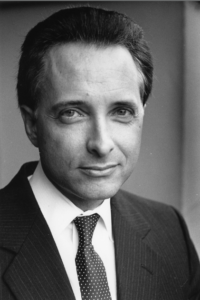

Chris Hatcher was a clinical professor of psychology at University of California, San Francisco. That was his vocation. But his work with Jonestown survivors led him to become more, at least for those in the Peoples Temple community he came in contact with. In the immediate aftermath of November 18, Chris undoubtedly saved the lives of Jonestown survivors, relatives, and others by his compassionate understanding of their losses. In the years that followed – until his death 20 years later – he stood as a quiet presence at memorial services and other events, his kindness and concern palpable.

Chris Hatcher was a clinical professor of psychology at University of California, San Francisco. That was his vocation. But his work with Jonestown survivors led him to become more, at least for those in the Peoples Temple community he came in contact with. In the immediate aftermath of November 18, Chris undoubtedly saved the lives of Jonestown survivors, relatives, and others by his compassionate understanding of their losses. In the years that followed – until his death 20 years later – he stood as a quiet presence at memorial services and other events, his kindness and concern palpable.

Ten days after the Jonestown tragedy, San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and County Supervisor Harvey Milk were assassinated, and Dianne Feinstein became the new mayor. Within a few days of her appointment, she met with a small advisory group that included Chris Hatcher to chart a path forward in addressing the two violent events. In considering what to do about the vestiges of the Temple that remained in the city, according to Hatcher, the group decided that:

(1) direct contact needed to be made quickly with members inside the San Francisco Temple; (2) the potential for self-destructive violence inside the Temple needed assessment; and (3) the potential for violence between Temple groups and relatives needed assessment (Hatcher 1989a: 133).

Hatcher describes the tense encounters he had with surviving members and oppositional relatives at that time. But he also discusses the common ground they were able to reach. An expert in the psychology of trauma, he held frequent meetings with both individuals and groups. He worked with county welfare agents to help find employment for those who had suddenly lost their jobs or had returned to the United States with the stigma of murder and suicide attached.

He was able to navigate the territory between the loyalists, who saw the good work of the Temple in tatters, and the opponents, who feared the survivors. Not surprisingly, he found that those in the defector camp experienced not only grief, but also guilt along with anxiety that Jonestown was not the end of the violence.

For many years we saw Chris at the annual memorial service at Evergreen Cemetery organized by Jynona Norwood. The service was frequently followed by lunch at a local seafood restaurant in Berkeley, where he would generally talk with my parents, John and Barbara Moore. He spoke at the services on a few occasions, but generally he remained in the background—not aloof, but rather not wishing to draw attention to himself.

When we asked him to contribute to a book of essays about the people of Peoples Temple, he insisted on writing two—one about coercion and control that he said he had promised to survivors; the other a look at how people survived the tragedy (Hatcher 1989a and 1989b). The first essay was intended to demonstrate to former members that they had lived in a very controlled environment that limited their choices. The second essay presented a historical overview of governmental responses to Temple survivors in the San Francisco Bay Area. In another volume we edited, he wrote on “Cults, Society and Government,” an analysis of what governments can, and cannot do, in regard to behaviors of religious groups (Hatcher 1989c).

I think I vaguely knew that Chris had worked on other traumatic incidents, but I wasn’t aware of the extent until I read the article about him in Wikipedia—which makes no mention of Jonestown. He assisted relatives of children who had been abducted, such as Marc Klaas. His gentleness stood in marked contrast to his professional expertise as a forensic expert in criminal violence.

We don’t know how many Temple survivors and relatives contacted Chris, but we know quite a few benefited from his comprehension of their situation. He understood their resistance to talking to naïve, and even unforgiving, social workers. He knew better than to push.

My father had a favorite poem, “The Host,” by the Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu, which I think captures the spirit of Chris Hatcher:

Beautiful life, letting anyone attend

Making no distinction between left or right,

Feeding everyone, refusing no one,

Has not provided this bounty to show how much it owns,

Has not fed and clad its guests

With any thought of claim

And, because it lacks the twist

Of mind or body in what it has done,

The guile of head or hands,

Is not always respected by a guest.

Others appreciate welcome from the perfect host

Who barely appearing to exist,

Exists the most.

Works Cited

———. 1989b. “Coercion, Control and Mass Suicide.” In The Need for a Second Look at Jonestown, 61–71.

———. 1989c. “Cults, Society and Government.” In New Religious Movements, Mass Suicide, and Peoples Temple: Scholarly Perspectives on a Tragedy, ed. Rebecca Moore and Fielding M. McGehee III, 179–98. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

Marc Klaas. 1999. “Remembering Dr. Chris Hatcher (1946–1999)”. In Klaas Action Review: The Newsletter of the Marc Klaas Foundation for Children, 2. Sausalito, CA: Klaas Kids Foundation.

(Editor’s note: Rebecca Moore is Professor Emerita of Religious Studies at San Diego State University, and has written and published extensively on Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Rebecca is also the co-manager of this website. Her other articles in this edition of the jonestown report are Dr. Hardat Sukhdeo: The Man Who Knew Too Little, Godwin’s Law and Jones’ Corollary, The Cult of Jim Jones, and Striking to the Marrow of Jonestown. She is also the author of a second remembrance, for longtime Temple scholar Mary Sawyer. Her full collection of articles on this site may be found here. She may be reached at remoore@sdsu.edu.)