(This blogpost by Kelly Lavoie was originally published on January 3, 2020, and is reprinted with permission.)

A Single Tree in a Forest

I think that most of us who research Peoples Temple can’t help but make comparisons, noting the parallels between their 1970’s world and our 2020’s world. Often, it’s a cautionary tale about the dangers of losing too much of yourself in a charismatic leader – a highly salient point when it comes to current politics more than any current threat of “cults” as they are typically understood, if you ask me.

Naturally, we have the urge to “categorize” the people of Peoples Temple. To bring order into the picture, in an attempt to comprehend a confluence of factors so tangled and a tragedy so viscerally affecting that it defies understanding.

Dr. Mary McCormick Maaga breaks the congregation of Peoples Temple down into three categories in her book, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown (1998), from which this chapter was reprinted:

By looking at the three groups that existed side by side within Peoples Temple and exploring the motives for each one gains an insight into the complex nature of the decision to commit suicide on 18 November 1978. I argue that a membership shift occurred when Peoples Temple relocated to California, which caused Peoples Temple to become first two, then later three, groups within a single movement. The Indiana Peoples Temple was essentially a sect, which was joined by new religious movement members in California, which then recruited black church members as it focused its ministry on the residents of urban California.

The idea of the three groups is not an exhaustive way to define the people of Peoples Temple. That is more an observation than a criticism, since the nature of what Dr. Maaga was doing here was “panning back” and generalizing for the sake of broad analysis. A general summation.

There were some black members who followed Peoples Temple to California from Indiana, as well as others from various states across America (Moore,2017), not just from urban San Francisco or Los Angeles. There were some black members who were motivated by progressive political beliefs. There were some black members who were financially doing just fine, such as Christine Miller (Bellefountaine, 2013) or Bea Orsot (Orsot, 1989). There were some black members (but, importantly, not all) who were helped by the church with various personal problems – as were some white members, such as Dr. Larry Schacht, who struggled with addiction at the time he joined (Crutchfield, 2013).

The problem with “summing up” a group so large and diverse is that mischaracterization is almost inevitable. I’m not suggesting that there is no value to the sort of thought and study that individuals such as Dr. Maaga have brought to the table in their work. But I am suggesting that something very important is missing from the discourse if generalized views are the only ones considered. And that is the most popular approach to the story of Peoples Temple. Not only does this aid in academic study; it helps to compress certain details into cohesive plot-lines for documentaries and the like.

What is missing from the popular narrative is personalization – not superficial, trope-driven personalization, but efforts to deeply understand Peoples Temple members as real people, individually, to whatever extent is possible. Truly getting acquainted with the fact that these were human beings just like you and I. No more, no less. Even Jim Jones was a human being. People like to separate themselves from people like him to the extent that they see him as a monster, but monsters aren’t real. Human beings sometimes do horrible things.

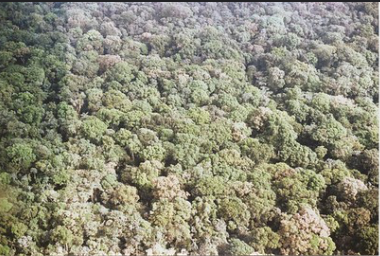

For my purposes, looking into one person at a time is a more effective approach than categorizing people into groups. In doing so, elusive dimensions reveal themselves, adding to my understanding of the greater whole. Like visiting a tree up close – say, one of those trees out in the Guyanese jungle – I’m then able to remember the details even when I view the whole forest from above. From then on, the way I see the forest is changed.

For my purposes, looking into one person at a time is a more effective approach than categorizing people into groups. In doing so, elusive dimensions reveal themselves, adding to my understanding of the greater whole. Like visiting a tree up close – say, one of those trees out in the Guyanese jungle – I’m then able to remember the details even when I view the whole forest from above. From then on, the way I see the forest is changed.

Not So Different

A realization that unfolded as I researched a specific person: fundamentally, I am not so different than he was. That person was Richard Tropp. The suspected (but impossible to one-hundred percent confirm) author of the Anonymous Letter, the unsigned note found at Jonestown, where all but two souls had passed on.

If you’ve read my past articles on Jonestown, you know that this letter, at first, pissed me right off. I could not stomach what I viewed as a blatant attempt to influence our collective view of what happened in a false light, to portray the travesty that must have unfolded before him as a voluntary, revolutionary act. And the more I came to view the majority of the deaths as murder, the more Tropp’s attempt at deception pissed me off.

I don’t see it quite the same way anymore, though. I don’t think he wanted to fool me. I think he wanted to fool himself. And guess what – I’ve been known to try to fool myself on more than one occasion in my life. Tropp wanted to believe the ideals he’d started with were under attack from without, rather than to face the problems that killed them from within.

Based on witness accounts, he argued vociferously against the death option shortly before the end. To my mind, his protestations indicate that, regardless of what he may have written in that letter, he knew the truth at that moment. Tropp also authored a memo to Jim Jones, around six months before the end, one which I briefly discussed in a prior post. Here is an excerpt from that memo:

… I think it is significant that the first thing that was mentioned in yesterday’s meeting was immediate dismantling of the “boxes” or isolation units… As you said at the end of the meeting, we need to function on a “day by day” basis. While this is true, I think that without a sense of a possible future, it’s going to be hard to build in the necessary motivation for achieveing [achieving] production goals for the community…I strongly suggest that, while continuing to function on a “day-to-day” basis, our community begin to implement some short and long range production planning, of the sort that the Soviets did and which they found to be the key to motivation and building community initiative… begin to make 6-month, one-year, two-year and 5-year plans… As we do this, as we QUANTIFY the production goals, we can build into the community a desire to MEET THE GOALS, to work hard for them. We can set in motion CAMPAIGNS to meet certain goals, campaigns that can at times MOBILIZE the whole community on special assignments… it will provide a kind of psychological balance for the effect of white nights on the kids – they will develop the determination to sacrifice for the collective, but also have the accompanying sense that we are building something, and not just going from one day to the next…

Here, Tropp was clearly making a case for decreasing abusive punishment tactics and setting goals for the future, demonstrating a clear desire to 1.) live, and 2.) make the settlement successful. This was a man who deeply desired his vision of Peoples Temple to have been real – a bastion of equity, a model for future communities. In a dramatic reading penned by Tropp, his view of Jonestown is elaborated vividly:

To our foster mother America, we say: we are an attempt to rediscover you, the “America” that never lived up to its promises and ideals of liberty and justice for all, and has finally given up… America, we were your children… but you didn’t want us to be born. So we have come here, and will continue to come. We will not curse you, but be an ironic vindication of what you’ve betrayed in the name of the highest human ideals and aspirations. We will reclaim freedom’s birthright. We will discover America in spite of you.

He wanted the settlement to succeed because he believed in the rightness of the endeavor – or what the endeavor purported itself to be. And, make no mistake, Jonestown wasn’t what it purported itself to be, because many of its residents were suffering.

The messaging was not consistent – while Tropp clearly wanted to believe – “We will not curse you, but be an ironic vindication of what you’ve betrayed” – that their group’s main aim was a successful and thriving communal settlement rather than hostility toward other entities, witness accounts and recovered evidence suggest that not everyone favored the “live and let live” philosophy.

Notorious audio segments of residents describing how they’d like to torture their relatives or anyone they perceived as the Temple’s enemies, along with some of the “Dear Dad” letters – notes from members that would be given to Jim Jones – offering to suicide bomb, self-immolate, kidnap, and “get” specific “enemies,” thrust this dissonance of understanding into sharp relief.

I’d like to mention that I believe most of those notes and audio to be a big show meant to impress Jim rather than sincere – and that is not a slight, since “impressing” Jim could be directly related to your well being at Jonestown.

But the fact that members felt the need to impress him by offering to attack their enemies demonstrates the unfocused nature of what Jonestown’s goals really were. There were those following Jim’s lead, seemingly unable to let go of the idea that they were being attacked and must fight fight fight. Jim orchestrated that mentality as best he could, in fact, staging attacks and lying about conditions in the United States.

Then there were people like Tropp, whose primary goal was to make the town a success… and I do believe that most of the people who were there willingly were of that mindset.

Tropp’s ideals in life were a whole hell of a lot like the ones held by many of we liberal Millennials and Gen-Z (some of you Gen-Xers too, and the occasional Boomer… can’t forget ya’ll). The following is excerpted from an untitled manuscript penned by Tropp, one which appears to be the beginnings of a biography of Jim Jones. It illustrates how Tropp viewed Peoples Temple, Jim Jones, and their aims:

Throughout his ministry, Jim Jones has used his pulpit to deliver blistering attacks on the abuses and corruption of American institutions and the forces of American capitalism as wielded by the ‘power elite.’… He has inveighed heavily against the military-industrial complex, corporate rip-offs, corruption of all sorts, war profiteering, the politics of neglect and genocide, treatment of American Indians, blacks, welfare mothers, the elderly, a host of other issues. He has reserved his most pungent and devastating attacks for the ruling elite that runs the economy, and dehumanized millions of people in its profit machines. Jim Jones is a foe of the ‘affluent society.’ He has verbally attacked the ‘masters of war’ who rob ordinary people of decent health care, housing, schools, safe working conditions, and adequate social services, in a massive conspiracy with politicians to build frightful arsenals of mass destruction that threaten the world. He has charged neglect of safety standards in America’s factories, fields, and mines, and condemned the laissez-faire attitude of government toward organized crime and dope-dealing. He has waged a comprehensive attack upon the superficial, commercialistic TV culture… He has scored the failure of the educational system, police brutality, crime in the ‘suites,’ corruption in the treatment of children, the elderly, and the mentally ill, exposing the massive inequities that characterize every area of American society.

Tropp, Unpublished Manuscript

If you read that and found yourself thinking, “Only a sycophantic cult member would speak so highly of Jim Jones!” I’d ask that you consider a couple of factors.

First, the deaths had not happened yet, and were a long way off at this point. Our view of the people involved is strongly shaped by knowing how things would ultimately end – Tropp, when he wrote this, did not.

Second, suspending character judgments for a moment – note the fact that every social problem he noted is still very much at the fore of American consciousness. Just as salient today as they were back then; economic inequality, commercialism, racism, worker’s rights, police brutality, health care, militarism, and the vulnerability of populations such as children, the elderly, and the mentally ill.

“…deliver blistering attacks…”

“inveighed heavily against…”

“…his most pungent and devastating attacks…”

“…is a foe…”

“He has verbally attacked…”

“He has waged a comprehensive attack…”

“He has scored the failure…”Tropp, Unpublished Manuscript

This approach, the approach of being embattled against an evil enemy, was deeply pervasive in Peoples Temple. It’s plainly apparent in the accounts of survivors, as well as letters, memos, and audio left behind, such as the “Dear Dad” notes. I believe this embrace of the notion of fighting, of vanquishingenemies, was one of many factors that led up to the tragedy at Jonestown.

Retribution vs. Restoration

The embattled tone of Tropp’s diatribe against social injustice in the untitled manuscript is essentially no different from what I see all over the internet, every day. It’s not that different from the things that I feel when I see flagrant injustice. The urge to fight back, to wear my anger and indignation like battle regalia and use it to hurt my “enemy,” is potent.

How can I, occupying my position of relative privilege in this world, tell others not to fight back against injustice?

I can’t. Or, rather, I won’t.

I’m not making the claim that everyone ought to approach social justice uniformly. I think that what’s right for me may not be for someone else, and that is just fine. I’m not interested in dictating to other people how they ought to view or interact with the world.

What I am interested in is lifting up the idea that dialogue is not a bad thing, unconditional compassion is not a bad thing, leaving doors open is not a bad thing. Because it is missing in the vast majority of public sentiment. In our current environment, dialogue with and compassion for “the enemy,” whoever that enemy may be, is nearly taboo.

I’ve learned a lot of things from studying Peoples Temple. One specific thing that I have learned from studying Tropp, I see as the root of where he and others like him went awry: If the rhetoric of battle is the most prominentrhetoric in public discourse, I should not be surprised that the social problems of the 1970’s remain problems in 2020.

What’s the difference between a frightening extremist and a heroic freedom fighter? It doesn’t make much sense to me to say, “the use of violence against the innocent” (which, I think, would be the answer that many would give to that question). For many reasons, ones that orbit around the fact that the concept of “innocence” is a subjective, fluid based on social and cultural factors (yes, even when it comes to children – I wonder how many “war heroes” have directly or indirectly had a hand in killing children? But that’s a whole other can of worms).

I don’t think I should be so quick to delineate myself from my “enemies” when all of my words and sentiments up to the precipice of violence are near identical.

I’m not talking about disagreement, debate, or speaking my mind on issues. I’m talking about believing that human beings are “trash,” “worthless,” “cancelled,” “monsters.” If you spend any time at all on social media of any kind, I know you know there are way worse words and statements than that, too.

Near the end, Tropp could see it too. In a memo to Jim written not long before the deaths, Tropp puts forth ideas that he felt would make Congressman Leo Ryan’s potential visit a success. Here’s one of them:

Our aim should not be merely to present a Clean and Neat Jonestown, and defend against the lies, but to EDUCATE this Congressman, to open his eyes to what we are doing here.

Destroying my “opponent” does not address the root of injustice. It doesn’t move us forward as a society of human beings.

I know that there are things that have been and might be improved through conflict – many laws that protect the innocent and restore basic rights to various populations (People of Color, Women, etc.) were undoubtedly foughtfor, physically and verbally.

But we’re still blighted by racism, and sexism. While conflict can serve invaluable functions, it will never address the deeper sickness that brought about the injustice in the first place. Dialogue does. Compassion does. This is how true social justice becomes possible.

References

Bellefountaine, M. (2013) “Christine Miller: A Voice of Independence.”

Crutchfield, L.H.L. (2013) “We Loved Each Other When We Were Young.”

“Letters to Dad” FBI documents RYMUR 89-4286-N-1-A, RYMUR 89-4286-EE-1-AB.

Maaga, M. (1998) “Three Groups in One.” Originally in Hearing the Voices of Jonestown, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1998.

Moore, R. (2017) “The Demographics of Jonestown.”

Orsot, B. A. (1989) “Together We Stood, Divided We Fell.” Originally in The Need for A Second Look at Jonestown by Rebecca Moore & Fielding McGehee III, Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1989.

Tropp, R. (1978) “Memo from Dick Tropp, May 1978.”

“Richard Tropp’s Last Letter” (1978) FBI document RYMUR 89-4286-X-1-a-54.

Tropp, R. (N.D.) “Who are the People of Jonestown?” FBI document 89-4286-EE-1-T-57 – EE-1-T-63.

Tropp, R. (N.D.) “Untitled.” Unpublished Manuscript.

Tropp, R. (1978) “Richard Tropp Memo on Ryan Visit to Jonestown” FBI document RYMUR 89-4286-AA-1-x-1.