I wish I could say I wrote the kind of “cult novel” every author wants to write – instantly iconic, passed around like a joint, with murmurs of this will blow your mind. Really, I wrote the other kind: a novel that is ostensibly about a cult.

I don’t object to this description. In fact, I resorted to it many times, after getting blank looks in response to my references to Peoples Temple and even to Jonestown. “It’s about a cult,” I explained to drunk people at parties, to the hairdresser, to the elderly doctor prescribing me iron pills. There seemed to be two possible responses to this admission:

- That sounds…dark.

- Oh, I love cult stuff!

It’s a divisive thing, writing a “cult novel”.

* * * * *

Of course, Peoples Temple was more than a cult. It was a community and a social movement, which spanned decades, attracted members from a wide range of backgrounds, and espoused ideals that are just as relevant today as they were forty years ago. This didn’t preclude it from possessing qualities popularly associated with cults – e.g., a charismatic leader, economic and sexual exploitation of members, a violent demise. But certainly, Peoples Temple was about more than these things, just as my novel is.

Of course, Peoples Temple was more than a cult. It was a community and a social movement, which spanned decades, attracted members from a wide range of backgrounds, and espoused ideals that are just as relevant today as they were forty years ago. This didn’t preclude it from possessing qualities popularly associated with cults – e.g., a charismatic leader, economic and sexual exploitation of members, a violent demise. But certainly, Peoples Temple was about more than these things, just as my novel is.

What is Beautiful Revolutionary about, then? It’s about people, generally. More particularly: young, white liberals trying to create a better world, while hindered by their own shortcomings and desires. It’s about sex, power, identity, innocence – its loss and its haunting persistence. It’s about craving meaning in a world that often seems harsh and incomprehensible. It’s about individual unhappiness taking a toll beyond the individual.

All this is very vague and long-winded, though. It doesn’t have the pull of that four-letter word: cult.

* * * * *

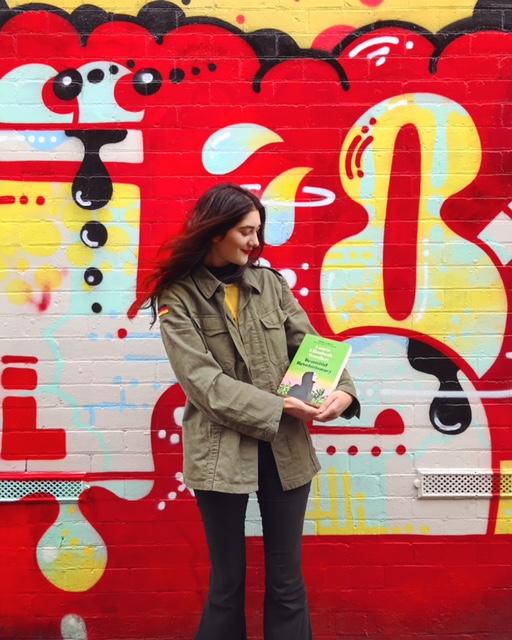

At the time that I’m writing this, Beautiful Revolutionary has been out in Australia and New Zealand for one month, exactly. My publisher has told me that it’s selling “solidly,” but I haven’t asked for numbers, knowing I’ll obsess over them if I do. Other writers have told me they’re hearing good things “everywhere”, but this seems like a polite way of saying they haven’t read it themselves. I try to pretend that the book isn’t my problem anymore, but there’s still a duty to promote it. And I still Google it way too often.

It has been reviewed. Not widely, but enough for me to feel that the reviews are more mixed than rave. Some critics contradict each other while one accuses me of abandoning my main characters halfway through the book, another thinks I spend too much time with them. I read an especially bad review during a visit to my mum’s house, and leave in a huff, headphones on. Concerned, she messages my dad – her ex of twenty-plus years – asking if he’s seen it. Can’t please all the motherfuckers, he replies.

Later that week, he sends me a photo: blurred, off-centre, contextless. It is of Beautiful Revolutionary in the window of a bookshop in my home city.

* * * * *

There’s a certain amount of baggage that comes with writing about historical events, especially when people have preconceived notions about these events. How could so many people fall for that? is a common question. How could one man be so charismatic? is another.

Admittedly, it’s frustrating to see my beloved characters fading into the background, in favor of discussions of how charismatic Jim Jones was and whether I’ve adequately portrayed his charisma. But they’re characters. My frustration can’t compare to what the survivors must feel, seeing their own ideals, experiences, and relationships reduced to one man’s charisma.

Besides, I had similar preconceptions myself, when I first came to this story, years ago. That didn’t stop me from learning more.

* * * * *

As well as reviews, there have been interviews, events. I’m not a confident public speaker, but if there’s a subject I can speak about, it’s Beautiful Revolutionary.

What’s more, audiences seem engaged, and varied. There are young women like myself, interested in true crime, literature, feminism, vintage, or some combination of these things. There are “cult bros,” who tell me they’ve listened to the Death Tape and ask if I’ve heard of The Brian Jonestown Massacre. There are older people who tell me about living on communes in New Zealand, or the cousin who went off the grid and became a Buddhist monk.

I wrote a cult novel. Not the kind every author wants to write, but the kind I wanted to write – I think. Whether it finds a following, remains to be seen.

(Laura Elizabeth Woollett is an Australian writer. Her other piece in this edition of the jonestown report is The Homewrecker. Her collection of articles and stories for the site is here. Visit her website at http://lauraelizabethwoollett.com.)