The Road So Far

It’s good to laugh at yourself now and then. It’s been nine years (!) since I first wrote here of my idea to center an opera around Christine Miller’s brave attempt to turn the tide of Nov. 18, 1978. I followed up the original piece with articles in 2012 and 2015. I’ll say this: I’m extremely excited and happy with the work that’s come out, but it has come out slowly, competing as it does with three jobs and six choirs.

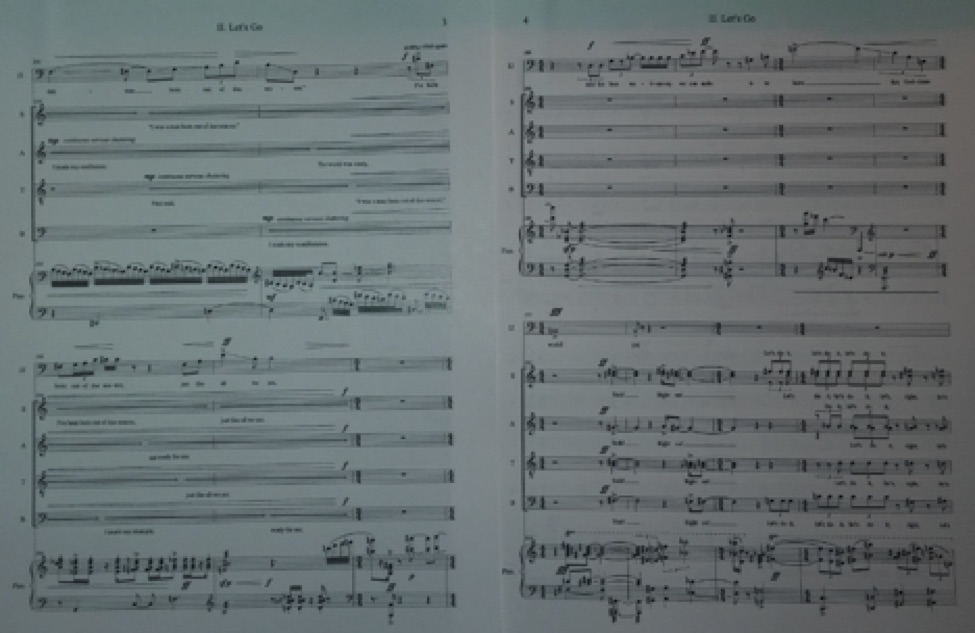

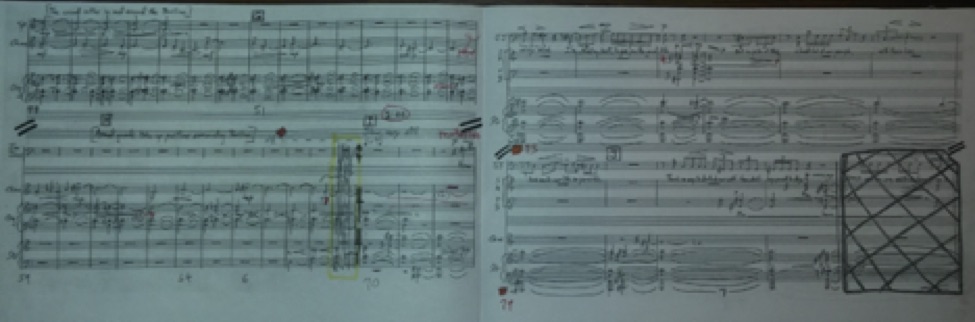

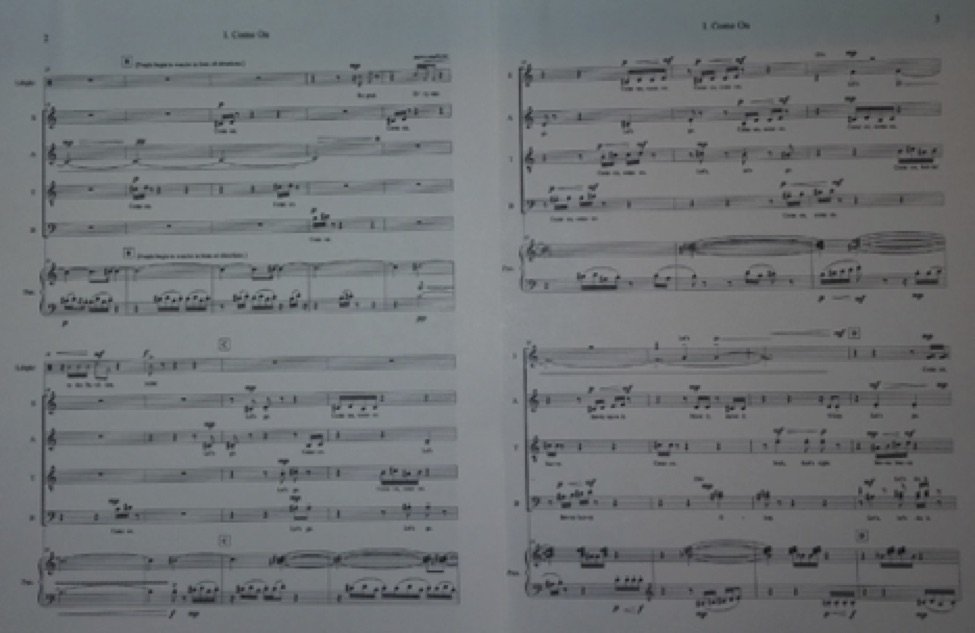

I have about 20 to 25 minutes of music now, in various states of semi-orchestration or piano reduction. A bit of it is engraved; most of it is still by hand. But progress is accelerating. I recently managed to free up more composing time in my weekly schedule, so that helps. In any event, making this piece requires becoming intimate with the subject matter, so it’s probably good to take breaks now and then.

Looking over what I wrote three years ago, I also laughed at my statement that “as of a few weeks ago, that scene is completed, save for a few cosmetic scoring details.”Well. Here’s the deal. Nine years ago I started writing, literally at a random spot in the middle of Christine and Jim’s dialogue. I couldn’t imagine yet how this scene might begin or develop. I just thought I’d set a few lines to get a feel for it, then jump to an aria for Christine.

Once I began, though, there was no turning back. What I’m now calling the Dialogue Scene began to take on a shape and trajectory, and eventually did lead to an aria, one that grew into three or four times the scope I’d originally imagined. Christine’s aria is now a central turning point of the entire opera, the moment when she almost has them in the palm of her hand, in this telling anyway. I also wrote three years ago about the aria’s aftermath, when Jim’s loyalists pile on to denounce her, when Jim re-takes control of the conversation, and as the crowd roars its approval. The scene ends there, leading to a final scene which will deal with the deaths and what we might learn from the tragedy today.

But wait. I may have finished the Dialogue Scene, but I never began it! The short-term goal was to perform this much, to see what I had, and to use the resultant recording to secure a full commission. But what I realized was I had to write the beginning of it and then join it up to the second half. Then I’d have a complete scene, even if it does last 40 minutes. I decided, let’s do this the right way.

So I thought, given that the scene ends with the crowd exulting, “Come on, let’s do it, we’re all ready to go, let’s go,” how should it begin? What if, instead of starting with Jim’s first line of the Death Tape – “How very much I’ve tried my best to give you the good life” – it opens with the loudspeaker calling everyone to the Pavilion, and people leaving their cabins, speaking in normal tones and everyday conversation. “Come on,” they’d say to each other, “let’s go,” phrases that would take on drastically different meanings later. What did they think as they walked along the pathways that afternoon? Most of them had seen what happened an hour earlier, when the defectors left with the congressman, so they had to know something huge was brewing. But maybe some of them thought this would be just another meeting. “Come on. Let’s go.” After all, they’d had White Nights before, and nothing had really come of them.

To me, this was the perfect setup for what is about to happen. There is a mundane tone in the way they keep repeating those phrases, but underneath, a quiet tension in the pulsating piano tremors and long sustained string notes tells the audience, “Oh yeah, something’s definitely up.” Then, as they arrive and begin settling in, we hear strangely wistful organ chords and church bells tolling. Peoples Temple was – in the beginning, anyway – deeply rooted in the evangelical church, and echoes of that reverberate here in stark contrast to the sight of armed guards taking up positions as people arrive.

To me, this was the perfect setup for what is about to happen. There is a mundane tone in the way they keep repeating those phrases, but underneath, a quiet tension in the pulsating piano tremors and long sustained string notes tells the audience, “Oh yeah, something’s definitely up.” Then, as they arrive and begin settling in, we hear strangely wistful organ chords and church bells tolling. Peoples Temple was – in the beginning, anyway – deeply rooted in the evangelical church, and echoes of that reverberate here in stark contrast to the sight of armed guards taking up positions as people arrive.

And then, Jim begins. “How very much…”

This music all came fairly quickly. Now I’m most of the way through Jim’s opening speech, just before the dialogue with Christine begins. As I move through this, I realize that part of my job is to introduce and foreshadow musical motifs that will appear later in the scene (which are already written). Jim has a brassy “delusion of grandeur” theme crop up several times in the scene’s second half. Christine is usually associated with harp arpeggios and swelling viola chords. McElvane is always accompanied by Hammond organ riffs. There are a few other motifs as well. Now all of them must be introduced, and “grow into” what will happen later. It’s a weird way to proceed, but I think it’s working.

A necessary result of storytelling in this case is that many specific references made by Jim and others that day had to be removed. This includes people and ideas that were central to what led to this moment – Ujara, Tim Stoen, the Mertles, Richard Dwyer, the film I Will Fight No More Forever – and I hate to not include them, but given the pace of opera, they would become distracting subplots. The truth is, at least half of the transcript has to be shaved away to make a workable libretto, especially Jim’s long, wandering ramblings. Bit by bit, I’m finding the core issues of this opera, one of which is simply seeing the story through Christine’s eyes.

There are also the survivors. Earlier, I’d imagined the final scene depicting the deaths, followed by Christine and the other deceased meeting in the afterlife, or singing onstage after they died. The idea was to illustrate that she was right and he was wrong. Now, I think there’s a better way of doing it. I think this opera will have “bookends.” The very beginning will feature survivors in the present day, meeting as they do each November to honor their beloved friends and the dreams they had when they joined PT. This will segue into the PT backstory. Then at the end, the deaths will be depicted symbolically, not morbidly, even as simultaneously the survivors return to offer a present-day perspective. Anyone with the best intentions can be brought under the spell of a malevolent charlatan, they’ll say, if that charlatan has a powerful enough charisma to persuade you to surrender your free will by seeming to offer exactly what you need. If we know anything 40 years after Jonestown, it’s that these devils can take any shape, co-opting any political cause to their advantage, and if you aren’t vigilant, by the time you’re headed toward the edge, it’s too late to turn back.

Finally, Some Performances

There’s enough music now to perform a little of it, in stages. Coming this October 13, a new-music chorus I work with will premiere the brief crowd snippets that begin and end the Dialogue Scene. We’re talking about literally four minutes of music, with piano only, no orchestra yet, but rehearsals just began and I’m very excited about getting that much of it in front of real live people. The group, C4: The Choral Composer/Conductor Collective, is fantastic and already has their mitts around it.

At the same time, I’m applying for a grant that would fund a performance of the entire 35-40 minute Dialogue Scene, a little over a year from now. This performance would involve the lead characters and a few more instruments, as well as C4 again playing the crowd. The recording of that, then, provides the best shot at securing commissions for the full work, including several scenes not even begun yet, as well as the full orchestration.

This thing is happening slowly but surely. At times the pace is maddening, but something of this scale needs to evolve as it will. As frustrating as it can be at times, I need to get out of the way and let it. Hopefully, anyone who’s interested in hearing some of it won’t have to wait too much longer.

As always, I welcome any thoughts or feedback. I hope to reach out soon to people in this community to help me with some questions I still have, both about the compelling story and the strong characters that form the foundation of this work.

(Perry Townsend is a composer based in New York City. He can be reached at ptownsend@immerbox.com.)