During the years of Peoples Temple’s existence, there were many different individuals who ended up caught in its orbit. There were those who were friends of Jim Jones and the Temple, and there were foes, but there were also people who were, for a variety of reasons, both supporters and enemies depending on the situation. Plenty of people and groups were willing to use the Temple membership for their own ends, such as Bay area politicians who appreciated how the Temple could turn out so many people to any protest that suited them and their campaigns. However, in the Temple’s later years, some individuals saw People Temple, and the struggles that it was going through, as a way to gain personal fortune and fame.

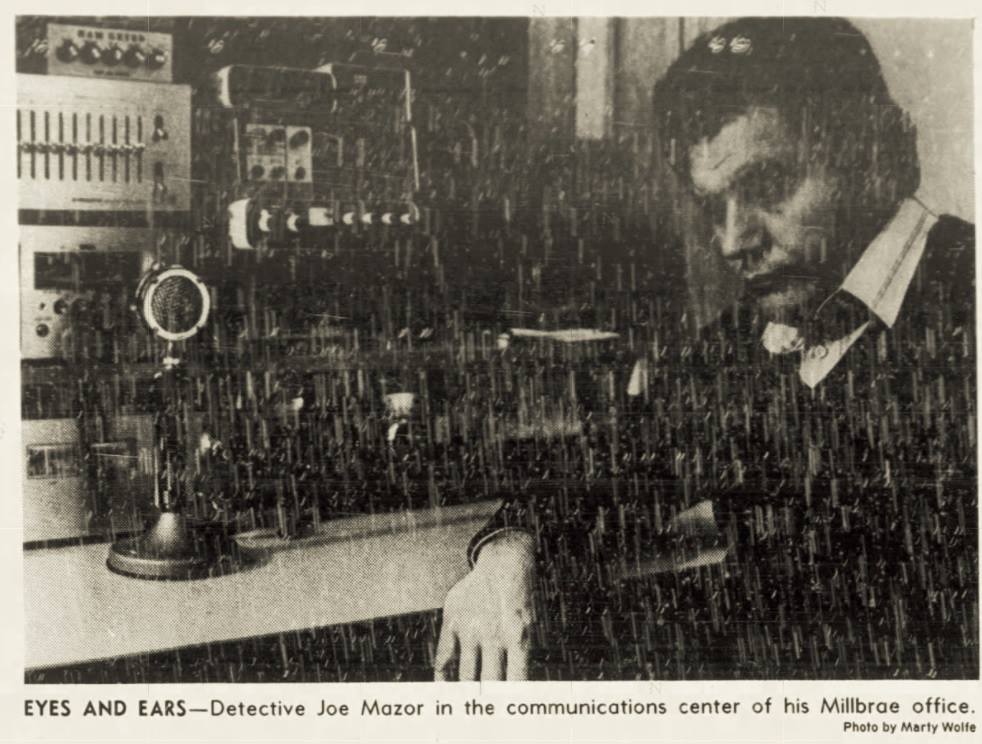

One such individual who saw Peoples Temple as an easy way to make money and a name for himself was Joe Mazor, a San Francisco private investigator.

One such individual who saw Peoples Temple as an easy way to make money and a name for himself was Joe Mazor, a San Francisco private investigator.

To say that Joe Mazor was a bizarre individual with a complicated personal background is an understatement of massive proportions. Mazor claimed that he had initially investigated Peoples Temple at the behest of a “friend in the San Francisco Police Department” in 1976 (Moore 238), but the veracity of that claim is unknown. What is known is that Mazor came to the attention of Peoples Temple and its leader, Jim Jones, in September 1977, near the end of the massive migration of Temple members to Jonestown. The exodus had begun in earnest in early August after Jones learned of an article scheduled for publication in New West Magazine. The article would quote former Temple members who claimed mistreatment and malfeasance at the hands of Jones and the leadership of Peoples Temple.

The sudden exodus left quite a few things unfinished. Many relatives of Temple members who left for Guyana were given no notice of the abrupt move. There were disagreements about property left behind, and, more significantly, about the families that were unceremoniously and irrevocably torn apart. For those people who had been debating which parent or other family member would have custody of a child, their legal situation had just become exponentially more complicated: the youngsters were suddenly in a foreign country, thousands of miles away.

Joe Mazor and His Work for the Concerned Relatives

Joe Mazor’s connection to Peoples Temple began through his association with the Concerned Relatives, an oppositional group to the Temple comprised of apostates and family members. As a private investigator, Mazor saw an opportunity to work with the Concerned Relatives in their efforts to bring their children and loved ones back from Guyana. Most of the means were legal, such as gaining custody through the California court system, although the idea of spiriting some of the children out of Jonestown itself was not dismissed. Mazor wanted his clients and the media to see him as a “good guy fighting Jim Jones to right some wrongs,” but he was only willing to do so for a fee. And he was reluctant to give any client a definitive quote for the price of his services.

As Mazor began his work for the Concerned Relatives, he notified San Francisco Examinerreporter Tim Reiterman, who was also investigating Jim Jones, Peoples Temple, and the circumstances of the sudden departure of so much of the membership to Guyana. Mazor invited Reiterman to meet with him to discuss what each man knew about the group and its leader. The reporter agreed, only to learn that Mazor had nothing new or groundbreaking to tell him. In his book Raven, Reiterman recalled that what Mazor really wanted to do was to make a proposal.

Mazor had a plan, an ambitious plan for an expedition to Guyana. Once there, he hoped to use U.S. court documents to wrest some eight children from the Temple on behalf of their parents or guardians. He was inviting the Examiner to cover the trip, if the Examiner paid for all expenses (Reiterman 353).

Neither Reiterman nor the Examiner wanted anything to do with Mazor, however. The idea sounded crazy and dangerous.

Jim Jones and Peoples Temple React to Joe Mazor

Meanwhile, Jim Jones and Peoples Temple had learned about Joe Mazor and what he was supposedly doing on behalf of the Concerned Relatives. In order to find out just what Mazor was telling those who would have him retrieve family members from Jonestown, the Temple had Carol McCoy, a trusted member, call Mazor. Posing as an apostate, McCoy said she was trying to get her children back from Jonestown, where she said they had been taken, without her consent, by her mother. Mazor replied that he felt she had a “seventy percent chance” of success. The best way to get her children back, he said, was by legal methods, such as establishing her custody of the children in a court of law and serving Jim Jones with legal papers at Jonestown.

McCoy’s report of the details of her meeting mirrored what the Concerned Relatives had learned: Mazor had refused to give her an exact quote of how much money she would need to spend in order to get her children back “legally,” but he had admitted that it would be “expensive.” Even worse, though, in the eyes of the Temple, Mazor claimed that he had already taken children out of Jonestown.

Suddenly, Jim Jones and the Temple leadership had a reason to be anxious about what Mazor was up to, and needed to gauge how much of a threat he really was to them. Peoples Temple began to dig into his background. They did a far more thorough job than he had done on them.

Peoples Temple was able to obtain a great deal of sensitive information on Joe Mazor and his past. One can see the fruits of their labor in the Temple’s own files which U.S. authorities collected from Jonestown after the deaths in November 1978, and which the FBI organized, reviewed, and eventually released pursuant to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, including one by the managers of this website. These files give researchers a deeper look into what was going on in Jonestown, including how the leadership of Jonestown regarded the outsiders that it encountered.

Peoples Temple was able to obtain a great deal of sensitive information on Joe Mazor and his past. One can see the fruits of their labor in the Temple’s own files which U.S. authorities collected from Jonestown after the deaths in November 1978, and which the FBI organized, reviewed, and eventually released pursuant to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, including one by the managers of this website. These files give researchers a deeper look into what was going on in Jonestown, including how the leadership of Jonestown regarded the outsiders that it encountered.

One of the most amazing things about the Temple’s own records on Joe Mazor – collected at RYMUR 89-4286-S-1 (hereafter S-1) – is what they tell us about the investigator’s checkered past. They also reveal much about the Temple itself, including how the Temple was able to obtain sensitive, perhaps even confidential, records on their would-be adversary. As an example, Peoples Temple had a copy of Joe Mazor’s official – and extensive – arrest and prison records. His rap sheet revealed that on June 25, 1965, Mazor had pleaded guilty to a felony fictitious check charge, as well as a felony bad check charge, and was sentenced to “a period of six months to fourteen years in prison” (S-1-71).

These records also indicate that Joe Mazor was a difficult inmate: he was never physically violent, but he was obstinate, both with guards and with prison medical staff. He claimed to have problems with his eyesight, but refused to let any of the medical staff examine him in anything other than a cursory way. In fact, he refused to allow prison doctors to have access to his previous test results regarding his “impaired vision.” The records also show that one prison guard gave a statement to the Department of Corrections that contradicted Mazor’s claim about his vision being “impaired.” The guard reported that he saw Mazor “reading a newspaper with only the aid of the colored glasses which he wears at all times” (S-1-80).

Through the California prison documents, the leadership of Peoples Temple also learned of the sordid details of Joe Mazor’s life following his release on parole in mid-February 1970. Hired on as a “Research Assistant” for a law firm – which the Temple thought was curious, considering his criminal history – Mazor wasn’t able to stay out of trouble for long. His parole was revoked on January 8, 1971 after he broke the conditions of his release in numerous ways, including incidents of writing fraudulent checks, drawing welfare assistance while being employed, and establishing lines of credit without the permission of his parole officer. In all, he was found to have five instances of violating his parole and was incarcerated once more (S-1, 59-70).

Other documents in the files show that Mazor’s infractions included thefts and cons which resulted in losses in excess of seven thousand dollars (S-1, 83-84). The California Adult Authority described Mazor as “an articulate person with a charming personality, who uses these assets to exploit those who help him” (S-1, 42-43). The same report refers to Mazor as “a smooth ‘con man’ with an insatiable desire to get ahead.”

Armed with this information, the Temple leadership was able to prepare itself for Mazor, and indeed, to formulate a plan that they thought would encourage Mazor to switch his loyalty from the Concerned Relatives to Jim Jones.

The Plan to Sway Joe Mazor

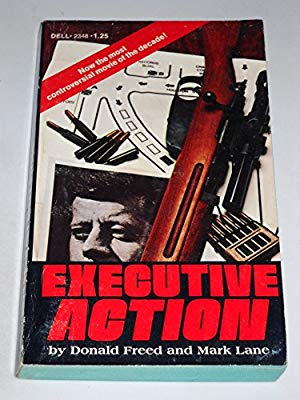

In spring 1978, Peoples Temple hired journalist and screenwriter Don Freed to conduct a PR campaign to improve the public’s perception of Jonestown and its leader. Freed was a writer with a history of spinning people and events in order to encourage others to see things in a different light. He was best known for his work on Executive Action, a 1973 movie which dramatized a conspiracy theory about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Freed agreed to the Temple’s proposal, and invited his friend, Mark Lane – a lawyer who had also participated in Executive Action– to work alongside him in giving Jonestown and its leader a more positive image. One of Freed’s tasks was to either neutralize Joe Mazor’s opposition to Peoples Temple, or – even better – to convince Mazor to abandon the Concerned Relatives and switch his allegiance to the Temple. To that end, a meeting was set up for the early afternoon of September 5, 1978, to which Freed, Lane, and Pat Richartz – an aide to Temple lawyer Charles Garry – invited Mazor to discuss his attempts to retrieve children from Jonestown. Following an informal lunch, Freed told Mazor that he was pursuing the possibility of a movie deal as part of his PR campaign. The movie would be a “showcase piece” for Jonestown, detailing the work of Peoples Temple in Guyana, and presenting it in a positive light. Freed said that director Paul Jarrico had already signed on to the picture, and that a script was being developed. According to Freed, Mazor would be “an ambiguous character” in the film. “For instance, it is conceivable that you could be a resource person for the film on a totally anonymous basis,” Freed said. “[Y]our part could exist as a person, an actor or yourself, could play that part. You could have credit and appear very much in front, you could appear in a press conference, etc. In other words, there is a range of possibilities” (S-1-366). In short, Freed was offering Mazor the chance to star in the film, or, at the very least, to receive payment – the amount of $25,000 was discussed – for acting as a consultant. Perhaps to sweeten the offer even more, Freed told the investigator that his “character” in the film would be written as a “hero.”

Freed agreed to the Temple’s proposal, and invited his friend, Mark Lane – a lawyer who had also participated in Executive Action– to work alongside him in giving Jonestown and its leader a more positive image. One of Freed’s tasks was to either neutralize Joe Mazor’s opposition to Peoples Temple, or – even better – to convince Mazor to abandon the Concerned Relatives and switch his allegiance to the Temple. To that end, a meeting was set up for the early afternoon of September 5, 1978, to which Freed, Lane, and Pat Richartz – an aide to Temple lawyer Charles Garry – invited Mazor to discuss his attempts to retrieve children from Jonestown. Following an informal lunch, Freed told Mazor that he was pursuing the possibility of a movie deal as part of his PR campaign. The movie would be a “showcase piece” for Jonestown, detailing the work of Peoples Temple in Guyana, and presenting it in a positive light. Freed said that director Paul Jarrico had already signed on to the picture, and that a script was being developed. According to Freed, Mazor would be “an ambiguous character” in the film. “For instance, it is conceivable that you could be a resource person for the film on a totally anonymous basis,” Freed said. “[Y]our part could exist as a person, an actor or yourself, could play that part. You could have credit and appear very much in front, you could appear in a press conference, etc. In other words, there is a range of possibilities” (S-1-366). In short, Freed was offering Mazor the chance to star in the film, or, at the very least, to receive payment – the amount of $25,000 was discussed – for acting as a consultant. Perhaps to sweeten the offer even more, Freed told the investigator that his “character” in the film would be written as a “hero.”

Even though there were plenty of opportunities to do so during the meeting, none of the other three people present questioned Mazor about why he was working against Jim Jones. Instead, Freed complimented him, saying at one point, “I can see that you’re sincere. This was your whole thing, to get the [children] back from these areas” (S-1-425). Whether or not Mazor was at any time sincere in his concern for the status of the children in Jonestown is highly dubious. As author Rebecca Moore writes in her book, A Sympathetic History of Jonestown, Mazor “saw Peoples Temple as a potential gold mine” (Moore 238). Mazor thought that Peoples Temple could be a bottomless resource for him, a way that he could earn a great deal of money, whichever side of the fence he worked. Any actual consideration for the individuals on either of the two sides, what they were going through, did not appear to be paramount in Joe Mazor’s mind.

Don Freed and Mark Lane employed another bit of strategy while attempting to sway Mazor: they decided to highlight the distaste for Tim Stoen that Mazor and Jim Jones shared. As Lane told Mazor, “you both have the same enemy, at least…. being Stoen” (S-1-388). In response, Mazor tried to argue that he had no issue with Stoen, but a few moments later, the investigator admitted that, while he was working for Grace Stoen in her custody battle, he had come to the conclusion that “Tim Stoen was always as dirty as Jones was” (S-1-391). Tim Reiterman also made note of this issue in Raven: “The ex-convict [Mazor] seemed to have a visceral hatred for the ex-prosecutor” (Reiterman 353). The exact reason that Joe Mazor saw Stoen so negatively is unknown.

At the end of the meeting, Mazor declined to commit to Freed’s offer. However, the idea of being a paid consultant on a movie about Jonestown – and the possibility of more consultant fees being paid to him – must have greatly intrigued Mazor, because suddenly, he was willing to travel to Jonestown and meet Jim Jones. He accepted a retainer of $2500 from Temple lawyer Charles Garry just before the two men left the United States to visit Jonestown.

Mazor Goes to Work For Jonestown and His “Enemy”

After the deaths at Jonestown, Mazor claimed that he had never even so much as considered working for Jim Jones or Peoples Temple. Mazor asserted that he had gone to visit Jonestown only out of a sense of curiosity. This completely contradicts his previous statements that he didn’t trust Jim Jones. Mazor also insisted in a January 21, 1979 article in The Los Angeles Timesthat he had rejected Freed’s offer, as well as one from Jim Jones himself during his visit to Jonestown, saying he “had too many unanswered questions about Jones’ operation” to even think about going forward (Maxwell).

The information in the S-1 file tells a different story.

By September 14, 1978, nine days after the meeting at the hotel with Freed, Lane and Richartz, Joe Mazor was speaking directly with the membership of Jonestown via HAM radio. Transcripts in S-1 document no fewer than four conversations that Mazor had that day with Eugene Chaikin, Sharon Amos, and Mike Prokes, and even with Jim Jones himself. Others who overheard these radio conversations included Harriet Tropp, Paula Adams and Teri Buford. Each person who communicated with Mazor, or listened in, was a member of Jonestown’s leadership core.

The main topic of conversation that day was Tim Stoen and his alleged theft of Peoples Temple money before he defected from the group. Mazor told Jones and his leadership that he believed that Tim Stoen stole “in excess of one million dollars” (S-1-14). The investigator further claimed that, while investigating Stoen on behalf of Peoples Temple, he had been able to track down bank accounts that Stoen had opened in London, England, as well as in the state of Colorado, near where Stoen’s parents lived. Mazor also discussed the possibility of Stoen having stashed some more money away in some Caribbean countries and/or secreted it away in his “various bank accounts.”

Upon hearing this news, Mike Prokes asked if Peoples Temple could hire Mazor for the specific purpose of investigating Tim Stoen. At first, Mazor said that he thought it could be done because there was “no conflict of interest” if he worked for the Temple. But by the end of the four conversations, Mazor had changed his mind and stated that he could not work for Peoples Temple until he finished some other “obligations.”

But once again, Mazor revealed his distaste for Tim Stoen during these HAM radio transmissions. Without revealing the basis for his belief, Mazor predicted that Stoen would likely commit suicide when Mazor’s information about him came to light. As if making light of a possible suicide wasn’t strange enough, Mazor was also oddly complimentary of Jim Jones. The comparison that Mazor had made of Stoen “being just as bad” as Jim Jones back during his hotel meeting with Don Freed was thrown to the wayside, as Mazor praised Jones and his group on multiple occasions. As Mazor told Eugene Chaikin, “Everyone seems to have found out who the bad guys are. You can tell Jim that I took off the black paint that I had painted on his hat, and it is now white” (S-1-28). While speaking to Jones directly in an earlier conversation, Mazor said, “Well, we [Peoples Temple and I] stopped fighting and started getting together. Loving is better than fighting” (S-1-19). These comments were obviously meant to make the Jonestown leadership group believe that Mazor had come around to their side, but the private investigator didn’t know how much caution the Temple used in interpreting what he told them.

The Way That Peoples Temple Viewed Joe Mazor

Following the HAM radio exchanges, Joe Mazor must have thought that Jones and the rest of Peoples Temple trusted him and his information about Stoen, and that he had persuaded them that his own intentions towards the group were sincere. But to the contrary, the individuals on the Jonestown radio were anything but convinced that Mazor was on their side. After all, they had already examined his records from his time in prison, and knew that his jailers had described him as a wannabe con man. They were all too aware of how Mazor was willing to betray his original clients when money was offered as an incentive. In Audiotape Q 268, Jones tells the Jonestown community that they need to find ways to ascertain just what Mazor knows when the investigator comes to visit the settlement. Anyone who might speak with the man during his visit should demand that he give them hard proof of any claims that he might make. Jones even goes so far as to say that if Mazor claims to know about CIA operatives being in Guyana for the purpose of keeping an eye on Jonestown, he “should be willing to give their names” to demonstrate his sincerity.

In what can only be described as a strange twist, Jones also states that he wants to find out exactly why Mazor has such intense hatred for Tim Stoen. It just didn’t seem to add up. After all, Mazor had once claimed that he didn’t have any animus towards Tim Stoen, and then suddenly, Mazor was “investigating” Stoen and making disparaging remarks about the ex-Temple member, seemingly for no reason.

Taken as a whole, there’s no doubt regarding whether Jim Jones trusted Joe Mazor: he did not.

The Purpose Behind Jim Jones Hiring Joe Mazor

But if that’s the case, why did Jim Jones hire Mazor to look into Tim Stoen and his alleged theft from Peoples Temple coffers? Such an act would seem counterintuitive. This author believes that Jones allowed Mazor to think that his information was considered valuable and trustworthy simply because the time that Mazor spent investigating Stoen would diminish and maybe even nullify any threat that Mazor himself might have posed to the Temple itself. If Mazor was busy looking at Stoen, he wouldn’t be busy doing any work on behalf of the Concerned Relatives. Moreover, Mazor certainly wasn’t about to hold any press conferences or participate in any sort of public protest about what was “going on in Jonestown,” if he was working for the Temple.

There was also another consequence of any deal Mazor might make with the Temple. Should the investigator decide to return to the Concerned Relatives in fighting Jim Jones, Peoples Temple could destroy Joe Mazor’s credibility, simply by letting the Concerned Relatives know that Mazor had accepted money from their antagonist. Mazor’s reputation would be wholly destroyed. Finally, perhaps in an act of serendipity, Mazor would completely lose out on the “gold mine” that he felt Peoples Temple represented. He would have nothing left that he could gain from either side of the dispute, and, even worse, his overall reputation as a private investigator would be deeply tarnished in the eyes of potential clients. Once Jones was able to persuade Mazor to work for him, Mazor’s future as an investigator would be dictated by Peoples Temple itself.

Joe Mazor After the Death of Peoples Temple

After the deaths in Jonestown on November 18, 1978, Joe Mazor found a way to extend his ability to cash in on his interactions with Peoples Temple. According to the previously-quoted article in the January 21, 1979 edition of The Los Angeles Times, Mazor “became a major source, though often unacknowledged, of information about the cult. He supplied tips and hard facts about finances, communications, virtually every aspect of Temple operations to television networks, local reporters and to the FBI” (Maxwell). Given his penchant for dramatic untruths, this is an alarming statement: just how many reporters paid Mazor for information about Peoples Temple, and how much of that information was as false or incomplete as Mazor’s other representations? No one will ever know.

Following the Jonestown tragedy, Joe Mazor disappeared from the spotlight until November 15, 1985, almost exactly seven years later. According to a short article in The San Francisco Chronicle, Mazor was involved that night in a domestic dispute with his wife. The argument ended when Nancy Lou Mazor shot Joe once in the chest. She called the police afterwards and, according to the article, told the dispatcher, “I just shot my husband. If you don’t get here in a hurry, I’ll do it again.”

Even the final moment of Joe Mazor’s life was immersed in controversy. Nancy Lou was arrested and booked for murder at the local jail, where she sat for a few days until her lawyer bailed her out. Her attorney was none other than Charles Garry, who had worked for Peoples Temple and who had been in Jonestown on its last day. Garry told the Chroniclethat he would employ a “self-defense claim” for his client. And there the story ended. There are no more public records of the disposition of the case.

The Vital Importance Of The S-1 FOIA Files In Research

So, what can the average researcher take away from the story of Joe Mazor’s life and his interactions with Peoples Temple? At first glance, the impression that one is left with is that they are unsolvable mysteries, that – at best – one can only form an opinion about whether Mazor tried to play both sides. There is no definitive explanation of the motives either of the private investigator or of the Temple in its consideration of its untrustworthy new ally. According to The Los Angeles Times, Mazor was adamant that he didn’t buy into what Jones told him, and he flat out denied having ever worked on behalf of the Temple in any capacity. This is where the true value of FOIA file S-1 comes into play. It gives the researcher an in-depth look into Mazor’s criminal past before he even heard of Peoples Temple or the Concerned Relatives. S-1 also clears up any question about whether or not he worked to investigate matters – in this case, the matter of Tim Stoen’s alleged theft of Temple funds – in exchange for payment from the Temple: as shown in the four HAM radio conversations Mazor had in September 1978, he most certainly did. The information in S-1 reveals quite clearly that Mazor was indeed a con man, or at the very least, an opportunist who was willing to say whatever people wanted to hear. if it meant that he would get paid.

Joe Mazor was out for himself only, and only for himself. In so doing, Mazor added to the paranoia and anxiety that existed in Jonestown, which in turn contributed to the deaths of 918 people on November 18, 1978. In listing the responsible parties for Jonestown’s final day, Joe Mazor has to be considered to be among them.

Final Comment Regarding Joe Mazor

The Los Angeles Timesarticle of January 21, 1979 includes Mazor’s lament that he had gotten to know Peoples Temple member Karen Layton in 1977. Karen, a member of the Jonestown inner circle, made periodic trips to Venezuela to purchase medical supplies for the settlement, in part because Jim Jones trusted her to return. Mazor used Karen Layton as an informant, and she apparently fed him a great deal of information. In October 1978, approximately three weeks after Mazor’s one known visit to Jonestown, Karen called him from a pay phone: things had taken a turn for the worse, she said, and she was frightened for her life. She wanted to try to use the cover of a supply run to Brazil that she was supposed to make to fly back to the U.S. instead. Despite his own alleged concerns about Jim Jones and the danger that he might represent, Mazor talked Karen into staying in the group, telling her that he needed her as a source of information. Mazor told The Los Angeles Timesthat once he heard that Representative Leo Ryan was heading for Jonestown, “I figured that somebody was going to get killed” (Maxwell).

Did Joe Mazor find a way to warn his informant that she needed to get out? Did he even make the effort? What is known is that Karen Layton was among those who died on November 18, 1978. And Mazor’s reaction, as reported in the Times? “She was a good kid… Damn, but this can be a rotten world.”

Work Cited

Alternative Consideration of Jonestown & Peoples Temple. Audiotape Q 268.

Maxwell, Evan. “Probe of Peoples Temple Hinted Horror Ahead.” The Los Angeles Times. January 21, 1979. Print.

Moore, Rebecca. A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in Peoples Temple. Lewiston, New York. The Edward Mellen Press. 1985.

Reiterman, Tim and John Jacobs. Raven: The Untold Story of Reverend Jim Jones and His People. New York. Dutton. 1982.

San Francisco Chronicle. “Detective Killed; Police Arrest Wife.” November 15, 1985. Print.

(Bonnie Yates is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. Her other contribution to this edition of the jonestown report is Representative of a Hero. Her previous articles may be found here. She may be reached here.)