(Aliah Mohmand is a student with an interest in Peoples Temple. Her interest began in 2021, and her research encouraged her to write for the Institute. She encourages any survivors with memories of the Park Hotel to please reach out. She may be reached at aliahmohmand@gmail.com.)

(Several sidebars accompany this article, including A Listing of Known Survivors Who Stayed at the Park Hotel, A Timeline of Events at the Park Hotel, and A Listing of Press Interviews with Survivors. This special section concludes with The Importance and Challenge of Preserving Jonestown Survivor Interviews, a commentary by the author.)

In an instant in November 1978, as the world learned of the tragedy of more than 900 dead in the depths of a Guyanese rainforest, the lives of hundreds – if not thousands – of Peoples Temple members and relatives became forever altered. It was also the beginning of a new life for the 87 Temple members still in Guyana: that of being survivors.

Within a couple of days of the tragedy, even as the U.S. military worked in Jonestown to repatriate the dead, around thirty survivors were airlifted from the Northwest District of Guyana – Jonestown, Matthews Ridge, and Port Kaituma – to the capital city of Georgetown, where they were eventually quarantined at the Park Hotel, a seedy colonial-era relic. There they found themselves under the scrutiny of the media and forced to deal with the unorganized response of the American and Guyanese governments, all while simultaneously attempting to process their confusion and grief.

Similar to many other aspects of the Jonestown aftermath, the dramas that unfolded within the Park Hotel are typically overlooked or forgotten, save for the occasional newspaper article or survivor interview. Even the most extensive histories of Peoples Temple and Jonestown novels – Tim Reiterman and John Jacob’s 1982 Raven, for instance – fail to acknowledge the Park Hotel’s chaotic chronicle of events and its importance in the aftermath. Considering that the history of Peoples Temple and the survivors’ stories don’t begin or end with November 18, 1978, perhaps a look at the Park Hotel might reveal some insights into that aftermath and into the perspectives of survivors.

*****

The group of about 30 survivors were not immediately transferred to the Park Hotel. Instead, as they began to return to Georgetown, they were temporarily placed under the custody of and housed in the Georgetown Police Headquarters.[1] Codenamed the “Eve Leary Headquarters” group – named after the office building of the Guyana police – this contingent of survivors comprised nearly all of the Jonestown residents and defectors who managed to escape or evade the mass deaths, with the exception of those requiring critical medical care.

The space at Eve Leary quickly reached capacity, and conditions were cramped and uncomfortable. Already, according to State Department reports, tension was alleged to have developed between three men – Tim Carter, Mike Carter, and Mike Prokes – who had been tasked by the Jonestown leadership to deliver cash-filled suitcases to the Soviet Embassy, and some of the Jonestown defectors. The presence of the trio purportedly heightened “anxiety”[2] in some of the other survivors. Awaiting word from the American and Guyanese governments on the repatriation of survivors, the Guyana police decided to transfer members of the Eve Leary group over to the Park Hotel in the interim.[3]

*****

Located along Georgetown’s Main Street, the Park Hotel was built in the 19th century during British colonial rule. Within years of its opening, the four-story Park Hotel became a monumental landmark. Despite its infamous reputation for its early policy of denying entry to non-whites,[4] the Park Hotel enjoyed a high level of popularity among Guyanese and British alike. Complementing its neighboring British colonial-style buildings, the hotel was distinguished by its wooden structure and spacious open-air veranda. Overlooking the bustling streets of Georgetown through its lattice framework and surrounded by tropical foliage, the hotel veranda was frequented by both Guyanese locals and foreign visitors.

Located along Georgetown’s Main Street, the Park Hotel was built in the 19th century during British colonial rule. Within years of its opening, the four-story Park Hotel became a monumental landmark. Despite its infamous reputation for its early policy of denying entry to non-whites,[4] the Park Hotel enjoyed a high level of popularity among Guyanese and British alike. Complementing its neighboring British colonial-style buildings, the hotel was distinguished by its wooden structure and spacious open-air veranda. Overlooking the bustling streets of Georgetown through its lattice framework and surrounded by tropical foliage, the hotel veranda was frequented by both Guyanese locals and foreign visitors.

In the years following the end of British rule – and certainly by 1978 – the hotel fell into a state of disarray and disrepair. The rooms were tiny, outdated, and unairconditioned. Water problems were a frequent recurrence. Nearly every reporter covering the tragedy who stayed there would later comment on its “seedy and shabby” condition.[5] In comparison with the newly-constructed and grander Pegasus Hotel, the Park Hotel was simply a shadow of its former self. Still, regardless of its antiquity, the Park Hotel continued to prosper as one of Georgetown’s significant hotels and as a hotspot for countless locals.

*****

The first survivors were reported to have been transferred to the Park Hotel approximately sometime between Thursday and Friday, November 23 and 24.[6] Immediately upon their arrival, survivors were met with the onslaught of the international media and press. Reporters came from all over the world, arriving from the United States, England, France, Argentina, and even as far away as Japan.[7] In large part because of the survivors’ presence at the hotel, it quickly became one of the best places a reporter could be stationed. The media scrambled to interview survivors – “cultists,” as they were invariably labeled – seeking an explanation for the inexplicable.

There was little escape for the survivors. They might have attempted to nap or pass time in their hotel rooms, desperate for relaxation, only to be interrupted by a journalist’s knock at their doors. Even without these disruptions, though, the humid, unairconditioned rooms were downright unbearable, and most eventually – reluctantly – came down to the second-floor veranda. It was there that they exposed themselves to the virulence of the press. A few – like Richard Clark and Diane Louie[8] who secretly left Jonestown early on November 18 as part of the picnic group, and elderly survivor Grover Davis – managed, for the most part, to hide out in their third-floor rooms[9] and evade most of the media’s assault, but most were not so lucky.

It was unavoidable: if someone had any connection to Peoples Temple – and especially if they had been in Jonestown during the week leading up to the deaths – they were instantly placed in the media spotlight. Of particular interest was the Parks family – Gerald; his mother, Edith; his children Dale, Brenda, and Tracy; and Brenda’s boyfriend, Chris O’Neal – who had been among the 16 defectors who left with Congressman Leo Ryan and survived the Port Kaituma airstrip shootings. As they willingly offered criticisms of Jonestown and tales of their riveting survival, the media considered them to be trustworthy and heavily featured their stories.

In one instance, a young Tracy Parks spoke of her mother’s death with a vacant stare:

“I’m not ever going to be happy again without my mother. … I’m not going to feel the same. She always took care of me. I don’t have anyone like her now used to looking after me.”[10]

Chris O’ Neal also described his eerie memories of the suicide rehearsals in Jonestown:

“We voted to see who would be willing to die. … I thought it was just a scare.”[11]

Similarly, the media was attracted to the story of elderly survivor Hyacinth Thrash, who had slept through the deaths in her cottage. Even while bedridden and frail in her hotel room, Thrash hesitantly described waking to find everyone in the camp dead to a crowd of eager reporters:

“Not a living soul was in view. I struggled along the path to the pavilion and was surprised no one was around. I was looking for the senior citizens center and I managed to pull myself up the stairs. It was then that I saw all my people.”[12]

Finally, some survivors, like Odell Rhodes, found their only solace in alcohol:

“I can’t sleep. I tried sleeping one night without alcohol and I had nightmares,” said one, Odell Rhodes.[13]

*****

Although anxiety and uncertainty was already high, the Park Hotel “living drama”[14] – as the media deemed it – intensified with the arrival on Saturday, November 25, of the Carter brothers and Mike Prokes at the hotel. It had only been a week, and the addition of the trio – all perceived as loyalists to Jim Jones – sparked frightened reactions from those who had left with the congressmen or had refused to take the poison in Jonestown. Some went so far as to openly accuse them of acting as hitmen for the Temple. One – Stanley Clayton – reportedly needed “to be restrained from jumping off the third-floor balcony”[15] after learning of the trio’s arrival.

Most notable, however, was the reaction of the Parks family towards the three, whose anger culminated in an intense confrontation between Dale Parks and Mike Prokes the first evening. The two were described as having shuffled into a cramped phone booth together as they both desperately attempted to convince the U.S. Embassy to find a different hotel for the three.[16] Yet, in spite of their desperation, the Embassy did not heed their request, and the trio ultimately remained at the hotel. What was worse for them was that, because a football team from the Soviet Union was in Georgetown for a game, all rooms at the Park Hotel were occupied, and the three new arrivals were forced to sleep on the hotel veranda, leaving them exposed to the media.

Buffeted by ninety degree heat and the noise of a local Guyanese steel-drum band,[17] the Carter brothers and Mike Prokes repeatedly fought through their exhaustion to proclaim their innocence. The three insisted that they, too, shared the same incessant anxiety and fear as the other survivors. Still, despite their repeated assertions, they continued to be ignored – if they were lucky – by the defectors. In an interview a week later, Tim Carter explained the tension between them and some of the other survivors:

“We understood their paranoia and I don’t think they understood [ours]. They didn’t know the circumstances surrounding our – believing our – I mean it was an understandable reaction I think on their part and I think they came to realize we were as afraid of them as they were of us.”[18]

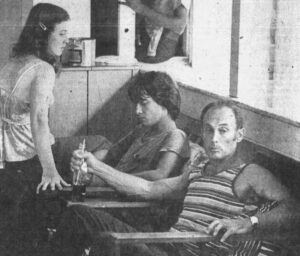

Witnessing the reactions of survivors towards the trio, the media abruptly turned their attention towards the Carter brothers and Mike Prokes for what became, as Tim Carter, later referred to it, “interviews for twenty-eight hours straight.”[19] As the three took seats at a table on the veranda, reporters quickly hurried over to them. They first asked – begged – to be left alone, then warily agreed to talk. Wielding bright lights and tape recorders, reporters pummeled them with questions. Similar to the interviews of the Parks family and other survivors, reporters demanded to know details of their survival, especially given the circumstances of their seemingly bizarre escape with suitcases of money. Sitting nearby, Jonestown defector Harold Cordell overheard their interview and abruptly interrupted, accusing them angrily of being “goddamn liars.”[20]

A Rolling Stones journalist later described the dilemma of their situation:

They were constantly checking the position of the Guyanese soldiers, and, I imagined, looking for an escape route. They feared the dissenting survivors and felt they might be killed because of the nature of their escape and their leadership positions. They refused to go to their rooms on the third floor. Escape routes there were limited.[21]

Mike Carter would later recall the stressful circumstances of their forbidding situation:

“We had lost control of privacy. We had been isolated for a week from other people, and then we were thrown into a holding cell to being put in the middle of a hotel lobby where they couldn’t put us into a room. And reporters are dying for new information.”[22]

*****

The group of survivors from the Northwest District at the Park Hotel were soon joined by a new outsider. Characterizing himself as a cult expert and psychiatrist, Dr. Hardat Sukhdeo had flown from New Jersey to his native country to counsel and interview survivors. During his ten-day stay, Dr. Sukhdeo personally met with and interviewed over forty survivors, many of whom were at the Park Hotel.[23] The ultimate impact of Dr. Sukhdeo’s counseling remains vague, yet he showed particular concern for survivors like Mike Prokes, Stanley Clayton, and Odell Rhodes, as shown in his reaction to Rhodes’ manifestation of extreme anxiety:

Rhodes, a crafts teacher at Jonestown, collapsed at his hotel Saturday night and had to be taken to a hospital. “Mr. Rhodes is under severe pressure and he felt that he was being pulled by all sides,” Sukhdeo said. “He was being offered a lot of money to do stories. He was being offered jobs in the United States and he must have been hard put to make a decision of what he really wants to do. I would feel that part of this is a severe anxiety reaction that caused his collapse.”[24]

Like the media, Dr. Sukhdeo was driven to excess in the frenzical climate of the Park Hotel. Based upon his observations in his interviews with survivors, Dr. Sukhdeo adamantly insisted in later interviews with the FBI and press that they had been brainwashed and thus needed to be deprogrammed. The result was that Dr. Sukhdeo’s comments served to fuel the long-standing perception that survivors were little but feeble-minded cultists.

*****

When the military completed its task of removing the 900 bodies from Jonestown, selected members of the press were allowed to visit the now-uninhabited site. Most of their attention turned towards the ghost town-like remains of the community, although some reporters continued with their focus on survivors. The Carter brothers and Mike Prokes, remaining of primary interest even after 25 hours of living on the hotel veranda, finally secured a hotel room. Still, this did little to deter the press, who noted their wearied states after hours of further police questioning and interviews:

They were in that room Monday night – sprawled on the bed stripped down to their undershorts in the heat of the tropical night – still talking, still trying to understand what had happened to their vision of Utopia. All three were tired, Tim Carter – who fell asleep during the interview – especially so.[25]

In the meantime, the survivors began to raise their voices on their most important priority: their return to the United States. At first, many of them believed that their stay at the Park Hotel would be short, and that they would soon be granted clearance to depart Guyana.[26] Instead, they faced the challenge of dealing with poor communication and contradictory updates from both the American Embassy and Guyanese officials. After all, a number of the remaining 40 Temple members who had been at the Lamaha Gardens headquarters on the night of the tragedy had already been given clearance to leave or – in fact – had already departed Guyana. On December 11, nearly four weeks after the deaths, Gerald Parks expressed his frustration in an interview with The Los Angeles Times:

“They have no legal right to hold us here. It is against their [the Guyanese] constitution and our [U.S.] law.”[27]

Ten days later, shortly before departing Guyana, Dale Parks described their trouble dealing with the U.S. Embassy to The Washington Post:

According to Parks, the defectors have been trying for three weeks to arrange through the embassy for transportation out of Guyana. … The U.S. consular officials told them at one point that the embassy could not give them their passports because they had not been cleared for release by Guyanese Officials.[28]

In retrospect, Mike Carter expressed his dissatisfaction with the State Department’s handling of their situations:

“I don’t know what the State Department was thinking. It just goes to show how little communication and coordination was going on between the U.S. Government and the local authorities as well. It was just a mess. … I never got the impression that any of the survivors were anything but a pain in the ass for them – ‘Oh this was a problem we had to deal with.’”[29]

*****

As the post-tragedy hysteria at the Park Hotel began to ease, the original tension between the groups of survivors mostly subsided. They found themselves at greater liberty to roam the streets of Georgetown and to stop by Lamaha Gardens.[30] The anxiety that some of the survivors had towards each other began to ease. Responding to an incident where Brenda and Edith Parks expressed concern about the presence of the Carter brothers and Mike Prokes, Gerald Parks said:

“Oh, will all of you calm down? We’re in a hotel here, there’s two guards with us, there are people all around. Use your head – if anybody was going to kill us here, they would have already killed us!”[31]

Following their visit to Jonestown, most of the press departed, and the atmosphere at the Park Hotel quietened. About half of the original Eve Leary group remained there, as it became apparent why they were still being held: they were to be called to testify either at the Guyana Inquest or at the preliminary hearing of Larry Layton’s trial (or both).

Both courts commenced on December 13, nearly a month following the tragedy. Layton’s preliminary hearing was to determine whether or not a jury would be empaneled for his trial. Over the span of three weeks, Monica Bagby, Juanita Bogue, Harold Cordell, Dale and Gerald Parks – all of whom had survived the airstrip shootings – testified as witnesses. They spoke of Layton’s devout loyalty to Jim Jones, and how it demonstrated itself at the airstrip. As Juanita Bogue testified:

“He [Joe Wilson] was shaking Larry Layton’s hand and as he shook hands I could see him pass a small black object underneath his poncho.”[32]

The preliminary hearing on Layton’s role concluded in early January 1979 with a decision that he would be held over for a jury trial on multiple charges. At the same time, the Guyana Inquest investigated whether the deaths in Jonestown were suicides or murders directed by Jim Jones. Through the course of ten days in a tiny court in Matthews Ridge – about 28 miles from Jonestown – a five-member Guyanese jury heard survivor testimonies from Tim and Mike Carter, Stanley Clayton, Herbert Newell, Mike Prokes, and Odell Rhodes, who had all flown in from Georgetown to testify. With the exception of Herbert Newell, all five men were present in Jonestown at some point as the deaths occurred. Due to the remoteness of Matthews Ridge, the Guyana Inquest garnered considerably less media coverage than Layton’s preliminary hearing. Nevertheless, since the Inquest heard the detailed testimonies of numerous survivors, it produced some of the most comprehensive early first-hand accounts to exist from survivors.[33]

*****

As press coverage of the aftermath dwindled and most survivors returned to the United States, it seemed that the Park Hotel saga was coming to a definite end. With the conclusion of Larry Layton’s preliminary hearing and the Guyana Inquest, there was no reason to continue to hold the remaining survivors in Guyana. Tim Carter had anticipated that charges would be brought against them – as he considered himself, his brother, and Mike Prokes to be “the most convenient fellows to charge,”[34] – none of the three were, and they departed Guyana in late December. By the end of the year, nearly all of the 87 surviving Peoples Temple members in Guyana had been granted clearance to return home, and the vast majority of them – especially those at the Park Hotel – chose to return to the United States on the next available flight. There were notable exceptions: Larry Layton, of course; Charles Beikman, who had been arrested for his role in the deaths of Sharon Amos and her three children in a Lamaha Gardens bathroom, was in police custody; and so was Stephan Jones, who had blurted from the witness stand during a court proceeding that he was responsible for those deaths. Stanley Clayton was likely the last of the Eve Leary/Park Hotel group to leave. Despite being given clearance in mid-December to return to the United States, he chose not to until mid-January 1979.

Still, the actual process of departing Guyana came with its own set of hurdles. As rumors persisted of survivors acting as hitmen, airlines required most of the returning survivors to be accompanied by a federal sky marshal. In one incident, when 30 survivors were set to depart on a Pan Am flight, the pilot “refused to fly 17 male members of the sect out of Guyana without an FBI escort,”[35] delaying their return by several days. Although American and airline officials were adamant about the presence of sky marshals on returning flights with survivors, this dictum was ultimately loosely enforced. Mike Prokes, for example, managed to leave Guyana on Pan Am without notifying U.S. or Pan Am officials, causing a stir with the State Department.[36]

Nevertheless, upon arriving back in the United States, survivors were greeted by FBI agents, who subjected them to hours of their own interrogation. It was their first step to beginning their new and forever changed lives in their native country.

*****

After operating for nearly two centuries, the Park Hotel met its end in a devastating fire in 2000 and was never rebuilt.[37] Even if the physical remnants of the hotel remain charred, its role in the Jonestown aftermath lingers. The media chose to perceive survivors as cast members in an imagined drama and pit them against one another. Yet, a closer look at the events that took place at the Park Hotel reveals that, regardless of the differences in their situations, they were all just learning to navigate their own struggles in a tragedy unlike any that the world has seen.

Notes

[1] Cable 3847, from Georgetown to State, Nov 21 1978, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=95568.

[2] Cable 3853, from Georgetown to State, Nov 22 1978, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=95596.

[3] RYMUR Serial 72, from Georgetown to State, Nov 23 1978, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=79844.

[4] Francis Quamina Farrier, “Jubilee Main Street, Georgetown,” Guyanese Online, July 16, 2016, https://guyaneseonline.net/2016/07/16/jubilee-main-street-georgetown-by-francis-quamina-farrier-photos/.

[5] John Keasler, “Torpor of Death Surrounds Survivors of Jonestown,” The Miami News, December 7, 1978,https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-miami-news/127341730/ and https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-miami-news/132430548/.

[6] The list of all the survivors who were believed to have stayed at the Park Hotel is available here.

[7] Keasler.

[8] Dan Sullivan and Phillip Zimbardo, “Jonestown Survivors Tell Their Story,” The Los Angeles Times, March 9, 1979,https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-los-angeles-times/131478686/.

[9] Joseph B Treaster, “Special Privileges Aided Older Members’ Survival,” The New York Times, November 30, 1978, https://www.nytimes.com/1978/11/30/archives/special-privileges-aided-older-members-survival-slept-through-the.html?searchResultPosition=70.

[10] Associated Press, “Family Close To Escaping,” The Olympian , November 24, 1978, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-olympian/132434833/.

[11] Jim Willse, “Survivor Vainly Cautioned Ryan About Fake Defector,” The San Francisco Examiner, November 24, 1978,https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-san-francisco-examiner/128076039/.

[12] Peter Arnett, “She Awoke to Find Everyone Dead,” The San Francisco Examiner, November 24, 1978, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-san-francisco-examiner/131590681/.

[13] Willse, “Survivor.”

[14] UPI, “Grisly Job over, Troops Head Home,” The Modesto Bee, November 27, 1978, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-modesto-bee/132435638/.

[15] Eric Brazil, “Survivors Fear Carters, Prokes Still Carry out Jones’ Orders,” The Idaho Statesman, November 26, 1978,https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-idaho-statesman/130705182/.

[16] Jim Willse, “Release Brings Clash with Other Cult Survivors,” The San Francisco Examiner, November 26, 1978,https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-san-francisco-examiner/127400614/.

[17] Tony Russomanno, “Guyana: How It Was,” Nov 25 1978, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=29011.

[18] ABC News: Jonestown Interview with Mike and Tim Carter, Dec 1 1978, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=123607.

[19] Tim Carter, “Presentation at the Griot Institute,” YouTube, (speech, March 20, 2013), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0KLy8TumagE&pp=ygUuR3Jpb3QgSW5zdGl0dXRlLCBGZWJydWFyeSA2LCAyMDEzIC0gVGltIENhcnRlcg%3D%3D.

[20] ABC News Interview: Jonestown Interview with Mike and Tim Carter, Nov 25 1978, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=123600.

[21] Tim Cahill, “In the Valley of the Shadow of Death: Guyana After the Jonestown Massacre,” Rolling Stones, January 25, 1979, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/in-the-valley-of-the-shadow-of-death-guyana-after-the-jonestown-massacre-242259/.

[22] Mike Carter, video call with author, September, 19, 2023.

[23] RYMUR Serial 1690, from Special Agent to FBI, Jan 15 1979, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=78848.

[24] George Esper, “Cult Horrors Haunt Survivors,” The Times Leader, December 4, 1978, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-times-leader/131180329/.

[25] Robert J. Bazemore, “Cult Survivors Begin Looking to Fresh Start,” The Modesto Bee, November 28, 1978, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-modesto-bee/130657623/.

[26] RYMUR Serial 72, from Georgetown to State, Nov 23 1978, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=79844.

[27] David F. Belnap, “4 Claim Guyana Holds Them Illegally,” The Los Angeles Times, December 11, 1978, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-los-angeles-times/128538862/.

[28] Gregory Rose, “Cult Defectors Trying to Leave Guyana Criticize U.S.,” The Washington Post, December 21, 1978, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1978/12/21/cult-defectors-trying-to-leave-guyana-criticize-us/baa59e7e-50a5-497e-ab67-3a56c62a3a4f/.

[29] Mike Carter, video call with author, September 19, 2023.

[30] Cable 3847, from Georgetown to State, Nov 21 1978, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=95568.

[31] Keasler.

[32] John Jacobs, “Ryan Murder: Woman Is Key to Conviction ,” The San Francisco Examiner, December 21, 1978, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-san-francisco-examiner/131535592/.

[34] Robert J. Bazemore, “Jones Was Anti-Suicide – Prokes,” The Modesto Bee, November 30, 1978, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-modesto-bee/130706550/.

[35] Peter H. King, “Pilot Refuses to Let Male Temple Members Aboard,” The San Francisco Examiner, December 4, 1978,https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-san-francisco-examiner/128366294/.

[36] Cable 4458, from Georgetown to State, Dec 27 1978, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=95568.

[37] Gwen Evelyn, “Fire Destroys Park Hotel, New Thriving Restaurant,” Guyana Chronicle, May 7, 2000, https://www.landofsixpeoples.com/news/nc00507.htm.