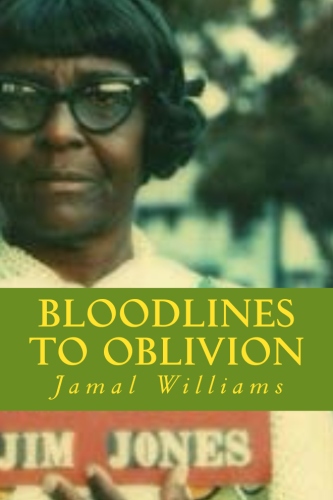

Bloodlines to Oblivion. By Jamal Williams. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, August 2017. 125 pages. $12.00 paper.

Bloodlines to Oblivion. By Jamal Williams. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, August 2017. 125 pages. $12.00 paper.

Jamal Williams’ play, Bloodlines to Oblivion, is an opportunity missed. Set against the racially-turbulent backdrop of San Francisco in the late 1970’s, it explores how members of one family can have wildly divergent views on the meaning of liberty, loyalty, and salvation. It is not, however, a play about Jonestown.

Bloodlines to Oblivion belongs to the dramatic genre of domestic tragedy: the momentum of the story is driven by a set of inevitable circumstances by which the protagonist or other main characters come to ruin. In Bloodlines to Oblivion, these circumstances revolve around Hazel Brown, the matriarch of her family, who is preparing to move to the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project in Guyana, against the wishes of her husband Arthur.

Hazel also intends on taking their 17-year-old daughter Angel along with her, though Angel is secretly opposed to the move. Although interested in the inclusive message of salvation offered by Reverend Jim Jones, Angel has recently discovered she is pregnant by her boyfriend, a fact she had kept secret from her mother, since similar circumstances resulted in a protracted estrangement between Hazel and Angel’s older sister Blue. Hazel’s son, Junior, is a 20-something junkie whose drug habit has landed him in hot water; he has 48 hours to come up with the money he owes his dealer or he will be killed – a convenient plot twist that results in Junior planning to join his mother in Guyana.

The main tension in the plot arises from Hazel’s unbending desire to move to Jonestown and her husband’s refusal to join her. Arthur employs various tactics to thwart Hazel’s plans, but none of them are successful. The play ends with Arthur alone, his wife and three children on a plane to Guyana.

A major flaw in Bloodlines to Oblivion is that the sense of impending doom—the tragic momentum of the story—is not provided by the characters, the plot, the dialogue, or even the playwright. The sense of a foreclosed defeat is provided wholly by the audience in the form of dramatic irony. (Dramatic irony describes when the audience is aware of something the characters in the story are not aware of – in this case, how things turn out for nearly all those who moved to Jonestown.) Because the action in the play concludes without explicitly referencing the mass suicide, the playwright is relying on the audience having knowledge of what awaits Hazel and her children in the jungle. It is then up to the audience to bring that to imbue the dramatic action with a sense of tragedy. While it is likely that most people who read or see Bloodlines to Oblivion would have that knowledge, it should not be incumbent on an audience to create such momentum in order for it work as a piece of theatre.

A second by-product of this dramatic irony – of this reliance on the audience knowledge – is that nothing that occurs on the page or stage is surprising. And absent any element of surprise, the play is simply not compelling. The characters are largely two-dimensional, and the dialogue, while nicely constructed from an authentic sounding black vernacular of the late seventies, is fairly simplistic. This results in a bizarre situation wherein the events of the story are simultaneously horrific and uninteresting.

There were other options for creating dramatic tension that Williams could have – but did not – employ. Rather than using Jonestown as a device or vehicle for creating dramatic irony, he could have treated the settlement in Guyana as a character, allowing its influence and mystery to permeate and saturate the Brown family residence and color their relationships to one another. The Aran Islands by J.M. Synge, is an excellent example of how something inanimate – a remote and unforgiving seascape that swallows fishermen, mercilessly creating orphans and widows – can be a fully-developed character, creating a tragic momentum without the audience having to bring dramatic irony to bear.

Another option would have been to weave the tragic events of Jonestown into the narrative by way of time shifts or flashbacks. This would have allowed an exploration of things truly tragic: how those who lost loved ones at Jonestown dealt with the grief of not getting to say goodbye, separated from their family members – whether those family members were by birth or choice – when the end came. Or the sense, felt by some who desperately wanted to go, but who didn’t – for whatever reason – of being left behind and then having to deal with the aftermath.

Finally, there were typos and mislabeling of dialogue in the script, which is odd for a play originally written 30 years ago. It may seem nitpicky to mention proofreading errors, but their presence leaves the reader with the feeling that he is looking at a first draft. It contributes to a nagging sense, given some of the shortcomings addressed above, that the playwright did not allow the play to fully develop before committing it to paper.

There is a positive note to mention. Bloodlines to Oblivion is rooted in a part of the Jonestown story that may not be clear to some outsiders: that nearly all of those who moved to Guyana did so of their own accord, willingly and joyfully. While some sought escape, and others sought paradise, all sought community and a sense of family that they may not have felt elsewhere. Clearly that is what Jamal Williams was trying to portray with his fictionalized Brown family. Unfortunately, the execution does not live up to the premise.

(Aaron R. Duggan is an independent scholar who did his undergraduate work at San Diego State University where he graduated magna cum laude as an Interdisciplinary Studies major with an emphasis in Theatre Arts, Sociology, and Religious Studies. He subsequently earned his M.A. and Ph.D. in Mythological Studies from Pacifica Graduate Institute. He resides in La Mesa, California with his ever-supportive wife Beth, their cat Bacon and their two chickens, Kate and Bianca.)