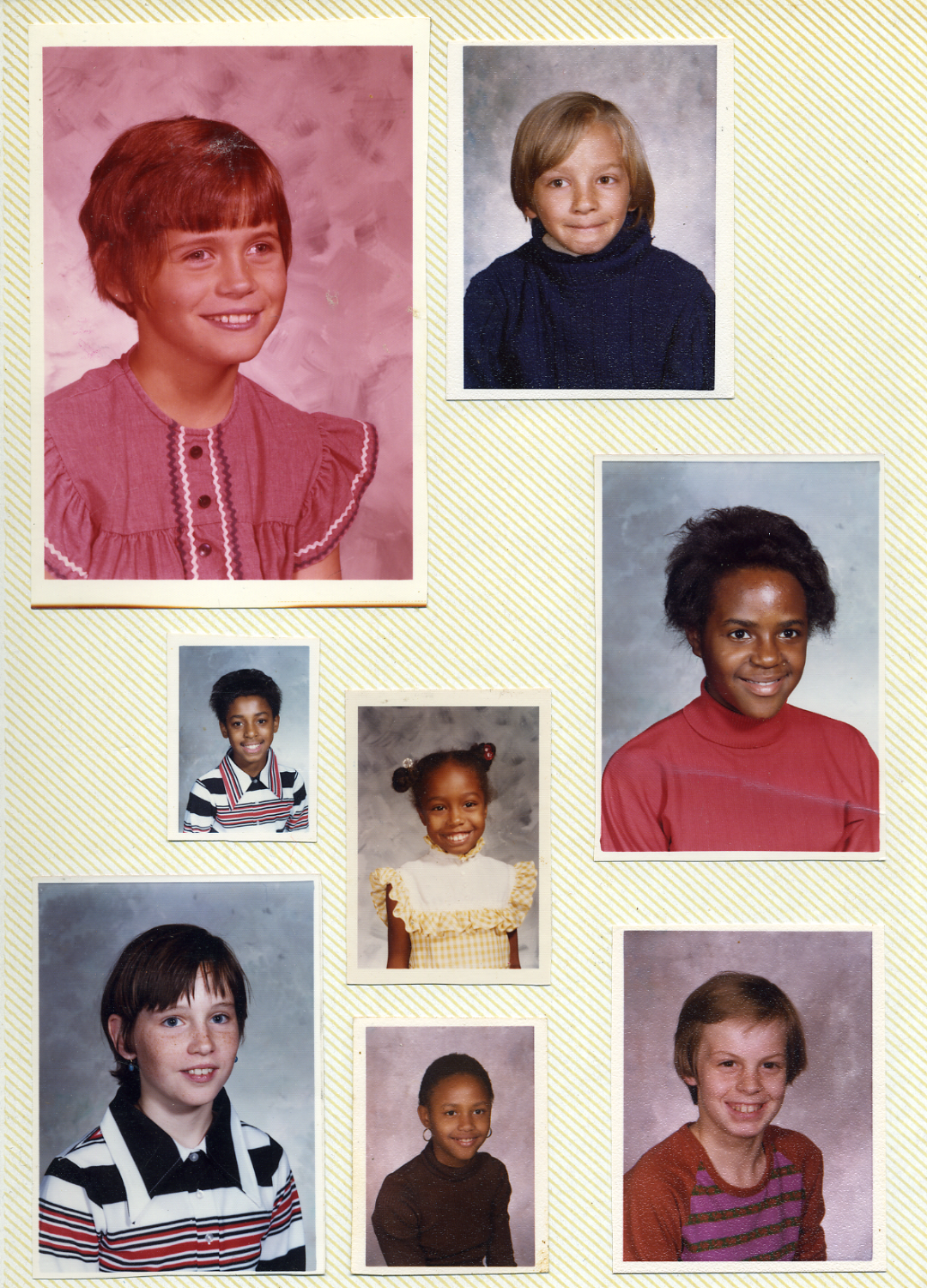

- Nicky Lawrence (b 10-16-62), 2. Odesta Buckley (b 11-30-62), 3. Patricia Houston (b 10-2-63), 4. Dee Dee Lawrence (b 12-31-63), 5. Judy Houston (b 11-9-64), 6. Frances Buckley (b 11-18-64), 7. Jim Arthur Bishop Jones (b 11-25-64), 8. Kelin Kirtas Smith (b 3-4-65), 9. Tracy Stone (b 2-3-66), 10. Lerna Jones (b 1-19-69). The four survivors are: Vonn F. Smith, 2. Sue Hess, 3. Sharon Hess, 4. Hugh Doswell.

Of the adults from Potrero Hill, Brenda Brown Jones (b 12-13-48) and Teresa King (b 1-11-47) both died. Vern Gosney was shot on the tarmac at Port Kaituma and nearly died; he survived but his son Mark did not. David Galley and Sue Ellen Williams survived but lost their son, Will. Neva Hargrave Sly survived but lost her husband, Don, and son, Mark. Vivian Pennywell Gainous survived by not going to Jonestown, as did I. Bob Houston had died earlier in 1976.

Three hundred children died at Jonestown. These were the children who ran around the rooms while we ate, who played with each other at picnics after Temple services, and who sang songs on the bus trips to Los Angeles. I watched them grow up. Of the more than nine hundred people who died, I figure I knew six hundred directly. These people were my family and my community.

All this activity with the HFC kept me busy and distracted during those first days and weeks while I was in complete shock. For at least the first year, I trod lightly, because it felt like if I stepped too hard, my mind would fly away and never return. My body ached all over. If I had a massage, the pain would return within an hour. I slept on the couches of friends, but slowly started rebuilding my life. I got an apartment in the Hollywood Hills and a job at a law firm in Century City. I worked as much overtime as possible to keep busy.

Comments on Conspiracy Theories

Peoples Temple openly called itself a socialist movement. Thus, we were a revolutionary group and Jones a dangerous leader. At the end, as reported in the New York Times on November 28, 1978, Jones considered moving the Jonestown people and large sums of money to Russia. Such a move was calculated to make a dramatic statement about the failure of democracy. Given the political climate of that time, it is entirely likely that Peoples Temple was considered a threat to be eliminated.

I would like to comment on Mark Lane’s book, The Strongest Poison, released in 1980 by Hawthorn Books, a division of Elsevier-Dutton. Lane makes a compelling case that U.S. government forces were involved in the Jonestown Massacre. His book was written in collaboration with Terri Buford, who ranked second to Jim Jones before she “defected” a few weeks before the massacre. It is well-researched and sourced, and everything that is alleged therein fits in with what I know about Jones and his inner circle, and from people with whom I have talked in the intervening years. Those of us who lived through this era were witness to the U.S. government’s ruthlessness in suppressing any individual or group it considered opposed to its concept of “democracy.” African-American groups were especially targeted, and scores of Black militant leaders were gunned down or imprisoned. Anyone with a knowledge of the history of the ’60s and ’70s is aware of this.

I also refer you to In My Father’s House: The Story of the Layton Family and the Reverend Jim Jones, written by Min S. Yee and Thomas N. Layton, with Deborah Layton, Laurence L. Layton, and Annalisa Layton Valentine; Holt, Rinehart and Winston/New York, 1981, and Seductive Poison: A Jonestown Survivor’s Story of Life and Death in the Peoples Temple, by Deborah Layton, an Anchor Book published by Doubleday, New York, 1998. The latter is a brilliant account of the dynamics of “a cult state-of-mind,” which resonates deeply with my own experience. The information contained therein makes the case that Jones’ story of outside forces preparing to attack and exterminate the inhabitants of Jonestown was to Deborah Layton only a very effective mind control technique that psychologically primed them to commit mass suicide. I do not believe this is necessarily a contradiction of the story told in The Strongest Poison. Could Jones’ paranoia have had a basis in fact, and was his descent into madness fueled by his own involvement in clandestine U.S. government agencies?

There was a lot of discussion among us survivors about whether Jones himself was an undercover government agent whose mission it was to do as much damage as possible to the concept that socialism is a better form of government than democracy. If he played that role, he did a brilliant job of sullying the name of socialism by making it look like the “crazy socialists” at Jonestown killed themselves because they were so miserable living in this system. The truth (contrary to what Jones’ told them) is they were living in a totalitarian dictatorship, which is on the other side of the political spectrum.

Another theory is that Jones as CIA agent was conducting an experiment to see whether people could be brainwashed into killing themselves. African-Americans were used because they are “expendable,” and their deaths would not cause such a loud outcry that extensive investigations would have to be carried out. (How true that has proven to be!) In this scenario Jones would have walked away from the killing field and begun a new undercover life abroad. However, Jones’ behavior became increasingly erratic due to drugs. He became a “loose cannon” who could no longer be controlled, and so was shot and died at the pavilion with those he had betrayed.

Jones spoke from the pulpit many times about leaving his small congregation in Indianapolis in about 1960-61 and traveling with his family to Bela Horizonte, Brazil to do missionary work with impoverished children there. He used to brag that he had become the lover of the wife of a high-ranking government official (with Marceline’s permission, of course!) to raise funds for feeding the children. It was told to me that when Jones returned from Brazil, he suddenly had money, and then moved the entire church to Redwood Valley, California in 1965. I still wonder about it.

He also announced from time to time that there was a government informant in our midst at the very highest level, and we would all be shocked if we knew who it was. I had a fleeting thought about it being Jim Jones himself. Of course, I quickly crammed that thought back into my subconscious.

I talked at length with people from the delegation of Concerned Relatives, including my sister-in-law, Carol Houston Boyd, who accompanied Rep. Leo Ryan to investigate abuse allegations at Jonestown. They told me that while hiding out in the jungle at the Port Kaituma airstrip waiting for rescue after the murders of Rep. Ryan and four others, they heard the sound of gunshots throughout the night.

It is difficult to believe that hundreds of people, particularly the young, would stand around for hours waiting to die a death that entailed gasping for air, convulsing and foaming at the mouth. Even though surrounded by armed Temple guards, surely some would have tried to escape into the jungle, preferring death by bullet to poison. The question for me is whether these guards were capable of shooting family and friends at point-blank range. Even if they were, the odds are still that some would have escaped and been found later. An alternative theory is that either U.S. or Guyanese armed forces were stationed at the perimeters to shoot anyone fleeing from the vat of poisoned Kool-Aid.

I discuss these theories and the questions they raise, because they still float around in my mind after 40 years. I strongly suspect there are elements of truth in all the aforementioned theories. I have not stayed current with the investigations into conspiracy, but feel certain if anything definitive had been uncovered, I would have heard or read about it by now. Ultimately, it does not matter who massacred them. No matter who the perpetrators were, they all died!!

Reflections

Truly, dying with my Temple family would have been far easier than living with the trauma of their deaths, and my role in them. I came to realize that through supporting the Cause, I unwittingly empowered Jones, and thus his ability to commit mass murder.

Had the Temple experience not ended in such a horrifying manner, I would have viewed it as a particularly positive and enriching part of my young adult life. (And I think it is important to remember this was a movement of young people.) I would have felt a sense of pride that I had been part of the early Civil Rights Movement. Afro- and Anglo-Americans actually lived and worked in the Temple, up close and personal, as equals in harmony to promote a society that gives everyone the opportunity to achieve the American Dream. Our culture was so segregated in the 60’s and 70’s, it is difficult to understand how extremely radical our lifestyle was.

Being a part of Peoples Temple was brutal in terms of personal self-interest, that is my ego, but exalted in terms of my youthful perception of service to humanity. It was both the hardest thing I ever did and the most fulfilling. I said then, that after this experience, nothing in my life would be anywhere near as difficult again. So far I have been correct, even in the depths of my healing from the trauma of the Massacre.

Recovery from my Temple experience, or more accurately, from the Massacre, included years of psychological counseling. I am diagnosed with PTSD and severe reactions of withdrawal and depression descend whenever I open the door to this period of my life. I rethought my views on the universal laws that govern how the cosmos works. Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. were totally correct in advocating peaceful protest as a means of social change. The ends do not justify the means. The means determine the end.

In order to emotionally integrate the survivor’s guilt of such a traumatic experience, I re-examined all aspects of my own cosmology and theology trying to account for humans behaving in such inhuman ways. I knew that without a strong spiritual belief system based on love, I would become a bitter, cynical and hate-filled person. After all, I had the best possible excuse to play the ultimate victim. At the time, I considered victims to be weaklings, and did not want to be seen in that light.

The oldest game in town is “blame the victim,” and I myself assumed responsibility that wasn’t mine. In fact it wasn’t until 1992, when I joined a support group called “Family and Friends of Victims of Violent Crimes,” that I actually thought of myself in those terms. The world press had been very consistent in blaming us survivors for having been stupid\gullible\sick\naive enough to join a cult, so we were to blame for our plight.

Another difficult issue that arises whenever I mentioned my affiliation with Peoples Temple and Jonestown are the reactions of other people. Almost invariably, a look of horror crossed their faces, followed by a gasp and a hurried “I’m sorry.” Too often I ended up comforting and reassuring them that I am okay. I felt cut-off, isolated and alone. Then – almost without exception – they informed me they would never join a cult!

Oh? The fact is No one joins a cult. It becomes a cult. As time goes on, and more and more adulation, control and power is concentrated into the hands of one individual who is accorded religious veneration and devotion. In other words, one has given one’s power to a fallible human being who invariably misuses this power because s/he is a fallible human being.

People who feel exempt from being drawn into a cult are naïve and don’t know much about human nature. Importantly, what is not mentioned about folks who join what turns into a “cult,” is that they are usually kind-hearted, compassionate people who want to make our collective life on Earth better and are willing to volunteer their services with that goal in mind.

And I ask, since when has searching for greater meaning in one’s life through service been a bad thing? Deep inside each human, there is a longing to return to Source and Love. This longing has been exploited for millennia by religions, governments, and other types of “-isms,” which purport to know the steps it takes to achieve this return. The unscrupulous psychopaths who focus on exploiting others for their profit in the name of god and religion become our “teachers.” Through them we learn to discern the truly loving from the deceivers. We do this by listening to an Inner Guidance, a still small voice within, that each of us possesses.

Life Goes On

About two years after the Massacre, I met Rodney Carr-Smith, a British artist and writer, who was the biggest distraction ever!! When he moved to the San Juan Islands, I soon followed to Seattle in August 1981, and we were married a year later. After a stormy four-year marriage involving a lot of alcohol, we divorced. In November 1986, I moved to the Port Madison Indian Reservation in Suquamish. I bought a tiny cottage near the beach with a view of Mount Rainier. It has been my refuge for the past 32 years. I have a green thumb and love working in my yard. Physical activity diffuses my anxiety, and beautiful flowers soothe my soul.

The Native Americans here are a peaceful, kindly, loving people, who are also shrewd businesspersons when presented with opportunities. Their culture barely survived a “soul murder.” Many took refuge in drugs and alcohol, but as they recover, they understand the necessity of helping each other, especially their elders and children. They look to the Seventh Generation when managing their natural resources, which results in a respect for Mother Earth that becomes a nourishing and integral part of their beings.

My heart thrills during the annual Northwest Canoe Journey, when more than a hundred traditional canoes arrive from as far away as British Columbia and land on the Suquamish beach. Thousands of Natives and well-wishers gather to feast and once again enact their traditional ways. No one is exalted, excluded, shamed, or ignored. What a blessing to live among these lovely human beings for whom I have such great respect.

During the first three years in my cottage, I commuted by ferry to work in a Seattle law firm. I was smoking a lot of pot, and my life started to fall apart (again!). I quit my job and for a brief time sold frozen lobster tails out of the back of my van. Then I lived on unemployment. By this time I had been diagnosed with PTSD, and a claim for disability was under consideration.

Recovery

On May 6, 1991, five years after I arrived on the Kitsap Peninsula and a full thirteen years after Jonestown, I began a twelve-step program for alcohol and marijuana abuse. Shortly after beginning recovery, I had what used to be called a “nervous breakdown.”

It was my dark night of the soul and lasted about three years. I was sorry that I had not died in Jonestown. I struggled daily with intense, suicidal thoughts that I succeeded in not acting on because of the trauma I knew it would cause my family. I had seen too many families in grief and despair after Jonestown and could not bear the thought of inflicting such pain on my family.

This 12-step program literally saved my life and answered my needs perfectly. It is essentially a spiritual program providing a skeleton or structure of principles and practices onto which one can graft any spiritual content. After 27 years of continuously working 12-step programs and going to several thousand meetings, I consider the folks there to be members of my tribe. Probably because they have been through the hell of addiction, which often includes outrageous behavior, they accept me and my far-out story, and treat me like any other recovering person.

Most importantly to me, 12-step programs are not hierarchical. There are no leaders who can abuse power, only “trusted servants” doing the work necessary to keep meetings open. I chuckle when new members share that they initially thought AA or NA was a cult. We are the antithesis of a cult. A cult cannot exist unless there is a leader who followers can exalt and give their power to. If anyone in a 12-step meeting tries to dominate, members can simply quit that meeting and move to another one. Thankfully, there are plenty to choose from.

After my experience with Jim Jones, I was leery of getting close to people and involved in organizations. But as a human, I need community and social networks. In addition to 12-step programs, I attend a New Thought church, Unity, which has beliefs that for the most part mirror my own. It accepts all people as reflections of divine love and all faiths as being valid paths up the mountain leading to the same place. I work on maintaining a positive attitude on a daily basis, because my ego conspires to make me forget to trust my Higher Power which in turn leads me to spiraling down into negativity.

I was born with a lot of compassion and empathy, and don’t remember ever consciously trying to hurt someone out of a motive of revenge. That being said, I am a limited human being and get mad and react if I am pressured too much. But through the Temple experience, I learned my physical and emotional limits. I still wrestle with the issue of helping those in need. We each have a Higher Power and are responsible for our own lives, but we all need the help of others. Where does one draw the line? Theory is one thing, but practical application is another. Through my own recovery, I know my best course is to tune into my Inner Guidance when these situations arise.

After Jonestown, I made it my policy to help only those who actually showed up on my doorstep. A number have done so, but these have been staggered out over the years and are thus manageable. Four Native-American children lived with me part-time for three years while their parents recovered from drugs and alcohol. The four children later became drug abusers themselves, but are all now in recovery. They are beautiful, loving young adults who have been major lights in my life.

Spiritual Principles

My healing process has been guided by two major spiritual principles: a belief in reincarnation, and that, “Everything is unfolding perfectly in God/Goddess/Great Spirit’s Universe.” I arrived at my belief in reincarnation after pondering the pros and cons of it for a number of years. I ultimately concluded that only reincarnation can begin to explain the mysteries of our life on Earth.

In this theory, each human possesses an immortal soul at the center of which is a divine spark from the Creator whose essence is love. It is said that Earth is a school where we are learning to be Embodied Spirit. This is exceptionally challenging, because our physical bodies are a cross between a primate or animal part which operates on the survival principle “eat or be eaten” and Divine Spirit which has a love essence that we are learning to express.

Over the course of many lifetimes, we have every kind of experience in every kind of culture as both men and woman, in various relationships, etc. The ultimate goal is to learn to love and accept humankind, and to live a life reflecting compassion and empathy for our human family.

From a reincarnation standpoint, there are many ways of looking at a particular life. One point of view is the idea that because I was part of Peoples Temple, I was being punished for some past “sin.” I sense that in many past lives I was a warrior. If I had participated in military raids where villages were torched and entire communities slaughtered, then a very effective way to learn the emotional consequences of that behavior would be to lose the members of my “village,” which was Peoples Temple.

This is one scenario. Another could be that we return to the Earth plane to accomplish a particular mission. I believe that many people at Jonestown decided before reincarnating to sacrifice themselves so that, through their dramatic and horrific deaths, the world would be shocked enough to learn about the dangers of cults. Perhaps my role was as a nurturing person who made some of the children’s time in Peoples Temple more bearable. Perhaps living and learning after this debacle was my mission, too. This might explain why I did not die in Jonestown. It wasn’t part of my mission. I believe all scenarios are potentially true.

We humans have much to learn about love in this Earth school, and hopefully we can cram lessons on many different levels into one life. Of course, I have no proof about the validity of these hypothesizes, but they help me reconcile the Jonestown Massacre with my affirmation that the universe is fundamentally a loving place. I am comforted in believing that we live in a universe with order and meaning. Our lives do not consist of a series of random events, and then we die!

Additionally, there is the fact that as the years go by and I follow my Inner Guidance, my life unfolds in a beautiful way that I do not believe would have been possible through “rational” decisions made with my “monkey-mind.” I know for a fact that this “monkey-mind” is capable of rationalizing anything. Therefore, I must always gauge the truth of any thought or belief against a standard of love, kindness, compassion and the “Golden Rule.”

Given my belief in reincarnation, I fully accept that I chose both the family into which I was born, and my eventual joining of Peoples Temple. I talk at some length in my 1980 interview with Tim Reiterman that I was not eager to become a member, but felt an inner compulsion that I eventually succumbed to. I have a strong ego that believes it is in charge and can run its life without any help from a Higher Power, thank you very much. I am too smart for my own good. Perhaps it took an experience like Jonestown to bring me to my knees and start me on a spiritual journey in which I give obedience to my Inner Guidance, not the outer world.

Along with reincarnation, my core belief is that “Everything is unfolding perfectly.” To the extent this is true, there are no victims and no perpetrators or heroes. Each of us lives out circumstances which perfectly reflect our state of being and the lessons we are learning. In this view, we must be-here-now. No one to blame. No excuses. No escape routes. The only way through is by listening and following the promptings of our Inner Guidance. By taking the next indicated step, one at a time, we extricate ourselves from unpleasant circumstances and states of mind and (re)build lives meaningful to us so we arrive at inner peace and serenity. There is no glamour, applause or drum roll from “out there” that equals our “inner” rightness. It is as simple as one day awakening and realizing that Life is Good. We remain in this heightened state by focusing on the positive, serving our brothers and sisters and listening for Inner Guidance. It is a wonderful way to live and gives me peace of mind.

Happy Memories

As discussed before, I wanted to have children but, my husband-to-be, Bob Houston, had a vasectomy a few weeks before I met him because Temple policy was against having children when there were so many unwanted children in the world. If a member desired children, then adoption was the choice. I was completely happy to help Bob raise his two daughters and other Temple parents raise theirs. The children’s commune worked for me.

I had an extraordinary experience as head of the Children’s Commune on Potrero Hill with the fourteen children and nine adults who lived there. I would go through the entire experience again just to share those 18 months with those wonderful people. We were grateful for our lovely house and its beautiful surroundings. Most importantly, we created a home filled with love and appreciation for each other. The adults felt the satisfaction of helping the children who thrived, did well in school and enjoyed their time playing together. We shared a lot of fun times.

We were all wounded in one way or another, but maybe that is what called us to Peoples Temple and the idealism we found there. Maybe our pain opened us up and made us willing to pitch in and work for a vision of a more just and equal society. Unfortunately, Temple rules increasingly hampered our good family life, but we created one and a half magical years!

My Legacy

It is difficult to be objective enough to know what my legacy might be. Today, in my elderhood, I am incredibly grateful to be alive. I learned so much about life and healing through this experience. Much of it is beyond words. I am really enjoying my life and having a good time – which is perhaps a living legacy for those who didn’t live.

I have learned that when we are caught in horrible positions or situations beyond our control, our responses matter. One can display great courage and resiliency from a seeming position of weakness, and then move beyond it. The late Senator John McCain is a sterling example of this. I have been inspired by Herman Hesse’s sentiment: “I have always believed, and I still believe, that whatever good or bad fortune may come our way, we can always give it meaning and transform it into something of value.”

I survived to be a witness to the evolution of Peoples Temple from its early days in a small rural community in northern California to its expansion in the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles, and then to its final destruction in Jonestown.

I have come to understand that when a line is drawn between “us” and “them,” where “we” are the “good” folks and “they” are the “bad” folks, we’ve moved into judgment, anger, prejudice and failure to take responsibility for our own thoughts and actions. In other words, ego has taken over and love has departed.

One of the aspects of leaving the Temple that tormented me for years was the thought that Temple members, and especially members of my commune who went to Jonestown, believed I had abandoned them as well as the idealistic principles we stood for. I have always remained true to the ideals; it was a personal awakening that forced me to leave.

I can describe the mental process I went through as I was first hooked by Jones’ message, my decision to join, my six-year experience of life inside the group, and my eventual decision to leave, as well as the shock of the Massacre and the very long road of healing from the trauma. Although there will always be deep scars, the good news is that I am healed enough to wake up in the morning enthused about the coming day and what it will bring. I have retained my “dry” sense of humor, and I love to laugh, which I do – often at myself.

I have healed from the trauma of my childhood. I have come to empathize with my father’s background and feel compassion for him, even though I do not excuse his abuse. Two years ago, through genealogy – which is a great love of mine – and DNA, I found out who his biological father was. He was a widower and well-digger who came from a respected West Virginia family with roots back to the Revolutionary War. After his wife died, he got several local women pregnant, much to the chagrin of his mother and other family members. He later got “saved,” but never atoned for begetting my father and the pain he caused my Dad and his descendants by not acknowledging him and being part of his life.

By the time my mother died at the age of 95 in 2014, I had come to adore her. As she aged, she began to speak up and think for herself. She was a gentle, loving and gracious soul, and I spent a lot of time with her in her later years. It turns out I had resented all the attention she focused on my Dad, and after he was gone, I was able to have her to myself. I also love my brother, Phill Cable, and my sister and brother-in-law, Jeanne and Larry Hauf. They do not share my political or spiritual beliefs, but I have learned that love is what ultimately counts.

My niece, Jennifer, and her husband, Nathan, have three delightful children: Alex, Madison and Savannah, whom I adore. I typically spend at least a month every holiday season in Ohio where they live. I used to hate Christmas, focusing on its commercial nature, but I now enjoy the good cheer and togetherness. I make no attempt to impose my beliefs on them. It is not my place. I am blessed to play “second grandma.” The children sense my free spirit, and we totally enjoy playing and having fun experiences. They love me and bring me much joy, which is all I could ever desire.

I have only attended the 20th anniversary and memorial service and have not been involved in the Jonestown Institute gatherings hosted by Fielding (Mac) McGehee and Rebecca Moore. I wanted to, but could not because of the PTSD reactions whenever I touched anything to do with Jonestown. I started many articles, but could never complete them. As the 40th anniversary approaches, my Inner Guidance made it clear that I was to write about my experience for the jonestown report. I asked my Higher Power for the strength to complete this article. I hope to be a channel for whatever information that I am to convey. My appeal was answered when a writer\editor spiritual friend, Suzanne O’Clair, supported me in myriad ways. Through this writing process, I see my conduct in the Temple in a new and more positive light. For the most part, I remained true to my humanitarian principles of being a kind, sharing person. Then we were instructed to focus on our shortcomings and confess them. Today, I am allowing myself to focus on my positive aspects. I stayed true to my values under extraordinarily difficult circumstances, and there is immense strength in that. I can’t explain it, but a sense of dignity has been restored to me as I complete this assignment. I escaped while still in the U.S., so I do not know how I would have behaved under the conditions described in Seductive Poison. I stood up to Jones for my children’s rights while in San Francisco; would I have done so in the Jonestown prison camp? I hope I am never in such a position. If I am, I will listen for the still small voice and I will know what to do.

From my perspective, I believe I have made progress in Earth School. I once aspired to a grand sophisticated life out in the world, but have found my place in a small community living a simple life with many good friends who accept me just as I am. I have a loving relationship with my family and cherish them. I have definitely learned more about love, and that is ultimately what life is all about.

In writing this article, I have now told my story.