(Editor’s note: This article is reprinted from Beyond the Veil: Reflexive Studies of Death and Dying (ed. Aubrey Thamann and Kalliopi M. Christodoulaki), New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2021, pp. 187-207. The pdf of the article is here.)

Whenever I have been asked why I study Peoples Temple, I have always been a bit embarrassed to say “for both personal and professional reasons.” I must first disclose my own connections to the mass murder-suicides at Jonestown and then explain how that led me into the field of religious studies. The fact that my two sisters and nephew died in Jonestown in 1978 inevitably leads some to say, with condescension, that my work must be very therapeutic. In addition, academics may question my objectivity, since I began from an apologetic stance before mastering the methodology and vocabulary of formal scholarship. My knowledge of Peoples Temple has grown over the past four decades since my family members died in Jonestown, so I have had to revise my initial thinking and admit in public forums and published monographs that I was wrong in my preliminary conclusions.

Thus, I find Renato Rosaldo’s critique of traditional forms of scholarship and academic writing—especially in the field of anthropology—extremely liberating.[1] His observation that “by invoking personal experience as an analytical category one risks easy dismissal” resonates strongly in my own career.[2] The expansion of the number of narratives depicting life in Peoples Temple resembles the “garage sale” metaphor Rosaldo utilizes to describe the transformation of classic forms of ethnography.[3] After Jonestown, the only opinions presented were those of critical ex-members; it took decades for other survivors, observers, and scholars to voice alternative views. Nevertheless, mainstream narratives of good and evil, leaders and followers, victims and victimizers took deep root, and were evident as recently as 2018, the year of the fortieth anniversary of the tragedy, despite the more nuanced perspectives that were available. Amongst the many competing narratives, one was literally set in stone to memorialize the Jonestown dead. Some background information is needed to set the stage for the drama that ensued to make this happen.

On 18 November 1978, more than 900 members of an agricultural commune died by ingesting cyanide-laced fruit punch. These deaths occurred shortly after a group of young men from the project assassinated Leo J. Ryan, a Member of Congress, and three journalists at a nearby jungle airstrip. Residents of Jonestown belonged to Peoples Temple, a new religious movement based in California that espoused racial equality and social justice. At least seventy percent of those who died were African American, with almost half of the total being African American women. With the exception of eight Guyanese children, all were U.S. citizens.

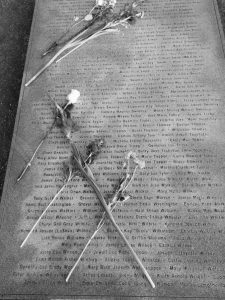

Because the deaths occurred on foreign soil, because the death toll was so high, and because the heat and humidity of the Guyana jungle was accelerating decomposition of the remains, the bodies were quickly repatriated to the United States without proper medico-legal investigation to determine how exactly they died. The dead were shipped to the military mortuary at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware, thousands of miles away from their homes in California. The unidentified and unclaimed bodies were kept in Dover for six months until an interfaith group in San Francisco found the financial means to transport and bury more than 400 bodies at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California. For decades, a simple granite marker identified the location. Meanwhile, the pastor of a nondenominational church in Los Angeles continuously raised money for a large memorial. Two seven-foot long engraved stone panels were unveiled at the thirtieth anniversary observance of the deaths, and more were planned to create a 36-foot wall, once the pastor secured additional funding. Efforts to erect a monument by a rival group, however, led to the successful installation in 2011 of four three-foot by six-foot granite plaques listing the names of all who died that day. Lawsuits followed, along with recriminations and criticism over the inclusion of the name of the group’s infamous leader, Jim Jones, on the plaques.

My husband, Fielding McGehee, and I played supporting roles throughout these controversies. Because we were not Temple members, but rather bereaved relatives, insiders “who were there” saw us as outsiders. My academic writing also pushed us into the etic category, as observers never entirely part of the group.[4] Our involvement in the memorialization process, however, drew us into the emic side, where we were clearly partisan.

Like Rosaldo, we had a unique social location by virtue of our suffering a loss and being able to write about a “grief observed.” The anthropologist’s examination of his own emotions upon the death of his wife helped him comprehend the rage felt by the Ilongot headhunters he had been studying and gain insight into what had once been incomprehensible. Rosaldo’s cool, scholarly, etic approach was transformed into a hot, emotional, emic perspective. He finally grasped what drove the bereaved Ilongot people of the Philippines to target a victim, behead him, and cast away the head—an act that freed them of the fury over their loss. This subjective experience gave Rosaldo unique insights that anyone might understand intellectually, but that only the bereaved can feel emotionally. I can relate on a private level to his experiences of the death of his wife and his brother, especially when he describes his parents’ emotions over the loss of their son. I did not fully understand my parents’ grief in 1978 until our own daughter died at age fifteen in 1995.

These experiences changed not only Rosaldo’s life but his outlook on the entire field of anthropology. While I value his insights, especially his critique of the historical emphasis on ritual rather than on emotion or bereavement—“force” is the word he frequently uses—I am also a bit leery of relying too much upon small subjective experiences for developing large theories concerning culture. Rosaldo himself notes this anxiety when he cautions against deriving a universal theory from somebody else’s personal knowledge.[5] Furthermore, an essentialist approach can emerge after harrowing events in which only direct participants are granted authority, credibility, or authenticity to speak. As the Argentine sociologist Elizabeth Jelin writes of traumatic incidents: “For many, personal suffering (especially when it was experienced directly in ‘your own body’ or by blood-connected relatives) can turn to be the basic determinant of legitimacy and truth.[6] Jelin warns that limiting authority to those who suffered directly may allow them to “slip into a monopolistic claim on the meaning and content of the memory and the truth.”[7]

A challenge to the monopoly of the personal-subjective—the essentialist stance—became visible in the clash over how the Jonestown dead were to be appropriately memorialized. The “community of the bereaved,” to use Rosaldo’s terminology,[8] did not agree on the question of who had the moral right to speak for the dead, and this lack of consensus played a large a role in the dispute. An unexpected twist made one faction more sympathetic to those who died than the other faction. The philosopher Avishai Margalit’s examination of the “thick” relations between family members helps to explain the behavior of the bereaved Jonestown community.

Utilizing the insights of Rosaldo, Margalit, and others, this chapter closely examines the process that led to the installation of a monument memorializing the Jonestown dead—a process that took 33 years. I begin by looking at the treatment of the bodies in what religion historian David Chidester calls “rituals of exclusion.”[9] It then discusses the processes that led to the decision to set a necrology—a list of the dead—in stone. While participants agreed to such a register in principle, tensions emerged over whose narrative would be told: were perpetrators to be listed with the innocents? Anger erupted between two rival groups that sought to erect a memorial, with hard feelings resulting once the four plaques were in place. Consideration of the relevant ethical issues follows, with a discussion of racial aspects involved in the controversy. This analysis makes it clear that incorporating personal insights into professional assessments of bereavement processes enriches our understanding of human culture—which is exactly Rosaldo’s point.

Rituals of Exclusion

Those who died in Jonestown fell far from home—geographically, socially, and politically. They had emigrated from the United States in the 1970s to the only South American country in which English was spoken, the Cooperative Republic of Guyana. They had abandoned friends, family, and belongings in the expectation that their utopian experiment would succeed. Those who arrived were predominantly African American, exiled from what they felt was a nation in which racism was hopelessly embedded within its very structure. They believed that communal sharing—what they called “apostolic socialism”—was the only way in which inequality might be overcome. Thus, when the utopia came to a shocking and gruesome end, the dead received little sympathy. Their remote location in the dense jungle interior of the Northwest District of Guyana made them relatively inaccessible. The corpses decayed rapidly in the intense heat and humidity.

Two medical doctors assigned by the U.S. government to report on the scene recommended that the bodies be buried on-site, given the state of advanced decomposition.[10] The Government of Guyana quickly quashed this suggestion, so members of the U.S. Army Graves Registration team were dispatched to recover the dead. This meant identifying the bodies before bagging them and shipping them, first via helicopter to Guyana’s capital city and then in large transport planes back to the United States. By the time their work ended, the team was using snow shovels to scoop up the liquified remains. The final figures for the dead were ultimately based on a literal head count, since skulls and other body parts often became detached from torsos.

The dreadful condition of the remains prompted what David Chidester called the “thingification” of the Jonestown dead—a survival mechanism for those who had to disinfect, prepare, and embalm the bodies before identification could be attempted back in the United States. Relying upon Mary Douglas’ important work on purity and danger,[11] Chidester noted three primary, overlapping fears that the people in Delaware had about potential contagion. The first anxiety concerned public health and the possibility that the physical bodies might contaminate the ground itself should they be buried in Delaware. The second apprehension centered on the possibility that Delaware might become a magnet for other cults, or even serve as a shrine to Jonestown. Finally, Chidester identified a worry over the spiritual vulnerability the living might have in the face of the evil dead. Thus, hygienic, social, and spiritual dangers threatened the purity of the people of Delaware.[12] “The Jonestown dead defied fundamental classifications regarding what it is to be a human being in American society,” Chidester concluded. “Therefore the bodies were not ‘ours’; they were not part of ‘us’; they were not to be included in the ritual recognition according to fully human dead in the American cult of the dead.”[13]

A first step toward remedying the situation was taken by outsiders. Comprised of Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish religious leaders in San Francisco, the Guyana Emergency Relief Committee (ERC) sought to bring the unclaimed and unidentified bodies back home. Because Peoples Temple had declared bankruptcy and went into receivership, the ERC had to acquire funding from the courts for this project. The easy part was getting money for transport and interment; the hard part was finding a cemetery that would accept the bodies. After several false starts with cemeteries in the San Francisco Bay Area, the ERC persuaded Evergreen Cemetery to inter the dead. Located in a predominantly middle class African American neighborhood in Oakland, California, Evergreen was, and remains today, an ideal final resting place. Hundreds of coffins were stacked on top of each other and placed in an excavated hillside with a magnificent view of San Francisco Bay.

Key to the ERC’s planning process was the rejection of cremation for disposition because it was inconsistent with black funerary traditions. Chidester compared the ERC’s actions to the rites of passage outlined by Arnold van Gennep.[14] The committee advocated a process by which the dead would be detached from the living through the transition of an earth burial, and would be reincorporated into the memory of a restored community.[15] In contrast, the city of Dover, Delaware reversed van Gennep’s formula by excluding the dead from the community, by refusing to bury the dead nearby, and rushing to remove the bodies from the state as quickly as possible.

As someone whose three-and-a-half year-old nephew is buried at Evergreen Cemetery, I cannot help but appreciate Rosaldo’s discussion of parody in anthropological discourse when I read Chidester’s account of rituals of exclusion and inclusion.[16] Chidester seems to exemplify Rosaldo’s point exactly about the classic focus on ritual at the expense of bereavement. Nevertheless, there is value in providing technical, rather than evocative, language to describe certain situations. To develop Chidester’s argument, I later wrote about how the exclusion of the stigmatized dead of Jonestown led to the disenfranchisement of grief suffered by those who personally knew them.[17] When bereaved relatives and Jonestown survivors read about disenfranchised grief, they suddenly had a vocabulary to describe exactly what they had experienced—or so they told me.

Chidester’s analysis misses the force felt by aggrieved relatives when they witnessed the disrespectful handling of the bodies. Like many other family members, I remain shocked over the failure of the U.S. government to properly investigate what actually happened in Jonestown.[18] The ignominious deaths, coupled with the unceremonious treatment of those who died, certainly ignited the desire to somehow restore their humanity through an appropriate memorial.

Memorial Mania

Erika Doss, a professor of American Studies, has identified a growing trend in modern society: the erection of temporary shrines and permanent memorials:

If wildly divergent in subject and style—few of today’s memorials hold to the classicizing sentiments of earlier generations—these commemorative sites collectively represent what I call “memorial mania”: the contemporary obsession with issues of memory and history and an urgent, excessive desire to express, or claim, those issues in visibly public contexts.[19]

A significant feature of many public monuments is the inclusion of names of the deceased—though the word “necrology” does not appear at all in her 2008 volume, and only a single time in a second book on the subject.[20] Yet “names are de rigueur” in American commemorative culture; they “are familiar, comforting, and recognizable signs of real people, literal evidence of humanity.”[21]

Relatives of the Jonestown dead needed this “literal evidence of humanity” of their loved ones. From the outset, the media dehumanized the dead by focusing on the bodies, in what religion historian Jonathan Z. Smith called the pornography of Jonestown: “The daily revisions of the body count, the details on the condition of the corpses . . . lurid details of beatings, sexual humiliation, and public acts of perversion.”[22] Few people apart from family and friends knew Peoples Temple members as human beings. Coupled with the removal of the bodies to Delaware, and the lack of identification of almost 400 individuals, the listing of names was a step toward restoring their humanity. Daniel Sherman observed that the names of the deceased stood for absent bodies—or for bodies without names—in the World War I memorials erected in France.[23] Such monuments transferred emotion usually directed toward the body, to the inscribed name, which symbolized concretely the body.[24] All of the proposals for a Jonestown monument included some sort of necrology in which, consciously or unconsciously, the names symbolized the unidentified and those interred elsewhere.

In the absence of personal grave markers, or even individual gravesites, for the Jonestown dead, the names became a paramount concern. In effect, they restored the humanity of the corpses, shown face-down in the mud again and again in the media. But, as Doss notes, naming becomes “a subject of considerable controversy as questions of who counts (victims and perpetrators?), who counts where and when . . . and who counts the most . . . are hashed out during the design process and even later.”[25] This turned out to be the case for the Jonestown monument.

A Tale of Two Monuments

Memorial services were held at San Francisco churches in 1979 to mark the first anniversary of the deaths. Los Angeles pastor, now bishop, Jynona Norwood began holding services each year at Evergreen Cemetery. Assisted by her uncle, Fred Lewis—whose wife and seven children died in Jonestown—Norwood was granted widespread legitimacy by virtue of the fact that she claimed twenty-seven relatives who died in the tragedy, including her mother. These annual services provided the opportunity for a variety of people to come together to remember the event: relatives, public officials, strangers. But less than a handful of survivors or former members of the Temple attended the annual observances. Many did not know of the service; some had become hostile to organized religion; and some remained too traumatized to participate.

Within a decade, Bishop Norwood began a fundraising campaign to erect a monument that would list the names of those who died. A committee comprised of Norwood, my father John V Moore, Jackie Speier (who was severely wounded in the attack on Congressman Ryan), Grace Stoen Jones (who fought Jim Jones over custody of her son), and others cooperated in the fundraising project. Although the committee raised several thousand dollars, it fell apart in 1985 over issues of control and authority.

Bishop Norwood clearly became what Elizabeth Jelin identifies as a “memory entrepreneur,” that is, an individual “who seek[s] social recognition and political legitimacy of one (their own) interpretation or narrative of the past.”[26] Norwood’s services, which had started out by honoring and remembering those who died, became political events, complete with endorsements and appearances by public officials. The victims were neglected, and the perpetrators—chiefly Jim Jones—were emphasized.

Meanwhile, survivors and former members began to “come out of the Peoples Temple closet,” in the words of one survivor, and started attending Bishop Norwood’s annual service. The twenty-fifth anniversary in 2003 seemed to mark a turning point. Many traveled from around the country and, in addition to attending Norwood’s morning event, they held a private remembrance ceremony in the afternoon, apart from the media. Although the private memorials grew in size, they never really rivaled the publicity-oriented morning services.

After three decades of continuous fundraising for a monument, Bishop Norwood unveiled two large monoliths on the thirtieth anniversary, with about one hundred names engraved on each. They were brought into the cemetery on sizeable trailers but were not installed. The 2008 service also precipitated the decision of most former Temple members to abandon Norwood’s service in favor of their own afternoon event. Her emphasis on the evil of Jim Jones had displaced the task of remembering the deceased.

Rival sets of memory entrepreneurs emerged as a result. It would be fair to say that my husband and I already functioned as such with our development of a website dedicated to gathering and publishing as much primary source information as possible about Peoples Temple and Jonestown.[27] Our goal then, and today, was to humanize the dead by remembering their lives and not only their deaths. Our entrepreneurial purpose had been, and remains, to preserve and present as many different narratives as possible. Yet, in a surprise to us, the most important element of the site became the listing of “Who Died?,” which features photographs, biographical information, and remembrances of each individual who died in Jonestown.[28] The popularity of this component demonstrated the ongoing desire for some type of memorialization, virtually if not concretely.

Another memory entrepreneur was Lela Howard, who established the Mary Pearl Willis Foundation in honor of her aunt who died in Jonestown. Howard offered a free service to relatives who wanted to locate the gravesites of other Jonestown victims. The subtext of her effort to identify the burial grounds of the dead was to restore dignity to African Americans. She was the first to successfully organize a public reading of all the names of those who died on 18 November 1978, including that of Jim Jones: this event did not occur until the thirtieth anniversary in 2008.

Anticult groups functioned as memory entrepreneurs as well. For example, the Cult Awareness Network used the deaths in Jonestown as a morality tale to warn the public against the danger of cults. Anticultists compared all new religious movements to Peoples Temple.[29]

In short, a number of memory entrepreneurs were engaged in employing “Jonestown” and all that the event signified for various purposes. Many of these and other entrepreneurs could claim equal or even superior moral authority to that of Bishop Norwood. These included residents of Jonestown who escaped the deaths merely by being elsewhere that day; individuals who lost members of their immediate family; and individuals who had been part of Peoples Temple.

An ad hoc group, the Jonestown Memorial Fund (JMF or Jonestown Memorial), eventually raised the money to complete the task of raising a monument. Comprised of Jim Jones Jr. (the adopted son of Jim Jones, who lost more than twenty relatives in Jonestown), John Cobb (who lost thirteen relatives), and Fielding McGehee, the committee met with officials at Evergreen Cemetery in the summer of 2010. They signed a contract with the cemetery later that year to deliver four plaques that would be set flat on the ground—rather than upright—to conform to the fragility of the hillside. Within three weeks, the JMF raised the $15,000 needed from more than one hundred twenty different donors. Evergreen Cemetery donated $25,000 worth of labor and materials to extensively restore the hillside and to outline the area with a circular stone wall topped by a wrought iron railing. A dedication service was held Memorial Day weekend, 29 May 2011. In less than a year, the JMF finished what Bishop Norwood had promised for more than thirty.

The three members of the JMF did not anticipate the furor that would ensue when they decided to include the name of Jim Jones among the 918 listed on the plaques. Because they saw the monument as denoting a historical event, they believed that it was imperative to name everyone who died that day.[30] Moreover, they felt that if they attempted to separate the innocent from the guilty, they would have to exclude any number of perpetrators: the killers of Congressman Ryan and the journalists; the medical staff who mixed and injected the poison; the Jonestown leadership group who planned the event; the parents who killed their children. According to this logic, only the murdered children were truly innocent and could be registered.

Ethics, Morality, and Memorialization

Common wisdom holds that morality tends to be personal, while ethics refers to collective notions of right and wrong. Yet Avishai Margalit finds ethics embedded in the “thick” relations between family members and tribal communities; morality, more general and more generic, is applied to universal situations, that is, occasions in which personal connections are “thin.” Morality, in his usage, “ought to guide our behavior toward those to whom we are related just by virtue of their being fellow human beings, and by virtue of no other attribute.”[31] Ethics, in contrast, is a form of caring that can be directed only at those “with whom we have historical relations, and not just a brief encounter.”[32]Thus, we have different obligations to human beings: “in morality, human respect; in ethics, caring and loyalty.”[33] How does this distinction work in the case of memorializing the Jonestown dead?

Emphasizing her personal losses, Jynona Norwood sought to prohibit the agents who caused the loss from being listed on any proposed monuments, finding them unworthy of remembrance. This would seem to fall within Margalit’s category of ethics, in which thick relations determine one’s actions. Although segregation between the worthy and the unworthy became clear in Bishop Norwood’s rhetoric over the years, it was strikingly evident at the fortieth anniversary celebration. At that time, she displayed three large (three-foot by eight-foot) plywood panels she called a “movable wall.” The names and photographs of selected deceased were mounted on these panels. Two panels bore the heading “Innocent Children,” and the third was labeled “Heroes Memorial.” (It was not clear why these adults were identified as heroes.) Before her service at Evergreen Cemetery begins each year, Bishop Norwood covers the memorial plaques that have been set into the ground with a green tarp so as to blot out Jim Jones’ name. Reiterating her claim that including Jones’ name is akin to listing Adolf Hitler on a Holocaust memorial, Bishop Norwood seems to place family and loyalty above any other consideration. Moreover, she continues to exhibit the anger and rage over the deaths that Rosaldo describes so vividly regarding his own wife’s demise.

Yet Bishop Norwood’s annual services rarely feature other relatives or survivors from Peoples Temple or Jonestown. Rather, they always showcase public officials as guest speakers. Printed programs publish testimonial letters from city, state, and national officials. The comedian Dick Gregory, for example, spoke at her service in 2010. The program from 2018 reprinted a Certificate of Honor from the mayor of San Francisco, a Certificate of Special Congressional Recognition from Congresswoman Barbara Lee, and a letter from Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi; Martin Luther King III was the keynote speaker. Despite the “thinness” of their association with the dead, this group explicitly chose sides, exhibiting the loyalty characteristic of Margalit’s ethical behavior.

The Jonestown Memorial services, on the other hand, are led by survivors and attract former Temple members, rather than the general public. As a result, this group functions, in effect, like a family. Although anyone can attend the informal services, few do. At the fortieth anniversary, for example, only a single Associated Press reporter was present in the afternoon; the TV trucks departed after Bishop Norwood’s morning service. Following the 18 November afternoon observance, all who attended were invited to gather at a no-host dinner at a nearby restaurant. On only two occasions has the survivor group printed a program: at the 2011 dedication of the plaques (in order to list all who died, and all who contributed to the cost of the plaques); and on the fortieth anniversary. Speakers at this last event had all been members of the Temple, with the exception of the children of survivors.

Perhaps most remarkable is the fact that the speakers at the afternoon service in 2018 represented different factions of Temple membership when it existed. Three had left the group in the early 1970s; one of these had been part of the “Eight Revolutionaries” who harshly criticized practices in the Temple.[34] Three had been on the Jonestown basketball team, who escaped the deaths by playing in Georgetown the weekend of the tragedy. Two others happened to be in the capital city as well. All undoubtedly would have died had they been in Jonestown on 18 November.

Ironically, those who support the inclusive necrology adopted Margalit’s “moral” stance of universalism, despite the thickness of their relationships and their widely different perspectives. While they do not necessarily approve of the inclusion of Jim Jones or others who can be considered perpetrators, they nevertheless embrace all of the dead by virtue of their shared humanity.

What seems paradoxical in these two approaches is that the ostensibly family-focused Norwood group represents official, non-relational interests, while the universalist group represents primarily former Temple members. It is the “universalists” who were primarily family members and the “exclusionists” who were primarily unrelated actors. This seems to be the opposite of what Margalit predicts.

The philosopher offers one possible explanation for this seeming anomaly: proximity. He examines the parable of the Good Samaritan in the New Testament (Luke 10:30–37) and observes that it is physical proximity, rather than friendship or association, that makes the wounded man on the road evoke compassion in the heart of his ethnic enemy, the Samaritan.[35] The Samaritan responded to a moral duty, but not an ethical one, which belonged to the injured man’s countrymen, who passed him by. “People who suffer close to us elicit more care and compassion than those who are remote.”[36] Similarly, the survivors of Jonestown knew many of the people whose names appeared on the plaques, whereas the officials at Bishop Norwood’s services did not. It seems as though those most intimately affected by the losses would bear the most hostility toward the perpetrators. The opposite was the case. The deceased had been real to them—had literally been neighbors and thus merited the compassion of being named. Although not all approved of including Jim Jones’ name on the plaques, they nevertheless could accept its appearance as part of the larger project of commemorating all who died on that date in history.

The Factor of Race

The majority of the Jonestown dead were African American. A two-day conference of black church leaders convened in 1979 saw the deaths as part of a long history of oppression and violence perpetrated by whites against blacks.[37] Scholarly works made African American involvement in the Temple a focal point of discussion.[38] Popular narratives of Jonestown, however, neglected or excluded distinctly black perspectives, even though two of the earliest accounts presented the eyewitness testimony of African Americans.[39] Several things happened to bring black consciousness to the forefront.

At the risk of appearing immodest, I believe that the Alternative Considerations website provided a venue for many different perspectives, including those of African Americans. In addition, the publication of demographic charts and graphs on the website revealed the devastating losses suffered by the black community in San Francisco.[40] The willingness of African American survivors to step forward and be interviewed in the media, especially in the twenty-first century, also reconfigured the Jonestown story.

One strand of the new narrative concentrated on victimization and exploitation. Although this had long been a constitutive part of Jonestown analyses—with members exploited for money, labor, sex, and more—adding the element of race dramatically altered the reception of this theme. Another strand highlighted the agency exhibited by African Americans in the Temple. Feminist author and memory entrepreneur Sikivu Hutchinson explicitly raised the issue of race when she asked, “Where are the black feminist readings on and scholarship about Peoples Temple and Jonestown?”[41]Her novel, White Nights, Black Paradise, addressed some of the issues involved in the erasure of African American women from the Jonestown story by presenting a diverse assortment of strong, black female characters.[42]

These and other narratives contributed to the feeling among some in various black communities that including Jim Jones’ name on any memorial disrespected the victims and indicated if not a racist attitude, then a lack of racial sensitivity. The deaths of so many African Americans required some sort of political statement of opposition, and excluding Jones’ name seemed to serve this purpose. Nevertheless, a number of African Americans wrote letters to Evergreen Cemetery in support of mounting the plaques with Jones’ name, while a number of whites wrote in protest.

Separate but important considerations contributing to the fissures that existed between partisans of the different memorials were those of black religious and funerary traditions. Bishop Norwood’s memorial services strongly reflected the African American church in appearance and content. Gospel songs, prayers, “amens” from the audience, and the frequent invocation of the divine made it clear that this was a religious, rather than secular, commemoration. A visitor to the memorial service in 2018 described it as “evangelically focused and exclusive.” She continued: “The entire service was very much like a Pentecostal black church with strong, rousing sermonizing, singing and dancing.”[43]

This approach is at odds with the sentiments of many survivors. The religious elements of Peoples Temple all but disappeared in Guyana. Individual members may well have retained deep Christian faith, but overall, survivors did not wear their religion, or irreligion, on their sleeves. Some became committed Christians, others devout atheists. An absence of overt religious symbols and language characterized the survivors’ memorial services, although some individuals did in fact pray or use religious language when talking about loved ones.

Black funerary traditions may also have contributed to the disconnect between the two groups wanting to memorialize the dead. As noted above, the Guyana Emergency Relief Committee insisted on burial, rather than cremation, as part of black church traditions. In her analysis of African American funeral rituals, English professor Karla FC Holloway described the dramatic, and even theatrical, emotionalism her informants reported of black funerals. She observed more touching, kissing, and involvement with the body than at white funerals.[44] When Bishop Norwood displayed the monoliths at her service in 2008, a number of African Americans not only laid flowers upon them, they also hugged or touched the stones themselves. Photographs show some weeping in the background. As Rosaldo notes, “people express their grief in culturally specific ways,”[45] thus the overtly emotional displays at the Norwood services contrast with the quiet, introverted memorials held by survivors; this disparity may well be due to race and the cultural expectations of behavior at funerals and memorial services.

Conclusions

Jelin assesses the difficulties in memorializing the past, especially when it has been traumatic, as in the cases of the experiences under brutal dictatorships in South America in the twentieth century. What are the standards? Who is the authority? And more to the point, “Who embodies true memory.”[46] Disagreement over erecting a monument for those who died in Jonestown was unavoidable, given the disputed nature of the deaths and the various interests at play. As a partisan in the quarrel, I believe that listing everyone, rather than excluding some, was the right thing to do. I did not want to see anyone’s anger (my own included) engraved in stone. Excluding Jim Jones’ name would have meant accepting a comfortable narrative that grossly simplifies a very complex tale. His presence would have been larger, not smaller, by his omission. Now he is no larger than any other individual who was part of Peoples Temple.

Jelin introduces two terms for the word “us” from the indigenous Guarani language used daily by people in Paraguay. One, ore, “marks the boundary separating the speaker and his or her community from the ‘other,’ the one who listens and observes.” The other, ñande, “is an inclusive ‘us’ that invites the interlocutor to be part of the community.”[47]The wish to embrace only the Jonestown innocent is understandable. But that seems to me to comprise a small “us” rather than an expansive one. It is unquestionably easier, however, to be expansive from a position of privilege than one of disprivilege.

This consideration of “us”—insiders and outsiders, ethnographers and subjects—gets to the point of Rosaldo’s attempt to remake analysis in the social sciences. If we consider ritual, along with narratives, practices, and habits, as a busy intersection, we indeed find “a space for distinct trajectories to traverse.”[48] The complexity of real life demands such openness. At the same time, the specific reality of bereavement and grief challenges that approach. Rosaldo criticizes the way that “most ethnographic descriptions of death stand at a peculiar distance from the obviously intense emotions expressed, and they turn what for the bereaved are unique and devastating losses into routine happenings.”[49]

The work of memorializing the Jonestown dead is ongoing. In 2018, a reconstituted Jonestown Memorial Fund raised money to completely refurbish the site for the fortieth anniversary. Attractively colored pressed concrete replaced ragged dirt and grass, while the plaques themselves were lined with white rock; the names engraved in stone were highlighted to make them more readable. A pillow marker was installed that noted the May 2011 dedication of the memorial, and a small QR symbol was placed on it to direct visitors with smart devices to a website that featured photos of all who died in Jonestown.[50] In 2019, a complete listing of where all the dead are buried was posted to the Alternative Considerations website, since fewer than half the fatalities are interred at Evergreen Cemetery.[51]

Renato Rosaldo is right—none of this process has become routine for the survivors. Fortunately, I have been able to communicate this view to a wide audience because of my unique social position as both an insider and an outsider. By incorporating personal insights into professional assessments of bereavement processes I have attempted to enlarge public understanding of the events of Jonestown, just as Rosaldo enriched our understanding of Ilongot rituals by relating them to the experience of his wife’s tragic death. It is a tricky line to walk between the emic and the etic, but it is definitely worth the attempt.

Endnotes

[1] Renato Rosaldo, Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis (Boston: Beacon Press, 1993).

[2] Rosaldo, Culture and Truth, 11.

[3] Rosaldo, Culture and Truth, 44.

[4] Rebecca Moore, “Taking Sides: On the (Im)possibility of Participant-Observation,” In The Insider/Outsider Debate: New Perspectives in the Study of Religion, ed. George D. Chryssides and Stephen E. Gregg, 151–170 (Sheffield, UK: Equinox, 2019).

[5] Rosaldo, Culture and Truth, 15.

[6] Elizabeth Jelin, State Repression and the Labors of Memory (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 44.

[7] Jelin, State Repression and the Labors of Memory, 44.

[8] Rosaldo, Culture and Truth, 29.

[9] David Chidester, “Rituals of Exclusion and the Jonestown Dead,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 56, no. 4 (Winter 1988): 681–702.

[10] “What Pathologists Investigated the Deaths that Occurred in Jonestown, Georgetown, and Port Kaituma?” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple (2018), accessed 7 January 2019.

[11] Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concept of Pollution and Taboo (London: Routledge, 1966).

[12] Chidester, “Rituals of Exclusion and the Jonestown Dead,” 687–691.

[13] Chidester, “Rituals of Exclusion and the Jonestown Dead,” 691.

[14] Arnold Van Gennep, The Rites of Passage, trans. Monika B. Vizedom and Gabrielle L. Caffee (London: Routledge, 1960 [1908]).

[15] Chidester, “Rituals of Exclusion and the Jonestown Dead,” 693–694.

[16] Rosaldo, Culture and Truth, 46–48.

[17] Rebecca Moore, “The Stigmatized Deaths in Jonestown: Finding a Locus for Grief,” Death Studies 35, no. 1 (2011): 42–58. Also, here.

[18] Rebecca Moore, “Last Rights,” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple (1988). Accessed 7 January 2019.

[19] Erika Doss, Emotional Life of Contemporary Public Memorials: Towards a Theory of Temporary Memorials (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2008), 7.

[20] Erika Doss, Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 216.

[21] Doss, Memorial Mania, 152.

[22] Jonathan Z. Smith, Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), 109.

[23] Daniel Sherman, “Bodies and Names: The Emergence of Commemoration in Interwar France,” The American Historical Review 103, no. 2 (April 1998), 447.

[24] Sherman, “Bodies and Names,” 456.

[25] Doss, Memorial Mania, 152.

[26] Jelin, State Repression and the Labors of Memory, 33–34, italics in original.

[27] Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, Special Collections at San Diego State University, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/.

[28] “Who Died?” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, Special Collections at San Diego State University.

[29] Rebecca Moore, “Godwin’s Law and Jones’ Corollary: The Problem of Using Extremes to Make Predictions,” Nova Religio, 22, no. 3 (November 2018): 145–154.

[30] Fielding McGehee, “Jim Jones’ Name on the Marker: A Discussion of the Committee’s Decision,” the jonestown report 13 (October 2011).

[31] Margalit, The Ethics of Memory, 37.

[32] Margalit, The Ethics of Memory, 44.

[33] Margalit, The Ethics of Memory, 73.

[34] “Eight Revolutionaries,” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple (2015 [1973]). accessed 31 December 2018.

[35] Margalit, The Ethics of Memory, 42.

[36] Margalit, The Ethics of Memory, 43.

[37] David Chidester, Salvation and Suicide: An Interpretation of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple and Jonestown (Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 1988), 42–43.

[38] Lear K. Matthews and George K. Danns, “Communities and Development in Guyana: A Neglected Dimension in Nation Building” (Georgetown, Guyana: University of Guyana, 1980); reprinted as “The Jonestown Plantation” in A New Look at Jonestown: Dimensions from a Guyanese Perspective, ed. Eusi Kwyana (Los Angeles: Carib House, 2016), 82–95; C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence Mamiya, “Daddy Jones and Father Divine: The Cult as Political Religion,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 2004 [1980]), 28–46; Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, eds., Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America (Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 2004).

[39] Ethan Feinsod, Awake in a Nightmare: Jonestown, the Only Eyewitness Account (New York: W. W. Norton, 1981); Kenneth Wooden, The Children of Jonestown (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981).

[40] “Demographics at a Glance,” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple (2017), accessed 11 January 2019.

[41] Sikivu Hutchinson, “No More White Saviors: Jonestown and Peoples Temple in the Black Feminist Imagination,” the jtr bulletin (2014).

[42] Sikivu Hutchinson, White Nights, Black Paradise (Los Angeles: Infidel Press, 2015).

[43] Joy Valentini, email communication, 3 January 2019.

[44] Karla FC Holloway, Passed On: African American Mourning Stories (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 154–155.

[45] Rosaldo, Culture and Truth, 58.

[46] Jelin, State Repression and the Labors of Memory, 43, italics in original.

[47] Jelin, State Repression and the Labors of Memory, 43.

[48] Rosaldo, Culture and Truth, 17.

[49] Rosaldo, Culture and Truth, 57.

[50] See jonestownmemorial.com.

[51] “Where are the Jonestown Dead Buried?” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple accessed 16 January 2021.

Bibliography

Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple.

Chidester, David. “Rituals of Exclusion and the Jonestown Dead.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 56, no. 4 (Winter 1988): 681–702.

Chidester, David. Salvation and Suicide: An Interpretation of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 1988.

“Demographics at a Glance.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple (2017). Accessed 11 January 2019.

Doss, Erika. Emotional Life of Contemporary Public Memorials: Towards a Theory of Temporary Memorials. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2008.

Doss, Erika. Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concept of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge, 1966.

“Eight Revolutionaries”. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple (2015 [1973]). Accessed 31 December 2018.

Feinsod, Ethan. Awake in a Nightmare: Jonestown, the Only Eyewitness Account. New York: W. W. Norton, 1981.

Holloway, Karla FC. Passed On: African American Mourning Stories. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.

Howard, Lela. “Jonestown Relative Announces New Foundation.” the jonestown report, 9 (2007).

Hutchinson, Sikivu. “No More White Saviors: Jonestown and Peoples Temple in the Black Feminist Imagination.” the jtr bulletin (2014).

Hutchinson, Sikivu. White Nights, Black Paradise. Los Angeles: Infidel Press, 2015.

Jelin, Elizabeth. State Repression and the Labors of Memory. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Lincoln, C. Eric and Lawrence Mamiya. “Daddy Jones and Father Divine: The Cult as Political Religion.” In Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America. Edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, 28–46. Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 2004 [1980].

Margalit, Avishai. The Ethics of Memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Matthews, Lear K. and George K. Danns. “Communities and Development in Guyana: A Neglected Dimension in Nation Building” (Georgetown, Guyana: University of Guyana, 1980); reprinted as “The Jonestown Plantation” in A New Look at Jonestown: Dimensions from a Guyanese Perspective, ed. Eusi Kwyana, 82–95. Los Angeles: Carib House, 2016.

McGehee, Fielding. “Jim Jones’ Name on the Marker: A Discussion of the Committee’s Decision.” the jonestown report13 (October 2011).

Moore, Rebecca. “Godwin’s Law and Jones’ Corollary: The Problem of Using Extremes to Make Predictions.” Nova Religio, 22, no. 3 (November 2018): 145–154

Moore, Rebecca. “Last Rights.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple (1988). Accessed 7 January 2019.

Moore, Rebecca. “The Stigmatized Deaths in Jonestown: Finding a Locus for Grief.” Death Studies 35, no. 1 (2011): 42–58. Also here.

Moore, Rebecca. “Taking Sides: On the (Im)possibility of Participant-Observation.” In The Insider/Outsider Debate: New Perspectives in the Study of Religion. Edited by George D. Chryssides and Stephen E. Gregg, 151–170. Sheffield, UK: Equinox, 2019.

Moore, Rebecca, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, eds. Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America. Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 2004.

Rosaldo, Renato. Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston: Beacon Press, 1993.

Sherman, Daniel. “Bodies and Names: The Emergence of Commemoration in Interwar France.” The American Historical Review 103, no. 2 (April 1998): 443–466.

Smith, Jonathan Z. Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

Valentini, Joy. Email communication. 3 January 2019.

Van Gennep, Arnold. The Rites of Passage. Trans. Monika B. Vizedom and Gabrielle L. Caffee. London: Routledge, 1960 [1908].

Wooden, Kenneth. The Children of Jonestown. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981.

“What Pathologists Investigated the Deaths that Occurred in Jonestown, Georgetown, and Port Kaituma?” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple (2018). Accessed 7 January 2019.

(Rebecca Moore is Professor Emerita of Religious Studies at San Diego State University. She has written and published extensively on Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Rebecca is also the co-manager of this website. Her other articles in this edition of the jonestown report are Bringing Release, Finding Peace: Memories of Vernon Gosney; George Donald Beck; InTOXICating Followership: A Review; and Spreadsheet Offers Downloadable Demographic Tool for Researchers. Her collection of articles on this site may be found here. She may be reached at remoore@sdsu.edu.)