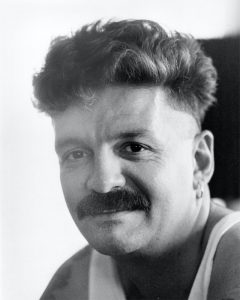

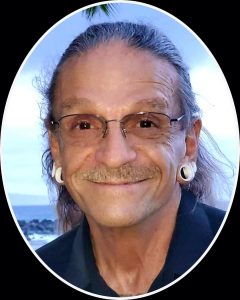

(Vernon Gosney, who left Jonestown with Congressman Leo Ryan on November 18, 1978, and was seriously wounded during the shootings at the Port Kaituma airstrip, died on January 31, 2021, due to complications of heart bypass surgery.)

(Vernon Gosney, who left Jonestown with Congressman Leo Ryan on November 18, 1978, and was seriously wounded during the shootings at the Port Kaituma airstrip, died on January 31, 2021, due to complications of heart bypass surgery.)

I don’t remember the first time that Becky and I met Vernon, but it was undoubtedly at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland for one of the services honoring those who had died in Jonestown. By the time I found myself in regular conversation with him, it seemed like we had been talking for a long time. That isn’t to say they were always easy conversations: we met in the crucible of the deaths in Jonestown – including that of his son – and of his own injuries sustained at the hands of my wife’s brother-in-law at the Port Kaituma airstrip on November 18, 1978. He was never one to hide his light under a bushel, so to speak; you knew pretty much where he stood on the issues which surrounded the tragedy.

Still, I will always remember Vernon as a kind man, someone who didn’t let differences of opinion stand in the way of a relationship. We didn’t see each other that often in the quarter century we knew each other, but we always greeted each other warmly. He also introduced us to his friends, including Alan Swanson, a former member of Peoples Temple who left the group long before it emigrated to Guyana. The strongest memory of that first meeting was their relaxed banter in the presence of Becky and me as to which of my wife’s two sisters – who had also been in the Temple and who died in Jonestown – she favored the most.

Most of our contacts over the years were professional, loosely speaking. As the editor of the Jonestown website, I was always soliciting his writings for our annual publication, and he contributed more than a half dozen pieces over the years. He was also a charter member of the site’s speaker’s bureau, the place that documentarians and reporters, students and scholars, and others who were interested in the Jonestown story could ask him for his perspectives. In later years, he asked me to review the requests before passing them on to him, but I cannot recall a single time that he ended up turning down a sincere inquiry to hear his insights.

The request for me to stand between him and the general public was understandable. Several Jonestown survivors receive venomous and anonymous – those two things go hand-in-hand, of course – emails from people who chose to belittle the survivors’ decision to leave Jonestown under the circumstances they did. Probably none was the target of vitriol more than Vernon, who, in the eyes of these writers, had callously sacrificed his son by leaving him behind even as he saved himself. I don’t know how he handled the ugly notes that reached him, but I know they were numerous.

One of the earlier requests for an interview that I knew about turned into a deeper conversation. In the early 2000s, Michael Bellefountaine received an assignment to write a 700-word piece for a gay publication in San Francisco about the lives of the gay men and women in the Temple. Vernon spoke with him at length, as did several other men, and – with the wealth of information Michael gathered – his project eventually transformed itself into a book. The relationship between Vernon and Michael became fraught over the years – one month, Vernon was writing the forward to the manuscript; the next month, the two men had had a falling-out and Vernon didn’t even want his name in the book – and while the friendship was tested, I recall that it endured at the time of Michael’s own death 15 years ago.

Vernon continued to attend numerous memorial services at Evergreen over the years, and genuinely relished his reconnections with friends with whom he shared sometimes difficult memories. I do remember one service, though, the first that survivors and former members themselves organized on their own, during which everyone was supposed to stand in a circle and speak what was in their hearts. One former member who is a minister in his own right chose to use his time by offering a Christian prayer. Several atheists in the crowd put up with it, but Vernon felt as though the prayer itself was somewhat disrespectful of the gathering, and broke away from the circle, standing several feet away with his back to the group, to express his displeasure. We all got it… except for perhaps the minister.

But my strongest memory of Vernon, and my greatest admiration for him, came in 2001. Larry Layton, the man who shot and seriously wounded Vernon in 1978, had been in prison for most of the intervening years, and various campaigns to release him on parole – and even to secure a presidential pardon from Bill Clinton – had failed. Undeterred, the Layton family and its supporters pressed on for yet another parole hearing, and along the way, collected about a hundred letters of support. They were all advisory, though, playing a supporting role to the lead that Vernon took.

But my strongest memory of Vernon, and my greatest admiration for him, came in 2001. Larry Layton, the man who shot and seriously wounded Vernon in 1978, had been in prison for most of the intervening years, and various campaigns to release him on parole – and even to secure a presidential pardon from Bill Clinton – had failed. Undeterred, the Layton family and its supporters pressed on for yet another parole hearing, and along the way, collected about a hundred letters of support. They were all advisory, though, playing a supporting role to the lead that Vernon took.

The hearing date was set and – even though it took place about a week after the attacks of 9/11, when the whole country was on edge and air travel was challenging due to heightened security – Vernon flew from Hawaii to southern California at his own expense to be there. He made the trip for one purpose and one purpose alone: to speak for the release of the man who had nearly killed him 23 years earlier.

I didn’t attend the hearing, and Vernon didn’t really want to speak of it himself, but another one of Larry’s advocates did accompany Vernon and told us what happened. Appearing in the uniform of the police officer that he was in Hawaii – consciously aware of the gravitas that would give to his remarks – Vernon went against the grain of most victim impact statements and called for Larry to be freed. At the end, and in keeping with the usual practice given to victims, the hearing officer gave Vernon the option to leave the room before further testimony was heard – and to his surprise, Vernon accepted it. The hearing officer was perplexed: hadn’t Vernon just sat in Larry’s corner? Why would he want to leave while others spoke on Larry’s behalf? Vernon replied that he had been upset by the appearance of the man he saw before him, a man who was showing the impact of being in prison for a crime for which he had more than paid the price, and Vernon wanted – he needed – to leave. According to the other advocate in attendance, that departing remark as much as anything else secured Larry’s release.

I’ll miss Vernon. I’ll miss his sometimes mercurial temperament overlaying a deep spirit of generosity. Even though his path was rocky with numerous tragedies throughout his life, his ability to find forgiveness in his heart and his genuine quest for peace, always served as an example that I only wish more of us could embrace.

(Fielding M. McGehee III is the principal researcher for the Jonestown Institute and this website, where he manages tape transcripts, Freedom of Information Act requests, primary source documents, and general inquiries on questions concerning Peoples Temple. His other articles in this edition of the jonestown report are “Drinking the Kool-Aid” as a Tool of Education and A Plea From History. A selection of articles and editorials for the jonestown report is here. He may be reached at fieldingmcgehee@yahoo.com.)