CASSIUS.

But what of Cicero? Shall we sound him?

I think he will stand very strong with us.METELLUS.

O, let us have him! for his silver hairs

Will purchase us a good opinion,

And buy men’s voices to commend our deeds:

It shall be said, his judgment ruled our hands;

Our youths and wildness shall no whit appear,

But all be buried in his gravity.

–Julius Caesar (Act 2, Scene 1), in which the conspirators who want to murder Caesar discuss how having a wise old member of the Roman Senate, Cicero, will support their movement, and they shall then be able to gain legitimacy in the eyes of the people.

* * *

“The reactionary suicide is ‘wise,’ and the revolutionary suicide is a ‘fool,’ a fool for the revolution in the way Paul meant when he spoke of being a ‘fool for Christ,’ That foolishness can move mountains of oppression; it is our great leap and our commitment to the dead and the unborn.”

– Huey P. Newton, I Am We, or Revolutionary Suicide

* * *

November 18, 2008, marks the thirtieth anniversary of the tragedy at Jonestown in which 918 people lost their lives. Among those who died that day were Jim Jones and 909 of his followers in Jonestown, Guyana (as well as four individuals who died at the Peoples Temple headquarters in Georgetown, Guyana). As Jones, leader of Peoples Temple, called for his followers to commit mass suicide, he recorded the proceedings. This final tape, labeled Q042 by the FBI, is more commonly known as the “death tape.”

Earlier this year – but not for the first time – I read the transcript of that final tape, and I was struck by how many times Jones calls upon his followers to commit what he termed “revolutionary suicide.”

“Revolutionary Suicide.” What is it? If it wasn’t Jones’ own term – and it isn’t – where did the term come from, and what was its original meaning? Perhaps most importantly, what did Jones mean when he used the term?

In my research, I discovered that this term was coined by Huey P. Newton, another man who was seen as a “revolutionary” by his supporters. And no matter what Newton meant when he used it, I also found that Jim Jones had greatly twisted the meaning of this concept in order to better fit what Jones himself wanted.

In this paper, I will discuss how Huey P. Newton coined the phrase, how Jim Jones defined it – and changed its definition over the years, and whether what happened at Jonestown on that final day should be considered a Revolutionary Suicide in any interpretation of Newton’s definition.

The late 1960’s and early 1970’s : Social Change

Let me begin by setting the backdrop for the time, as well as the history of Huey P. Newton, Jim Jones and Peoples Temple. The late 1960’s and the early 1970’s were a time of great social upheaval in the Unites States. American troops were being sent to Vietnam to fight the threat of Communism spreading from the northern part of the country to the South. Many individuals in the United States felt that this was an unjust war, and their sentiments were merely strengthened by the images on their television showing the brutality and pointlessness of war. As the situation in Vietnam dragged on, people began to demonstrate against the aggression of the U.S. in what was basically a civil war amongst the Vietnamese.

Other movements also affected the landscape of society in this time period. The women’s movement pushed for the rights of American women in the workplace and the home, as well as challenging long-held stereotypes of women. A sexual revolution was also taking place, in which men and women began to be more verbally open about sex. Taboos were broken, books were published to educate the common man and woman about sex and how best to enjoy it in a way that the “sex ed” classes of the time had never discussed. Finally, and perhaps most importantly for this discussion, the Black Power movement sought to right the social inadequacies that African-Americans had to deal with on a daily basis. Individuals and organizations pushed for better housing, education and employment for African-Americans; they called for the African-American communities to rise up and claim what was believed to be rightfully theirs from the white majority who had oppressed them for so long.

It was in this climate of immense change that Jim Jones and Peoples Temple came to prominence.

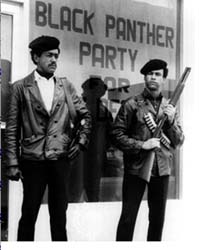

At the same time, a Black Power movement emerged in the ghettos of California, dedicated to the idea that the African-American community should take back their neighborhoods. Co-founded and led by Huey Newton, the Black Panther Party grew from Oakland’s inner-city and spread across the country in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s.

In order to understand how Newton came to articulate the concept of “Revolutionary Suicide,” then, we must first understand where he was coming from, both physically and psychologically.

Huey P. Newton and the Black Panther Party

Huey Newton was a young African-American who had grown up in the ghettos and slums of inner-city Oakland, California. He was a self-made man in many ways. When he graduated from Oakland Technical High School, he was barely literate. He taught himself to read by slowly and painfully poring over poetry and books. One such book was The Republic, which – according to Newton – he had to read over five times before he understood what Plato was talking about. Newton became a voracious reader, devouring books written by revolutionary figures such as Marx, Lenin, Mao Zedong, Malcolm X and Che Guevara. Continuing with his education, Newton enrolled at Oakland City College and became active in groups that promoted African-American pride and independence from the oppression of the United States. There he met a fellow African-American student named Bobby Seale, and together, they formed the Black Panther Party, dedicated to helping the oppressed African-American communities that the two men were all too familiar with. Bobby Seale became the party Chairman, while Newton was the Minister of Defense.

Along the way, Newton began to articulate his revolutionary concepts on what he believed the ravaged African-American communities deserved. His “Ten Point Plan” enumerated which the Black Panther leader felt that the communities needed to have in order to be functional and free of the oppression from what he called the “decadence of American Society” (https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/primary-documents-african-american-history/black-panther-party-ten-point-program-1966/).

Newton was very intelligent and understood the laws of California. Knowing that it was legal to carry a gun in California as long as it was registered with the state, he encouraged African-Americans to do so and to go out on patrol at night in their own areas. The purpose of these patrols was to monitor the actions of the local police and to thwart any attempts by the authorities to mistreat African-Americans in the community. Due to the patrols and other such actions, the Black Panther Party – and Newton himself – quickly gained national notoriety.

As he worked along with Bobby Seale and other Black Panthers, Newton also articulated his concept of “Revolutionary Suicide.” For him, “Revolutionary Suicide” referred to the need for African-American people to stand up – even at the risk of their own lives – to fight against the oppression of racism and poverty, as well as the agents of that oppression, the police and the government. The action was revolutionary because of what they fought for, and suicidal because confrontations with the police and government would expose the revolutionary to almost certain physical injury or death. Newton also stressed that the work of the individual to fight oppression should advance the entire cause. In other words, according to Newton, those who engage in “Revolutionary Suicide” should not – and do not – desire to die by their own hand; instead, the “Revolutionary Suicide” engages in acts which might lead to his death at the hands of his oppressors. Above all, Newton believed that in teaching the young to continue after the elders die in the struggle, the elders would achieve a sort of immortality that could not be found by simply killing one’s self for the cause.

To contrast his concept of “Revolutionary Suicide,” Newton also defined “Reactionary Suicide” as “a hopelessness, demoralization and the acceptance of the oppression of blacks” by blacks themselves. This can be extrapolated to mean a sort of defeatism, a belief that one does not act, but is instead acted upon by external forces, e.g., the oppressors.

Jim Jones and Rhetoric

Jim Jones and other members of Peoples Temple had a history of taking the rhetoric of others and using it for their own purposes. Newton had great credibility and legitimacy in the African-American community, making him, and the Black Panther Party, the best entities for Jones to borrow ideas from, and to present them – with his own definition, if he chose – to his largely African-American congregation. There are some ways that Newton and Jones were similar, but the contrasts between the two couldn’t be more stark. Like Huey Newton, Jim Jones was influenced by the writings of Mao Zedong, but Jones focused on Mao’s quote that “political power came only through the barrel of a gun.” As audiotapes from Jonestown showed, Jones repeated this phrase to his followers over and over: there is even a Jonestown tape in which Jones quizzes one Peoples Temple members about Mao’s statement. Although he was influenced by Mao, just as Newton was, Jones only took those ideas from Mao that he felt would best fit his cause, he didn’t give any legitimacy to anything that didn’t support his beliefs. The biggest difference between them, though, was that Newton tried to reinforce the idea that he was a normal human being, nothing special; Jones, on the other hand, wanted to be thought of as God-like, and reminded his followers of his similarities to such icons as Jesus and Lenin.

Although Peoples Temple comprised many different races and creeds, the majority of Jones’ followers were African-American. Therefore, it becomes only logical that Jones would assimilate the rhetoric of the Black Panther Party, which had come to dominate the revolutionary landscape for African-Americans in California and other places. Jones heard Newton’s concept of “Revolutionary Suicide” and he latched onto it just as he had Mao’s adage about power. The Temple leader began to bandy the term about as if it were his, and indeed, his definition of what Newton had meant by “Revolutionary Suicide” changed often based upon what Jones wanted to accomplish. The changes in meaning would multiply after Jones and a thousand of his followers migrated to their agricultural project in Jonestown, Guyana.

Jonestown: 1977-1978

Life in Jonestown was hard. The soil conditions were inhospitable to many American crops which they initially planted, and the new emigrants were unfamiliar with some of the native vegetables. In addition – especially with a thousand new residents descending upon the community in a short time – Jonestown struggled for self-sufficiency, and had to import much of its food from the outside during most of its existence. The work under the tropical sun was long and hot, and discouraging to many.

In addition, the Jonestown leadership felt under siege. Social Security checks, which should have been forwarded as a matter of course, were blocked by the U.S. Postal Service. Radio communications with San Francisco and the Temple headquarters in Guyana’s capital city of Georgetown were threatened. Customs agents were seemingly hyper-vigilant in their inspections of cargo destined for Jonestown.

But most of the history of Jonestown’s short existence pivots on the custody battle over one young boy, John Victor Stoen. His mother, Grace Stoen, had left the church after signing documents granting custody to the Temple. Two men claimed paternity for the boy: Jim Jones; and Jones’ top lieutenant and Grace’s husband, Tim Stoen. Grace sued in California for custody of John Victor, and – with the help of her husband who had also defected from the Temple and joined his wife in the battle – obtained a court order restoring custody to her. Jones refused to comply, but felt he could no longer leave the jungle community to which he had fled, for fear of being arrested for the noncompliance.

The delayed checks, the threatened radio license, the inspections of cargo, and especially the court case fueled Jones’ increasing sense of paranoia. But Jones had other, more immediate concerns as well, that his long-suffering and hard-working followers would commit suicide rather than to remain in Jonestown. In late summer 1978, 20-year-old Ricky Johnsonattempted suicide by drinking gasoline. The young man had his stomach pumped and, as Jones noted in two tapes (here and here),”shit fire” for a week, but Jones became terrified that some of his other followers might make similar attempts. He spoke of the selfishness and futility of individual suicide – it would set the suicide’s evolution back “five hundred generations,” he said in one tape – which differentiated it from that of a mass “Revolutionary suicide.” And it was this latter concept which fills many of the Jonestown tapes.

“White Nights” and their Importance to Peoples Temple

One cannot understand Jonestown, or the tapes cited in this article, without first knowing what a “White Night” was to Jones and the members of Peoples Temple. A “White Night” was Jones’ term for a “war-like crisis” in which the community might have to die if they couldn’t prevail against whatever enemy/situation they were facing at that time. While there were a few “White Nights” in California before the mass migration, most did not occur until the last 18 months on Jonestown’s existence. He would invoke the term whenever he felt threatened (physically), or when he felt that Peoples Temple was threatened (that their work would be stymied). During these crises, he and the group at large would often discuss suicide, among other options, if they couldn’t remain as they were, self-governing and intact.

“Revolutionary Suicide” as Mentioned on Tapes from Jonestown

There are ten tapes from Jonestown in which Jones uses the term “Revolutionary Suicide” and gives his definition of Newton’s concept ending, of course, with the so-called “death tape,” Q042.

In tape Q135, recorded in September 1977 during a period which was referred to as the “Six Day Siege,” we see Jones’ first known mention of “Revolutionary Suicide” in Jonestown. The first part of the tape clearly takes place on a boat, during an attempt by a handful of Temple members to flee to Cuba. They are under the impression that they must leave Guyana, because Jones has ordered them to try to do so. The exodus has been sparked by the belief that Guyana is willing to serve a warrant on Jones for John Victor Stoen. Referring to Jonestown, Jones states that “we fought to build it, so we’ll fight to die for it.” Later in the tape, Jones is on the radio, talking to followers in the United States (including his wife, Marceline) and explaining that the GDF and Grace’s attorney, Jeffrey Haas, had entered Jonestown to alert Jones that there was a warrant out for him in the case of John Victor Stoen. Referring to this threat, Jones says, “we do have the right to die and everyone made that decision… we will die unless we are given freedom from harassment and given asylum.” Here, Jones is basically defining “Revolutionary Suicide” as a tactic to use in the political and legal arena in order for Peoples Temple to get its way. This is nothing like what Huey Newton meant when he defined “Revolutionary Suicide”: the revolutionary does not physically hurt himself, or threaten to do so, in order to get his way; rather, it will be the actions of the oppressor that will cause the death of a revolutionary suicide.

In tape Q642, dated February 16, 1978 – coinciding with the date of a “White Night” that is cited in the journal of Jonestown resident Edith Roller – Jones and his followers discuss options that they have should a war erupt and their settlement be invaded. As a group, the residents seem to be torn between staying and fighting for Jonestown, fleeing into the jungle, or committing “Revolutionary Suicide,” as they term it. Jones warns that those who would survive to live without Peoples Temple would be made to lie and would affect the historical impact of the group.

“Suicide is an immoral act,” Jones says. “Only Revolutionary Suicide is justified… Do what Cuffy did, commit suicide. That’s a revolutionary act, rather than be taken prisoner or go back into slavery.” In this case, Jones is mistaken, not only about Revolutionary Suicide, but also about the circumstances of Cuffy’s suicide. The people in Jonestown – as did the people of Guyana – gave great weight to the life of Cuffy, a Guyanese slave who led a rebellion against white slave holders in 1763. In that way, Cuffy was revolutionary. However, when Cuffy’s power to lead and negotiate was taken from him by another slave, Cuffy committed suicide in despair. By definition, therefore, Cuffy’s suicide was not revolutionary in nature at all, but rather – under Newton’s definition – reactionary.

But the more fundamental error is Jones’ statement that “Revolutionary Suicide” of the group would be better than if they were slaves or prisoners: one can only assume that Jones means being a slave/prisoner of capitalism by returning to the United States to live there. For Newton, however, the revolutionary who decides to be a “Revolutionary Suicide” can most certainly expect to be made a prisoner/outcast at some point in his life because he is working outside of the boundaries of “normal” society. But the revolutionary may not end his life through suicide in order to escape this punishment. Instead, he needs to remain strong and centered even while incarcerated.

In Tape Q643 – a continuation of the White Night on tape Q642 – Jones focuses on what would happen if they committed suicide en masse. He is concerned with how the group will be seen historically, another recurring theme in his Jonestown rhetoric. “We gotta think about history,” Jones says. “We are communist. We gotta think about history.” This concern about how any action that they take will be seen by outsiders, especially those in the communist world, characterize many discussions. Even as they parse their options, Sharon Amos speaks up to state her belief that they should threaten mass suicide in order to get what they want, just as they had done during the “Six Day Siege” (tape Q135).

Nevertheless, the majority of Jonestown members who follow Amos to the microphone oppose the idea. They want to fight for their community, their land, their friends. An unidentified woman speaks directly to Jones’ concern about how their movement would be seen by history: “I feel, that if we took a stand… where we all decided to die, that it might never be interpreted correctly in history and that we owe our commitment to socialism to stay alive as long as possible.” In this case, the words of Jim’s unidentified follower are closer to what Newton meant. A true “Revolutionary Suicide” does not decide to take his own life because it will make his decisions easier (as Jim is suggesting that they do in order to avoid having to confront an invasion of soldiers who might be black), but will instead stay alive as long as possible to fight for the cause.

Tape Q833 is not dated, but the current events mentioned on the tape put its recording in March of 1978. In this “White Night,” Jones is both irritated and fearful that the CIA will try to invade or infiltrate Jonestown. He is upset about the legal battles that the Temple is in the midst of, especially the Stoen custody case, as well as Guyana’s refusal to give Jonestown’s physician, Larry Schacht, certification to practice medicine in Jonestown or anywhere else in Guyana. While repeating a consistent mantra that “non-revolutionary suicide is immoral,” Jones also threatens that if they can’t secure their freedom by surviving the current “White Night,” that they should all “take a potion” that would lead to their deaths.

The tape includes a second, more specific definition of “Revolutionary Suicide” as “running right out with a bomb in your hand… running at a car with something strapped to you that had the enemy in it and blowing it and yourself up. That would be Revolutionary Suicide and that would be an honorable thing to do.” However, by Newton’s definition, what Jones is describing as a “Revolutionary Suicide” is actually a Reactionary Suicide. Running up to a car with explosives strapped to oneself and detonating the bomb does not further the revolutionary cause in a manner that Newton was referring to by any means. Instead it is simply killing oneself and taking a member or two of the opposition with you. It is a short term solution, not one that brings about any true, actual change that will be felt in future generations.

The next tape in which Jones clearly mentions “Revolutionary Suicide” is Q757, recorded on April 1, 1978. It is a “White Night” situation, called by Jones because he isn’t feeling well. He wonders what will happen to his movement if he were to die. Jones states, “I believe basically, morally, Revolutionary Suicide’s the only kind of thing that’s justified, and I’m very much concerned that if you commit suicide or try to die in any other way, doing your own selfish thing or whatever, you will come back [as a lower life form]… We can only be hurt from within, going out and doing something like lying….”

With these comments, Jones is affirming that “Revolutionary Suicide” is the only way to go, although he does not actually define what it is. But he does differentiate it from the suicide of one individual, which would be morally reprehensible. They will die as a group at the same time, he says. That makes it “Revolutionary Suicide.”

However, there is nothing in Newton’s definition of “Revolutionary Suicide” suggesting that everything should be done by a group in unison. Instead, Newton’s definition refers more to the individual revolutionary and how he/she should live. In this tape, we also catch a glimpse as to why Jones would want all of his people to die at one time, along with him. He is afraid that if anyone survives to live without Peoples Temple, they will “lie” about what actually occurred in the movement, which would affect the historical impact that their deaths will make.

Jones also wanted the death of Peoples Temple to be a great historical mark for Socialism. Perhaps one of the greatest ironies of the tragedy is that to this day, hardly anyone who knows about the deaths in Jonestown on November 18, 1978, has the slightest clue that they were meant to be in the “name of Socialism.”

In tape Q637, dated April 12, 1978, Jonestown is enduring another “White Night.” The Concerned Relatives oppositional group in the U.S. has just issued a list of grievances against Jim Jones – including allegations that Jones took people to Jonestown without their consent – and the threat represented by the public proclamation is exacerbated by the fact some of his strongest supporters in the Guyanese government happened to be out of the country. “Suicide is unacceptable,” Jones says in this tape, reiterating what he said two weeks earlier. “Except for revolutionary reasons… They’re not going to make mockery of our babies and torture our old people.” Jones is once again trying to sell the notion that “Revolutionary Suicide” is the only way to go, but yet again, he has misappropriated its meaning.

There’s another word here that has a number of definitions in Jonestown: torture. If Jonestown were to be invaded by an outside source, Jones says on this tape – as he does on Q042 – it would be better for them to kill the babies, the seniors, and then themselves in order to avoid the “torture” of any of the three groups (although he singles out the babies and the seniors as being most vulnerable to such a thing). “Torture” could mean many things, depending on Jones’ mood: physical harm, psychological harm, being made to return to the United States and its “Capitalist evil.” But his definition of “Revolutionary Suicide” as ending one’s life in an attempt to avoid torture is far from what Newton anticipated. On the contrary, an individual who believed in Newton’s “Revolutionary Suicide” would do his best to avoid torture, but would not kill himself to do so. On the contrary, he would acknowledge that his actions might lead to torture to the point of death, but this would not stop the true “Revolutionary Suicide” from completing his tasks.

Tape Q592, dated April 13, 1978, was made the next night during another “White Night.” In this case, Jones is concerned about an upcoming radio news conference scheduled between Jonestown and a group of reporters in San Francisco, during which Jonestown members will address the accusations put forth by the Concerned Relatives. In addition, the Social Security checks from the United States aren’t flowing into Jonestown.

Q592 includes discussion of going to Cuba to ask for asylum. Along the way, Jones mentions that their situation leads to “almost a complete conclusion you have to make, that you’d by necessity have to [have] some sort of death” if they can’t go to Cuba. In this case, Jones does not use the phrase “Revolutionary Suicide,” but since the group is in the midst of a “White Night,” and Jones discussed “Revolutionary Suicide” most often during “White Nights” – and he is discussing their deaths – it is only logical to assume that he has coined yet another definition for Newton’s concept. As before, it varies with the original meaning: no one needs to die if the group can’t relocate to a place where they will be safe. This tape also includes requests from some of the individuals in the collective to return to the United States and kill the enemies of the Temple, even as everyone else dies in solidarity.

Tape Q736 records the press conference anticipated in the previous tape. Jim Jones and some of his membership talk are with reporters in San Francisco via radio to address the issues that were raised by the Concerned Relatives regarding the treatment and care of their kin in Jonestown. Various members of Peoples Temple come to the radio room to read statements for their relatives back in the States. The most disturbing statement is by Harriet Sarah Tropp, who serves as the spokesperson for the group. Before the members make their own comments, Harriet reads from an opening statement in which she details the level of commitment that the people of Jonestown have made to their settlement and Jones:

We would like to address ourselves to a point that has been raised, it seems, about some statement, supposedly issued officially by Peoples Temple, but whose authorship we here are unaware of, to the effect that we prefer to resist harassment and persecution, even if it means death. Those who are lying and slandering our work here, it appears, are trying to use this statement against us. We are not surprised. However, it would seem that any person with any integrity or courage would have no trouble understanding such a position… Patrick Henry captured it when he said, simply, Give me liberty, or give me death. If people cannot appreciate the willingness to die if necessary, rather than to compromise the right to exist, free from harassment, and the kind of indignities we have been subjected to, then they will never understand the integrity, honesty, and the bravery of Peoples Temple, nor the depth of commitment of Jones to the principles he has struggled for all of his life.

Although this statement is not a direct quote from Jones, it is more than likely that he approved Harriet’s message as well as the messages of the other Peoples Temple members in this conference. Neither Tropp nor Jones a direct reference to “Revolutionary Suicide,” but Tropp threatens suicide if the group is not allowed to have freedom from harassment and questioning. Compare this to Newton’s concept: in order to support the struggle, the revolutionary acknowledges that what he is doing may lead to harassment and criticism from the opposition, but a true revolutionary will expect this harassment and take it in stride.

Tape 245, taped in October of 1978, less than a month before Ryan’s fateful visit, shows that Jones was beginning to affect how the members of Peoples Temple saw “Revolutionary Suicide,” and how his corruption of Newton’s language was nearly complete. Another “White Night,” this recording is full of statements made by Jonestown residents about how they would be willing to die for Jonestown, and although their reasons are varied, the underlying theme is a willingness – even a desire – to die in order to leave behind an example of what socialism should be. If the people at Jonestown cannot live without the world investigating their practices and their leader, they would rather die.

This tape seems to have been made for the specific purpose of creating a historical record: Jim Jones and his followers make statements to leave behind after their deaths as a testimony to their fight for Socialism. Numerous people say that they hope that their deaths will encourage others, especially other socialists in the world, to continue on with the struggle to create positive change through socialism. The individuals on the tape want their deaths to be inspirational, and they vow that they are ready to die if Jones says that they have to. What is shocking to me about Tape 245 is that Jones is right there with them, refining their statements as they make them, encouraging them to see that their deaths would be something historical. Even in this tape, in which Jones and his membership clearly want to show that they will affect “Revolutionary Suicide” and give their reasons for feeling that way, they don’t capture the concept that Huey P. Newton has proposed. The wish to leave behind an example, an inspiration for future generations of revolutionaries, is indeed part of “Revolutionary Suicide,” but again, there is nothing in Newton’s definition that requires the revolutionary to die, by his or her own hand.

Finally, there is Q042, which is also known as the “death tape” and was recorded on November 18, 1978, just after the tragic shootings of Congressman Leo Ryan and his entourage at Port Kaituma. In the course of this tape, Jones is informed of the news that Ryan is dead, as are several of the people who visited Jonestown with him, and one of the defectors who left with Ryan. Jones tells his people that there is no way out now, that the congressman is dead, that everyone in Jonestown must die.

In Q042 – which like Q245, must be seen as an attempt to create a historical record – Jones gives numerous reasons for, and descriptions of, “Revolutionary Suicide,” and none meets Newton’s definition.

• If they all take “a potion, like they did in ancient Greece,” he says, they will be able to avoid repercussions for the death of the congressman and his aides. But the true “Revolutionary Suicide” doesn’t kill himself/herself to avoid the questions of authorities, and, indeed, the true “Revolutionary Suicide” expects that he/she will have his/her motives and actions questioned.

• “Revolutionary Suicide” is “protesting the conditions of an inhumane world,” a way to avoid the torturing of babies and seniors in the group, and a way to control the manner of their deaths, which Jones states are inevitable.

• With the death of the congressman, there will be even more investigations into Peoples Temple: this is yet another reason to die, in order to prevent the people in Jonestown from having to suffer through the questions of others and more harassment for the group.

• Before Ryan and his entourage left Jonestown for the Port Kaituma airstrip, Jonestown resident Ujara attacked the congressman with a knife; the attack was thwarted by other Temple members who pulled Ujara away, and Ryan was not injured. Jones knows there will be repercussions from the attack, but rather than “hand over Ujara,” Jones reminds his followers – as he has for years – that they are all one and that they would rather die than to allow one individual, even if he has committed a crime, to be taken from the collective. But it is the individual who is the “Revolutionary Suicide,” not a group.

• Jones also states that “the best testimony that we can make is to leave this god-damned world,” and that “we win when we go down.” This is the exact opposite of Newton’s concept of “Revolutionary Suicide,” who believed that a revolutionary fought for his cause even if it led to his death – that’s how the death made a difference – and, even more importantly, that a revolutionary made an impact when he was able to pass on his struggle to another generation. By instigating the deaths of everyone in Jonestown, including the children, Jones has destroyed any chance of the next generation picking up the fight and continuing on.

• Finally, Jones states that the deaths of Peoples Temple are “the will of the sovereign being.” Jones is contradicting both Newton and himself with this statement, since he had long before stated that there was no sovereign being or a God. In the article, “I am we, or Revolutionary Suicide,” Newton states that individuals are sent to the grave by “the unknowable force that dictates to all classes, all territories, all ideologies; he is death, the Big Boss… An ambitious man seeks to dethrone the Big Boss, to free himself, to control when and how he will go to the grave.”

Jones was notorious for believing that he would die in a “blaze of glory” at some point in his life. By November 1978, though, he was a very sick man, and had been so for a number of months. His son, Stephen Jones – who was in Georgetown with the Jonestown basketball team during Ryan’s visit – believes that if the mass suicide had not occurred, Jones would have been dead from his physical ailments within a matter of months. No doubt, Jim knew that his own death was coming, and no doubt, this is part of why he decided that all lives in Jonestown should be extinguished once the opportunity presented itself. He just needed a reason to call for everyone to die, and the attack on Leo Ryan and his entourage was the perfect catalyst.

Was it “Revolutionary Suicide”?

On that final day, as Jim Jones called for “Revolutionary Suicide” over and over again, and 909 people died in Jonestown, were any part of the actions that took place “Revolutionary Suicide” as conceptualized by Huey P. Newton? The answer is a resounding “no.” The actions of attacking Congressman Ryan in Jonestown and at Port Kaituma were not “revolutionary” in any manner. They were desperate attempts by Jones and his followers to protect themselves from what they saw as the “prying eyes” of others. Moreover, even though 14 Jonestown residents left with Ryan, none of the people whom the Concerned Relatives said were being held against their will were among them. Ryan’s report upon his return to the U.S. would have likely disappointed Jones’ critics more than the Temple leader. The congressman had given Jonestown a glowing review the night before. All would have been (more or less) well if it hadn’t been for Ujara’s attack.

Neither can the killings at Port Kaituma be considered revolutionary in nature: again, they were a desperate attempt to keep Ryan from returning to the United States and telling others about what had happened to him, which Jones feared would lead to more congressmen, more “persecution.”

Finally, calling everyone to the pavilion and suggesting that they commit suicide in order to avoid the consequences which would be coming for those deaths is not revolutionary in nature. Rather, as one survivor described it, it was just a senseless waste.

Legacy

What is left behind? The legacies of Jim Jones and of Huey P. Newton couldn’t be more different. Jones is seen as a cult leader, as a mass murderer, a madman, all because of those last few moments in the jungle of Guyana. As I have written before, the stigma of suicide is so great that both the good and the bad of Peoples Temple have been forgotten: because they “committed suicide,” those people who died are viewed as taboo, an anomaly, the “other.”

Huey Newton was shot to death during a drug transaction on August 22, 1989. He had become a victim of one of the greatest scourges of his people, a scourge that he himself had fought against. And yet, Newton is still seen as a hero, as someone who may have lost his way, but who started out with great promise. Why is that?

The biggest reason that Jim Jones and Huey Newton are seen differently undoubtedly comes from how they handled their fame. Jones wanted to be superhuman, and he encouraged his followers to see him as such, which, to many, smacks of a cult leader. Newton, on the other hand, never wanted to be seen as anything other than an ordinary man. As a result, Newton’s legacy is of a man with a great, revolutionary mind, who personally lost his way, but didn’t take others with him, a far cry from the legacy of Jones. Although Jones used Newton’s term “Revolutionary Suicide,” the Temple leader was not able to gain the legitimacy that he wanted by trying to make the terminology his. Jones was better able to persuade his followers, many of whom were African-American, by borrowing the rhetoric of one of the greatest minds of the Black Power movement, but to what end? He didn’t use the words to better enrich the lives of those who followed him, but to cut their lives short and lead them to an early grave.

At its core, “Revolutionary Suicide” is a noble and beautiful concept about fighting for change, fighting to end oppression and to set things right for one’s self and ones’ community. It is a concept that defined the Black Panther Party’s struggle, and the struggle of true revolutionaries everywhere. In the hands of Jim Jones, it was corrupted and maligned until it was no longer what Huey Newton intended it to be. It is my greatest hope that, after having read this article, individuals who listen to the tapes made at Jonestown and who hear Jones discussing or calling for “Revolutionary Suicide” will know just how much Jones perverted the term and tried to twist it to fit his needs and not the needs of his people.

True “Revolutionary Suicide” is still alive today, and both the concept and the author of the idea deserve to have it linked to something greater than the poisoned mind of Jim Jones.

(Bonnie Yates earned her BA in Psychology from Northern Illinois University, and did her undergraduate work in the Northern Illinois University Adolescent Suicidology Lab. A second article in this report appears here. She can be reached here.)