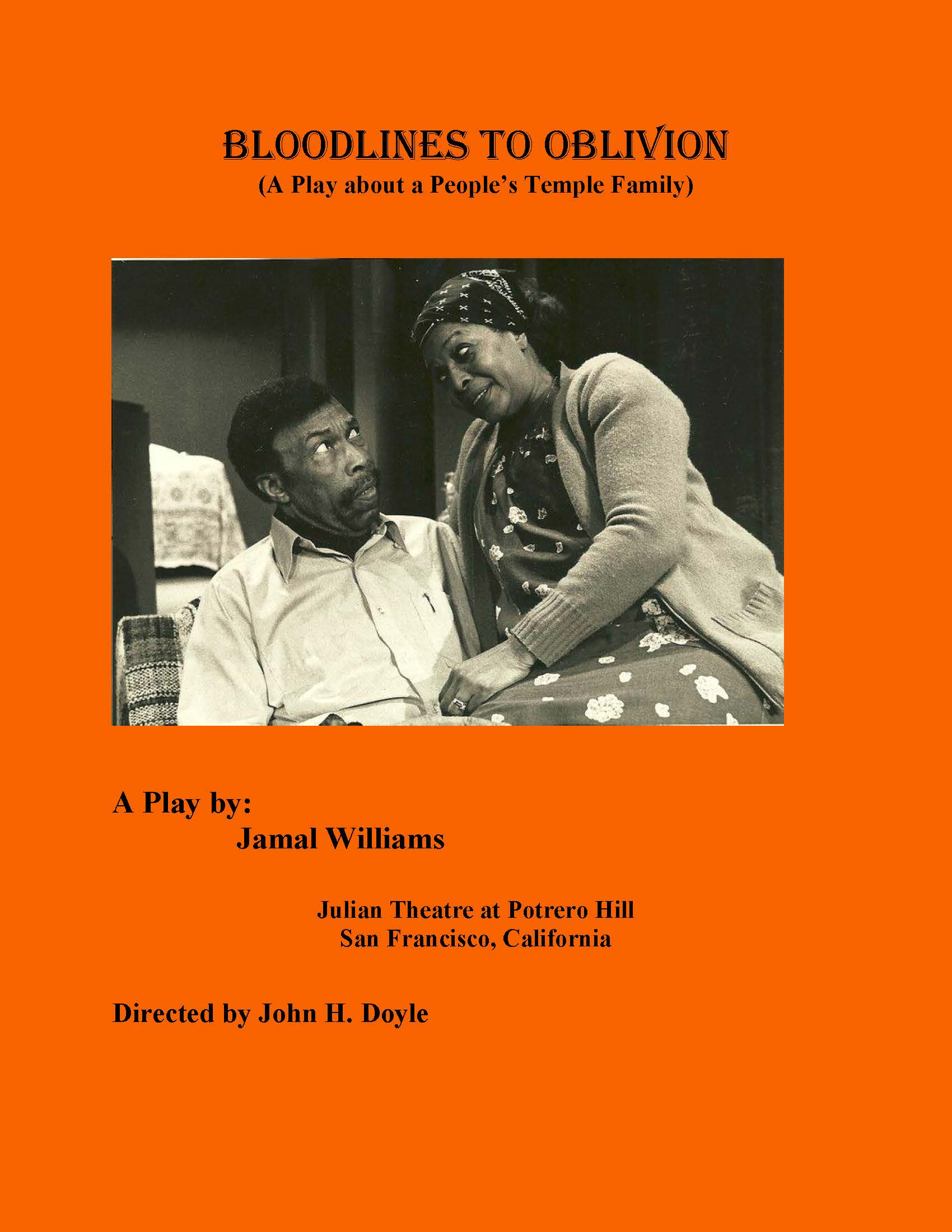

It has been more than 35 years since the 1983 World Premiere of my play, Bloodlines to Oblivion. It’s hard to believe that so much time had passed since my very first produced play opened at San Francisco’s Julian Theatre Company at the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House.

It has been more than 35 years since the 1983 World Premiere of my play, Bloodlines to Oblivion. It’s hard to believe that so much time had passed since my very first produced play opened at San Francisco’s Julian Theatre Company at the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House.

I know that with the passage of time, hindsight is absolute and faithful. Can reflection be 100 percent in the mind of the beholder? And might it be true that the pen is mightier than the sword? I also know for sure that my artistic rendition of this American Tragedy play made quite an impression with many of the so-called Jonestown journalists and scholars who came out to the theater just to see how accurate my impression of the play’s family was in comparison to the real life Temple members who met their tragic fate in the jungle of Guyana. Not that I felt I was writing for their approval, but rather I felt that my first responsibility was to People Temples folks who fervently believed and died because of that belief in the jungle. I felt I owed truth to the survivors and their families’ portrayal, even as I wrote a fictional stage rendition of that historical event.

The play was produced five years after the Jonestown tragedy. Because so much more time has passed, is it possible this playwright can find moments of reflection on my motivation and interest for tackling such a sensitive subject matter as Peoples Temple and its members from San Francisco who went on to their destiny with tragedy in the jungles of Guyana in 1978? Is it possible to recall my drive to turn this real-life event into a work of fiction? Decades later, can I think of a different point of view or plotting in the original writing in which I presented my tragic drama to audiences who probably lost family members in Jonestown?

I now have the advantage of time to help me with my recollections. Things do change with time, but the story of Jonestown is etched in history forever, and the tragedy will always be remembered and examined by historians, psychologists, and students looking for subliminal reasons for mass suicide. Surely it didn’t make much sense that on November 18, 1978, nine hundred and eighteen (mostly black) folks succumbed to the urging of their religious leader, Jim Jones, and committed mass suicide, most by drinking from vats of cyanide-laced fruit punch at the “Utopian” settlement named Jonestown. Nothing can change that fact.

I remember that day in 1978 when I saw the photographs all those bodies on top of each other, bloating in the jungle heat. It really hurt when I later found out mothers gave cyanide and Valium-laced poisoned Flavor Aid to their kids and babies. (Flavor Aid is a British version of Kool-Aid, and in fact, the expression “drinking the Kool-Aid” is a reference to the Jonestown tragedy.) How could religion end up so perverted that liberal white and black folks could buy into this madness so easily?

As a curious young man and a new playwright, as well as a longtime member of the San Francisco community from which most of these people came, I was befuddled to say the least. Tragedy is the opioid of a curious and creative mind. I think the thing that really caused me to write a play about the event and to pick that (family) point of view, was that I actually had a girlfriend who lived in a foster home that had as the matriarch a fervent middle-class black woman who was a believer of Jim Jones. Many times when we would hang out, she would try to convince me to spend the weekend up in Ukiah, where Rev. Jones had gathered his congregation, before he moved the Temple to its San Francisco location. Because I looked at most religions as being hypocritical entities, I always found a way to turn down her request. But I must admit, she was wearing me down with her admirations of this preacher and his church, and I was tempted to at least go up one weekend and check it out. The final inspiration to center this play on a family that would be arriving in Jonestown the week before the tragedy was learning that my friend and her foster family was almost the real-life counterpart to the fictional Brown family: they missed their flight to Guyana because of airline technicalities. Had my friends gone, they surely would have died.

In creating this drama, I thought it would be interesting if it became focused on the one member of the family who did not want to go, the father fighting to keep his whole family intact and near. The basic premise of Bloodlines to Oblivion then, is, can a husband’s love convince a wife that, in deciding between him and Jim Jones, she needed to choose him. If the husband lost, his whole “bloodline” and family would be wiped out.

I knew that I wanted to have the audience rooting for love over religion. While staged as a typical family drama, the consequences represented so much more. The audience knew what would happen to these characters caught up in the whirlwind of religion. I was able to break the family down. I had everyone, from the drugged-out son to the prodigal pregnant daughter, to the excited young son ready for the adventure, to the mother who only wanted to escape the racism of America for a better future for her children. The steady presence was the no-nonsense father who had read all the early signs of the evil of this preacher and his church.

Most writers will revisit a script after 35 years, because they have grown into artistic maturity and feel they can always make a script much better than it was when they were new to writing. I must say that even after this time, I would not change anything with the play. I think it stands on its own, and most people who have read it understand its power. I will admit that the depiction of my characters was not centered on any research I did for the type of folks who were members of the church. My characters were folks that I observed in my community. I also feel that, even with the films and documentaries on Jonestown, my play holds up well mainly because I centered in on a family. I never questioned the mother’s fervent belief in Rev. Jones, even though I was aware of real life criticism by disgruntled former members.

The proudest achievement I had is that many people who came to see my play told me that I had been fair and accurate in my portrayal of these family members. I have to know the sensibilities of my subject matter in all my plays, and Bloodlines to Oblivion was a perfect example. Just as I have become a writer who writes fiction based on real life events and characters, I have always been very careful of how I paint these characters and never ever slander or defame them. Sometimes I walk up to the line of controversy, but the metric to which my depiction can go is: what if someone is in my audience who may be offended about how I might portray someone they loved, knew, or associated with. I hope to demonstrate that respect, even for those who don’t deserve it.

(A novelist, short story writer, playwright and screenwriter, Jamal Williams has a Master of Creative Writing from The University of San Francisco State at San Francisco. In his multi-generation career he had at least 30 of his plays in productions. Taking control of his legacy, he has published fifteen books of his plays in print and completed a two-book set of Sci-fi/Horror entitled Where Dark Things Hide available on Barnes & Noble and Amazon Books. He can be reached at jammit50@gmail.com.)