(Edward Cromarty is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. His other article in this edition is The Failures in Depicting Jonestown in Film. His complete collection of articles is here. He can be reached at edwardcromarty@hotmail.com.)

Introduction

The lessons of Jonestown are many and profound, but they are not limited to the implications of its dramatic demise. Rather, many come from the life of the community, not its death. Whether we consider the community’s vocational training and education systems, its medical services or its artistic expressions, some of the agricultural commune’s methods were ahead of their time and are even now considered to be cutting-edge practice, even experimental in nature. Understanding the success of some of these progressive, innovative methods allows us to consider how they can be used to improve the lives of people in our present world.

Context

Although there was a loss of records following the events that occurred in Guyana, the records that remain provide an excellent record of life in Jonestown. In addition, we have the first-hand collective memory of its members, particularly of children who are valued for their innocence of testimony, and the honesty in which events are told. As the memories of survivors were archived, they became the cultural memory of the Jonestown commune. The experiences and testimonies of survivors served to moderate emotions which may blur the objectivity of researchers and the profit motivations of corporate media.

At its core, the Jonestown Agricultural and Medical Project was a utopian socialist community dedicated to the establishment of social equity and racial harmony. It differed from other communal projects established in Latin America at the time in its focus on an activist brand of socialism as a means of establishing racial, gender, and economic equality. This is reflected in its demographics: Jonestown was comprised primarily of women (64% of the Temple’s population in Guyana on November 18, 1978), children and elderly (combining for 56.5%), and African American (70%) (Moore, 2017). A large proportion had working-class backgrounds (Cromarty, 2013).

At its core, the Jonestown Agricultural and Medical Project was a utopian socialist community dedicated to the establishment of social equity and racial harmony. It differed from other communal projects established in Latin America at the time in its focus on an activist brand of socialism as a means of establishing racial, gender, and economic equality. This is reflected in its demographics: Jonestown was comprised primarily of women (64% of the Temple’s population in Guyana on November 18, 1978), children and elderly (combining for 56.5%), and African American (70%) (Moore, 2017). A large proportion had working-class backgrounds (Cromarty, 2013).

Jonestown was favored and chartered by the cooperative socialist Guyanese government which was attracted by Peoples Temple’s emphasis on racial equality to assist in the agricultural, educational, and medical development of Guyana’s sparsely-populated Northwest District. Its socialist communal beliefs and work-based practices differentiated Jonestown. The inclusive activity-based concepts of an ethnically diverse community were revolutionary in their time and are still evolutionary in modern practice.

As a small activist organization, the Temple struggled first to change the world, and later to remove itself from mainstream society, which it considered to be racist and socially unjust. Based on socialist principles, Peoples Temple – both in California and Guyana – became a target of persecution from conservative ideologues seeking to repress issues of racial and social equality. This criticism on a personal and organizational level increased the isolation of Jonestown and its residents resulting in a radicalization of beliefs. The residents; sense of persecution was also grounded in their own experience with past discrimination. Because it was a small flexible community, the ability of Jonestown to act and think in creative ways, the human effects of persecution, and the influence of Jim Jones as an authoritative figurehead furthered its inward-looking tendencies. The people of Jonestown were proud of their contributions to society and found it difficult to understand insensitive criticisms too often based on prejudice and profit motivations.

But part of the resistance from established social organizations reflected the fact that Jonestown was employing new and controversial alternative techniques of community building.

The Arts, Photography, Literature, and Community

The Arts, Photography, Literature, and Community

The social interactions and emotions of a community are most often apparent in its artistic expressions. An examination of the literature and arts of Jonestown provide a window to daily life within the commune. They show the culture of an alternative community based on utopian socialist beliefs that developed from the realities and practical considerations of living in the Guyanese jungle. The evolution of new values based on the experience of Jonestown, which differed from mainstream culture, should be viewed as positive adaptations to life in the commune and its contributions to the local Guyanese communities.

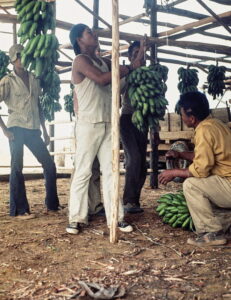

The photography which captured the daily life of Jonestown, for example, depicts a community working together in moments of play and industry. Rather than focusing on the leadership activities – of which there are surprisingly few photos – its portraits emphasize Jonestown’s daily activities such as agricultural labor, school children at study, medical staff treating people, craftspeople constructing the community, and social group events (Cromarty, 2015). We have inherited a visual record that illustrates a creative and vibrant racially integrated community which made Jonestown unique in its time and continues to provide an example to modern social planners and educators.

The writings of Jonestown, ranging from family letters to the stories and poems of both children and adults, also present elaborate descriptions of the colorful vegetation, wildlife, pristine environment, and healthy tropical food provided by the jungle (Cromarty, 2017). Portrayals of the natural beauty of the jungle are particularly acute in the writings of the children, in comparison to the writings of adults who had migrated to Jonestown from the US and placed a higher value on the mission of equality and social justice upon which Jonestown was founded. This blending of environmental and social justice stands out as a seminal precursor in the development of social issues involving environmental equality.

Arts and crafts were practiced in the school and in community education as a practical tool relevant to the social and economic development of the community. Industrial arts and crafts – such as woodworking and metallurgy – were made relevant to the social good through the production of useful items of candles, soaps, and stuffed toys. A creative work-based concept of the arts was taught through productive activities, for example children making their own tools and materials to be used in the school as class assignments. The Jonestown school recognized the importance of the creative growth of its students, and its community programs offered languages, writing, music, arts, and crafts to all residents. An essential foundation of all of these efforts was a work-study concept that emphasized the productive utilization of local indigenous materials and culture (Progress Report Summer 1977; Jonestown: A model of Cooperation, 1978; Cromarty, 2020).

Education and Vocational Training

Education and Vocational Training

The project also emphasized community-based work training programs and free medical care. Jonestown practiced an early form of inclusive vocational activity-based training which is still in development in education today. On-the-job training was provided in useful vocations from carpentry to medicine. In California, Peoples Temple provided affordable medical education through the state colleges. The letter and diaries of Annie Moore provide a glimpse into the experiences of a young nurse educated through the Temple and trained in the Jonestown medical facilities (Cromarty, 2010). Being both advanced for rural Guyana and free, the Jonestown medical facilities were of great benefit to surrounding communities.

Other writings from both residents and visitors describe the Jonestown school as an early example of an inclusive community-based school without walls that provided academic education and vocational training to both the people of Jonestown and their neighbors (Guyana Chronicle, June 19, 1978; Cromarty, 2020). Accredited and established within the cooperative socialist education and political system of the Guyanese government, the Jonestown school was an early example of education in a system which has been developed and transformed for use in present day Caribbean education, because it addressed the social difficulties and needs of the people of the region.

Education and vocational training in Jonestown utilized a non-linear experiential-based system which inclusively served the needs of the entire community and nurtured the growth of a socialist mindset. Education and training in Jonestown included the academic, community education, and vocational training in skills of value to the community for example nursing, building crafts, agriculture, and medicine. Vocational training utilized on-the-job employment under the tutelage of experienced craftspeople. Teachers were highly skilled professionals often trained in the United States with continuing training in Jonestown. In Jonestown, the educational practices successfully motivated students who had been cast aside by the standardized limitations of education in the US.

The method of education utilized in Jonestown was a system purposely designed to work within Guyana’s political system. Students made educational tools using creative production to overcome their lack of financial and material facilities. They used indigenous materials sourced from the local fauna and culture such as desks, perhaps the first white boards for use with charcoal, pencils, and playgrounds. Skilled professionals from Jonestown and the local Guyanese communities, particularly native Amerindians, taught survival and industrial techniques that would improve success in the tropical environment.

The method of education utilized in Jonestown was a system purposely designed to work within Guyana’s political system. Students made educational tools using creative production to overcome their lack of financial and material facilities. They used indigenous materials sourced from the local fauna and culture such as desks, perhaps the first white boards for use with charcoal, pencils, and playgrounds. Skilled professionals from Jonestown and the local Guyanese communities, particularly native Amerindians, taught survival and industrial techniques that would improve success in the tropical environment.

The community also took advantage of the unique resources of its elderly population which passed along their experience in telling stories and teaching lessons in their areas of expertise. Age, gender, and racial integration taught students the human skills of working with all ages, ethnic backgrounds, experience levels, and gender equality. The totality of these methods were not only cutting-edge in the 1970’s, they continue to be at the forefront of progressive education at a time in which schools are struggling with excessive violence, racism, and the exclusionary barriers created by standardized programs and high stakes testing.

Jonestown as a radical experiment in socialist communal living creatively applied new theories which were revolutionary in the 1970’s, some of which continue to be controversial today. The jungle community was ahead of its time in applying concepts of social justice and racial equity. It was visionary in applying new theories of human behavior, most notably in education, vocational training, and medicine which required highly skilled professionals. The educational techniques systematically practiced in Jonestown in the 1970’s preceded their use in American schools and universities by decades.

In the sciences, medical care was free and of high quality, an objective that American healthcare, mired in the corruption of corporate politics, is far from achieving. It explored new techniques of growing crops in the tropical climate, and the productive use of the arts and crafts.

The residents of Jonestown worked hard to achieve a community based on racial and social equality. The primary belief upon which the Peoples Temple’s agricultural project was built – social and racial harmony – remains the area in which Jonestown continues to shine. In their attempt to build a community free of racial inequity, the people of Jonestown set an example that American society strives to achieve, and has not been able to emulate.

References

Cromarty, E. (2020). Indigenous materials and learning in the education programs of Jonestown. Jonestown Report, Jonestown Institute, San Diego State University, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=102135

Cromarty, E. (2017) Divergence in the writings of Jonestown. Jonestown Report, Jonestown Institute, San Diego State University, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=67361.

Cromarty, E. (2015). A review of the photography of Jonestown. Jonestown Report, Jonestown Institute, San Diego State University, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=64904.

Cromarty, E. (2013). Integrity and Jonestown research. Jonestown Report, Jonestown Institute, San Diego State University, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=40213.

Cromarty, E. (2010). Effects of isolation on the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project. Jonestown Report, Jonestown Institute, San Diego State University, (Part I) https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=30236.

Jonestown: A Model of Cooperation (1978). Peoples Temple Agricultural Project. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple.

Moore, Rebecca (2017). An Update on the Demographics of Jonestown. Jonestown Report, Jonestown Institute, San Diego State University. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=70495.

Peoples Temple Gets Official Status. (19 June 1978). Guyana Chronicle.

Progress Report-Summer 1977 (1977). Peoples Temple Agricultural Project. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple.