Please allow me to introduce myself

I’m a man of wealth and taste

I’ve been around for a long, long year

stole many a man’s soul to waste…

Pleased to meet you hope you guessed my name,

but what’s puzzling you is the nature of my game[1]

Punctuated human tragedies compel critical reflection on both the outcomes and causal pathways for better understanding towards reconciliation and prevention. With the 40thanniversary of the Jonestown tragedy, the story of Peoples Temple and its leader, Jim Jones, demands the exploration of many perspectives. Most, if not all, of the literature surrounding the research and reflection on Peoples Temple and Jim Jones centers on the social phenomenon of religious cults or the study of individual and collective psychology to gain a better understanding for the motivations of the leaders and followers in such a horrific case. While this event was unprecedented in American history, it wasn’t the first instance of mass suicide in world history, not even the first example of an apocalyptic group led by a messianic figure committing suicide. Consider, for example, the Sicarii Jewish zealots who committed suicide under the leadership of Eleazar ben Ya’ir in 73AD after their mountain base at Masada was assailed by the Roman Army.

Examining the Jonestown tragedy in retrospect under a structured theoretical lens of international security studies allows us to prepare negotiators, strategists, and policy makers for future similar scenarios. While not particularly intuitive to the history of Peoples Temple, this primer proposes that Jim Jones was a type of violent non-state actor who utilized warlord means towards achieving a transcendental goal which led to an unimaginably tragic end. Further, the 1970s-era government of Guyana valued the utility of establishing Jonestown and therefore extended a level of legitimacy to Jim Jones to mitigate its continuous border dispute with neighboring Venezuela and within the context of hegemonic Cold War alignments of the time. Lastly, US inter-agency efforts were not synchronized in dealing with Jim Jones once he had people isolated in Jonestown, nor did the US government really understand Jones’ character type to mitigate potentials. This paper defines Jim Jones as a pariah warlord-type leader within a proposed typology theory, then puts this definition into structural context through the lens of utility and legitimacy within international security considerations.

* * * * *

Thinking of Jim Jones as using a warlord style of governance might seem utterly ridiculous to those unfamiliar with the defined array of violent non-state actors who exist within the American and European academy. The very word “warlord” conjures strong mental images of a hardened warrior on horseback, laden with bandoliers of ammunition, weapons, dressed in the non-uniform of a guerilla fighter, and with a loyal army in tote. In the context of the modern day, noted academic and author Dr. William Reno posits that “warlordism” is a rejection of conventional state systems when describing the type of governance it affords to the people within its control. He also makes note that warlordism is a “rational response” to lack of state capacity in an interconnected world.[2]

The term “warlord” has been studied in esteemed academic circles for years, bringing with it a broad horizon of definitions spanning both space and time. The warlord leader seeks to take advantage of economic, cultural, and political imbalances for personal gain.[3] There are instances when warlords serve a purpose, providing governance in the absence of state capacity, acting as a proxy towards a desired outcome, or supporting some underlying political need. Warlords can be helpful to a patron state, serve as an indicator of gaps in state capacity, and allow states to conserve vital national resources whilst in pursuit of a security interest. However, warlords and warlord-type leaders utilized as proxies towards desired ends come at great risk and costs as demonstrated by the outcomes in the Jonestown tragedy.

What is a warlord, and how does it relate to Jim Jones? The warlord (and warlord-type leader) is a self-interested, charismatic, violent non-state actor who exercises sovereignty through coercive means, and who is sponsored by patrons for different levels of utility and legitimacy towards achieving transactional and/or transcendental goals. In my ongoing research, including extensive literature reviews on the subject, I have proposed the following typology of warlords: the social warlord, the free-ranging warlord, and the pariah warlord. This paper will use this typology to put the case of Jim Jones in proper context.

The distinction between the three warlord types are based on three variables: the warlord’s legitimacy (which is scalable) based on relationships with legitimate patron-actors within the international system of states, their relative utility to those patrons, and their personal motivations/goals. The type of warlord is relative to perspective and conditions, and warlord types can morph and shift over time as no human being is static. Generally, it is more probable for a social warlord to morph towards free-ranging and pariah types than the other way around; once a pariah, it usually means no going back towards social. The social warlord has the highest level of utility and value, developing strong relationships with a patron state for high levels of legitimacy and to create opportunity space towards transactional, self-interested goals. Secondly, the free-ranging warlord recognizes the utility of the international system of states and values external networks for patron support, but seeks to operate outside the relationship-fold of the system putting their legitimacy and utility at greater risk towards realizing transactional, self-interested goals in a relatively unfettered manner. Lastly, the pariah warlord enjoys no legitimacy and is of little utility to states or other legitimate actors, as the motivations are generally senseless and the goals are almost purely transcendental. Moreover, pariahs seem almost apocalyptic in their expressed goals, interests, and behaviors, leaving little room for state governments to bargain and generate opportunity spheres to leverage warlord behavior over time.

Distinguishing between the three types is difficult without a theory or model from which to examine, as one type can morph into another given the changing conditions of legitimacy, utility, and their motivations/goals; hence my proposed theoretical model.

Warlords are generally charismatic and self-interested, monopolize on the means of coercion and violence, are usually connected with a transnational network and/or legitimate patron-actor, and must exercise effective governance to maintain some level of sovereignty. The distinguishing factors between states and warlords are that warlord systems serve a person and do not enjoy a consensus of legitimacy from the international system of states.[4] The term “warlord” can be traced back to the era just after the dissolution of the Roman Empire, when feudalism and the military lords associated with fiefdoms served as a primary means of security at very local levels across the European landscape. Most of the emergent warlord leaders of the immediate post-Roman time had military backgrounds, thus allowing them to master and wield the means of violence, coercing peasants and aristocrats alike into cohesive communities. In the face of marauding tribes, such as the Hun, the social contract with a local warlord was necessary to protect the interests of communities at risk.[5] The term “warlord” became synonymous with anyone who exercised the means of coercion and violence for self-serving reasons to compel, influence, and protect the society they led.

Advance into the twentieth century, there are numerous cases within the international system where warlord governance became an acceptable social contract based on compelling geo-political, security, and economic conditions. Many scholars posit that warlords live in defiance of the state system due to self-interest; however, my research demonstrates that the relationship between the warlord and the international system is more interactive and complex for a variety of reasons.[6] For example, it is quite clear that while starting Peoples Temple in Indiana in the 1950s and 1960s, Jim Jones’ initial intent was not to coerce and isolate people into a utopian-style existence in remote northwestern Guyana. Over time as his charisma and ambitions grew, Jones developed into a self-serving leader with an intense desire for power plagued with paranoia. Moreover, Jones’ methods for controlling and influencing his congregation in coercive and inspirational ways towards a transcendental idea became its own unique and poisonous brand of Christianity, characteristic of warlord behavior and influence.

Renowned sociologist Max Weber posits that there are three bases for legitimate rule: traditional, charismatic, and legal (or juridical) authority.[7] As with Jim Jones, warlords typically exercise effective charismatic rule. Charismatic rule is the premise that legitimate authority stems from the talents and/or acts of an individual. Charismatic leaders have a certain unquantifiable trait that makes them unique and tend to have great influence over others. Jim Jones was clearly this type of charismatic personality. Charismatic rule differentiates a legitimate state actor from a warlord-type leader, as state systems draw their authorities from legal institutions. In the state system, the collective is governed by an impersonal structure that transcends one person. In a warlord’s domain, very often, authorities are based on demonstrated talent and charisma. The system is the warlord, and the warlord is the system. Once the warlord has expired from the position of leadership, then the system runs great risk for collapse and/or gradual decline. Out of the three types, the pariah warlord is more prone to see the futility of the system beyond themselves, and therefore, if feeling threatened (placed into a “check-mate” situation) are more prone towards designing an “end-game plan” for the system itself. In the case of Peoples Temple and Jonestown, it became apparent that multiple agencies within the United States government were closing in on Jim Jones for potential extradition from Guyana to face legal allegations ranging from tax evasion to kidnapping. This led to “end-game plans” being operationalized and the November 1978 mass suicides.

Warlords typically rule over what political economist Douglas North refers to as a natural or limited access state, where the means of violence is retained at the level of an elite class and used as leverage amongst domestic audiences for cooperation or compliance.[8] Therefore, the warlord exercises positive or empirical sovereignty over a particular domain, before legal or juridical sovereignty is declared and/or recognized, without regards to a state system, without legitimacy of state consensus, and in areas of limited statehood (often referred to as areas of negative sovereignty).[9] Quasi-legitimacy is determined through the relationships the warlord enjoys with certain states or legitimate entities. To facilitate this sovereignty and legitimacy, Jim Jones had to seek a unique set of circumstances within a weaker state in which Peoples Temple could thrive with an acceptable level of utility. Even as his power grew stateside in San Francisco, Jones needed to seek a more isolated, less regulated, and more complimentary set of socio-economic/political conditions for Peoples Temple. The place where the three distinguishing characteristics of warlord types (motivations and goals, utility, and legitimacy) could come together towards a successful outcome was Jonestown.

First amongst the distinguishing traits of warlords in a typology are the goals and motivations. Jones’ goals were clearly transcendental based on a utopian-style Christian communal system. From the beginning, the concept of egalitarianism transcending ethnicity and citizenship were central to his philosophy as the leader of Peoples Temple. This philosophy was progressive for a religious organization in the United States in the 1960s and early 1970s. While overtly this philosophy was inclusive and sought to afford opportunities to those who were socially disenfranchised, it was also a very effective method to build intense loyalty and power based on strong human bonds between leader and congregation. Jones could be credited as a social savior of sorts, a person whom many people felt drawn to for having lifted them out of unfortunate situations. His charisma facilitated this philosophy with such undeniable passion that somewhere in the process, he was able to influence members of Peoples Temple to behave in unimaginable ways. For instance, there are many accounts of sexual predation on the part of Jones towards married women in the congregation which fomented both extreme division amongst families while solidifying loyalty and inseparable bonds with him personally. Jones further created inseparable bonds by siring children with married women which led to extreme feelings of betrayal on the part of husbands. Over time, these betrayals led to litigation proceedings against Jones, serving as a catalyst to modify his personal behaviors fomenting both paranoia and a desire for geographic isolation.

As Peoples Temple grew in downtown San Francisco in the early 1970s, so did the demand for capital. Capital generation became a primary effort for Peoples Temple and its leaders to increase their power and influence within the city. Evading both state and federal tax laws was practiced, clouding the transparency of the multiple business ventures by the church. Moreover, the Christian philosophy of Peoples Temple changed over time from altruism in preaching the word of God and saving people in unfortunate circumstances, to Jones openly deriding the word of God, putting himself front and center as the unquestionable leader of a humanist movement. Between the adulterous affairs resulting in extramarital children within the congregation, the betrayal and break-up of family units as a result, the litigation associated with the betrayals, and growing sums of capital from questionable business endeavors, Jones’ motivations and goals morphed over time from serving people to self-preservation. Eventually, the confluence of his Christian communal ideology and his desire towards self-preservation led to the establishment of the isolated community of Jonestown.

The second distinguishing characteristic is utility. It has already been explained that warlords live in spaces where there is limited state capacity. It has also been posited that charisma, self-interest, an effective means to govern, and therefore exercise of sovereignty over a domain, are common and necessary sets of traits for a warlord to exist. Utility is measured on a scale as is legitimacy, and it can be argued that levels of legitimacy determine the levels of utility and vice-versa. Cooley and Spruyt’s “Incomplete Contracting Theory” provides some level of explanation for the utility of a warlord, where a state outsources a portion of its sovereignty to a proxy in areas of limited statehood (also knowns as areas of negative sovereignty). Further, Thomas Risse’s “Private Public Partnership” theory provides some explanatory power in examining the utility of a warlord in time and space.[11] The “Private Public Partnership” theory addresses the emergent competition which occurs in areas of negative sovereignty and accounts for the involuntary nature of the social contract with human activity areas of high need and/or demand. With the theories of both the “Incomplete Contracting Theory” and the “Private Public Partnership,” we now have a theoretically adequate base of explanatory power for examining the utility of Jim Jones’ Jonestown project to the government of Guyana.

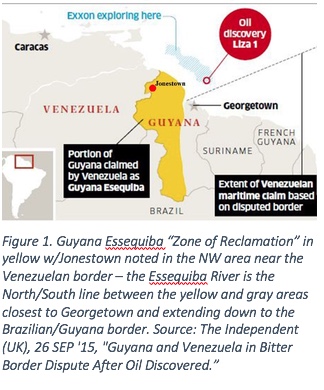

Jim Jones’ utility can be explained by understanding the geo-political and security situation in Guyana in the 1970s, which was managing two critical dilemmas: border security and internal political division tied to Cold War philosophies. The enduring border dispute with Venezuela over the lands west of the Essequibo River dated back as far as the early- to mid-19th century. In more recent times, after Guyana received its independence in 1966, the claims and controversies over this area, commonly referred to by the government of Venezuela as “Zona en Reclamación” or “Zone of Reclamation,” were revived on the international scene resulting in a treaty between the two countries. Jonestown was situated deep in the disputed zone and halfway between the competing capitals of Georgetown, Guyana and Caracas, Venezuela (see Figure 1).

Jim Jones’ utility can be explained by understanding the geo-political and security situation in Guyana in the 1970s, which was managing two critical dilemmas: border security and internal political division tied to Cold War philosophies. The enduring border dispute with Venezuela over the lands west of the Essequibo River dated back as far as the early- to mid-19th century. In more recent times, after Guyana received its independence in 1966, the claims and controversies over this area, commonly referred to by the government of Venezuela as “Zona en Reclamación” or “Zone of Reclamation,” were revived on the international scene resulting in a treaty between the two countries. Jonestown was situated deep in the disputed zone and halfway between the competing capitals of Georgetown, Guyana and Caracas, Venezuela (see Figure 1).

The significance of this area, particularly as it extends out into the Caribbean Sea, are primarily economic and political. The areas west of the Essequibo have both numerous agricultural uses and, of late, potential oil prospects off-shore. The government of Guyana under Prime Minister Forbes Burnham did not have a large capacity to dissuade Caracas from intervening in the region west of the Essequibo River. By agreeing to the establishment of Jonestown, a colony of US citizens in the disputed territory, it can be argued that Burnham forced Venezuela to be more cautious and strategic in its decision processes. In turn for Jim Jones and Peoples Temple, this meant leverage and space with the government of Guyana because of the purpose being fulfilled through giving strategic advantage to Georgetown. In that sense, Jonestown was almost a “free” agent carrying out the interests of the Guyanese government through a “Private-Public Partnership” to overcome an “incomplete contract.” This level of utility extended a certain level of credibility to the establishment of Jonestown by generating somewhat of a deterrent effect towards Caracas, but also guaranteeing US equities were at stake because of the presence of US citizens in a highly contested zone.

The third distinguishing characteristic is legitimacy. Columbia University’s Dr. Kimberly Marten argues that every warlord requires an external patron which lends legitimacy.[12] While this might seem a common characteristic amongst all warlords (and Dr. Marten quite clearly would argue it is), the level of patronage determines the level of legitimacy that a warlord enjoys. Since Guyana’s 1966 independence and formation as a Republic in 1970, the United States was heavily involved in domestic activities to dissuade pro-Communist movements from emerging within the political sphere. Concerns over emergent socialist and Communist movements in Latin America stemmed back to the Eisenhower Presidency, where the activities of agencies such as the Central Intelligence Agency sought to undermine leftist leaning governments by proxy to curb the demand for large sums of resources. Specific to Guyana, the United States was concerned about the emergence of two political leaders, Forbes Burnham of the mostly Afro-Guyanese Peoples National Congress (PNC) and Cheddi Jagan of the mostly Indo-Guyanese Peoples Progressive Party (PPP). Both parties were leftist, which complimented the Christian Communist philosophy of Jim Jones and Peoples Temple. Of note, the ruling PNC under Burnham in the mid-1970s declared itself a cooperative government internationally despite its ties to Cuba and greater pan-global Communist political movements. The decision to accept Peoples Temple’s proposal to establish Jonestown was a realpolitik move on the part of the Guyanese government to both assuage the United States of its hegemonic alignment concerns by establishing a US enclave (Jonestown), while at the same time ensuring a deterrent measure with the government of Venezuela by geo-positioning this US enclave well within a politically-contested territory. It is obvious that whatever risks the Guyanese government assessed with the establishment of Jonestown, their desire towards a positive relationship with the United States and establishing some US equities within their country was more important.

* * * * *

In summary, Jim Jones, as a pariah warlord type leader, embodied the paradox which led to a struggle between idealistic morality and primordial instincts. He took advantage of economic, cultural, and political imbalances, for personal gain in both San Francisco and in Guyana.[13] His intelligence and charisma enabled him to influence people through hope and opportunities, but at great cost and ultimately to serve his own selfish and delusional ends. Like all humans, Jones was not a static being, but a product of his experiences, the conditions around him, and the consequences of decisions made. Over time, his motivations went from altruistic to self-serving, and his goals went from community outreach to retreating into an isolationist state. While Jones might have started off a social or even free-ranging warlord-type leader when first negotiating with the government of Guyana to establish Jonestown in the early 1970s, external conditions with US government agencies and the mounting legal pressures he faced accelerated his motivations through the range of warlord-type behaviors towards being a pariah. If properly understood, a more coordinated US interagency approach in dealing with Jones once he retreated into Jonestown might have curbed his motivations and decisions to render a more acceptable outcome. Allegations and charges of kidnapping, tax evasion, and subversive activities, combined with the visit of Representative Leo Ryan at the request of worried families signaled to Jones that it was only a matter of time before the US government would work with the government of Guyana for extradition. Such dynamic and compelling conditions in Jones’ external relations with the US government led to a change in motivations more in line with pariah behavior, leading to a decision of executing the fatal “end-game” plan.

Jonestown served a utilitarian purpose, a “private-public partnership” for the Guyanese government in the absence of capacity and supporting the underlying political need towards dilemmas. Both domestically and regionally, Jim Jones earned the tacit legitimacy of the Guyanese government, as Jonestown served to ensure US equities were at stake for the national security interests of Guyana. However, due to shifting conditions in which Jones felt personally vulnerable and threatened, his goals and motivations changed, leading to him to choose a fatal set of decisions which tragically affected the lives of many innocent families.

Was the Jonestown massacre predictable? Could it have been prevented if US agencies had done their homework on Jim Jones? The answers are debatable in retrospect, but we can better learn from the tragedy that was Jonestown for future use.One of many lessons from Jonestown and Jim Jones is that these types of violent non-state actors must be studied, discussed, and disentangled to ensure the security of our citizens and national interests. In understanding the types of warlords, potential uses, and the high risks associated – as in the case of Jim Jones and the Jonestown massacre – US negotiators and policy makers can better develop well-informed options that are adaptive to the complex and dynamic developing regions of the world while being somewhat predictive in nature.

Works Cited

Ahram, Ariel I., and Charles King. 2012. “The Warlord as Arbitrageur.” Theory and Society 41 (2):169-186. doi: 10.1007/s11186-011-9162-4.

Brozus, Lars. 2011. “Applying the Governance Concept to Areas of Limited Statehood: Implications for International Foreign and Security Policy.” In Governance Without a State? Policies and Politics in Areas of Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse. New York City: Columbia University Press.

Fritz, Gordon H. McCormick and Lindsay. 2009. “The Logic of Warlord Politics.” Third World Quarterly 30 (1):81-112. doi: 10.1080/01436590802622391.

Gibbon, Edward. 1960. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. New York NY: Harcourt, Brace, and Company.

MacKinlay, John. 2000. “Defining Warlords.” International Peacekeeping 7 (1):48-62. doi: 10.1080/13533310008413818.

Marten, Kimberly. 2012. Warlords: Strong-Arm Brokers in Weak States. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press.

North, Douglass C., John Joseph Wallis, and Barry R. Weingast. 2009. Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Reno, William. 1998. Warlord Politics and African States. London UK: Lynne Reinner Publishers.

Risse, Thomas. 2011. “Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood.” In Governance Without a State? Policies and Politics in Areas of Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse. New York City: Columbia University Press.

Spruyt, Alexander Cooley and Hendrik. 2009. Contracting States: Soveriegn Transfers in International Relations. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Weber, Max. 2015. “Politics as Vocation.” In Weber’s Rationalism and Modern Society, edited by Tony and Dagmar Waters. New York: McMillan.

Notes

[1] The Rolling Stones. 1969. “Sympathy for the Devil.” In Beggars Banquet. London England: Decca

[2] Reno, William. 1998. Warlord Politics and African States. London UK: Lynne Reinner Publishers, 28

[3] Ahram, Ariel I., and Charles King. 2012. “The Warlord as Arbitrageur.” Theory and Society, 41 (2):169-186. doi: 10.1007/s11186-011-9162-4, 174/176

[4] Personal observation from living & working in Somalia – A great example of this distinction is the case of Jubbaland centered on the Southern Somali coastal city of Kismayo. President Madobe, Jubbaland’s Warlord President, is effective in providing all of the means of governance with consistency and some level of justice, but the system serves him and he (along with the Jubbaland Government) are not formally legitimized by the international system of states.

[5] Gibbon, Edward. 1960. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. New York NY: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 891

[6] MacKinlay, John. 2000. “Defining Warlords.” International Peacekeeping 7 (1):48-62.

[7] Weber, Max. 2015. “Politics as Vocation.” In Weber’s Rationalism and Modern Society, edited by Tony and Dagmar Waters. New York: McMillan, 137-138

[8] North, Douglass C., John Joseph Wallis, and Barry R. Weingast. 2009. Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. New York: Cambridge University Press, 20

[9] Fritz, Gordon H. McCormick and Lindsay. 2009. “The Logic of Warlord Politics.” Third World Quarterly 30 (1): 84. Also, Brozus, Lars. 2011. “Applying the Governance Concept to Areas of Limited Statehood: Implications for International Foreign and Security Policy.” In Governance Without a State? Policies and Politics in Areas of Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse. New York City: Columbia University Press, 263.

[10] Spruyt, Alexander Cooley and Hendrik. 2009. Contracting States: Sovereign Transfers in International Relations. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1-10

[11] Risse, Thomas. 2011. “Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood.” In Governance Without a State? Policies and Politics in Areas of Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse. New York City: Columbia University Press, 20

[12] Marten, Kimberly. 2012. Warlords: Strong-Arm Brokers in Weak States. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 190/191

[13] Ahram & King (2012), 174/176

(John Scott Nelson may be reached at jsn4@ksu.edu.)