I was the last guest in Jonestown.

I visited Jonestown just before the collective suicide took place, as the only foreigner who came into the camp and met Jim Jones without having had any earlier connections with Peoples Temple. Eleven days later, Congressman Leo Ryan arrived at the community with his entourage, and by the end of the following day, 918 people were dead.

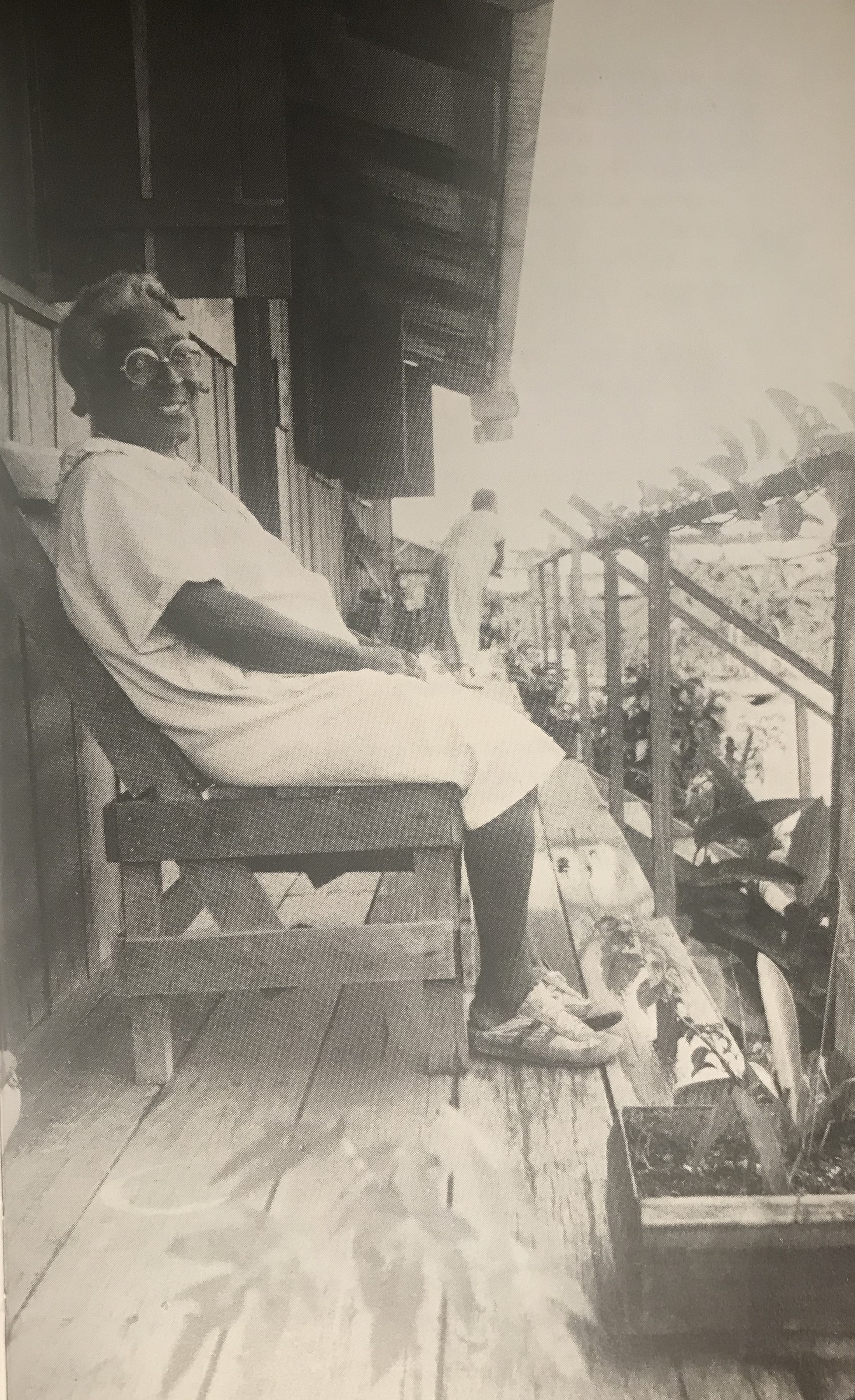

I remember isolated details of my time there more than a larger coherent narrative: the moist heat of the jungle, the birds singing at sunset, and above all the people, their smiles and their warm and unreserved welcome. I was given the opportunity to take some photos, and I look at them occasionally and remember how well I felt in their company. I came very close to ask for their permission to stay among them one or two more weeks. That would probably have cost my life.

In the 40 years that have passed since my visit, I have refused to tell about my stay. I wanted to keep the memories for myself. Others should not be allowed the possibility to contaminate the happiness I experienced in Jonestown by telling stories about the massacre. I wanted to have Jonestown for myself.

While that acknowledgment of the Jonestown people is a very private matter for me, I am ashamed not to have seen and understood the massacre. And perhaps I was seduced as well, not to see what was coming. That is why I write now.

The arrival in Jonestown

The background for my visit was that I had made a film about an Indian tribe in Latin America with photographer Morten Bruus. He had met the lawyer Charles Garry and some Peoples Temple members in New York, after they contacted him about a proposal to make a film on Peoples Temple. Morten Bruus passed the invitation on to me, and when I happened to be in Venezuela, I made a side trip to neighboring Guyana. In short, it was a series of coincidences and happenstances that brought me – a foreigner with no prior knowledge of Peoples Temple – into Jonestown.

I took a small Cessna flight from Georgetown to Matthews Ridge and flew over the densest jungle I had ever seen. From the little airstrip, I was driven in a four-wheel truck for a couple of hours to the entrance of Jonestown. An elderly married couple stationed there became very nervous that I had just arrived without warning or invitation, and wanted to visit the camp. Without specific permission, they explained, no stranger could come in. Even though I was alone, they insisted that I go to the nearest village and wait for instructions.

Mobile phones were in their infancy, but with a cellular radio connection they contacted Jim Jones, who in turn called Charles Garry, who recommended that I be allowed in. The procedure itself took a couple of hours.

I remember a little episode that I later considered to be very typical of the Jonestown people generosity. They were visibly nervous of having me wait, probably because they thought I was a CIA agent, and they repeatedly told me to move on to the next little settlement before darkness fell. In addition, it was threatening to rain. But despite this rejection, the two elderly people shared their lunch package with me.

After a couple of hours of waiting, we received the message: I would be welcome to visit the camp. A tractor with a trailer arrived to pick me up.

By that time it was getting dark, and it did rain. The camp had sparse lighting, and I could hear a generator. I could also hear Jim Jones talk over a public address system. But people greeted me in a friendly manner, waving and shouting their welcome.

The rain, wet walkways, Jim Jones’ voice over the loudspeaker, the sparse lighting, people walking around mostly alone, talking in groups in a few places: All in all, the camp gave an impression of an unfinished construction site.

The next day, when the sun rose and the rainclouds had cleared, the picture of the camp was entirely changed. Some part of Jonestown was apparently orderly, the jungle had become a garden of tropical flowers, and people walked around with a purpose of going to work. But it was difficult to get any physical overview of the camp, and there were parts of the camp on the periphery that I never did visit.

The constant surveillance

During the two days I was in the camp, I was kept under constant surveillance. One or more selected residents followed me all the time. When I visited the toilet, they waited outside. At night there was always a person sitting outside my room. I always had my camera on me, but I was not allowed to use it. If I wanted to take some pictures, I would ask the guards to take them for me.

Only once was it possible for me to escape the constant monitoring. As I wrote in my diary:

The sunlight is bothering me and I want to fetch my sunglasses in my room. But the guide calls someone standing nearby and asks him to go get them. Insisting on doing it myself and also having to visit the toilet I managed to be alone.

I take the liberty of going the wrong way and ended in a part of the colony l haven’t seen before. There are four large barracks here, and through the windows I see people packed together as tightly as in the slave ships, eighty to a hundred people in bunk beds with less than a meter’s space in between, mostly old people. I don’t take special note of that sight. These living conditions are probably unavoidable when you are building an alternative society.

During the two days I was in Jonestown, I had many conversations with people. Some of the conversations I recorded in my notes. In some cases, after my stay, I found their statements reproduced – exactly as I had heard them. Their words and phrases were obviously read so that they could be repeated.

I eat breakfast with the camp’s leaders. The atmosphere is relaxed and we talk about unimportant matters, the jungle, the heat, and Guyana. While the others are talking, the man sitting next to me introduces himself: Mike Prokes, former filmmaker. He is very interested in talking to me and pulls me aside, asking me about anything and everything. Suddenly, he winks in a knowing way and pinches me in my arm as if we share a secret. It makes me wonder.

Later I find out that Mike Prokes survived the mass suicide and was arrested in Georgetown. I also learned that he shot himself to death about four months later, after he had returned to the States.

The last day I was in the camp, it was as though my presence had become a little cumbersome. What would they have to entertain me with now? The visit to the medical doctor is an example. As a courtesy, I was offered a comprehensive medical examination. I wanted to decline the offer – I was healthy, so there was no need to visit the doctor – but he insisted. At one point, I was asked to take all my clothes off, and when he put his finger in my anus to search for hemorrhoids, I felt defenseless and humiliated.

It was the same doctor who mixed the poison for the suicides 11 days later.

My encounter with Jim Jones

I first spoke with Jim Jones over the telephone in the camp’s radio room just after my arrival. I was told that, for security reasons, he could not meet strangers face to face. Nevertheless we did meet later. He appeared to be under the influence of some drug and said that he had fever due to a stomach infection. He was worn down and tired, speaking in a slow forced manner, as some people do when trying to overcome fatigue.

In my diary I wrote:

Jim Jones tells how difficult it is to establish a socialist movement. Even though they have chosen to give it the religious cover name, Peoples Temple, and have moved to one of the most remote and isolated piaces in Latin America, they are constantly threatened by conspiracies that try to annihilate them. In particular, in April and May of this year, they have been under CIA attack.

Jones says that I would not believe my ears if I heard what experiences of persecution they have had in the jungle. For several weeks, the CIA has had a force of twenty-five to thirty men in the jungle, shooting after them and attempting to poison their food. Jim Jones tells in great detail about the methods used by capitalist conspiracy to get rid of them. I don’t know what to believe.

When Jones finally spoke to me, for about 90 minutes, I attempted to write down as much as possible. He spoke in an endless stream, and in an attempt to make some sense out of his words, I resorted to my profession clinical psychology. The conversation was recorded on tape, and I ask to hear it again, winding forward to two passages, which I then wrote down word for word:

The CIA is using every trick to gain control of me. At times they even control and influence my thoughts, so I cannot think clearly. They have their means, so they poison my food, and that poison also affects my brain activity.

In periods I am so absorbed by the idea of socialism that I really am Lenin and speak with his voice.

Within traditional psychiatry, one would designate such statements as symptoms of paranoid delusions. But I did not pay much attention to them. The diagnostic criteria might be changed in a personal conversation out there in the isolated jungle.

The glory of the Jonestown people

The last night I spent in the camp, almost all the residents gathered in the pavilion. After Jim Jones talked over the speaker, I thanked the people for the stay. I had met so many good people and I was impressed with their efforts to create a better world isolated in the dense jungle. When the Jonestown band, The Jonestown Express, played I was moved.

I was seduced that night by Jonestown. My conversations with the residents have been recorded on cassette tapes. Hearing it now brings me to tears. They are like a revival of some traumatic experiences. It is not so much about what happened and the 918 who died, but rather the awareness that it can happen again, the banality of evil, which we all have a potential to repeat, if as few as three conditions are present:

• A conspiracy theory

• An isolation from the surroundings

• A charismatic leader.

I will never be able to shake off the experience of staying in Jonestown. I have read most of the many articles and books collected on the subject. I gaze at the pictures of the victims. I can recognize some of them I had been with for those two days at the beginning of November 1978. I talked and laughed with several of them about subjects which I no longer remember, but I do remember the talking and laughing.

The massacre took four hours. While the inhabitants waited to receive the poison, some of them took the time to write letters to their families:

They will never be able to destroy what we have built up, because we decided a long time ago that if they come after us, they will have to take all of us together. Martin Luther King said it like this: ”A person who has not found something to die for will not feel he is alive.”

At least we have had the satisfaction of living in justice here. It’s not because they have promised us success or reward, but simply because it was the most right thing to do—the best way we knew of living our lives.

Some of these statements could have come from the mouths of other oppressed people as well. The eradication and destruction of a innocent people could happen again. In a sense, the jungle in Guyana is not so far away.

(Peter Elsass is a D.M.Sci. professor emeritus at University of Copenhagen in Denmark. He may be contacted at Peter.elsass@psy.ku.dk.)