(Connor Ashley Clayton holds an MA in Modern History from from The University of Warwick, and a PhD from Queen Mary University of London. He is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. His other articles in this edition are On Normalising the Study of Peoples Temple, and A Status Check – and A Clarion Call – for Jonestown Researchers. His complete collection of articles for this site is here. He can be reached at connorclayton96@gmail.com.)

Thomas Partak was born in 1946 to James and Alice Marie Partak, in Joliet, Illinois. At some point in the mid-seventies, he joined Peoples Temple, attracted to the group. The attraction was due in part to its stance against the Vietnam War, where he had had at least one tour of duty during his time in the Army. He lived communally in the Temple in San Francisco for a time, until his request to go to the Promised Land was granted. He moved to Jonestown during the rapid migration of the summer 1977, arrriving on August 14. At that point, and for the next 15 months until November 18, 1978, his life was troubled.

Thomas Partak was born in 1946 to James and Alice Marie Partak, in Joliet, Illinois. At some point in the mid-seventies, he joined Peoples Temple, attracted to the group. The attraction was due in part to its stance against the Vietnam War, where he had had at least one tour of duty during his time in the Army. He lived communally in the Temple in San Francisco for a time, until his request to go to the Promised Land was granted. He moved to Jonestown during the rapid migration of the summer 1977, arrriving on August 14. At that point, and for the next 15 months until November 18, 1978, his life was troubled.

As is the case for many other members of Peoples Temple, piecing together the story of Tom Partak’s residency in Jonestown is much like attempting to complete a jigsaw puzzle purchased from a thrift store: the essential components may be there, but pieces are notably missing. What is known, though, is that while Partak was not a part of the community leadership, he became well known to many Jonestown residents in December 1977 as he was brutally disciplined for a litany of crimes: not working hard enough, being an anarchist, wanting to go back to the USA, and eventually, attempting suicide. This suicide attempt has been noted by scholars in the past,[1] yet this article hopes to clarify some of the details surrounding this event, including why the Jonestown leadership made such a rigid example of someone who was very clearly in pain.

Partak’s story – as it can be pieced together across the winter of 77/78 – can tell us a great deal about the internal dynamics at work in Jonestown, including how personal issues could be recast through the lens of the wider crises the Temple was facing at any given moment. Understood within the context of the Temple’s conflicts with their external opponents, the story of Thomas Partak highlights the fragility of Jonestown’s circumstances and how these issues were exacerbated by their wider internal and external contexts.

December 1977

December 1977 was for the Temple a period largely governed by crises. The community seemed focused on re-enacting and reliving aspects of the Six Day Siege which had occurred a few months prior in September. That was when Jonestown residents gathered along the perimeter of the community armed with cutlasses and makeshift weapons in order to defend themselves against an imminent attack which never came. The September crisis was sparked by the arrival of Jeffrey Haas, the attorney representing Tim and Grace Stoen in the John Victor custody dispute. The December crises were similarly motivated when Howard and Beverly Oliver, parents of Bruce and William, arrived in Guyana to find out why they hadn’t heard from their teenage sons for so long. There were additional factors. A month earlier, in mid-November, Jones and the community had dealt with an escape attempt by Thom Bogue and Brian Davis. The community was also grappling with two deaths: the murder of Temple member Chris Lewis back in San Francisco, and the death of Jim Jones’ mother Lynetta in Jonestown, both of which occurred on December 10. Finally, the Temple was still struggling to resolve a conflict with the Social Security Administration and the Postal Service over delivery of SSA checks to beneficiaries in Jonestown, which deprived the community of several thousand dollars each month needed to cover day-to-day expenses. It is within these contexts – external pressures and growing internal instability – that Tom Partak literally and figuratively took centre stage within Jonestown’s purportedly democratic disciplinary events: the Peoples Rallies.

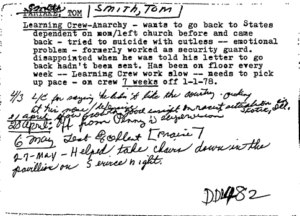

Partak had been on the Learning Crew – Jonestown’s disciplinary labour force – since the middle of November 1977 due to criticisms of his work and attitude, and particularly his desire to return to the United States.[2] By all accounts, Partak worked hard throughout November in the hopes that he would be moved off of the Crew and back to regular work duties. Audiotape Q947-1 recorded during a Peoples Rally on Sunday December 11, 1977 – the day after the death of Lynetta Jones – captured the moment Jim read Partak’s report. Partak’s performance on the Learning Crew had seemed to be satisfactory, up to this point:

Partak had been on the Learning Crew – Jonestown’s disciplinary labour force – since the middle of November 1977 due to criticisms of his work and attitude, and particularly his desire to return to the United States.[2] By all accounts, Partak worked hard throughout November in the hopes that he would be moved off of the Crew and back to regular work duties. Audiotape Q947-1 recorded during a Peoples Rally on Sunday December 11, 1977 – the day after the death of Lynetta Jones – captured the moment Jim read Partak’s report. Partak’s performance on the Learning Crew had seemed to be satisfactory, up to this point:

Tom Partak. Work’s good, but slow. Insistent. Attitude varies. Today’s pace – worked much faster. You keep that up – keep the pace up, and your attitude – won’t be long before you’ll be off. Okay.[3]

Despite Jones’ public affirmation, Partak was unable to adjust to life in Jonestown. He wanted to go home, and his desires became known to Jones and the disciplinary administrators in the community. By December 20, Partak found himself once again in Jones’ gunsights. His confrontation was recorded in the notes for the Peoples Rally held that night, and although a tape of the evening does exist (Q983), the section regarding Partak is notably absent. Recorded in the Peoples Rally notes of December 20:

Partake [Partak], Tom: Still wants to go home. Works poor. He’s been on for 1 month and 1 week. Has been very self-destructive. His living area is dirty, and his clothes. He’s been openly talking about homosexuality… Dad read something Partake had written that was difficult to understand, Partake told Dad when he was counselling with Sharon [Amos] that he liked to do segments.[4]

Also absent from the tape itself, are the Rally notes of some of the harsher aspects of Partak’s confrontation by Jim. Although mild in comparison to what was to come, Jones’ mockery of Partak is evident in the remainder of the notes for December 20:

Dad asked him how does he see himself. He said sad, self-centred, and deranged. Says things come to his brain. Dad said that’s because you’re not tired enough. Dad asked Partake where he was. He said Jonestown. Where’s that. Port Kaituma. Where’s that and Partake said South America. Dad asked him how far from Venezuela he was and what kind of animals were here if you leave this protected area. Tom said crocodiles and boa constrictors, he didn’t know all of them.[5]

The threat of the jungle was a tactic Jones used to dissuade anyone who wanted to leave Jonestown from attempting to escape through the bush: it was home to deadly animals, insects, and plants. Thom Bogue and Brian Davis had attempted to flee Jonestown through the dense jungle a month prior in November, and their confrontation – preserved on audiotape Q933 – contained similar threats about the jungle’s dangers.[6] This did not dissuade Partak, who was determined to make clear his desire to return to the US and his family. The Peoples Rally notes of December 21 include Jones’ response:

Dad told Partake to write a letter and said he could go. Told him when he got back, don’t cry to Dad…[7]

Partak did, in fact, write this letter. Jones, however, would either not read it or at least claim not to have read it. The confrontation regarding this would occur on December 25, 1977: Revolution Day to the Jonestown community, and Christmas Day back home in America. Three sources of information are available to us regarding this specific Peoples Rally and confrontation: the notes written up during and after the event, and two audiotapes which have been long sought-after within Temple scholarship circles. Q948, or the “Let the Night Roar” Tape, has featured in numerous podcasts and documentaries as perhaps one of the most iconic tapes in the Jonestown oeuvre, made infamous by Jonestown’s frenzied ululation and war-cries as Jones calls for them to “let the night roar”. Q938 is an audiotape which appears to take place shortly after Q948, on the same Christmas night Peoples Rally (or, potentially, a day or two after). Q948 and Q938 capture – in detail – the vicious treatment Tom Partak received.

The Peoples Rally notes for December 25 read as follows:

Partake: Still a problem – he thought Dad had sent his letter requesting to go back. He was upset when he found out Dad hadn’t sent his letter. During his confrontation – harshness was applied and Partake answered that he would talk against the cause if he went back. Partake remains on Learning Crew.[8]

The brevity of this note reflects the matter-of-fact way in which records were kept within the Temple, so it doesn’t quite capture the atmosphere present during this session. Q948 and Q938, despite issues in the preservation of audio quality, give us a much clearer image of the “harshness” applied during Partak’s confrontations and bear consideration, especially if the listener places oneself in Partak’s shoes.

The young man’s confrontation begins shortly after Jones’ infamous exhortation to let the night roar. Beginning in Q948, Jones confronts Partak on his desire to return home to his mother:

Jones: Whatcha gonna do when mama dies? What’s the plan, to go back and live with mama? Never leave the old hometown anymore, stay in America all your life. Isn’t that right?

Partak: Uh, uh–

Jones: Oh, don’t lie to me. I didn’t read your goddamn letter, but I know. I know what your plans are.[9]

What can’t be captured within the written word is Jones’ virulent animosity towards Partak, even at the beginning of this engagement, as well as the aggressive participation of the crowd in the Temple’s disciplinary justice. At one point during the tape, Jones threatened what was eventually to come, and was met by applause and cheers from the crowd:

Jones: You’re nervous, aren’t you, man? You don’t know, what, we might pile on you tonight.

Crowd: Cheers, applause.

Jones: … You oughta be glad they ain’t all here though. [Unintelligible name] would whoop your ass.

This disciplinary performance eventually evolved into scenario Jones plays out on stage, wherein he takes the role of a hypothetical FBI agent who would grill Partak upon his return to the States – a process which Jones believes would result in Partak turning against Jonestown and the cause. This must be understood within the context of the conflict between the Temple and its former members who had either joined or aligned themselves with the Concerned Relatives. Jones was obsessed with the possibility of defectors who would go back to the United States and “tell on” Peoples Temple. Jones couldn’t have known whether Partak would participate in this upon his return. The treatment Partak received, however, made this possibility far, far more likely – if he were allowed to return.

It is worth emphasizing that on both Q948 and Q938, a third actor is present – the crowd – and this can be heard clearly on the tapes. At varying points when Partak stumbles over his words, the crowd joins Jones in mocking him. Unknown people from the community hurl insults at him and heckle his attempts to respond, and for the most part, Partak stumbles and swallows his words. One unidentified woman close to the microphone – it has likely been passed to her – chastises him mercilessly:

Unidentified woman: Why? … What the fuck’s wrong with you, man? What’s wrong with you? Why can’t you live with us? I’m asking you another damn thing, before you leave your ass out here, pay for your damn board, you hear? And pay for your board now, you hear? Now, ‘cause I [unintelligible], I’ll whip your ass myself.

Jones: [Laughter].

Unidentified woman: Goddamn– you a goddamn bonehead if you want to be white and right – and you’re white and wrong, goddamn it.

Tom Partak makes a mistake here, which an unidentified man brings to the attention of the assemblage: Partak has laughed at this. What has initially been merely a tense situation now escalates rapidly. Based on the shocked noises from the crowd, and Jones’ exclamation of “Oh, Jesus!” it seems that Partak is physically assaulted by one or more people from the crowd, with the sounds of the blows captured on tape. Jones then resumes the FBI roleplay, and far more aggressively. Jones, and others, repeat the question to Partak – “You like Peoples Temple?” – over and over, as the young man grunts under the sounds of physical altercation. The tape ends without apparent resolution of this conflict, as the track switches to something unrelated entirely.

Q938 continues at some point after the events of Q948. Whilst it was likely recorded later into Christmas Night, in the early hours of December 26, it could also be from a day or two after. The confrontation on this tape – which is absent from Q948 – is centred around the fact that Tom Partak had attempted to commit suicide with a cutlass. Although the timeline is murky, I believe that the events of Q948 directly motivated Partak’s suicide attempt – whether it be the same night or days after. It is clear that Partak’s attempt shook Jones personally – and Jones makes every effort once again to make an example out of Partak in front of the entire community.

So you have a thought you want to go back to the States? It makes you commit suicide? I have thoughts I want to die every second. That wouldn’t make me commit suicide. I wouldn’t hurt a soul, I wouldn’t do that to a soul, not a soul. You don’t want to hurt people. What do you want to hurt people for?[10]

More back and forth is offered. Jones questions whether or not Partak likes pain, and states that suicide by cutlass was obviously going to cause him pain. Partak’s heart-wrenching reply is as follows:

Well, I thought I’d just– Well, that the– shorter than the pain I’m going through every day, I’d just – the mental pain.

Jones takes particular exception to Partak’s alleged selfishness regarding this act. Working himself into a frenzy, he eventually suggests that Partak should be shot through the hip – a suggestion the crowd echoes and supports enthusiastically. This confrontation only devolves further into violence, as Jones himself begins to physically attack Partak:

Jones: You want to leave tonight? Would you like to go tonight? How would you like to leave tonight? Just say you would like to. We got a path we’ll send you through. Any path you wanna take? Do you want to leave tonight?!

Partak: No–

Jones: Miserable goddamned person, look at these people that you’re draining dry, if you don’t have any compassion on me, I’ve lost my mother, God damn you!

The sound of Jones’ laboured breathing through gritted teeth as he beats Partak is echoed as other congregants too participate in the physical beating. Partak attempts to bring hostilities to an end by providing what he believed to be a correct answer, as the situation demanded:

Partak: I’ll change and [unintelligible] I have a socialist consciousness.

Jones: Why you gonna have a socialist consciousness?

Partak: So I can help, uh–

Jones: Because you’re scared to death.

Voices in crowd: That’s right!

Amongst the physical beatings, individuals within the crowd once again take the opportunity to lambast Partak, for wasting Jones’ time, for being white, for being selfish, and for being an elitist. After a flurry of physical punishment, the confrontation is almost over as soon as it began. Partak explains to Jim he will try and work harder, and as the conversation moves forward Jones curtly dismisses him. Thus, Tom Partak’s attempted suicide by cutlass has ended with a visceral public beating not only by members of the congregation, but by Jones himself – a peculiarity, considering in most other confrontations, Jones let others dirty their hands while he remained above the fray.

It is likely that Jim’s response to Partak – and the community’s response in kind – was worsened by the deteriorating situation the Temple was rapidly finding itself in. The deaths of Lynetta Jones and Chris Lewis, the attempted escape of Thom Bogue and Brian Davis, the arrival of the Olivers, the withholding of the Temple’s Social Security cheques, and the increasing pressures from defectors and the broader coalition of Concerned Relatives recast Partak’s personal issues within a broader set of circumstances.

Partak’s attempted suicide wasn’t only a personal decision, in Jones’ eye, it was a condemnation of the entire apparatus Jonestown was built on. As Jones believed traitors and potential defectors lurked within the community, galvanised by the increasing pressures of the Temple’s external opponents, Partak’s actions became not the symptoms of a depressed individual: they were tantamount to anarchy and treason.

1978.

The documentary record of Tom Partak’s final year remains spotty. Mentioned in Edith Roller’s Journals between March and April of 1978, it is clear that Partak was still struggling with life in Jonestown. An entry for a Peoples Rally of 4 March 1978, reads “Tom Partak doesn’t like the country. He was late for work, is defensive, is lapsing into bad habits. Put on Learning Crew.”[11] Roller’s entry for the next Peoples Rally, 10 March, reveals the resurgence of Partak’s depression:

Rally – Tom Partak. Depressed. Nostalgic for San Francisco…. Jim asks him if he wants to be dead. “Sometimes,” he says. “Tonight?” “No, not tonight.” Jim ordered strict security on him.[12]

Three entries for April – 6, 10, and 22 – suggest that things may have changed for Partak, to a degree. “Tom Partak gets extra candy. Better attitude,” reads the first entry.[13] “Jim said Tom Partak wanted to change his name to Tom Smith and he now wanted to stay here,” reads the entry written a few days later.[14] The entry for April 22 is even more surprising: “Partak talked about castrating our children. Thanked Jim for bringing us over.”[15] Temple members often took new names to signify their commitment to the cause and their rebirth as a new individual, and talk of castrating children – although the context is unclear – was likely understood as a his demonstration of new-found commitment. Partak, it seems, was slowly learning to “play the game”. If he wanted to leave Jonestown, he had to be trusted. This was a trust which likely would have never developed.

At some point months after Partak’s confrontations, it seems he wrote a short letter to Jim Jones:

At one time a couple months ago you asked me if I could be trusted to go back to the States do a mission and I said honestly “probably not” because I thought I might get off the plane and head for Illinois & my family, but since my Mom has passed away I don’t have that desire much anymore and I feel I could be trusted to do the job. Other people who really love Jonestown should stay here and build it up and let me go back. I know you can think up a good plan of action and I believe I could carry it out. Respectfully, Tom Partak.[16]

To properly understand this letter, one must understand that Alice Marie Partak – Tom Partak’s mother – did not pass away until 2009.[17] Thus, it is clear that Jones – and likely many others – were involved in deceiving Partak about the death of his mother in order to try and quash his desire to return home. Partak’s letter, however, demonstrates how he himself was still trying to leverage this information in a way that would not only appease Jim, but also open the possibility of his return to America. The facts surrounding the final months of Partak’s life are made much more poignant in that a letter from Alice Marie also survives in the Temple’s documentary record, dated June 6, 1978. The letter reads, in part, as follows:

Dear Tom, we are having beautiful weather here… But enough about us. How are you doing? It is so long since we’ve received a letter that we are naturally quite concerned. Especially since you promised to write: I even called Mattie and she said she hadn’t heard either. Did you get my envelope with the sports news? … I’m enclosing a $5- bill. Buy something for yourself. But, please let us hear from you. If I don’t hear soon I will probably write to Jim Jones. Mattie says he is there too. Love, Mum + all.[18]

The documentary record, unfortunately, ends there, although other documents as yet undiscovered may survive still.

Tom Partak died with everyone else in Jonestown on November 18, 1978. Whether he voluntarily committed suicide – as he allegedly and unsuccessfully attempted a year earlier – or whether he was forced, we may never know. We do know, however, that Partak was an individual who, like many others, loved his mother and his family dearly. This love cost him his freedom within Jonestown, and he likely died believing that his mother had died before him. As for Alice Marie, she likely died not knowing the extent of her son’s troubles in Jonestown, or that her letters to him were not received.

Tom Partak died with everyone else in Jonestown on November 18, 1978. Whether he voluntarily committed suicide – as he allegedly and unsuccessfully attempted a year earlier – or whether he was forced, we may never know. We do know, however, that Partak was an individual who, like many others, loved his mother and his family dearly. This love cost him his freedom within Jonestown, and he likely died believing that his mother had died before him. As for Alice Marie, she likely died not knowing the extent of her son’s troubles in Jonestown, or that her letters to him were not received.

Partak’s remains were identified at Dover Air Force Base in December 1978 and transported to Joliet, Illinois, where his family buried him. One can’t help but feel that in death, Partak’s wish to be with his family was finally fulfilled.

Epilogue.

Partak’s story tells us a lot about how individual experiences, desires, frailties, and hopes could be lost in the maelstrom of hysteria which swept through the Jonestown community periodically, culminating on November 18, 1978. A desire to return home – to see one’s family – was interpreted as disloyalty, anarchy, elitism, and a threat to the very integrity of the community residing in Jonestown. There is a sense of sad irony in that the treatment Partak received for wanting to go home worked in a circular fashion to ensure his wish would not be granted: with all the bad press the Temple was receiving, the beating of a suicidal individual would have made for extremely poor optics. Jones and the Jonestown community leadership were aware of this, and they were particularly aware of how their internal practices looked to the outside world. This was addressed in a broader sense in a Memo from Dick Tropp to Jones, dated May, 1978, in which he asked:

Do we create situations by our procedures and practices that make us vulnerable? The more ‘secretive’ we need to be, the more vulnerable we are to ‘defectors.’[19]

Whether Partak had truly been a vulnerability to the community in November 1977 is unknown. Only Partak knew if he would speak against the Temple upon his return – despite what he may have said in the volatile environment of a Peoples Rally. But the Temple’s disciplinary procedures – which could, and did, on occasion devolve into violent episodes of mob justice – ensured that Partak was an even higher-risk in the Temple’s eyes in a paradoxical fashion. Herein lies the problem of using fear as a motivator: it cannot guarantee the sort of change it expects. Partak’s story seems testament to that fact. And as the Temple’s situation deteriorated rapidly throughout 1978, fear became an increasingly prominent aspect of Jonestown’s restorative and preventative justice system.

The primary sources which survive Jonestown provide an unparalleled glimpse into the lives of the individuals who participated, lived, and worked within the Temple at varying points throughout its history. It is simultaneously one of the richest source bases for microsocial study available; and yet it is peppered with gaps. We may not know everything about Tom Partak – but we know enough from what has survived over the years to be able to confidently tell his story. With hundreds of audiotapes, thousands of documents, and a range of fantastic secondary scholarship at the disposal of Temple scholars today, I can’t help but wonder who else’s story we might be able to tell, provided we have enough fine-tooth combs and perseverance.

Notes:

[1] One example is in Julia Scheeres, A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Hope, Deception, and Survival in Jonestown (Free Press, 2011), p. 123.

[2] Tom Smith [Partak] Personality Card, RYMUR 89-4286-DD-482, available at The Jonestown Institute: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/DD.pdf The card notes a Learning Crew duration of seven weeks, off 1-1-78. Partak was likely put on the Crew around November 13, 1977.

[3] FBI Audiotape Q947-1 (Side B), transcript available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=122774

[4] Notes from Peoples Rally, December 20, 1977, RYMUR 89-4286, C-11-d-14-a – C-11-d-14i, available at The Jonestown Institute: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/PeoplesRallies2.pdf

[5] Notes from Peoples Rally, December 20, 1977.

[6] FBI Audiotape Q933, available at: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27619

[7] Notes from Peoples Rally, December 21, 1977, RYMUR 89-4286, C-11-d-11a – C11-d-11e, available at The Jonestown Institute: http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/PeoplesRallies4.pdf

[8] Notes from Peoples Rally, December 25, 1977, RYMUR 89-4286, C-11-d-12, available at The Jonestown Institute: http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/PeoplesRallies3.pdf

[9] Transcript of Q948, available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=118318

[10] Transcript of FBI Audiotape Q938, available at: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=118321

[11] Edith Roller Journals, 4 March 1978, The Jonestown Institute, available at: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35694

[12] Edith Roller Journals, 10 March 1978, The Jonestown Institute, available at: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35694

[13] Edith Roller Journals, 6 April, 1978, The Jonestown Institute, available at: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35695

[14] Edith Roller Journals, 10 April, 1978, The Jonestown Institute, available at: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35695

[15] Edith Roller Journals, 22 April, 1978, The Jonestown Institute, available at: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35695

[16] Letters to Dad (Part 1), RYMUR 89-4286-N-1-A, 3a-3b, The Jonestown Institute, available at: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/1-ff-enemies.pdf

[17] The obituary entry for Alice Marie Partak can be found at: https://www.geni.com/people/Alice-Partak/6000000020269540828

[18] Letter to Tom from Mom & All, RYMUR 89-4286, EE-1-p-39, a-c, The Jonestown Institute, available at: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/EE1-N-Z.pdf

[19] Memo from Dick Tropp, May 1978, RYMUR 89-4286-EE-1-T-64 – EE-1-T-65, The Jonestown Institute, available at: http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/04-DTropp5-11WhiteNite.pdf