[Editor’s note: This article is part of a special report by the November 18 Project. The table of contents for the report is here.]

The Death Tape is a 44-minute audio recording made in Jonestown, Guyana, on November 18, 1978. The tape documents the final gathering of Peoples Temple as Jim Jones urges his followers to take their lives for what he refers to as “revolutionary suicide” by ingesting a cyanide-laced potion. Fragmented by frequent edits and the emotions of the participants, Temple members waver between doubt and devotion as the children are poisoned. Historically viewed as a testament to Jim Jones’ unchecked power at Jonestown’s most critical moment and a devastating record of the murder/suicide of 909 people, the Death Tape provides invaluable historical insight into how events unfolded during Jonestown’s final moments.

The “last hour tape,” commonly referred to as the Death Tape, was found on November 24, 1978 by Richard Martin, the Vice Consul of the United States Embassy, as he toured the aftermath of Jonestown. A seven-inch reel-to-reel tape still wound onto the spindles of an open reel recorder and tethered to a microphone found at the foot of Jim Jones’ chair on the stage in the pavilion. Upon its discovery, Major Richard T. Helmling, an Army intelligence officer, told me in an interview that someone pointed to the recorder and said, “I think that SOB recorded it.”

Unable to connect the reel-to-reel machine to a power source in Jonestown, they took it into evidence and transported it to the U.S. Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana. Major Helmling remembered U.S. Ambassador John Burke played the tape for the first time in the presence of Helmling, Martin, and another unidentified embassy official. Concerned about potential legal implications, Ambassador Burke instructed Major Helmling to handle the matter on a strictly need-to-know basis, “and no one needs to know.”

*****

On December 4, 1978 U.S. Embassy personnel and FBI agents listened to the tape for the first time. I spoke with United States Consul Douglas Ellice, who recounted the tense atmosphere at the embassy due to persistent rumors of Peoples Temple hit squads in the weeks following the tragedy. Twenty people packed in a room sitting on chairs, tables and even the floor of the small embassy. Bunkered down with the windows shuttered, they struggled to piece together the catastrophe that led to the death of nearly one thousand Americans they were stationed in Guyana to protect. Ellice hadn’t been stationed in Guyana long. Earlier that November, he visited Jonestown as part of his embassy duties and found a bustling egalitarian community. He observed that the residents of Jonestown looked healthy and remarked on Jim Jones’ apparent ill health and disturbing appearance in a gauze mask during their meeting.

On December 4, 1978 U.S. Embassy personnel and FBI agents listened to the tape for the first time. I spoke with United States Consul Douglas Ellice, who recounted the tense atmosphere at the embassy due to persistent rumors of Peoples Temple hit squads in the weeks following the tragedy. Twenty people packed in a room sitting on chairs, tables and even the floor of the small embassy. Bunkered down with the windows shuttered, they struggled to piece together the catastrophe that led to the death of nearly one thousand Americans they were stationed in Guyana to protect. Ellice hadn’t been stationed in Guyana long. Earlier that November, he visited Jonestown as part of his embassy duties and found a bustling egalitarian community. He observed that the residents of Jonestown looked healthy and remarked on Jim Jones’ apparent ill health and disturbing appearance in a gauze mask during their meeting.

Less than a month later, sitting on the floor of the dark embassy with his back against the wall, Ellice listened as the community fell apart and Jim Jones made his last speech.

The tape begins with Jim Jones telling his followers that Congressman Leo Ryan’s plane was going to fall out of the sky and that soon the Guyana Defense Force would be sending troops to parachute into Jonestown and torture and kill their children.

A lone dissenter, Christine Miller, advocates for the lives of the children and suggests they go to Russia. As the discussion becomes more heated, several voices in the crowd argue with Christine. A tractor returns from the Port Kaituma carrying Temple members who just participated in the airstrip shooting. Jim Jones announces that Congressman Ryan and members of his delegation have been killed at the airstrip and orders the poisoning of the children to begin. As Temple members give testimony to the righteousness of Jim Jones and the beauty of death, the sounds of children crying overpower the recording. Jim Jones becomes agitated and admonishes his followers to step over quietly. A woman cries out and Jim Jones scolds her, telling her to lay her life down with her child. Various Temple members speak, expressing support for their collective decision to die. Jim Jones orders a vat of cyanide-laced potion for the adults. As the sounds heard in the background of the recording become more strained and chaotic, Jim Jones makes his final statement: “We didn’t commit suicide; we committed an act of revolutionary suicide protesting the conditions of an inhumane world.”

Ellice recounted that listening to the tragedy unfold was possibly the worst hour of his life. Using the tape, investigators were able to piece together a timeline of the night of the 18th and gain a better understanding of how and why the tragedy happened. The Death Tape corroborated details found in the eyewitness accounts of Odell Rhodes and Stanley Clayton, who had both escaped Jonestown during the murder/suicide. Voices on the tape provide an unflinching record that not everyone in Jonestown wanted to die, while others took the poison willingly.

Initially, the State Department maintained custody of the tape and it was placed in the safe of the Ambassador Burke at the embassy. The tape was then removed from the safe to be reviewed by embassy officials and FBI agents. Copies of the tape were made for both the FBI and the Government of Guyana (GOG). The GOG complained about the poor audio quality of the tape. Eventually, FBI lab technicians developed a cleaner copy of the tape to aid in their investigation into the murder of Congressman Ryan and officially logged the tape as lab specimen, “Q042.”

US Ambassador John Burke and U.S. Attorney General Griffin Bell stated that they did not support the release of the Death Tape to the public, likely due to its evidentiary value. Despite the U.S. Government’s desire to withhold the tape, a copy eventually leaked to the media. Who released the tape to the media remains a mystery.

*****

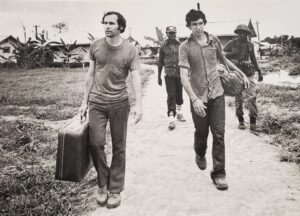

Mike Prokes was in Jonestown on the night of November 18th. He fled with Tim and Mike Carter on a mission to deliver Temple documents and money to the Soviet Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana. In December 1978, Mike Prokes travelled to Matthews Ridge, a small village located approximately 30 miles from Jonestown, to testify in the Guyana Inquest, the GOG’s official inquiry into the deaths at Jonestown. While there, Mike Prokes spoke to Charles English, a U.S. embassy official who had listened to the Death Tape. Later, Mike Prokes wrote:

Mike Prokes was in Jonestown on the night of November 18th. He fled with Tim and Mike Carter on a mission to deliver Temple documents and money to the Soviet Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana. In December 1978, Mike Prokes travelled to Matthews Ridge, a small village located approximately 30 miles from Jonestown, to testify in the Guyana Inquest, the GOG’s official inquiry into the deaths at Jonestown. While there, Mike Prokes spoke to Charles English, a U.S. embassy official who had listened to the Death Tape. Later, Mike Prokes wrote:

Charles English described parts of the tape to myself, Tim Carter and two reporters whose names I can’t recall. Probably the most significant thing he said was that he thought the tape would never be played publicly because it would be an embarrassment to the United States. He said it reveals that the people of Jonestown were not coerced into taking their lives, but rather the deaths resulted basically from a collective decision based upon the perception that the community was doomed and there was no use to continue. English said that while he and a number of others were listening to the tape in Georgetown, U. S. Ambassador John Burke came into the room and also listened to it. When it was finished, Burke told those in the room, in no uncertain terms, that they had better not breathe a word of what they heard. He then took the tape into his personal custody.

Guyanese Assistant Police Commissioner Cecil “Skip” Roberts also described to Mike Prokes what he had heard on the tape, going beyond what English had said. Mike Prokes wrote:

Skip Roberts told me in a private conversation, the day before I left Guyana, that the tape showed solidarity of the people of Jonestown. He said he was deeply moved by what he heard. He said that if he were in Jonestown at the time of the deaths, he could see how he would have willingly died with the people, had he been part of the community. Moreover, he told me he believed there was some outside plan to destroy Jonestown.

On December 8 and 9, a federal Grand Jury began hearing testimony from eyewitnesses, and The Washington Post and the New York Times published articles about the Death Tape, accurately quoting the recording.

*****

On March 13, 1979, Mike Prokes called a press conference in a Modesto motel room. With an audience of eight journalists, Prokes made a statement that in part focused on the Death Tape. Prokes believed the tape would never be released to the public because its contents would embarrass the U.S. Government. At the conclusion of his statement, Prokes went into the motel bathroom, turned on the faucet, and shot himself. A note was found nearby that read:

Don’t accept anyone’s analysis or hypothesis that this was the result of despondency over Jonestown. I could live and cope with despondency. Nor was it an act of a ‘disturbed’ or ‘programmed’ mind – in case anyone tries to pass it off as that. The fact is that a person can rationally choose to die for reasons that are just, and that’s just what I did. If my death doesn’t prompt another look at what brought about the end of Jonestown, then life wasn’t worth living anyway.

On March 14, 1979, a day after Mike Prokes’ suicide, the Death Tape was leaked to the public through the media. The National Enquirer came into possession of what they thought might be a copy of the Death Tape and asked the Michigan State Police Voice Identification Unit in East Lansing to confirm its authenticity. NBC’s Today Show broadcasted segments of the recording beginning on March 14, and continued playing the tape off and on for three days. Less than a week later, International Home Video Club, Inc., announced they had obtained the tape and planned to reproduce it commercially for $9.95 a tape. Beau Buchanan, founder of the International Home Video Club Inc., claimed that he obtained the tape from “someone in Guyana” shortly after the deaths in Jonestown but never identified his source. Researchers have speculated the tape circulated by IHVC may have been a copy of a copy the FBI made for the Guyana Government due to its poor audio quality. Years later, a higher-quality digitized version of the tape was uploaded to the Internet Archive by a sound engineer named Olen Sluder, who claimed he acquired the tape in 1979 from a schoolmate whose father was an FBI agent.

A spokesman for the FBI and Christopher Nascimento, Guyana’s Minister of State, told the New York Times that the Death Tape had been withheld because of investigations in progress. Nevertheless, in December 1978 senior Guyanese Government officials claimed that they had been denied permission to play the tape at the Guyana Inquest because of a very “delicate” political matter. Prokes was adamant in his final statement prior to his death that the Death Tape would forever change people’s perceptions of Jonestown. Despite having likely never heard the tape, Prokes’ prediction was correct.

*****

Throughout the years, researchers have puzzled over audio anomalies found on the tape. Ghostly organ music plays throughout the tape at the wrong pitch and speed. Mysterious shortwave radio messages bleed through, sometimes playing in reverse. As many as 80 audible edits leave parts of the death tape feeling fragmented and incomplete and led to speculation that the tape was edited as part of a diabolical conspiracy to hide the truth about Jonestown or to obscure the facts. At face value, without context, the Death Tape is mystifying. Owing to the due diligence of a handful of researchers, many of the Death Tapes’ mysteries have been resolved.

Thanks to the research of Josef Dieckman, Joel X. Thomas, Kyle Ray and Amanda Veazey, we now know that the ghostly organ music heard on the tape is previously recorded, commercially produced music. Tapes were often recycled and reused in Jonestown creating audio artifacts and strange irregularities. Joel X. Thomas theorized that because the reel-to-reel recorder used on the night of the 18th had a misaligned eraser head, the previously recorded music was partially recorded over, blending both the new and old recordings together. The organ music is pitched down and distorted because of the difference in speed at which the original audio was recorded. Joel X. Thomas was able to identify three of the songs heard in the background of the Death Tape by speeding up the recording: “I’m Sorry” by the Delfonics; “The Pain Gets a Little Deeper” by Darrow Fletcher, and “Never Give You Up” by Jerry Butler.

Like an impassive, automated spectator, the reel-to-reel hummed away while Jim Jones silently controlled the recording, either by muting the microphone in his hand or signaling to an accomplice operating the audio equipment when to stop and resume the taping. Jim Jones carefully managed what was recorded on Q042. His message was intentional, and anything he wished to conceal was left unrecorded. You can hear edits when the tape machine itself is stopped mid-recording and the speed and pitch of the audio are affected. Two microphones were used and there are audible moments on the Death Tape when the tape is still recording but the microphones have been turned off or muted.

Tim Carter was in Jonestown as the Death Tape was being recorded. He shared with me that before he left Jonestown with his brother, Mike, and Mike Prokes, he remembered Marceline Jones crying out in protest as children were dying, yet that moment is missing from the Death Tape. Unlike the edits you hear as people are speaking, the ghostly background music plays uninterrupted. This suggests that if the background music can be heard on the original 7-inch reel-to-reel recording, the Death Tape we hear today is likely identical to what Douglas Ellice heard all those decades ago. In short, any edits to Q042 likely occurred while it was being recorded, not after it was recovered by the U.S. Government.

The strange shortwave radio messages heard on Q042 have been deciphered and their origin explained. Due to the proximity of Jonestown’s radio room to the reel-to-reel recording device, shortwave radio messages bled through unshielded wiring as recordings were being made. Sometimes radio messages appear on recycled tapes and are played back in reverse and at a lower pitch, not unlike the ghostly background music heard on Q042. This radio bleed anomaly can be heard on several tapes available in the Jonestown Institute’s audio archive in addition to the Death Tape.

Perhaps the most controversial oddity found on the Death Tape happens around the time the tractor carrying the “Red Brigade” returns from the Port Kaituma airstrip. Jim Jones is heard ordering Jonestown’s security to take Deputy Chief of Missions for the U.S. Embassy, Richard Dwyer, to the “East House.” Voices in the crowd respond to the order with confusion, but Jim Jones reiterates by saying, “get Dwyer out of here.”

Richard Dwyer accompanied Congressman Ryan to the Port Kaituma airstrip on the evening of November 18th. He was injured during the airstrip shooting and helped organize the medical evacuation for the survivors the next day. FBI interviews with eyewitnesses account for Dwyer’s whereabouts throughout the night in Port Kaituma. Why did Jim Jones think Richard Dwyer had returned to Jonestown with the Temple assassins?

Richard Dwyer accompanied Congressman Ryan to the Port Kaituma airstrip on the evening of November 18th. He was injured during the airstrip shooting and helped organize the medical evacuation for the survivors the next day. FBI interviews with eyewitnesses account for Dwyer’s whereabouts throughout the night in Port Kaituma. Why did Jim Jones think Richard Dwyer had returned to Jonestown with the Temple assassins?

Tim Carter witnessed the confusion over Dwyer as the Death Tape was recorded. He explained that on the afternoon of the 18th, Congressman Ryan intended to stay in Jonestown another night. Several Jonestown residents came forward during Ryan’s visit and asked him to help them get out of Jonestown. Dwyer used the shortwave radio in Jonestown to request a second plane to carry defectors to Georgetown. An emotional disagreement between the Simon family erupted when Al Simon and his father, Jose, attempted to put two of his three children on the truck as it prepared to leave Jonestown. Bonnie Simon, Al’s wife, panicked when she realized that her children might be taken without her permission. Congressman Ryan resolved to stay in Jonestown one more night to ensure anyone who wished to leave the following day would have his protection.

As Ryan discussed the events of the day with Jim Jones in the pavilion, Temple member Don Sly attacked Ryan with a knife. Congressman Ryan was not injured, but after some discussion, it was decided that his presence in Jonestown was unsafe for everyone and Dwyer would remain in Jonestown one more night to ensure additional defectors could leave safely when the planes returned the following day. Richard Dwyer accompanied Leo Ryan to the airstrip in Port Kaituma where he reported the attempted stabbing incident and collected local law enforcement with the intention of returning to Jonestown and arresting Don Sly. He was on the airstrip during the attack.

So why does Jim Jones say, “get Dwyer out of here,” on the Death Tape if Dwyer was still in Port Kaituma? Tim Carter described the road as it entered Jonestown: if you were standing on the pavilion stage, you could hear a vehicle coming down the road before you could see it. As security guards alerted Jim Jones that they could hear the tractor returning from the airstrip, Jim Jones did not, as of yet, know what had occurred during the shooting, nor could he see who was on the tractor. He may have assumed Dwyer was on the tractor returning to Jonestown. Amidst the confusion, Tim Carter remembers Marceline Jones telling Jim Jones that Dwyer was not on the tractor and that only “our people” were aboard. This exchange is yet another important moment we do not hear on the tape.

Jim Jones spent vast amounts of energy and resources preserving Peoples Temple’s history on audiotapes, knowing they would one day be discovered by curious researchers and help shape Jonestown and Peoples Temple’s memory. Q042 remains one of the most significant audio recordings made in the 20th century. An intriguing auditory walk through of a nearly 50-year-old crime scene. Maybe the greatest mystery of the Death Tape is why it was recorded. Many researchers have shared with me that their first interactions with Temple media were listening to the Death Tape. Of all the hundreds of tapes the Temple left behind, was this the one meant to shape their legacy?

Q042 inspired my own interest in Jonestown and Peoples Temple decades ago. Determined to answer questions I had about the tape, I searched through documents, archives, interviewed eyewitnesses and State Department personnel. I forensically dissected the Death Tape and chronicled its discovery and eventual release to the public. I studied various transcripts of the Death Tape notating the differences and discoveries made by seasoned researchers over the years. The mysteries of Q042 held my fascination but the stories behind the voices heard on the tape focused my ambition as I worked to develop a comprehensive transcript.

Thanks to Fielding McGehee and the Jonestown Institute, I connected with several researchers who were also developing detailed transcripts of Q042. For the pursuit of historical truth and in an effort to identify every voice heard on the tape, we began working on the November 18th Project: a collaborative effort by dedicated researchers to produce comprehensive timelines and transcriptions documenting the events of November 18, 1978. After years of careful listening, by combining our research, we have crafted a detailed transcript of the Death Tape. When we could not agree on what we heard, we put those variations into a a spreadsheet.

This document will be periodically updated as new information becomes available. We welcome any additions or corrections to our work. radiojonestown@gmail.com

If you would like to listen to a cleaner, high quality copy of the Death Tape go either here or here.

If you use this transcript we kindly ask that you credit The Jonestown Institute and the volunteer researchers who created this document: Adrian Whicker, Shannon Howard, Joel X. Thomas, and Brian Holtz.

For more information about Jonestown’s audio infrastructure check out Joel X Thomas’ article here.

A detailed timeline following the State Department and FBI’s chain of evidence log for the Death Tape leading to its eventual leak to the public appears here.

(Shannon Howard is a researcher, audio documentarian and collector of oral histories. Her long format documentary podcast Transmissions from Jonestown. Her collection of articles for the jonestown report may be found here. She may be reached at radiojonestown@gmail.com.